17.1C: Biomes

- Page ID

- 5816

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A biome is a large, distinctive complex of plant communities created and maintained by climate.

How many biomes are there?

A study published in 1999 concluded that there are 150 different "ecoregions" in North America alone. But I shall cast my lot with the "lumpers" rather than the "splitters" and lump these into 8 biomes:

- tundra

- taiga

- temperate deciduous forest

- scrub forest (called chaparral in California)

- grassland

- desert

- tropical rain forest

- temperate rain forest

The figure shows the distribution of these 8 biomes around the world. A number of climatic factors interact in the creation and maintenance of a biome. Where precipitation is moderately abundant — 40 inches (about 1 m) or more per year — and distributed fairly evenly throughout the year, the major determinant is temperature. It is not simply a matter of average temperature, but includes such limiting factors as whether it ever freezes or length of the growing season. If there is ample rainfall, we find 4 characteristic biomes as we proceed from the tropics (high temperatures) to the extreme latitudes (low temperatures). In order, they are:

- tropical rain forest or jungle

- temperate deciduous forest

- taiga

- tundra

Tropical Rain Forest

In the Western Hemisphere, the tropical rain forest reaches its fullest development in the jungles of Central and South America.

- The trees are very tall and of a great variety of species.

- One rarely finds two trees of the same species growing close to one another.

- The vegetation is so dense that little light reaches the forest floor.

- Most of the plants are evergreen, not deciduous.

- The branches of the trees are festooned with vines and epiphytes (see the photo taken in the Luquillo National Forest of Puerto Rico).

Epiphytes are plants that live perched on sturdier plants. They do not take nourishment from their host as parasitic plants do. Because their roots do not reach the ground, they depend on the air to bring them moisture and inorganic nutrients. Many orchids and many bromeliads (members of the pineapple family like "Spanish moss") are epiphytes.

The lushness of the tropical rain forest suggests a high net productivity, but this is illusory. Many of the frequent attempts to use the tropical rain forest for conventional crops have been disappointing. Two problems:

- The high rainfall leaches soil minerals below the reach of plant roots.

- The warmth and moisture cause rapid decay so little humus is added to the soil.

The tropical rain forest exceeds all the other biomes in the diversity of its animals as well as plants. Most of the animals - mammals and reptiles, as well as birds and insects live in the trees. The closest thing to a tropical rain forest in the continental United States are the little wooded "islands" found scattered through the Everglades in the southern tip of Florida. Their existence depends on the fact that it never freezes, and they often escape the fires that periodically sweep the Everglades.

Temperate Deciduous Forest

This biome occupies the eastern half of the United States and a large portion of Europe. It is characterized by:

- hardwood trees (e.g., beech, maple, oak, hickory) which

- are deciduous; that is, shed their leaves in the autumn.

- The number of different species is far more limited than in the jungle.

- Large stands dominated by a single species are common.

- Deer, raccoons, and salamanders are characteristic inhabitants.

- During the growing season, this biome can be quite productive in both natural and agricultural ecosystems.

The photo (by Dick Morton) shows a view of this biome in Maine in the autumn.

Taiga

Fig.17.1.3.4 Taiga

The taiga is named after the biome in Russia.

- It is a land dominated by conifers, especially spruces and firs.

- It is dotted with lakes, bogs, and marshes.

- It is populated by an even more limited variety of plants and animals than is the temperate deciduous forest.

- In North America, the moose is such a typical member that it has led to the name: "spruce-moose" biome.

- Before the long, snowy winter sets in, many of the mammals hibernate, and many of the birds migrate south.

- Although the long days of summer permit plants to grow luxuriantly, net productivity is low.

The photo (courtesy of Dr. Benjamin Dane of Tufts University) shows the "spruce-moose" biome in British Columbia.

Tundra

At extreme latitudes, the trees of the taiga become stunted by the harshness of the subarctic climate. Finally, they disappear leaving a land of bogs and lakes.

- The climate is so cold in winter that even the long days of summer are unable to thaw the permafrost beneath the surface layers of soil.

- Sphagnum moss, a wide variety of lichens, and some grasses and fast-growing annuals dominate the landscape during the short growing season.

- Caribou feed on this growth as do vast numbers of insects.

- Swarms of migrating birds, especially waterfowl, invade the tundra in the summer to raise their young, feeding them on a large variety of aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates.

- As the brief arctic summer draws to a close, the birds fly south, and

- all but a few of the permanent residents, in one way or another, prepare themselves to spend the winter in a dormant state.

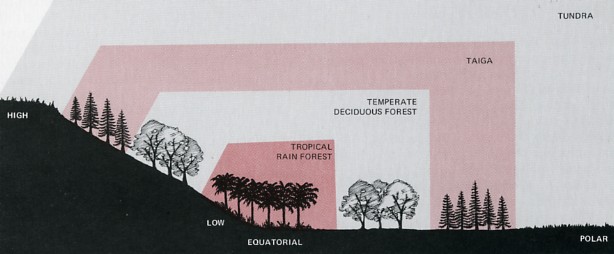

Biomes established by altitude

Temperature is the major influence on the biomes discussed above. Because temperatures decline with altitude as well as latitude, similar biomes exist on mountains even when they are at low latitudes. As a rule of thumb, a climb of 1000 feet (about 300 m) is equivalent in changed flora and fauna to a trip northward of some 600 miles (966 km).

The photo is of alpine tundra at 12,000 feet (3,658 m) in the Rocky Mountains.

Field studies in various parts of the Northern Hemisphere have shown that in recent decades many species of animals and plants have

- shifted their ranges farther north (averagiing 16.9 kilometers per decade)

- shifted their ranges higher in the mountains (averaging 11.0 meters per decade)

These observations add to the growing body of evidence that global warming is affecting a broad assortment of living things.

Biomes established by rainfall

The other major biomes are controlled not so much by temperature but by the amount and seasonal distribution of rainfall.

The prevailing winds in the western half of North America blow in from the Pacific laden with moisture. Each time this air rises up from the western slopes of, successively, the Coast Ranges, the Sierras and Cascades, and finally the Rockies, it expands and cools. Its moisture condenses to rain or snow, which drenches the mountain slopes beneath. When the air reaches the eastern slopes, it is relatively dry, and much less precipitation falls. How much falls and when determine whether the biome will be

- temperate rain forest

- grassland

- desert or

- chaparral

Temperate Rain Forest

The temperate rain forest combines high annual rainfall with a temperate climate. The Olympic Peninsular in North America is a good example. An annual rainfall of as much as 150 inches (381 cm) produces a lush forest of conifers.

Grasslands

Grasslands are also known as prairie or plains. The annual precipitation in the grasslands averages 20 inches (~51 cm) per year. A large proportion of this falls as rain early in the growing season. This promotes a vigorous growth of perennial grasses and herbs, except along river valleys - is barely adequate for the growth of forests. The photo shows grassland in the Badlands National Monument in South Dakota.

Fire is probably the factor that tips the balance from forest to grasslands. Fires set by lightning and by humans regularly swept the plains in earlier times. Thanks to their underground stems and buds, perennial grasses and herbs are not harmed by fires that destroy most shrubs and trees.

The abundance of grass for food, coupled with the lack of shelter from predators, produces similar animal populations in grasslands throughout the world. The dominant vertebrates are swiftly-moving, herbivorous ungulates. In North America, bison and antelope were conspicuous members of the grassland fauna before the coming of white settlers. Now the level grasslands supply corn, wheat, and other grains, and the hillier areas support domesticated ungulates: cattle and sheep.

When cultivated carefully, the grassland biome is capable of high net productivity. A major reason: rainfall in this biome never leaches soil minerals below the reach of the roots of crop plants.

Desert

Annual rainfall in the desert is less than 10 inches (25 cm) and, in some years, may be zero. Because of the extreme dryness of the desert, its colonization is limited to

- plants such as cacti, sagebrush, and mesquite that have a number of adaptations that conserve water over long periods

- fast-growing annuals whose seeds can germinate, develop to maturity, flower, and produce a new crop of seeds all within a few weeks following a rare, soaking rain.

The photo shows the desert in the Anza-Borego park in southern California.

Many of the animals in the desert (mammals, lizards and snakes, insects, and even some birds) are adapted for burrowing to escape the scorching heat of the desert sun. Many of them limit their forays for food to the night. The net productivity of the desert is low. High productivity can sometimes be achieved with irrigation, but these gains are often only temporary. The high rates of evaporation cause minerals to accumulate near the surface and soon their concentration may reach levels toxic to plants.

Chaparral

The annual rainfall in the chaparral biome may reach 20–30 inches (64–76 cm), but in contrast to the grasslands, almost all of this falls in winter. Summers are very dry and all the plants - trees, shrubs, and grasses - are more or less dormant then.

The chaparral is found in California. (The photo shows the chaparral-clad foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California.) Similar biomes (with other names, such as scrub forest), are found around much of the Mediterranean Sea and along the southern coast of Australia.

The trees in the chaparral are mostly oaks, both deciduous and evergreen. Scrub oaks and shrubs like manzanita and the California lilac (not a relative of the eastern lilac) form dense, evergreen thickets. All of these plants are adapted to drought by such mechanisms as waxy, waterproof coatings on their leaves. The chaparral has many plants brought to it from similar biomes elsewhere. Vineyards, olives, and figs flourish just as they do in their native Mediterranean biome. So, too, do eucalyptus trees transplanted from the equivalent biome in Australia.

Contributors and Attributions

John W. Kimball. This content is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) license and made possible by funding from The Saylor Foundation.