Section 20.3: Cellular Defenses - Agranulocytes

- Page ID

- 146406

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Agranulocytes

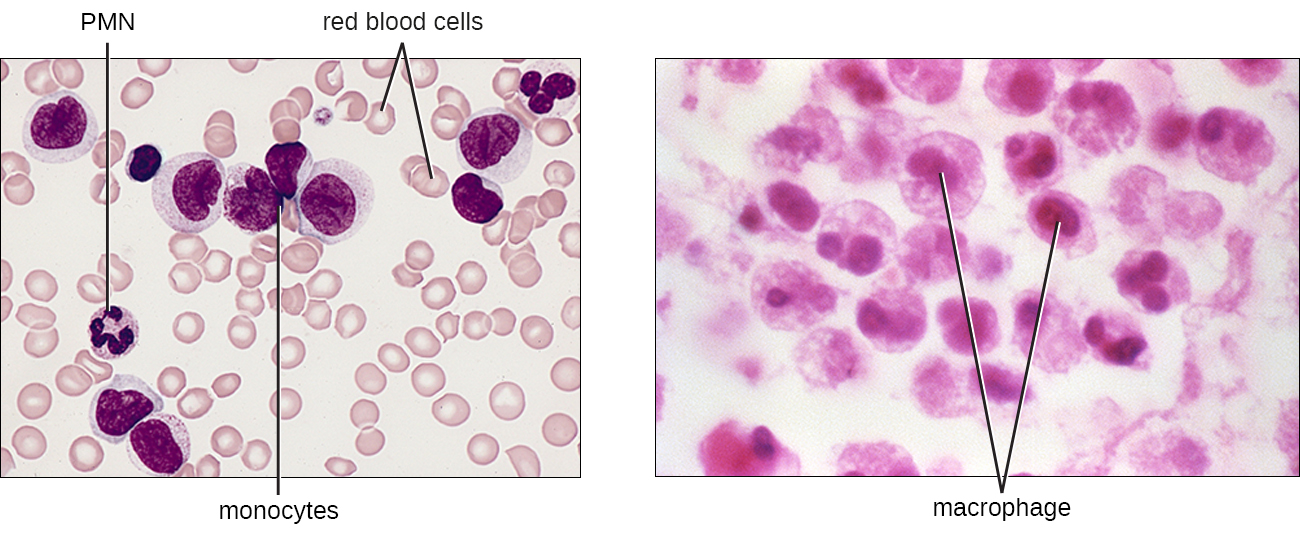

As their name suggests, agranulocytes lack visible granules in the cytoplasm. Agranulocytes can be categorized as lymphocytes or monocytes (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Among the lymphocytes are natural killer cells, which play an important role in nonspecific innate immune defenses. Lymphocytes also include the B cells and T cells, which are discussed in the next chapter because they are central players in the specific adaptive immune defenses. The monocytes differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells, which are collectively referred to as the mononuclear phagocyte system.

Natural Killer Cells

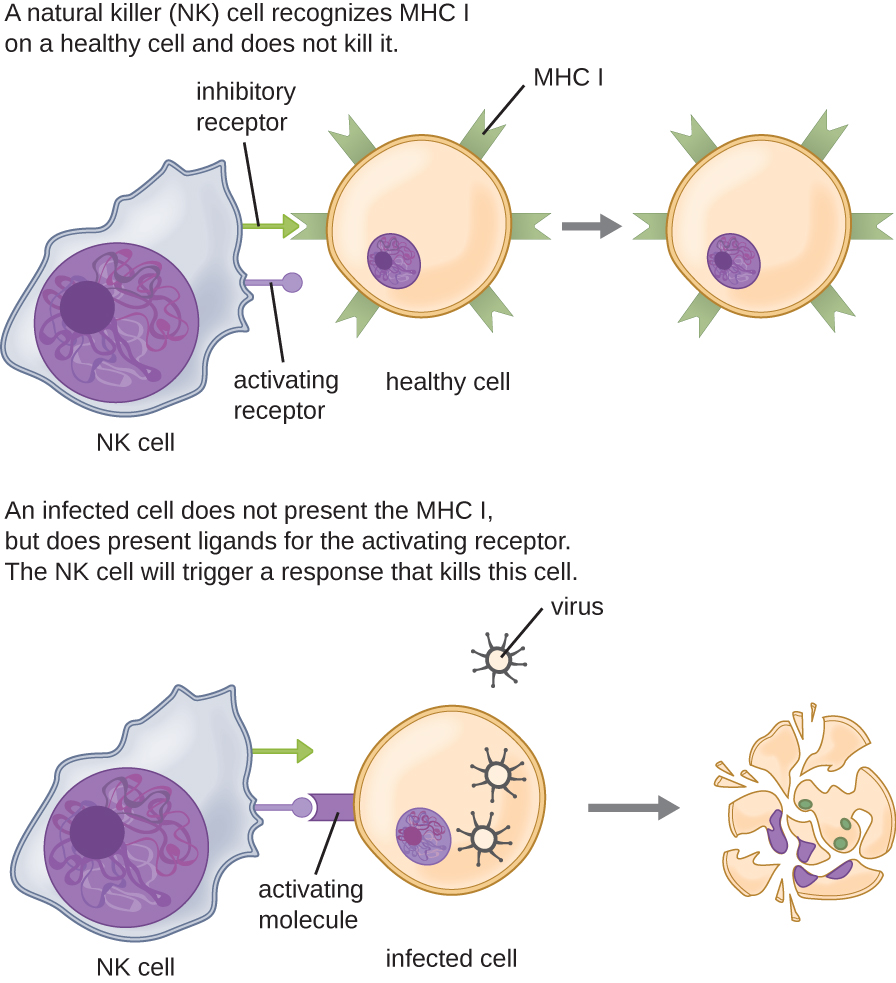

Most lymphocytes are primarily involved in the specific adaptive immune response, and thus will be discussed in the following chapter. An exception is the natural killer cells (NK cells); these mononuclear lymphocytes use nonspecific mechanisms to recognize and destroy cells that are abnormal in some way. Cancer cells and cells infected with viruses are two examples of cellular abnormalities that are targeted by NK cells. Recognition of such cells involves a complex process of identifying inhibitory and activating molecular markers on the surface of the target cell. Molecular markers that make up the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are expressed by healthy cells as an indication of “self.” This will be covered in more detail in next chapter. NK cells are able to recognize normal MHC markers on the surface of healthy cells, and these MHC markers serve as an inhibitory signal preventing NK cell activation. However, cancer cells and virus-infected cells actively diminish or eliminate expression of MHC markers on their surface. When these MHC markers are diminished or absent, the NK cell interprets this as an abnormality and a cell in distress. This is one part of the NK cell activation process (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). NK cells are also activated by binding to activating molecular molecules on the target cell. These activating molecular molecules include “altered self” or “nonself” molecules. When a NK cell recognizes a decrease in inhibitory normal MHC molecules and an increase in activating molecules on the surface of a cell, the NK cell will be activated to eliminate the cell in distress.

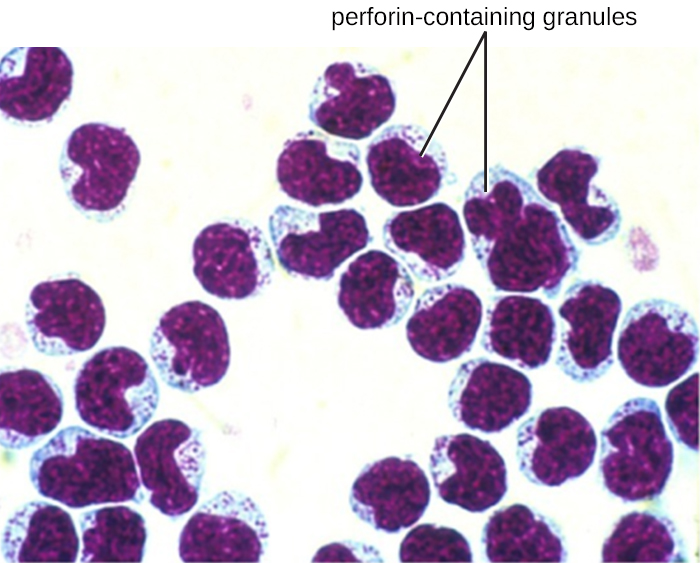

Once a cell has been recognized as a target, the NK cell can use several different mechanisms to kill its target. For example, it may express cytotoxic membrane proteins and cytokines that stimulate the target cell to undergo apoptosis, or controlled cell suicide. NK cells may also use perforin-mediated cytotoxicity to induce apoptosis in target cells. This mechanism relies on two toxins released from granules in the cytoplasm of the NK cell: perforin, a protein that creates pores in the target cell, and granzymes, proteases that enter through the pores into the target cell’s cytoplasm, where they trigger a cascade of protein activation that leads to apoptosis. The NK cell binds to the abnormal target cell, releases its destructive payload, and detaches from the target cell. While the target cell undergoes apoptosis, the NK cell synthesizes more perforin and proteases to use on its next target.

NK cells contain these toxic compounds in granules in their cytoplasm. When stained, the granules are azurophilic and can be visualized under a light microscope (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Even though they have granules, NK cells are not considered granulocytes because their granules are far less numerous than those found in true granulocytes. Furthermore, NK cells have a different lineage than granulocytes, arising from lymphoid rather than myeloid stem cells (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Monocytes

The largest of the white blood cells, monocytes have a nucleus that lacks lobes, and they also lack granules in the cytoplasm (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Nevertheless, they are effective phagocytes, engulfing pathogens and apoptotic cells to help fight infection.

When monocytes leave the bloodstream and enter a specific body tissue, they differentiate into tissue-specific phagocytes called macrophages and dendritic cells. They are particularly important residents of lymphoid tissue, as well as nonlymphoid sites and organs. Macrophages and dendritic cells can reside in body tissues for significant lengths of time. Macrophages in specific body tissues develop characteristics suited to the particular tissue. Not only do they provide immune protection for the tissue in which they reside but they also support normal function of their neighboring tissue cells through the production of cytokines. Macrophages are given tissue-specific names, and a few examples of tissue-specific macrophages are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). Dendritic cells are important sentinels residing in the skin and mucous membranes, which are portals of entry for many pathogens. Monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells are all highly phagocytic and important promoters of the immune response through their production and release of cytokines. These cells provide an essential bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses, as discussed in the next section as well as the next chapter.

| Tissue | Macrophage |

|---|---|

| Brain and central nervous system | Microglial cells |

| Liver | Kupffer cells |

| Lungs | Alveolar macrophages (dust cells) |

| Peritoneal cavity | Peritoneal macrophages |

- Describe the signals that activate natural killer cells.

- What is the difference between monocytes and macrophages?

Key Concepts and Summary

- The formed elements of the blood include red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (leukocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes). Of these, leukocytes are primarily involved in the immune response.

- All formed elements originate in the bone marrow as stem cells (HSCs) that differentiate through hematopoiesis.

- Granulocytes are leukocytes characterized by a lobed nucleus and granules in the cytoplasm. These include neutrophils (PMNs), eosinophils, and basophils.

- Neutrophils are the leukocytes found in the largest numbers in the bloodstream and they primarily fight bacterial infections.

- Eosinophils target parasitic infections. Eosinophils and basophils are involved in allergic reactions. Both release histamine and other proinflammatory compounds from their granules upon stimulation.

- Mast cells function similarly to basophils but can be found in tissues outside the bloodstream.

- Natural killer (NK) cells are lymphocytes that recognize and kill abnormal or infected cells by releasing proteins that trigger apoptosis.

- Monocytes are large, mononuclear leukocytes that circulate in the bloodstream. They may leave the bloodstream and take up residence in body tissues, where they differentiate and become tissue-specific macrophages and dendritic cells.