Section 20.2: Cellular Defenses - Granulocytes

- Page ID

- 146405

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Granulocytes

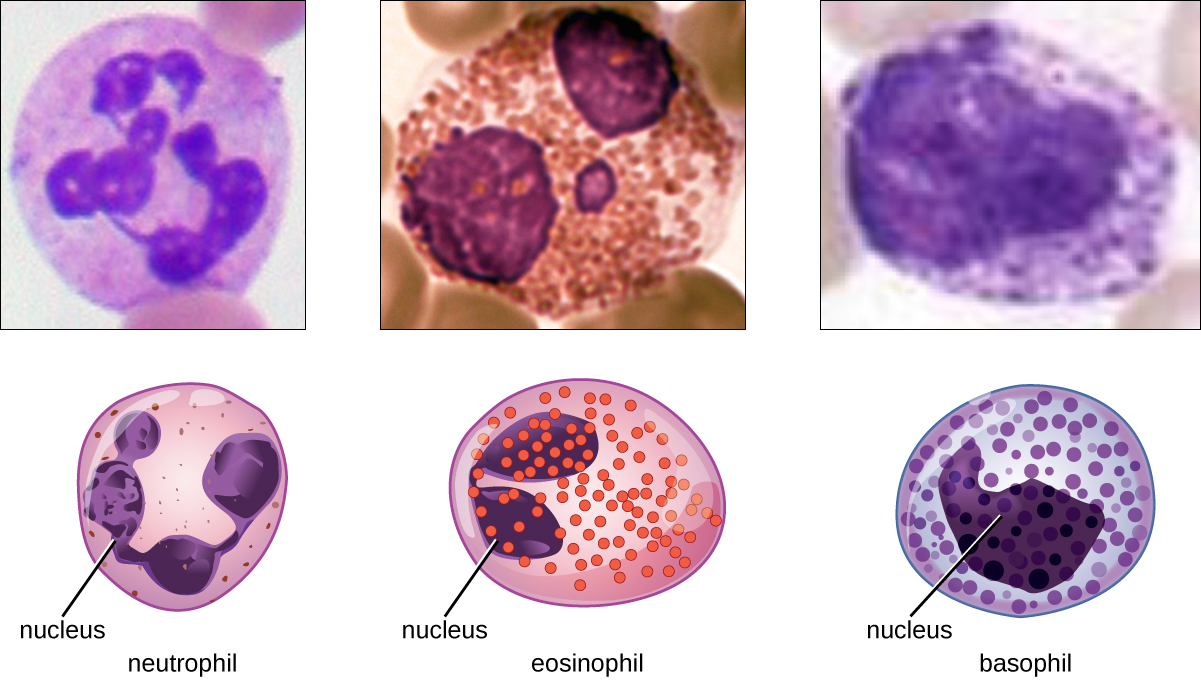

The various types of granulocytes can be distinguished from one another in a blood smear by the appearance of their nuclei and the contents of their granules, which confer different traits, functions, and staining properties. The neutrophils, also called polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), have a nucleus with three to five lobes and small, numerous, lilac-colored granules. Each lobe of the nucleus is connected by a thin strand of material to the other lobes. The eosinophils have fewer lobes in the nucleus (typically 2–3) and larger granules that stain reddish-orange. The basophils have a two-lobed nucleus and large granules that stain dark blue or purple (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Neutrophils (PMNs)

Neutrophils (PMNs) are frequently involved in the elimination and destruction of extracellular bacteria. They are capable of migrating through the walls of blood vessels to areas of bacterial infection and tissue damage, where they seek out and kill infectious bacteria. PMN granules contain a variety of defensins and hydrolytic enzymes that help them destroy bacteria through phagocytosis (described in more detail in Pathogen Recognition and Phagocytosis) In addition, when many neutrophils are brought into an infected area, they can be stimulated to release toxic molecules into the surrounding tissue to better clear infectious agents. This is called degranulation.

Another mechanism used by neutrophils is neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are extruded meshes of chromatin that are closely associated with antimicrobial granule proteins and components. Chromatin is DNA with associated proteins (usually histone proteins, around which DNA wraps for organization and packing within a cell). By creating and releasing a mesh or lattice-like structure of chromatin that is coupled with antimicrobial proteins, the neutrophils can mount a highly concentrated and efficient attack against nearby pathogens. Proteins frequently associated with NETs include lactoferrin, gelatinase, cathepsin G, and myeloperoxidase. Each has a different means of promoting antimicrobial activity, helping neutrophils eliminate pathogens. The toxic proteins in NETs may kill some of the body’s own cells along with invading pathogens. However, this collateral damage can be repaired after the danger of the infection has been eliminated.

As neutrophils fight an infection, a visible accumulation of leukocytes, cellular debris, and bacteria at the site of infection can be observed. This buildup is what we call pus (also known as purulent or suppurative discharge or drainage). The presence of pus is a sign that the immune defenses have been activated against an infection; historically, some physicians believed that inducing pus formation could actually promote the healing of wounds. The practice of promoting “laudable pus” (by, for instance, wrapping a wound in greasy wool soaked in wine) dates back to the ancient physician Galen in the 2nd century AD, and was practiced in variant forms until the 17th century (though it was not universally accepted). Today, this method is no longer practiced because we now know that it is not effective. Although a small amount of pus formation can indicate a strong immune response, artificially inducing pus formation does not promote recovery.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils are granulocytes that protect against protozoa and helminths; they also play a role in allergic reactions. The granules of eosinophils, which readily absorb the acidic reddish dye eosin, contain histamine, degradative enzymes, and a compound known as major basic protein (MBP) (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). MBP binds to the surface carbohydrates of parasites, and this binding is associated with disruption of the cell membrane and membrane permeability.

Basophils

Basophils have cytoplasmic granules of varied size and are named for their granules’ ability to absorb the basic dye methylene blue (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Their stimulation and degranulation can result from multiple triggering events. Activated complement fragments C3a and C5a, produced in the activation cascades of complement proteins, act as anaphylatoxins by inducing degranulation of basophils and inflammatory responses. This cell type is important in allergic reactions and other responses that involve inflammation. One of the most abundant components of basophil granules is histamine, which is released along with other chemical factors when the basophil is stimulated. These chemicals can be chemotactic and can help to open the gaps between cells in the blood vessels. Other mechanisms for basophil triggering require the assistance of antibodies, as discussed in B Lymphocytes and Humoral Immunity.

Mast Cells

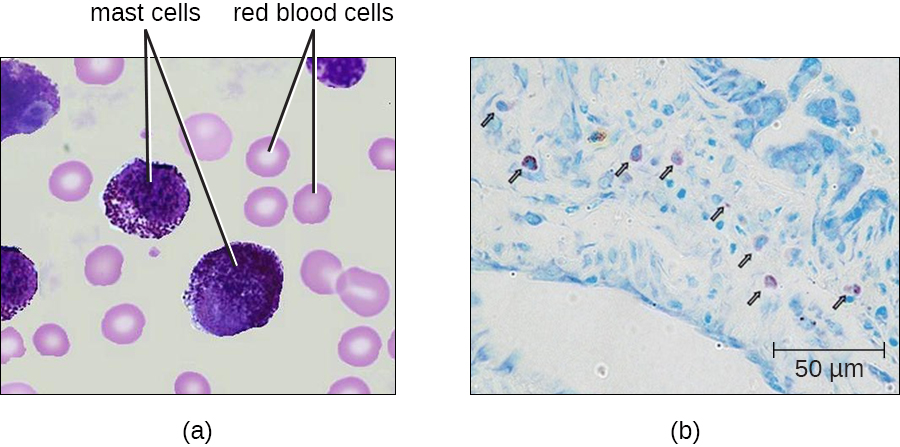

Hematopoiesis also gives rise to mast cells, which appear to be derived from the same common myeloid progenitor cell as neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils. Functionally, mast cells are very similar to basophils, containing many of the same components in their granules (e.g., histamine) and playing a similar role in allergic responses and other inflammatory reactions. However, unlike basophils, mast cells leave the circulating blood and are most frequently found residing in tissues. They are often associated with blood vessels and nerves or found close to surfaces that interface with the external environment, such as the skin and mucous membranes in various regions of the body (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

- Describe the granules and nuclei of neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, and mast cells.

- Name three antimicrobial mechanisms of neutrophils

Key Concepts and Summary

- The formed elements of the blood include red blood cells (erythrocytes), white blood cells (leukocytes), and platelets (thrombocytes). Of these, leukocytes are primarily involved in the immune response.

- All formed elements originate in the bone marrow as stem cells (HSCs) that differentiate through hematopoiesis.

- Granulocytes are leukocytes characterized by a lobed nucleus and granules in the cytoplasm. These include neutrophils (PMNs), eosinophils, and basophils.

- Neutrophils are the leukocytes found in the largest numbers in the bloodstream and they primarily fight bacterial infections.

- Eosinophils target parasitic infections. Eosinophils and basophils are involved in allergic reactions. Both release histamine and other proinflammatory compounds from their granules upon stimulation.

- Mast cells function similarly to basophils but can be found in tissues outside the bloodstream.

- Natural killer (NK) cells are lymphocytes that recognize and kill abnormal or infected cells by releasing proteins that trigger apoptosis.

- Monocytes are large, mononuclear leukocytes that circulate in the bloodstream. They may leave the bloodstream and take up residence in body tissues, where they differentiate and become tissue-specific macrophages and dendritic cells.