5.2: Comparing Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells

- Page ID

- 68560

Cells fall into one of two broad categories: prokaryotic and eukaryotic. The predominantly single-celled organisms of the domains Bacteria and Archaea are classified as prokaryotes (pro– = before; –karyon– = nucleus). Animal cells, plant cells, fungi, and protists are eukaryotes (eu– = true).

All cells share four common components: 1) a plasma membrane, an outer covering that separates the cell’s interior from its surrounding environment; 2) cytoplasm, consisting of a gel-like region within the cell in which other cellular components are found; 3) DNA, the genetic material of the cell; and 4) ribosomes, particles that synthesize proteins.

Components of Prokaryotic Cells

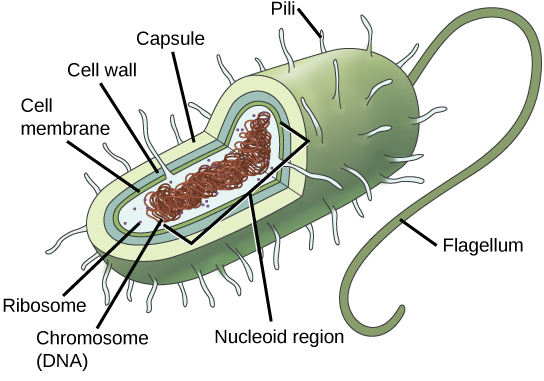

Prokaryotes differ from eukaryotic cells in several important ways. A prokaryotic cell is a simple, single-celled (unicellular) organism that lacks a nucleus, or any other membrane-bound organelle. We will shortly come to see that this is significantly different in eukaryotes. Prokaryotic DNA is found in the central part of the cell: a darkened region called the nucleoid (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Unlike Archaea and eukaryotes, bacteria have a cell wall made of peptidoglycan, comprised of sugars and amino acids, and many have a polysaccharide (carbohydrate) capsule (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The cell wall acts as an extra layer of protection, helps the cell maintain its shape, and prevents dehydration. The capsule enables the cell to attach to surfaces in its environment. Some prokaryotes have flagella, pili, or fimbriae. Flagella are used for locomotion, while most pili are used to exchange genetic material during a type of reproduction called conjugation.

Components of Eukaryotic Cells

In nature, the relationship between form and function is apparent at all levels, including the level of the cell, and this will become clear as we explore eukaryotic cells. The principle “form follows function” is found in many contexts. For example, birds and fish have streamlined bodies that allow them to move quickly through the medium in which they live, be it air or water. It means that, in general, one can deduce the function of a structure by looking at its form, because the two are matched.

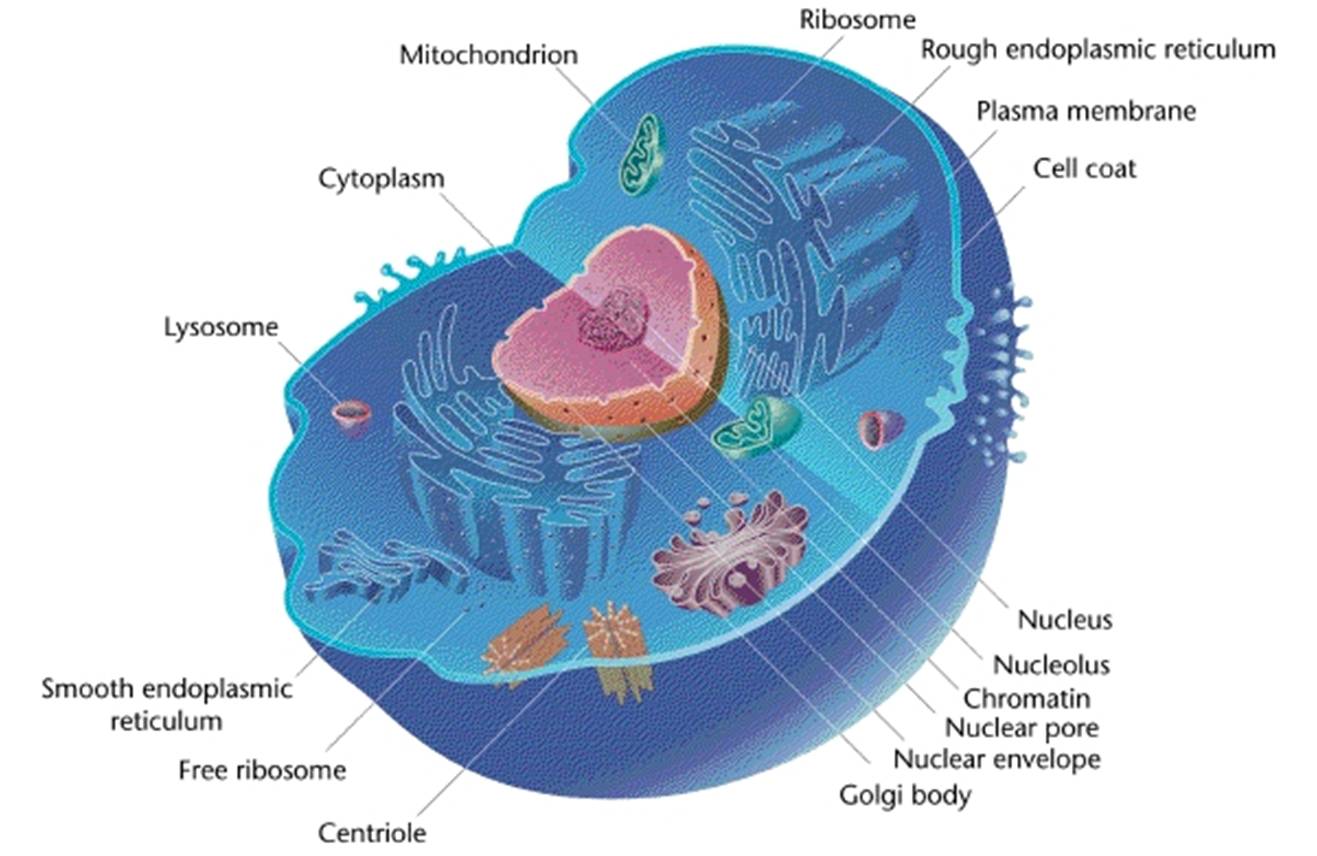

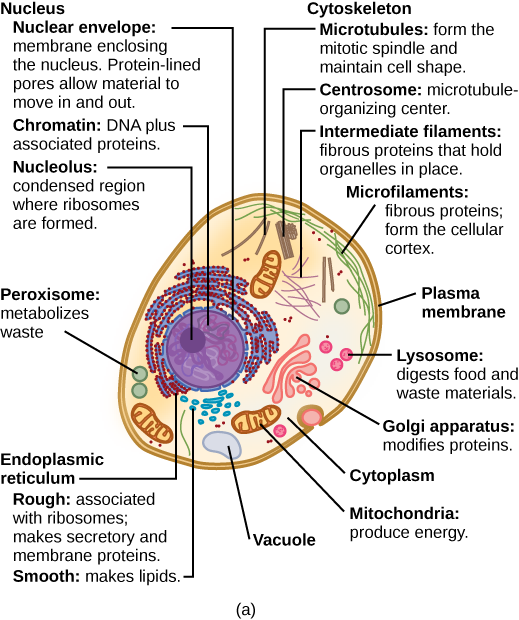

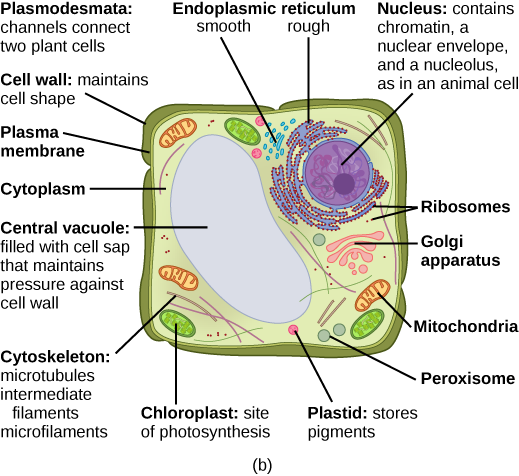

A eukaryotic cell is a cell that has a membrane-bound nucleus and other membrane-bound compartments or sacs, called organelles, which have specialized functions. The rest of this chapter will discuss functions of the various organelles. The word eukaryotic means “true kernel” or “true nucleus,” alluding to the presence of the membrane-bound nucleus in these cells. The word “organelle” means “little organ,” and, as already mentioned, organelles have specialized cellular functions, just as the organs of your body have specialized functions.

Both animals and plants are eukaryotes. Despite their fundamental similarities, there are some striking differences between animal and plant cells. Animal cells have centrioles, centrosomes (discussed under the cytoskeleton), and lysosomes, whereas plant cells do not. Plant cells have a cell wall, chloroplasts, plasmodesmata, and plastids used for storage, and a large central vacuole, whereas animal cells do not.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

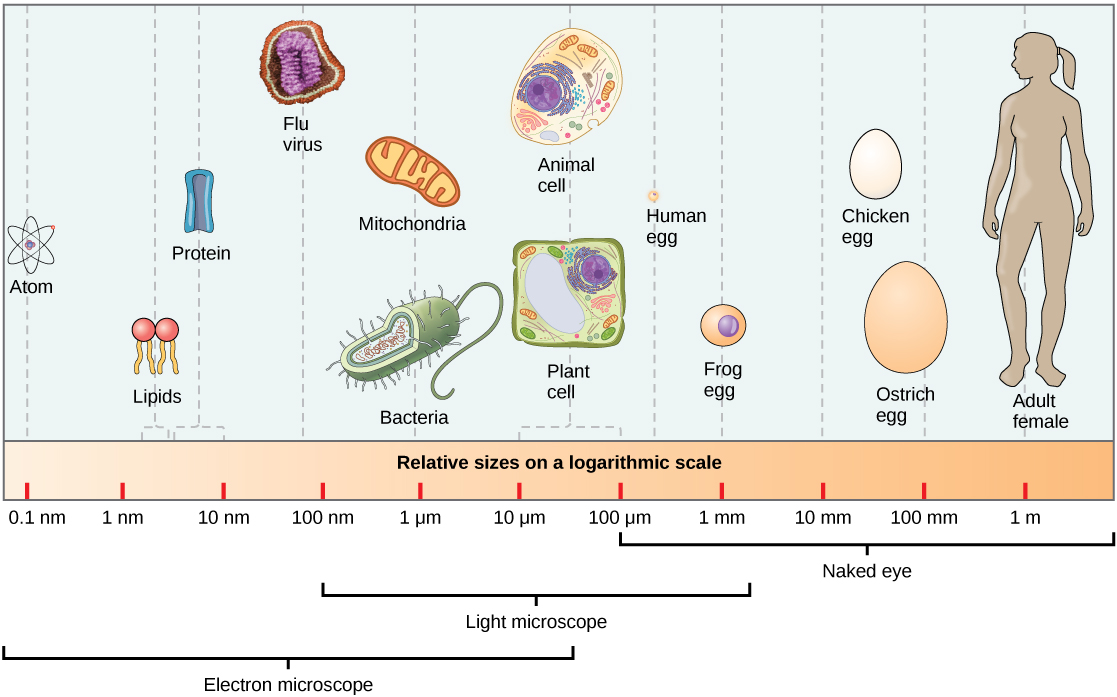

Cell Size

At 0.1–5.0 μm in diameter, prokaryotic cells are significantly smaller than eukaryotic cells, which have diameters ranging from 10–100 μm (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The small size of prokaryotes allows ions and organic molecules that enter them to quickly spread to other parts of the cell. Similarly, any wastes produced within a prokaryotic cell can quickly move out. However, larger eukaryotic cells have evolved different structural adaptations to enhance cellular transport. Indeed, the large size of these cells would not be possible without these adaptations. In general, cell size is limited because volume increases much more quickly than does cell surface area. As a cell becomes larger, it becomes more and more difficult for the cell to acquire sufficient materials to support the processes inside the cell, because the relative size of the surface area across which materials must be transported declines.

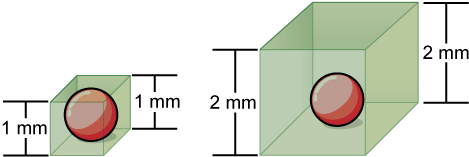

Small size, in general, is necessary for all cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic. Let’s examine why that is so. First, we’ll consider the area and volume of a typical cell. Not all cells are spherical in shape, but most tend to approximate a sphere. You may remember from your geometry course that the formula for the surface area of a sphere is 4πr2, while the formula for its volume is 4πr3/3. Thus, as the radius of a cell increases, its surface area increases as the square of its radius, but its volume increases as the cube of its radius (much more rapidly). Therefore, as a cell increases in size, its surface area-to-volume ratio decreases. This same principle would apply if the cell had the shape of a cube (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). If the cell grows too large, the plasma membrane will not have sufficient surface area to support the rate of diffusion required for the increased volume. In other words, as a cell grows, it becomes less efficient. One way to become more efficient is to divide; another way is to develop organelles that perform specific tasks. These adaptations lead to the development of more sophisticated cells called eukaryotic cells.

Query \(\PageIndex{3}\)

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

Text adapted from: OpenStax, Concepts of Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 18, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/b3c1e1d2-839...9a8aafbdd@9.10