Section 21.8: T-Cell Receptors (TCR) and Helper T Cells

- Page ID

- 146455

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)T-Cell Receptors

For both helper T cells and cytotoxic T cells, activation is a complex process that requires the interactions of multiple molecules and exposure to cytokines. The T-cell receptor (TCR) is involved in the first step of pathogen epitope recognition during the activation process.

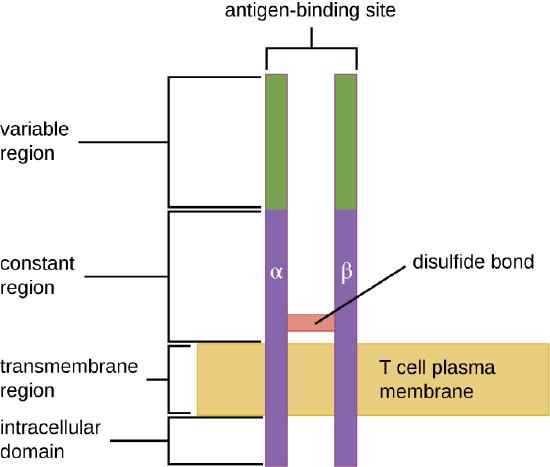

The TCR comes from the same receptor family as the antibodies IgD and IgM, the antigen receptors on the B cell membrane surface, and thus shares common structural elements. Similar to antibodies, the TCR has a variable regionand a constant region, and the variable region provides the antigen-binding site (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). However, the structure of TCR is smaller and less complex than the immunoglobulin molecules (Figure 18.1.4). Whereas immunoglobulins have four peptide chains and Y-shaped structures, the TCR consists of just two peptide chains (α and β chains), both of which span the cytoplasmic membrane of the T cell.

TCRs are epitope-specific, and it has been estimated that 25 million T cells with unique epitope-binding TCRs are required to protect an individual against a wide range of microbial pathogens. Because the human genome only contains about 25,000 genes, we know that each specific TCR cannot be encoded by its own set of genes. This raises the question of how such a vast population of T cells with millions of specific TCRs can be achieved. The answer is a process called genetic rearrangement, which occurs in the thymus during the first step of thymic selection.

The genes that code for the variable regions of the TCR are divided into distinct gene segments called variable (V), diversity (D), and joining (J) segments. The genes segments associated with the α chain of the TCR consist 70 or more different Vα segments and 61 different Jα segments. The gene segments associated with the β chain of the TCR consist of 52 different Vβ segments, two different Dβ segments, and 13 different Jβ segments. During the development of the functional TCR in the thymus, genetic rearrangement in a T cell brings together one Vα segment and one Jα segment to code for the variable region of the α chain. Similarly, genetic rearrangement brings one of the Vβ segments together with one of the Dβ segments and one of thetJβ segments to code for the variable region of the β chain. All the possible combinations of rearrangements between different segments of V, D, and J provide the genetic diversity required to produce millions of TCRs with unique epitope-specific variable regions.

- What are the similarities and differences between TCRs and immunoglobulins?

- What process is used to provide millions of unique TCR binding sites?

Activation and Differentiation of Helper T Cells

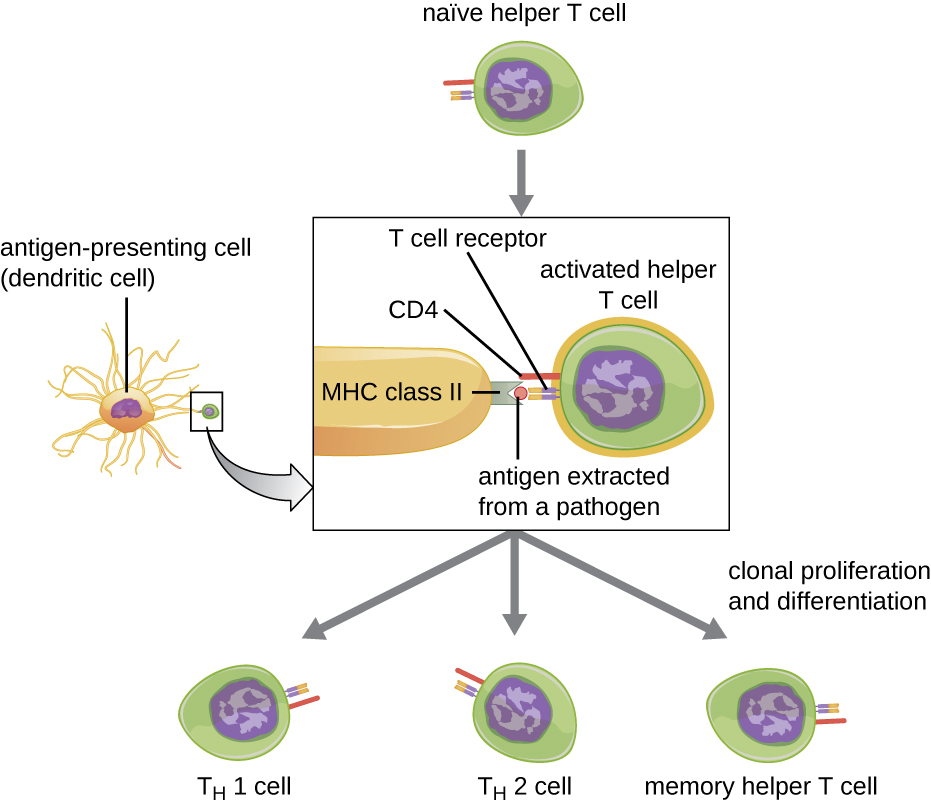

Helper T cells can only be activated by APCs presenting processed foreign epitopes in association with MHC II. The first step in the activation process is TCR recognition of the specific foreign epitope presented within the MHC II antigen-binding cleft. The second step involves the interaction of CD4 on the helper T cell with a region of the MHC II molecule separate from the antigen-binding cleft. This second interaction anchors the MHC II-TCR complex and ensures that the helper T cell is recognizing both the foreign (“nonself”) epitope and “self” antigen of the APC; both recognitions are required for activation of the cell. In the third step, the APC and T cell secrete cytokines that activate the helper T cell. The activated helper T cell then proliferates, dividing by mitosis to produce clonal naïve helper T cells that differentiate into subtypes with different functions (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Activated helper T cells can differentiate into one of four distinct subtypes, summarized in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\). The differentiation process is directed by APC-secreted cytokines. Depending on which APC-secreted cytokines interact with an activated helper T cell, the cell may differentiate into a T helper 1 (TH1) cell, a T helper 2 (TH2) cell, or a memory helper T cell. The two types of helper T cells are relatively short-lived effector cells, meaning that they perform various functions of the immediate immune response. In contrast, memory helper T cells are relatively long lived; they are programmed to “remember” a specific antigen or epitope in order to mount a rapid, strong, secondary response to subsequent exposures.

TH1 cells secrete their own cytokines that are involved in stimulating and orchestrating other cells involved in adaptive and innate immunity. For example, they stimulate cytotoxic T cells, enhancing their killing of infected cells and promoting differentiation into memory cytotoxic T cells. TH1 cells also stimulate macrophages and neutrophils to become more effective in their killing of intracellular bacteria. They can also stimulate NK cells to become more effective at killing target cells.

TH2 cells play an important role in orchestrating the humoral immune response through their secretion of cytokines that activate B cells and direct B cell differentiation and antibody production. Various cytokines produced by TH2 cells orchestrate antibody class switching, which allows B cells to switch between the production of IgM, IgG, IgA, and IgE as needed to carry out specific antibody functions and to provide pathogen-specific humoral immune responses.

A third subtype of helper T cells called TH17 cells was discovered through observations that immunity to some infections is not associated with TH1 or TH2 cells. TH17 cells and the cytokines they produce appear to be specifically responsible for the body’s defense against chronic mucocutaneous infections. Patients who lack sufficient TH17 cells in the mucosa (e.g., HIV patients) may be more susceptible to bacteremia and gastrointestinal infections.1

| Subtype | Functions |

|---|---|

| TH1 cells | Stimulate cytotoxic T cells and produce memory cytotoxic T cells |

| Stimulate macrophages and neutrophils (PMNs) for more effective intracellular killing of pathogens | |

| Stimulate NK cells to kill more effectively | |

| TH2 cells | Stimulate B cell activation and differentiation into plasma cells and memory B cells |

| Direct antibody class switching in B cells | |

| TH17 cells | Stimulate immunity to specific infections such as chronic mucocutaneous infections |

| Memory helper T cells | “Remember” a specific pathogen and mount a strong, rapid secondary response upon re-exposure |

Key Concepts and Summary

- Immature T lymphocytes are produced in the red bone marrow and travel to the thymus for maturation.

- Thymic selection is a three-step process of negative and positive selection that determines which T cells will mature and exit the thymus into the peripheral bloodstream.

- Central tolerance involves negative selection of self-reactive T cells in the thymus, and peripheral toleranceinvolves anergy and regulatory T cells that prevent self-reactive immune responses and autoimmunity.

- The TCR is similar in structure to immunoglobulins, but less complex. Millions of unique epitope-binding TCRs are encoded through a process of genetic rearrangement of V, D, and J gene segments.

- T cells can be divided into three classes—helper T cells, cytotoxic T cells, and regulatory T cells—based on their expression of CD4 or CD8, the MHC molecules with which they interact for activation, and their respective functions.

- Activated helper T cells differentiate into TH1, TH2, TH17, or memory T cell subtypes. Differentiation is directed by the specific cytokines to which they are exposed. TH1, TH2, and TH17 perform different functions related to stimulation of adaptive and innate immune defenses. Memory T cells are long-lived cells that can respond quickly to secondary exposures.

- Once activated, cytotoxic T cells target and kill cells infected with intracellular pathogens. Killing requires recognition of specific pathogen epitopes presented on the cell surface using MHC I molecules. Killing is mediated by perforin and granzymes that induce apoptosis.

- Superantigens are bacterial or viral proteins that cause a nonspecific activation of helper T cells, leading to an excessive release of cytokines (cytokine storm) and a systemic, potentially fatal inflammatory response.

Footnotes

- 1 Blaschitz C., Raffatellu M. “Th17 cytokines and the gut mucosal barrier.” J Clin Immunol. 2010 Mar; 30(2):196-203. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9368-7.