9.2: Monosaccharides

- Page ID

- 154244

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

- Core terminology: Define sugar, carbohydrate, and glycan; distinguish monosaccharides from larger glycans.

- Structures and representations: Identify stereocenters and convert among Fischer, Haworth, chair, and wedge/dash for D-glucose, D-ribose, and D-fructose.

- Cyclization and anomers: Explain hemiacetal ring formation to furanose or pyranose, locate the anomeric carbon, distinguish α and β, and describe mutarotation and ring populations.

- Reducing behavior and derivatives: Explain reducing behavior via ring opening to an aldehyde or α-hydroxyketone, and recognize common derivatives (oxidation, phosphorylation, amination, acetylation, lactonization) and their roles.

These goals prepare students to analyze and predict properties of monosaccharides.

Introduction

Carbohydrate or glycan biochemistry is very complex and challenging owing to the stereochemical complexity of simple sugars, the large number of positions on the sugars used to form linkages between other sugars to create polymers, the large number of chemical modifications to base sugars, and the lack of a genetic template to instruct glycan polymer formation. No wonder our understanding of complex glycans has developed after that of the chemically simpler polymers like nucleic acids and proteins.

In addition, the terminology used to describe them varies as well. We use these general descriptions of them:

Sugar: usually refers to low molecular weight carbohydrates like glucose, lactose, and sucrose, but it can also refer broadly to any carbohydrate.

Carbohydrate: a general term that applies to simple sugars to complex sugar polymers like glycogen, starch, and cellulose. The name derives from the formula for simple sugars like glucose (C6H12O6), which can be written as C6(H2O)6 - a carbo (C) - hydrate (H2O).

Glycan: a general term for molecules containing simple sugars and sugar derivatives linked in a polymer, either standalone molecules or attached to other molecules like proteins.

Classification of Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides are classified along a few orthogonal axes. Use these labels together when naming and comparing structures.

- Carbonyl type: aldose (aldehyde at C1) or ketose (ketone). For ketoses, specify the carbonyl position when not at C2 (for example, 3-ketose or the stem hex-3-ulose).

- Carbon count: triose, tetrose, pentose, hexose, heptose, etc. Combine with carbonyl type (for example, aldohexose, ketopentose).

- D/L configuration: assigned by the stereocenter farthest from the carbonyl, by reference to D-glyceraldehyde. D/L does not predict optical rotation.

- Ring size in solution: furanose (5-member) or pyranose (6-member). Report the common ring if relevant (for example, β-D-ribofuranose vs β-D-glucopyranose).

- Common epimer pairs: D-glucose/D-mannose (C2 epimers), D-glucose/D-galactose (C4 epimers); D-ribose/D-arabinose/D-xylose/D-lyxose vary at C2–C4.

- Frequent derivatives (name stems): deoxy- (for example, 2-deoxyribose), -onic acids (C1 oxidation), -uronic acids (C6 oxidation), amino sugars (GlcN, GalN), N-acetylated forms (GlcNAc, GalNAc), phosphates (for example, Glc-6-P).

Naming tip: A precise name can stack these labels, for example “β-D-arabino-hex-3-ulose” or “α-D-glucopyranose-6-phosphate.”

Carbonyl type

Aldose has an aldehyde in the open chain at C1. Ketose has a ketone internal to the chain. When the ketone is not at C2, state its position (for example, 3-ketose; systematic stem “hex-3-ulose”). In a Fischer projection, an aldose shows the carbonyl at the top carbon; a ketose shows a C=O lower in the chain. In a Haworth projection, find the carbon bonded to two oxygens (ring O and the anomeric substituent); C1 implies an aldose, C2 a 2-ketose, C3 a 3-ketose.

Carbon count

Triose, tetrose, pentose, hexose, heptose, and so on. Combine with carbonyl type (for example, aldohexose, ketopentose). In a Fischer projection, number from the carbonyl carbon and count the backbone. In a Haworth projection, count ring atoms and include the exocyclic CH2OH to reach the open-chain carbon total.

D/L configuration

Assign by the stereocenter farthest from the carbonyl in the open chain. If the OH at that center points right in the Fischer projection it is D, left is L. D/L does not predict optical rotation. In the standard Haworth orientation used here, D-pyranoses show the terminal CH2OH drawn up, L-pyranoses down.

Ring size in solution

Five-member rings are furanoses and six-member rings are pyranoses. For common D-aldoses, intramolecular attack of O5 on C1 gives a pyranose; attack of O4 on C1 gives a furanose. For 2-ketoses, attack of O5 on C2 gives a furanose, while attack of O6 on C2 gives a pyranose. In Haworth, count the ring atoms to name furanose or pyranose and report the prevalent form when relevant.

Anomeric carbon and α/β

The anomeric carbon is the former carbonyl after ring closure (C1 in aldoses, C2 in 2-ketoses, C3 in 3-ketoses). Assign α or β only at anomeric carbons. In Haworth, compare the anomeric OH to the CH2OH-bearing carbon: for the D series, α is trans to CH2OH and β is cis. In pyranoses drawn in the standard orientation, this appears as α down and β up.

Monosaccharides Structures

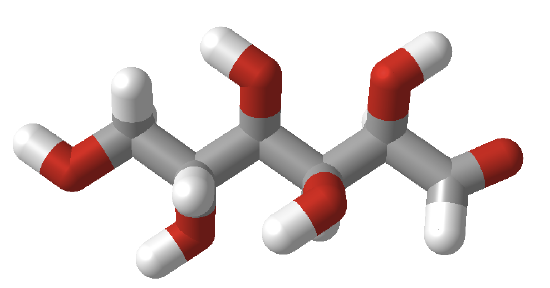

The above definition of sugar needs some further nuance. From a chemical perspective, sugars can be defined as polyhydroxy-aldehydes or ketones. The simplest sugars contain at least three carbon atoms, and the most common are the aldo- and keto-trioses, tetroses, pentoses, and hexoses. The 3C sugars are glyceraldehyde and dihydroxyacetone, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Three-carbon sugars

Glucose, an aldohexose, is a central sugar in metabolism. It and other 5C and 6C sugars can cyclize through intramolecular nucleophilic attack of one of the free hydroxyl groups on the carbonyl carbon of the aldehyde or ketone. Such intramolecular reactions occur if stable 5- or 6-member rings can form. The resulting rings are labeled furanose (5-member) or pyranose (6-member) based on their similarity to furan and pyran. On nucleophilic attack to form the ring, the carbonyl O becomes an OH that points either below (α anomer) or above (β anomer) the ring.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows different representations of the linear and cyclic forms of the sugars D-glucose, D-ribose, and D-fructose

Monosaccharides in solution exist as equilibrium mixtures of the straight and cyclic forms. In solution, glucose (Glc) is mainly in the pyranose form, fructose is 67% pyranose and 33% furanose, and ribose is 75% furanose and 25% pyranose. However, in polysaccharides, Glc is exclusively pyranose, and fructose and ribose are furanoses.

Sugars can be drawn in the straight chain form as Fischer projections or perspective structural formulas.

In the Fischer projection, the vertical bonds point down into the plane of the paper. That's easy to visualize for 3C sugars, but more complicated for larger ones. For those, draw a wedge and dash line drawing of the molecule. When determining the orientation of the OHs on each C, orient the wedge and dash drawing in your mind so that the C atoms adjacent to the one of interest are pointing down. Sighting towards the carbonyl C, if the OH is pointing to the right in the Fischer project, it should be pointing to the right in the wedge and dash drawing, as shown below for D-threose and D-glucose. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows how to convert Fischer projections to wedge dash representations.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of D-glucose in a linear form.

Orient the molecule as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) below, with the carbonyl oxygen pointed to the far right, and compare it to the orientation shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) to reinforce your understanding of Fischer and wedge/dash projections.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\):

Cyclic forms can be drawn either as the Haworth projections, which show the molecule as cyclic and planar with substituents above or below the ring, or the more plausible bent forms (showing glucose in the chair or boat conformations). β-D-glucopyranose is the only aldohexose that can be drawn with all its bulky substituents (OH and CH2OH) in equatorial positions, which probably accounts for its widespread prevalence in nature. Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) shows four different representations of glucose.

Haworth projections are more realistic than the Fischer projections, but you should be able to draw both structures. Generally, if a substituent points to the right in the Fischer projection, it points down in the Haworth projection. If it points left, it points up. Generally, the OH on the α-anomer points down (αnts down) while on the β-anomer, it points up (βutterflies up) as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)

In the Haworth projections, the bulky R group of the next carbon after the carbon whose OH group was the nucleophile for ring formation is pointed up if the OH engaged in the attack was on the right-hand side in the straight chain Fischer diagram (as in α-D-glucopyranose above, when the CH2OH group is up). Conversely, it is pointed down if the OH engaged in the attack was on the left-hand side in the straight chain Fischer diagram (as in α-D-galactofuranose above when the (CHOH)CH2OH group is down). The rest of the OH groups still follow the simple rule that if they point to the right in the Fischer projection, they point down in the Haworth projection.

The Fischer structures of the most common monosaccharides (other than glyceraldehyde and dihydroxyacetone), which you will encounter most frequently, are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Most common monosaccharides discussed in this book

The mirror image of D-Glc is L-Glc. The D- and L- designations refer to the center of asymmetry most remote from the aldehyde or ketone. By convention, all chiral centers are related to D-glyceraldehyde, so sugar isomers related to D-glyceraldehyde at their last asymmetric center are D sugars.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows multiple renderings of common hexoses.

Isomers

Sugars can be configurational (interconverted only by breaking covalent bonds) or conformational isomers. Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) reviews different configurational isomers.

The configurational isomers include enantiomers (stereoisomers that are mirror images of each other), diastereomers (stereoisomers that are not mirror images), epimers (diastereomers that differ at one stereocenter), and anomers (a particular form of stereoisomer, diastereomer, and epimer). Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) below shows enantiomers, diastereomers, epimers, and anomers of 6-carbon sugars.

Sugars can also exist as conformational isomers, which interchange without breaking covalent bonds. These include chair and boat conformations of the cyclic sugars as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

Monosaccharide Derivatives

Many derivatives of monosaccharides are found in nature. These include

- oxidized forms in which the aldehyde and/or alcohol functional groups are oxidized to carboxylic acids

- phosphorylated forms in which phosphates are transferred from ATP to form phosphoester derivatives

- amine derivatives such as glucosamine or galactosamine

- acetylated amine derivatives such as N-Acetyl-GlcNAc (GlcNAc) or GalNAc

- lactone forms (intramolecular esters) in which an OH group attacks a carbonyl C that was previously oxidized to a carboxylic acid

- condensation products of sugar derivatives with lactate (CH3CHOHCO2-) and pyruvate (CH3COCO2- ), both from the glycolytic pathway, to form muramic acid and neuraminic acids (also called sialic acids), respectively.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) some simple monosaccharide derivatives.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows some additional oxidative derivatives of glucose shown in Fischer projections.

Other important derivatives of monosaccharides are sialic acids. N-acetylmuramic acid, found in bacterial cell walls, consists of GlcNAc in an ether link at C3 with lactate, while N-acetylneuraminic acid results from an intramolecular cyclization of a condensation product of ManNAc and pyruvate. These sialic acids are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\).

Sugars are very complicated, as the linkages and substituents are so diverse. Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) shows differences in sialic acids between humans and chimps.

What happens when non-vegan humans eat animal products (meat, milk) with N-glycoyl neuraminic acids (Neu5Gc)? Some get incorporated into human membrane glycans. Sialic acids on surface proteins can serve as "receptors" that allow the binding of self-cells as well as foreign cells or proteins that have evolved to bind them. A toxin, SubAB, secreted by E. Coli 0157, can bind Neu5Gc. Hence, eating meat products can make us more susceptible to bacteria that recognize Neu5Gc.

Formation of Hemiacetals and Acetals

Monosaccharides that contain aldehydes can cyclize through an intramolecular nucleophilic attack of an OH at the carbonyl carbon in an addition reaction to form a hemiacetal. In the past, the group was called a hemiketal if the attack was on a ketone, but now they are also called hemiacetals. On the addition of acid (which protonates the anomeric OH, forming water as a potential leaving group), another alcohol can add, forming an acetal with water leaving. These reactions are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\).

Summary

This chapter provides an in-depth exploration of the complexity of carbohydrate chemistry, emphasizing the structural, stereochemical, and functional diversity of sugars and glycans. It highlights why glycan biochemistry is particularly challenging due to the vast array of possible structures that arise from simple monosaccharide building blocks.

Key topics include:

-

Terminology and Definitions:

The chapter begins by clarifying the terms "sugar," "carbohydrate," and "glycan." While "sugar" typically refers to small, low molecular weight carbohydrates like glucose, the term "carbohydrate" encompasses everything from simple sugars to complex polymers such as glycogen and cellulose. "Glycan" is used more generally to describe any polymer of sugars, whether free or attached to proteins and lipids. -

Monosaccharide Structures and Representations:

An overview of monosaccharide structures is provided, including the chemical basis of sugars as polyhydroxy-aldehydes or ketones. The chapter explains how simple sugars (e.g., trioses, tetroses, pentoses, hexoses) can cyclize to form stable 5-membered (furanose) or 6-membered (pyranose) rings. Various methods of structural representation are compared, such as Fischer projections, Haworth projections, and chair conformations, highlighting the stereochemical intricacies and the significance of α- and β-anomers. -

Isomerism and Structural Diversity:

The text reviews different types of isomers found in sugars, including configurational isomers (enantiomers, diastereomers, epimers, and anomers) and conformational isomers (chair and boat forms). This section underscores how subtle differences in stereochemistry can have profound effects on glycan function and recognition. -

Monosaccharide Derivatives and Modifications:

Beyond the basic sugar units, the chapter discusses various chemical modifications of monosaccharides, such as oxidation, phosphorylation, amination, acetylation, lactone formation, and complex condensation reactions that lead to the formation of important derivatives like sialic acids. These modifications are critical in determining the biological roles and properties of glycans.

Overall, this chapter lays a foundation for understanding the intricate world of carbohydrate biochemistry by examining the molecular structures, stereochemical variations, and modifications that contribute to the functional complexity of glycans in biological systems.