14.1: Regulation of Metabolic Pathways

- Page ID

- 15011

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)-

Explain the Importance of Metabolic Regulation:

- Describe how cells balance metabolite flux to meet biological demands and conserve energy (ATP).

- Compare the cellular consequences of unregulated versus tightly controlled metabolic pathways.

-

Differentiate Between Regulatory Mechanisms:

- Distinguish between regulation by changing the activity of preexisting enzymes and altering the enzyme concentration.

- Provide examples of each mechanism in cellular metabolism.

-

Analyze Enzyme Kinetics in Regulation:

- Interpret the significance of substrate concentration relative to the Km in determining enzyme activity.

- Explain how substrate availability affects the velocity of an enzymatic reaction.

-

Evaluate Inhibition Strategies:

- Illustrate how product inhibition and end-product feedback serve as regulatory mechanisms to prevent unnecessary enzyme activity.

- Discuss the physiological benefits of these inhibition mechanisms.

-

Understand Allosteric Regulation and pH Effects:

- Explain how binding of effectors at allosteric sites can modulate enzyme conformation and activity.

- Analyze the dual impact of pH on overall enzyme conformation versus specific active site protonation states.

-

Discuss Covalent Modifications:

- Identify common post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation) and explain how they alter enzyme function.

- Use the example of ERK2 phosphorylation to illustrate how covalent modifications can change enzyme conformation and activity.

-

Examine the Concept of Enzyme Condensates:

- Describe how the assembly of enzymes into condensates (or supramolecular complexes) can coordinate pathway regulation.

- Analyze the role of enzyme polymerization in regulating flux through metabolic pathways.

-

Assess Regulation at the Transcriptional and Translational Levels:

- Explain how extracellular signals affect the transcription of enzyme-coding genes.

- Discuss the role of mRNA degradation and co/post-translational modifications in controlling enzyme concentration and activity.

-

Integrate Thermodynamic Principles in Metabolic Regulation:

- Relate the concepts of ΔG and ΔG° to enzyme-catalyzed reactions, particularly in reactions far from equilibrium.

- Evaluate why enzymes catalyzing irreversible or “committed” steps are prime targets for regulation.

-

Apply Analogies to Understand Metabolic Flux:

- Use the water flow (pipe and valve) analogy to explain how cells regulate the flow of metabolites through a pathway.

- Critically assess how this analogy aids in understanding the dynamics of metabolic control.

These learning goals will not only help students grasp the molecular and kinetic details of enzyme regulation but also encourage them to integrate structural, thermodynamic, and systems biology perspectives into their understanding of metabolism.

Exquisite mechanisms have evolved to control the flux of metabolites through metabolic pathways, ensuring that the output of these pathways meets biological demand and that energy in the form of ATP is not wasted by having opposing pathways run concurrently in the same cell.

Enzymes can be regulated by changing the activity of a preexisting enzyme or the amount of an enzyme.

Changing the activity of a pre-existing enzyme

The quickest way to modulate the activity of an enzyme is to alter the activity of an enzyme that already exists in the cell. The list below, illustrated in the following figure, outlines common methods for regulating enzyme activity.

- Substrate availability: Substrates (reactants) bind to enzymes with a characteristic affinity (characterized by a dissociation constant) and a kinetic parameter called Km (units of molarity). If the actual concentration of a substrate in a cell is much less than the Km, the enzyme's activity is very low. If the substrate concentration is much greater than Km, the enzyme's active site is saturated with substrate, and the enzyme is maximally active.

- Product inhibition: A product of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction often resembles a starting reactant, so it should be clear that the product also binds to the active site, albeit with probably lower affinity. Under conditions in which the product of a reaction is present in high concentration, it would be energetically advantageous to the cell if no more product were synthesized. Product inhibition is hence commonly observed. Likewise, it is energetically advantageous to a cell if the end product of an entire pathway could likewise bind to the initial enzyme in the pathway and inhibit it, allowing the whole pathway to be inhibited. This type of feedback inhibition is commonly observed. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows product and end-product inhibition.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Product and end product inhibition of an enzyme

- Allosteric regulation: As many pathways are interconnected, it would be optimal if the molecules of one pathway affected the activity of enzymes in another interconnected pathway, even if the molecules in the first pathway are structurally dissimilar to reactants or products in a second pathway. Molecules that bind to sites on target enzymes other than the active site (allosteric sites) can regulate the activity of the target enzyme. These molecules can be structurally dissimilar to those that bind at the active site. They do so by conformational changes that activate or inhibit the target enzyme's activity.

- pH and enzyme conformation: Changes in pH that accompany metabolic processes, such as respiration (aerobic glycolysis, for example), can alter the conformation of an enzyme and, consequently, its activity. The initial changes are covalent (change in the protonation state of the protein), which can alter the delicate balance of forces that affect protein structure.

- pH and active site protonation state: Changes in pH can affect the protonation state of key amino acid side chains in the active site of proteins without affecting the local or global conformation of the protein. Catalysis may be affected if the mechanism involves an active site nucleophile (for example) that must be deprotonated for activity.

- Covalent modification: Many, if not most, proteins undergo post-translational modifications, which can alter enzyme activity through local or global shape changes by promoting or inhibiting binding interactions between substrates and allosteric regulators. They can also change the location of the protein within the cell. Proteins may be phosphorylated, acetylated, methylated, sulfated, glycosylated, amidated, hydroxylated, prenylated, or myristoylated, often in a reversible manner. Some of these modifications are reversible. Regulation by phosphorylation, through the action of kinases, and dephosphorylation, by phosphatases, is extremely common. Control of the phosphorylation state is mediated through signal transduction processes starting at the cell membrane, leading to the activation or inhibition of protein kinases and phosphatases within the cell.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) illustrates methods for regulating the activity of pre-existing enzymes.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Ways to regulate the activity of pre-existing enzymes

Extracellular regulated kinase 2 (ERK2), also known as mitogen-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPK2), plays a vital role in cell signaling across the cell membrane. Phosphorylation of ERK2 on Threonine 183 (Thr183) and Tyrosine 185 (Tyr185) leads to a structural change in the protein and regulates its activity.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model showing the structural alignment of ERK2 in the dephosphorylated (5UMO) and phosphorylated (pY185) forms (2ERK). Toggle back and forth between the two structures with the "a" key.

The residues that change significantly in conformation on phosphorylation are shown in blue. The side chain of tyrosine 185 in the unphosphorylated form is shown in CPK-colored sticks and labeled.

Regulation of single enzymes or entire pathways: Enzyme condensates

Single enzymes or all the enzymes of a given pathway can be coordinately regulated to maximize end-product output by organizing the enzymes in one large complex built from soluble enzymes that produce a "condensate" through a process similar to phase separation. Such condensates are shown for a series of enzymes in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Supramolecular assembly of enzyme condensates. Prouteau and Loewith. Biomolecules 2018, 8(4), 160; https://doi.org/10.3390/biom8040160. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

The figure shows metabolism-related enzymes that form polymers in various organisms.

Panel (a) shows examples of metabolic enzymes observed to coalesce into cytosolic condensates.

Panel (b) top shows structures of metabolic enzymes that polymerize into filaments. The protomer of the polymer is shown above and placed into the filament below. These include P-Fructo-Kinase (4XYJ), cytidine triphosphate synthase (5U03), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (6G2D), glutamine synthetase (3FKY), mTORC1 (5FLC) from PDB files.

Panel (b) bottom shows the same structures from the Electron Microscopy Data Bank, including P-Fructo-Kinase filament (emd-8542), human CTP synthase filament (and-8474), human acetyl-CoA carboxylase with citrate (emd-4342), and the yeast glutamine synthetase filament.

Changing the amount of an enzyme

Another method to modulate the activity of an enzyme is to alter the activity of an existing enzyme in the cell. Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows how enzyme concentrations are regulated.

Methods include:

- Alterations in the transcription of an enzyme's gene: Extracellular signals (hormones, neurotransmitters, etc.) can lead to signal transduction responses and ultimately activate or inhibit the transcription of the gene for a protein enzyme. These changes result from the recruitment of transcription factors (proteins) to DNA sequences that regulate the transcription of the enzyme gene.

- Degradation of messenger RNA for the enzyme: The levels of messenger RNA for a protein directly determine the amount of that protein synthesized. Two key proteins are involved in an RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. The RNase Dicer produces 21–25 nt small single-stranded RNAs (siRNAs or miRNAs) which can bind the protein Argonaute. The bound siRNA (a guide RNA) finds a complementary sequence on a specific mRNA, leading to the chemical modification or cleavage of the mRNA, silencing its translation into a protein.

- Co/Post-translational changes: Once a protein enzyme is translated from its mRNA, it can undergo many changes that regulate its activity. Some proteins are synthesized in a "pre" form, which proteases must cleave in a targeted and limited fashion to activate the protein enzyme. Some proteins are not fully folded and must bind to other cellular factors to adopt a catalytically active form. Finally, a fully active protein can be fully proteolyzed by the proteasome, a complex within cells or in lysosomes, organelles within cells that contain proteolytic enzymes.

The concentrations of all proteins are affected by their relative rates of synthesis and degradation. However, some enzymes positioned at key points in metabolic pathways are ideal candidates for regulation, as their activity can affect the output of entire pathways. These enzymes typically have two common characteristics: they catalyze reactions far from equilibrium, and they catalyze early committed steps in pathways.

Which Enzymes to Regulate: Reactions not at Equilibrium

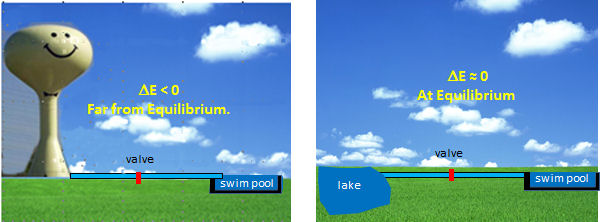

The optimal enzymes for regulation are those located at the beginning of pathways that catalyze thermodynamically favored reactions. Why is the latter so important? These enzymes control the flux of metabolites through pathways; therefore, to understand their regulation, we can use the analogy of water flow (or flux) from one container to another, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Regulation of water flow in pipe

Let's say you wish to fill a swimming pool to a desired height, and you have two options to do so (see the figure below). You could open a valve that controls the flow from your town's water tower to the pool. In this, the reaction (flow of water) is energetically (thermodynamically) favored given the difference in height of the water levels and the potential energy difference between the two. Even though flow (or flux) is flavored, you can regulate it, from maximal flow to no flow, by opening and closing the valve (analogous to activating and inhibiting an enzyme). In the other scenario, where you fill the pool from a lake, your options are limited. It would be hard to fill the water to the desired level (especially if it were an above-ground pool). It would be hard to regulate the flow.

By analogy, the best candidates for regulation are those enzymes whose reactions are thermodynamically favored (i.e., not at equilibrium) but can be controlled by the mechanisms discussed in the previous section.

Which reactions are commonly not at equilibrium? Let's quickly review a key thermodynamic equation for the reversible conversion of reactants A and B to products P and Q:

\begin{equation}

\Delta G=\Delta G^0+R T \ln \frac{[\mathrm{P}][\mathrm{Q}]}{[\mathrm{A}][\mathrm{B}]}=\Delta G^0+R T \ln \mathrm{Q}_{\mathrm{rx}}

\end{equation}

In reactions that are favored in the forward direction, ΔG < 0. If ΔGo < 0, the forward reaction is favored unless the ratio of products to reactants is too high. ΔGo < 0 if the reactants are chemically unstable compared to the products. Several types of reactions often fit these criteria.

Hydrolysis (or similar reactions) of anhydride or analogous motifs.

Figure 7 below shows molecules with similar "anhydride" motifs and the ΔG° for the hydrolysis of these molecules. Those with more negative ΔG0 values can transfer their phosphate group to ADP to make ATP, which is necessary to drive unfavorable biological reactions. Metabolic reactions that involve hydrolysis (or other types of transfer reaction of these groups) usually proceed with a negative ΔG0 and ΔG, making them prime candidates for pathway regulation. Many textbooks label these molecules as having "high-energy" bonds. This confuses many students as bonds between atoms lower the energy compared to when the atoms are not bonded. It takes energy to break the "high" energy phosphoanhydride covalent bond. The hydrolysis of the molecules below is exergonic because more energy is released during bond formation in the new products than was required to break the bonds in the reactants. In addition, other effects, such as preferential hydration of the products, lower charge density, and fewer competing resonances in the products, all contribute to the thermodynamically favorable hydrolysis of the reactants.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows the structures of thermodynamically unstable metabolites (compared to their reaction products in aqueous solutions) and their ΔG0hydrolysis.

Thioesters

Thioesters (such as Acetyl-SCoA) are also included in Figure 7, as they have the same negative ΔG° of hydrolysis as ATP, even though they lack an "anhydride" motif. Thioesters are destabilized compared to their hydrolysis products (a carboxylic acid and a thiol) compared to esters made with alcohol, since the C-S bond in the reactant is weaker. The S atom is larger than an O atom, so the C-S bond length is longer than a C-O bond. The lone pair on the S can't delocalize as readily to form a C=S double bond in the reactant through resonance. This destabilizes the reactant, the thioester, compared to a regular carboxylic acid ester. This, in turn, increases the ΔG° of hydrolysis of the thioester compared to the product, the free thiol.

Redox reactions

Most students likely recall that redox reactions are thermodynamically favored if the oxidizing agent deployed is strong enough. The full oxidation reactions of hydrocarbons, sugars, and fats by dioxygen are clearly exergonic (think burning of wood!). What about redox reactions with less powerful oxidants? NAD+ is frequently used as a biological oxidizing agent. Are all these reactions as favored as combustion? Hardly so. Remember that in every redox reaction, an oxidizing and reducing agent react to form another oxidizing and reducing agent. Consider the following reaction:

Pyruvate + NADH ↔ Lactate + NAD+

This reaction can proceed in either direction and is reversible. The above form is written in the favored direction in anaerobic metabolism when both Pyr and NADH levels are high. Although the ΔG0 favors lactate oxidation, given the high concentration of Pyr and NADH, the reaction is driven in the opposite direction and proceeds as shown. To determine if a redox reaction is favored and likely to occur (and possibly be regulated), the ΔG0 for a redox reaction should be calculated from standard reduction potentials, using the formula ΔG0 = -nFE0.

Which Enzymes to Regulate: Those catalyzing committed steps in pathways

The best enzymes for regulation catalyze the first committed step in the reaction pathway. The committed step proceeds with a ΔG0 < 0 and is essentially irreversible. These reactions often occur from key metabolic intermediates immediately before or proximal to branches in reaction pathways. Two examples of key intermediates at branch points of metabolic pathways are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\), which illustrates the reactions involved in the production and utilization of the intermediate glucose-6-phosphate.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Reactions for the production and use of the intermediate glucose-6-phosphate

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) shows reactions for producing and using the intermediate acetyl-CoA.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Reactions for the production and use of the intermediate acetyl-CoA

In reality, metabolic regulation is more complex and is distributed to many steps in a reaction pathway in ways that might not be evident without detailed mathematical analyses. We will discuss that in the following sections on metabolic control analysis.

Summary

This chapter provides an in-depth look at the sophisticated regulatory mechanisms that control metabolic pathways, ensuring that cells meet their energetic and biosynthetic demands without wasting resources. Key points include:

-

Balancing Metabolic Flux:

Cells utilize exquisite regulatory strategies to direct metabolite flux, thereby matching pathway outputs to biological needs while conserving ATP. -

Two Main Regulatory Approaches:

-

Modulating Enzyme Activity:

- Substrate Availability: Enzyme activity is influenced by how substrate concentration compares with the enzyme’s Km.

- Product Inhibition: End-products or intermediates can bind to enzymes, reducing further product formation and saving energy.

- Allosteric Regulation: Binding of effectors at sites other than the active site induces conformational changes that either activate or inhibit enzymes.

- pH Effects: Changes in pH can alter both the overall conformation of enzymes and the protonation states of key active site residues, thus modulating catalytic activity.

- Covalent Modifications: Post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation, acetylation) can rapidly alter enzyme activity, as exemplified by the phosphorylation-induced conformational change in ERK2.

-

Adjusting Enzyme Concentration:

- Transcriptional Control: Extracellular signals can activate or repress the transcription of genes coding for metabolic enzymes.

- mRNA Stability: Regulation of mRNA degradation through mechanisms such as microRNA binding directly influences enzyme levels.

- Co/Post-Translational Processing: Activation or inactivation of enzymes through proteolytic cleavage or folding, and their eventual degradation via proteasomes or lysosomes, further fine-tune enzyme abundance.

-

-

Enzyme Condensates:

The formation of supramolecular assemblies or condensates allows for the coordinated regulation of multiple enzymes within a pathway, enhancing the efficiency and responsiveness of metabolic control. -

Thermodynamic Considerations:

Enzymes catalyzing reactions far from equilibrium (ΔG < 0) and those that mediate the committed, irreversible steps of metabolic pathways are optimal control points. This chapter explains how the hydrolysis of “high energy” bonds (e.g., in ATP or thioesters like Acetyl-SCoA) and redox reactions drive these irreversible steps. -

Practical Analogy:

An analogy comparing metabolic regulation to controlling water flow with a valve illustrates how precise regulation of enzyme activity can control the “flow” of metabolites in a pathway, ensuring the right output without waste.

Overall, the chapter integrates structural, kinetic, and thermodynamic perspectives, providing a comprehensive framework that junior and senior biochemistry majors can build upon to understand metabolic control and its importance in cellular physiology.

_and_phospho_(pY185)_forms_(2ERK).png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=407&height=252)