5.1: Nucleus and the Endomembrane System

- Page ID

- 160836

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Explain the distinguishing characteristics of eukaryotic cells

- Describe internal and external structures of prokaryotic cells in terms of their physical structure, chemical structure, and function

- Identify and describe structures and organelles unique to eukaryotic cells

- Compare and contrast similar structures found in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells

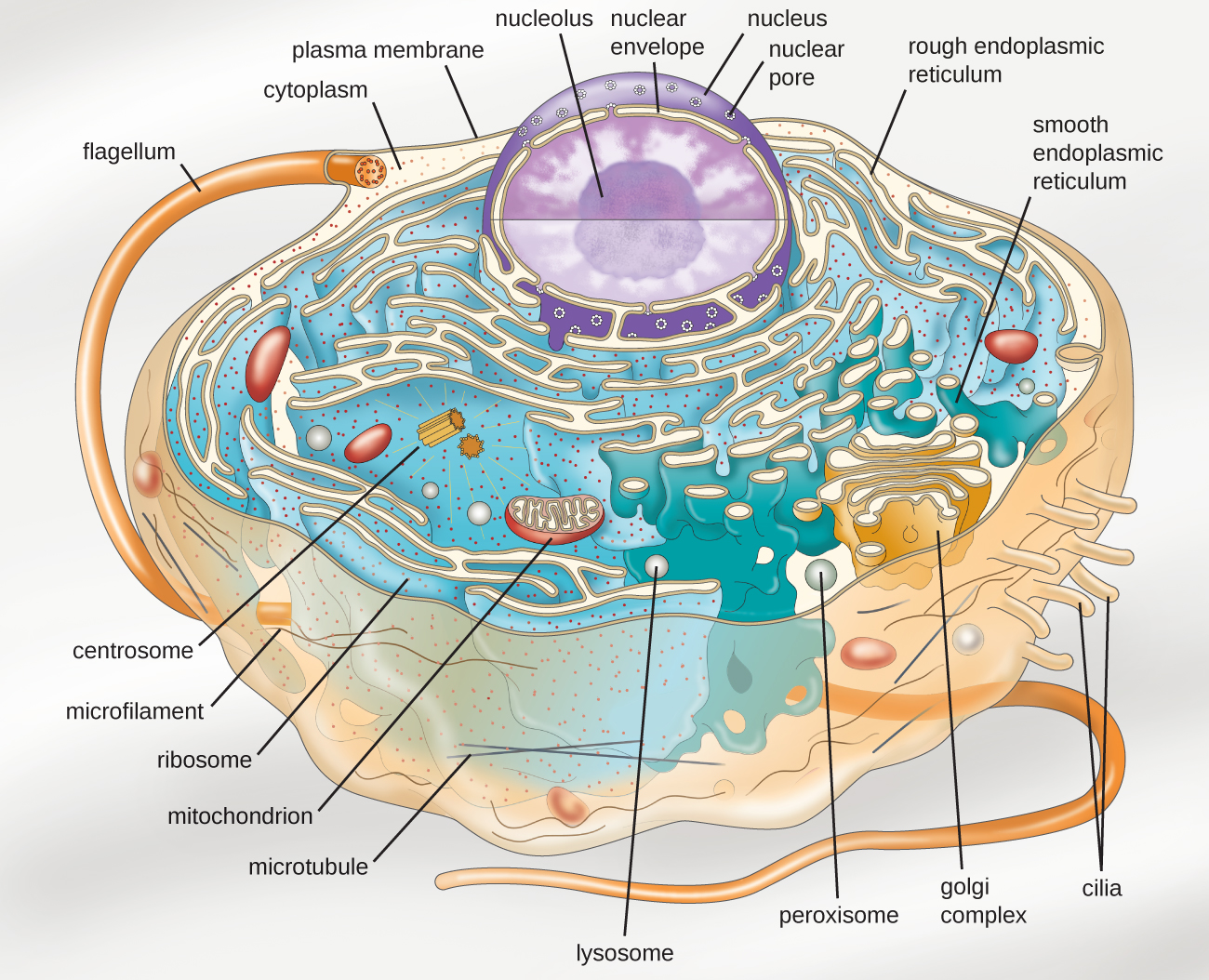

Eukaryotic organisms include protozoans, algae, fungi, plants, and animals. Some eukaryotic cells are independent, single-celled microorganisms, whereas others are part of multicellular organisms. The cells of eukaryotic organisms have several distinguishing characteristics. Above all, eukaryotic cells are defined by the presence of a nucleus surrounded by a complex nuclear membrane. Also, eukaryotic cells are characterized by the presence of membrane-bound organelles in the cytoplasm. Organelles such as mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes are held in place by the cytoskeleton, an internal network that supports transport of intracellular components and helps maintain cell shape (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The genome of eukaryotic cells is packaged in multiple, rod-shaped chromosomes as opposed to the single, circular-shaped chromosome that characterizes most prokaryotic cells. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) compares the characteristics of eukaryotic cell structures with those of bacteria and archaea.

| Cell Structure | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Archaea | ||

| Size | ~0.5–1 μM | ~0.5–1 μM | ~5–20 μM |

| Surface area-to-volume ratio | High | High | Low |

| Nucleus | No | No | Yes |

| Genome characteristics |

|

|

|

| Cell division | Binary fission | Binary fission | Mitosis, meiosis |

| Membrane lipid composition |

|

|

|

| Cell wall composition |

|

|

|

| Motility structures | Rigid spiral flagella composed of flagellin | Rigid spiral flagella composed of archaeal flagellins | Flexible flagella and cilia composed of microtubules |

| Membrane-bound organelles | No | No | Yes |

| Endomembrane system | No | No | Yes (ER, Golgi, lysosomes) |

| Ribosomes | 70S | 70S |

|

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Cell Morphologies

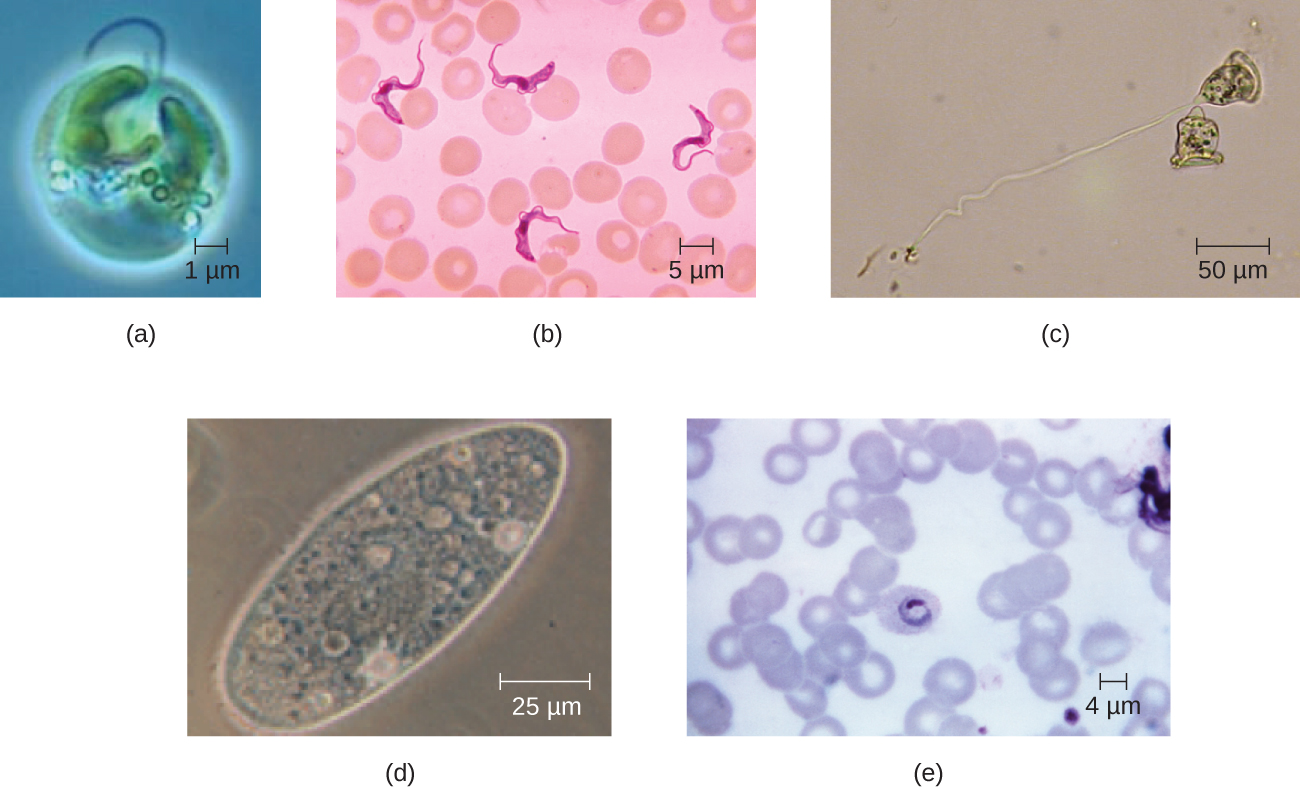

Eukaryotic cells display a wide variety of different cell morphologies. Possible shapes include spheroid, ovoid, cuboidal, cylindrical, flat, lenticular, fusiform, discoidal, crescent, ring stellate, and polygonal (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Some eukaryotic cells are irregular in shape, and some are capable of changing shape. The shape of a particular type of eukaryotic cell may be influenced by factors such as its primary function, the organization of its cytoskeleton, the viscosity of its cytoplasm, the rigidity of its cell membrane or cell wall (if it has one), and the physical pressure exerted on it by the surrounding environment and/or adjoining cells.

Nucleus

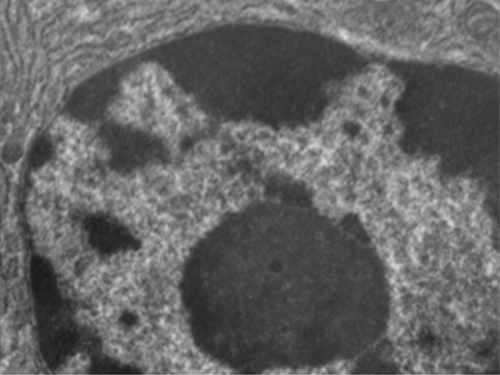

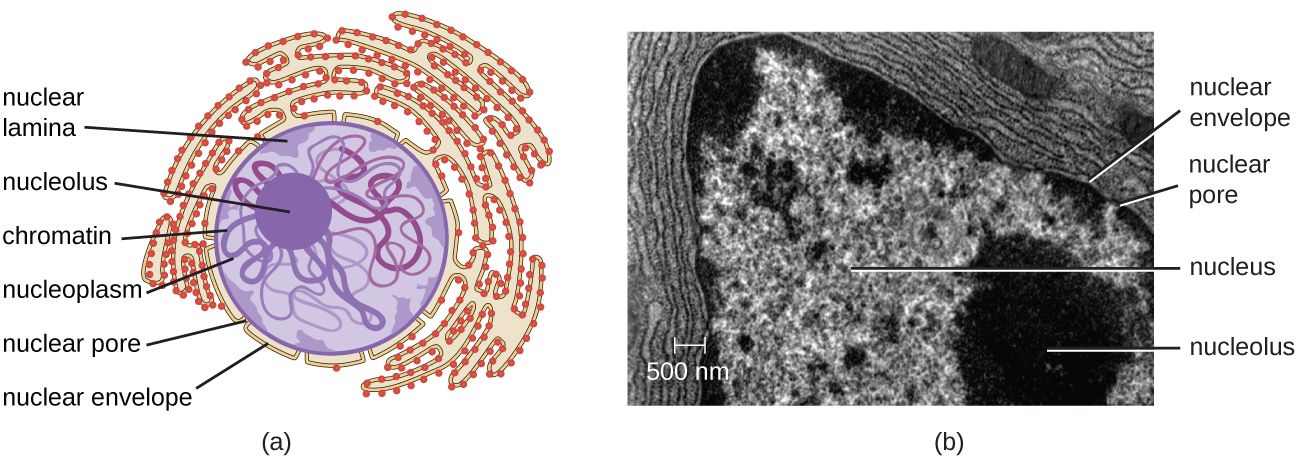

Unlike prokaryotic cells, in which DNA is loosely contained in the nucleoid region, eukaryotic cells possess a nucleus, which is surrounded by a complex nuclear membrane that houses the DNA genome (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). By containing the cell’s DNA, the nucleus ultimately controls all activities of the cell and also serves an essential role in reproduction and heredity. Eukaryotic cells typically have their DNA organized into multiple linear chromosomes. The DNA within the nucleus is highly organized and condensed to fit inside the nucleus, which is accomplished by wrapping the DNA around proteins called histones.

Although most eukaryotic cells have only one nucleus, exceptions exist. For example, protozoans of the genus Paramecium typically have two complete nuclei: a small nucleus that is used for reproduction (micronucleus) and a large nucleus that directs cellular metabolism (macronucleus). Additionally, some fungi transiently form cells with two nuclei, called heterokaryotic cells, during sexual reproduction. Cells whose nuclei divide, but whose cytoplasm does not, are called coenocytes.

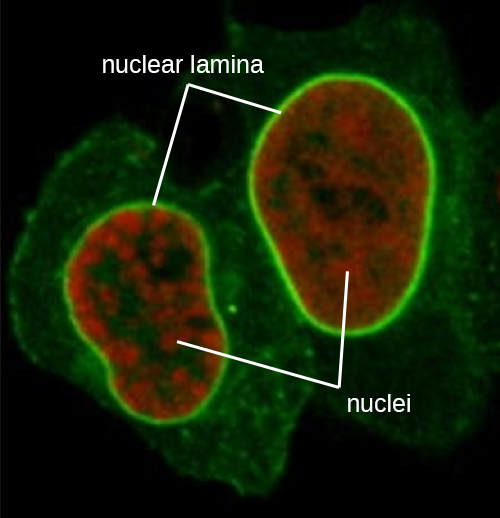

The nucleus is bound by a complex nuclear membrane, often called the nuclear envelope, that consists of two distinct lipid bilayers that are contiguous with each other (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Despite these connections between the inner and outer membranes, each membrane contains unique lipids and proteins on its inner and outer surfaces. The nuclear envelope contains nuclear pores, which are large, rosette-shaped protein complexes that control the movement of materials into and out of the nucleus. The overall shape of the nucleus is determined by the nuclear lamina, a meshwork of intermediate filaments found just inside the nuclear envelope membranes. Outside the nucleus, additional intermediate filaments form a looser mesh and serve to anchor the nucleus in position within the cell.

Nucleolus

The nucleolus is a dense region within the nucleus where ribosomal RNA (rRNA) biosynthesis occurs. In addition, the nucleolus is also the site where assembly of ribosomes begins. Preribosomal complexes are assembled from rRNA and proteins in the nucleolus; they are then transported out to the cytoplasm, where ribosome assembly is completed (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Ribosomes

Ribosomes found in eukaryotic organelles such as mitochondria or chloroplasts have 70S ribosomes—the same size as prokaryotic ribosomes. However, nonorganelle-associated ribosomes in eukaryotic cells are 80S ribosomes, composed of a 40S small subunit and a 60S large subunit. In terms of size and composition, this makes them distinct from the ribosomes of prokaryotic cells.

The two types of nonorganelle-associated eukaryotic ribosomes are defined by their location in the cell: free ribosomes and membrane-bound ribosomes. Free ribosomes are found in the cytoplasm and serve to synthesize water-soluble proteins; membrane-bound ribosomes are found attached to the rough endoplasmic reticulum and make proteins for insertion into the cell membrane or proteins destined for export from the cell.

The differences between eukaryotic and prokaryotic ribosomes are clinically relevant because certain antibiotic drugs are designed to target one or the other. For example, cycloheximide targets eukaryotic action, whereas chloramphenicol targets prokaryotic ribosomes.1 Since human cells are eukaryotic, they generally are not harmed by antibiotics that destroy the prokaryotic ribosomes in bacteria. However, sometimes negative side effects may occur because mitochondria in human cells contain prokaryotic ribosomes.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

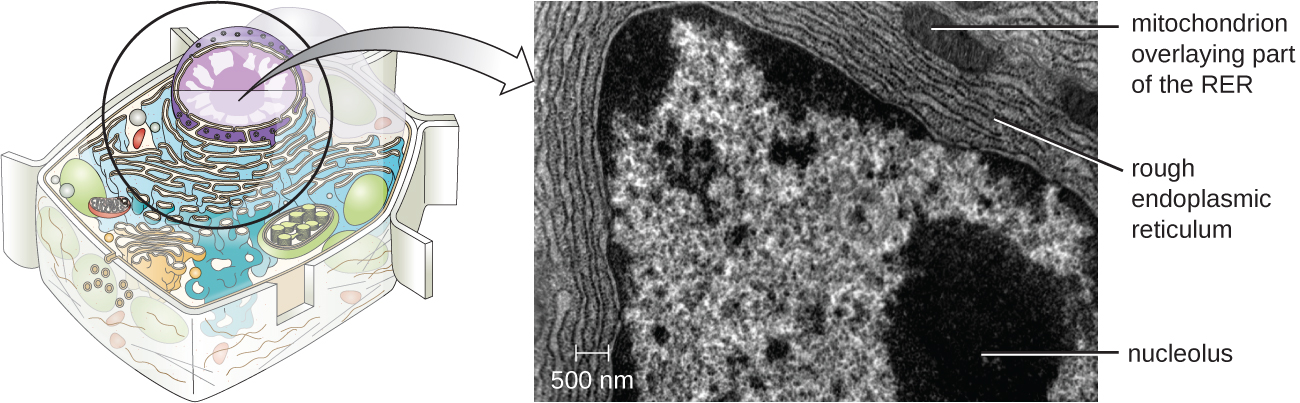

Endomembrane System

The endomembrane system, unique to eukaryotic cells, is a series of membranous tubules, sacs, and flattened disks that synthesize many cell components and move materials around within the cell (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Because of their larger cell size, eukaryotic cells require this system to transport materials that cannot be dispersed by diffusion alone. The endomembrane system comprises several organelles and connections between them, including the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and vesicles.

Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an interconnected array of tubules and cisternae (flattened sacs) with a single lipid bilayer (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). The spaces inside of the cisternae are called lumen of the ER. There are two types of ER, rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER). These two different types of ER are sites for the synthesis of distinctly different types of molecules. RER is studded with ribosomes bound on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. These ribosomes make proteins destined for the plasma membrane (Figure \(\PageIndex{}\)). Following synthesis, these proteins are inserted into the membrane of the RER. Small sacs of the RER containing these newly synthesized proteins then bud off as transport vesicles and move either to the Golgi apparatus for further processing, directly to the plasma membrane, to the membrane of another organelle, or out of the cell. Transport vesicles are single-lipid, bilayer, membranous spheres with hollow interiors that carry molecules. SER does not have ribosomes and, therefore, appears “smooth.” It is involved in biosynthesis of lipids, carbohydrate metabolism, and detoxification of toxic compounds within the cell.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

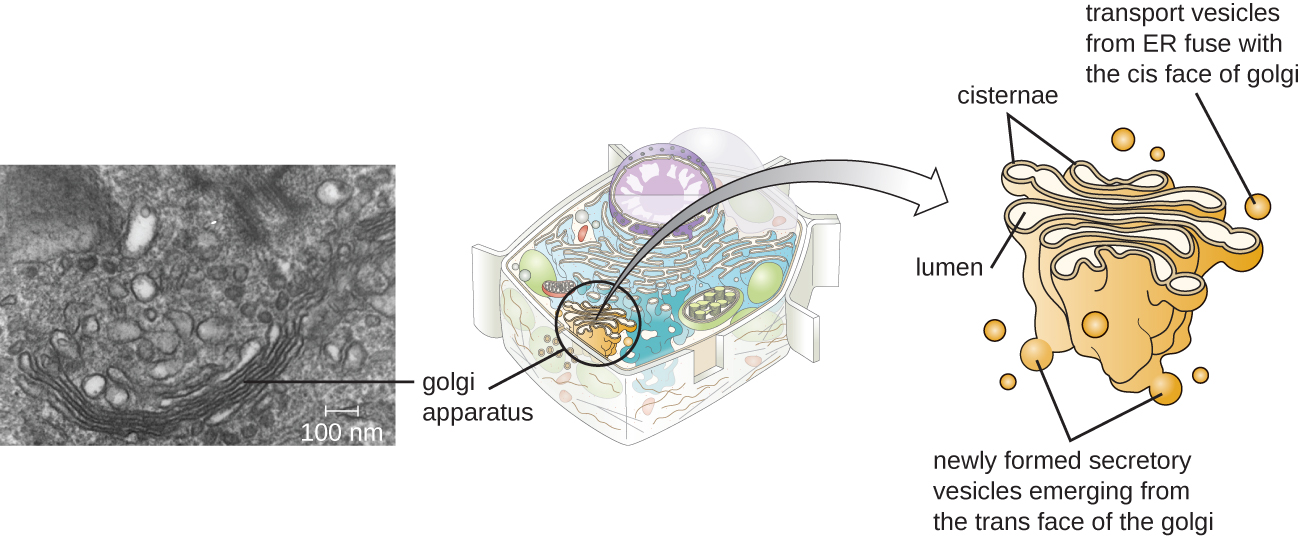

Golgi Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus was discovered within the endomembrane system in 1898 by Italian scientist Camillo Golgi (1843–1926), who developed a novel staining technique that showed stacked membrane structures within the cells of Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria. The Golgi apparatus is composed of a series of membranous disks called dictyosomes, each having a single lipid bilayer, that are stacked together (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)).

Enzymes in the Golgi apparatus modify lipids and proteins transported from the ER to the Golgi, often adding carbohydrate components to them, producing glycolipids, glycoproteins, or proteoglycans. Glycolipids and glycoproteins are often inserted into the plasma membrane and are important for signal recognition by other cells or infectious particles. Different types of cells can be distinguished from one another by the structure and arrangement of the glycolipids and glycoproteins contained in their plasma membranes. These glycolipids and glycoproteins commonly also serve as cell surface receptors.

Transport vesicles leaving the ER fuse with a Golgi apparatus on its receiving, or cis, face. The proteins are processed within the Golgi apparatus, and then additional transport vesicles containing the modified proteins and lipids pinch off from the Golgi apparatus on its outgoing, or trans, face. These outgoing vesicles move to and fuse with the plasma membrane or the membrane of other organelles.

Exocytosis is the process by which secretory vesicles (spherical membranous sacs) release their contents to the cell’s exterior (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). All cells have constitutive secretory pathways in which secretory vesicles transport soluble proteins that are released from the cell continually (constitutively). Certain specialized cells also have regulated secretory pathways, which are used to store soluble proteins in secretory vesicles. Regulated secretion involves substances that are only released in response to certain events or signals. For example, certain cells of the human immune system (e.g., mast cells) secrete histamine in response to the presence of foreign objects or pathogens in the body. Histamine is a compound that triggers various mechanisms used by the immune system to eliminate pathogens.

Lysosomes

In the 1960s, Belgian scientist Christian de Duve (1917–2013) discovered lysosomes, membrane-bound organelles of the endomembrane system that contain digestive enzymes. Certain types of eukaryotic cells use lysosomes to break down various particles, such as food, damaged organelles or cellular debris, microorganisms, or immune complexes. Compartmentalization of the digestive enzymes within the lysosome allows the cell to efficiently digest matter without harming the cytoplasmic components of the cell.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

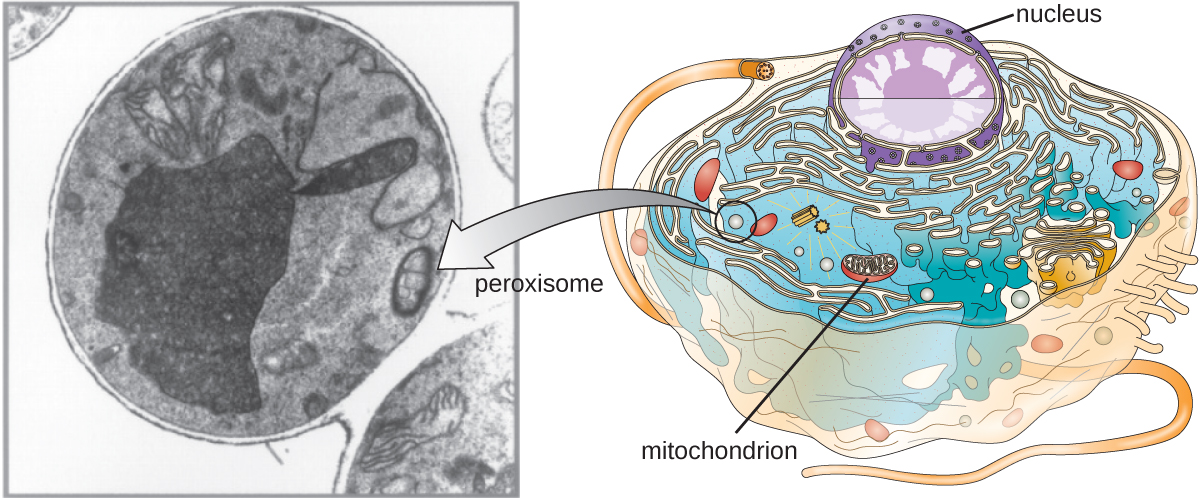

Peroxisomes

Christian de Duve is also credited with the discovery of peroxisomes, membrane-bound organelles that are not part of the endomembrane system (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Peroxisomes form independently in the cytoplasm from the synthesis of peroxin proteins by free ribosomes and the incorporation of these peroxin proteins into existing peroxisomes. Growing peroxisomes then divide by a process similar to binary fission.

Peroxisomes were first named for their ability to produce hydrogen peroxide, a highly reactive molecule that helps to break down molecules such as uric acid, amino acids, and fatty acids. Peroxisomes also possess the enzyme catalase, which can degrade hydrogen peroxide. Along with the SER, peroxisomes also play a role in lipid biosynthesis. Like lysosomes, the compartmentalization of these degradative molecules within an organelle helps protect the cytoplasmic contents from unwanted damage.

The peroxisomes of certain organisms are specialized to meet their particular functional needs. For example, glyoxysomes are modified peroxisomes of yeasts and plant cells that perform several metabolic functions, including the production of sugar molecules. Similarly, glycosomes are modified peroxisomes made by certain trypanosomes, the pathogenic protozoans that cause Chagas disease and African sleeping sickness.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Key Concepts and Summary

- Eukaryotic cells are defined by the presence of a nucleus containing the DNA genome and bound by a nuclear membrane (or nuclear envelope) composed of two lipid bilayers that regulate transport of materials into and out of the nucleus through nuclear pores.

- Eukaryotic cell morphologies vary greatly and may be maintained by various structures, including the cytoskeleton, the cell membrane, and/or the cell wall.

- The nucleolus, located in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells, is the site of ribosomal synthesis and the first stages of ribosome assembly.

- Eukaryotic cells contain 80S ribosomes in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (membrane bound-ribosomes) and cytoplasm (free ribosomes). They contain 70s ribosomes in mitochondria and chloroplasts.

- Eukaryotic cells have evolved an endomembrane system, containing membrane-bound organelles involved in transport. These include vesicles, the endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi apparatus.

- The smooth endoplasmic reticulum plays a role in lipid biosynthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, and detoxification of toxic compounds. The rough endoplasmic reticulum contains membrane-bound 80S ribosomes that synthesize proteins destined for the cell membrane

- The Golgi apparatus processes proteins and lipids, typically through the addition of sugar molecules, producing glycoproteins or glycolipids, components of the plasma membrane that are used in cell-to-cell communication.

- Lysosomes contain digestive enzymes that break down small particles ingested by endocytosis, large particles or cells ingested by phagocytosis, and damaged intracellular components.

- The cytoskeleton, composed of microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules, provides structural support in eukaryotic cells and serves as a network for transport of intracellular materials.

- Centrosomes are microtubule-organizing centers important in the formation of the mitotic spindle in mitosis.

- Mitochondria are the site of cellular respiration. They have two membranes: an outer membrane and an inner membrane with cristae. The mitochondrial matrix, within the inner membrane, contains the mitochondrial DNA, 70S ribosomes, and metabolic enzymes.

- The plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells is structurally similar to that found in prokaryotic cells, and membrane components move according to the fluid mosaic model. However, eukaryotic membranes contain sterols, which alter membrane fluidity, as well as glycoproteins and glycolipids, which help the cell recognize other cells and infectious particles.

- In addition to active transport and passive transport, eukaryotic cell membranes can take material into the cell via endocytosis, or expel matter from the cell via exocytosis.

- Cells of fungi, algae, plants, and some protists have a cell wall, whereas cells of animals and some protozoans have a sticky extracellular matrix that provides structural support and mediates cellular signaling.

- Eukaryotic flagella are structurally distinct from prokaryotic flagella but serve a similar purpose (locomotion). Ciliaare structurally similar to eukaryotic flagella, but shorter; they may be used for locomotion, feeding, or movement of extracellular particles.

Footnotes

- 1 A.E. Barnhill, M.T. Brewer, S.A. Carlson. “Adverse Effects of Antimicrobials via Predictable or Idiosyncratic Inhibition of Host Mitochondrial Components.” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 56 no. 8 (2012):4046–4051.

- 2 Fuchs E, Cleveland DW. “A Structural Scaffolding of Intermediate Filaments in Health and Disease.” Science 279 no. 5350 (1998):514–519.

- 3 E. Fuchs, D.W. Cleveland. “A Structural Scaffolding of Intermediate Filaments in Health and Disease.” Science 279 no. 5350 (1998):514–519.

- 4 E. Fuchs, D.W. Cleveland. “A Structural Scaffolding of Intermediate Filaments in Health and Disease.” Science 279 no. 5350 (1998):514–519.

- 5 N. Yarlett, J.H.P. Hackstein. “Hydrogenosomes: One Organelle, Multiple Origins.” BioScience 55 no. 8 (2005):657–658.

- 6 M. Dudzick. “Protists.” OpenStax CNX. November 27, 2013. http://cnx.org/contents/f7048bb6-e46...ef291cf7049c@1