17.1: Digestion, Mobilization, and Transport of Fats

- Page ID

- 15025

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)-

Differentiate Sources and Roles of Fatty Acids:

- Explain the two primary sources of fatty acids—dietary (e.g., triacylglycerols from food) and de novo synthesis from acetyl-CoA—and describe their respective roles in energy production and membrane composition.

-

Describe Lipid Storage in Various Tissues:

- Compare the functions of white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT) in lipid storage and energy expenditure, including the roles of lipid droplets, hormone regulation, and the thermogenic protein uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1).

-

Outline Lipoprotein Structure and Classification:

- Summarize the structural organization of lipoproteins, emphasizing the single phospholipid monolayer, lipid core, and associated apolipoproteins.

- Classify lipoproteins by density (chylomicrons, VLDL, IDL, LDL, and HDL) and explain how differences in size, composition, and apolipoprotein content affect their function in lipid transport.

-

Explain the Role of Apolipoproteins in Lipid Transport:

- Describe the functions of key apolipoproteins (e.g., apoB100, apoB48, apoA-I, apoE, and apoA-IV) in stabilizing lipoprotein particles, mediating receptor interactions, and facilitating lipid exchange among particles.

- Discuss how structural features such as tandem amphiphilic helices contribute to the lipid-binding and membrane-associating properties of these proteins.

-

Understand the Mechanisms of Lipoprotein Assembly and Uptake:

- Illustrate how dietary lipids are hydrolyzed and reassembled into lipoproteins (e.g., chylomicrons and VLDL) in the intestine and liver, including the roles of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) and apolipoprotein processing.

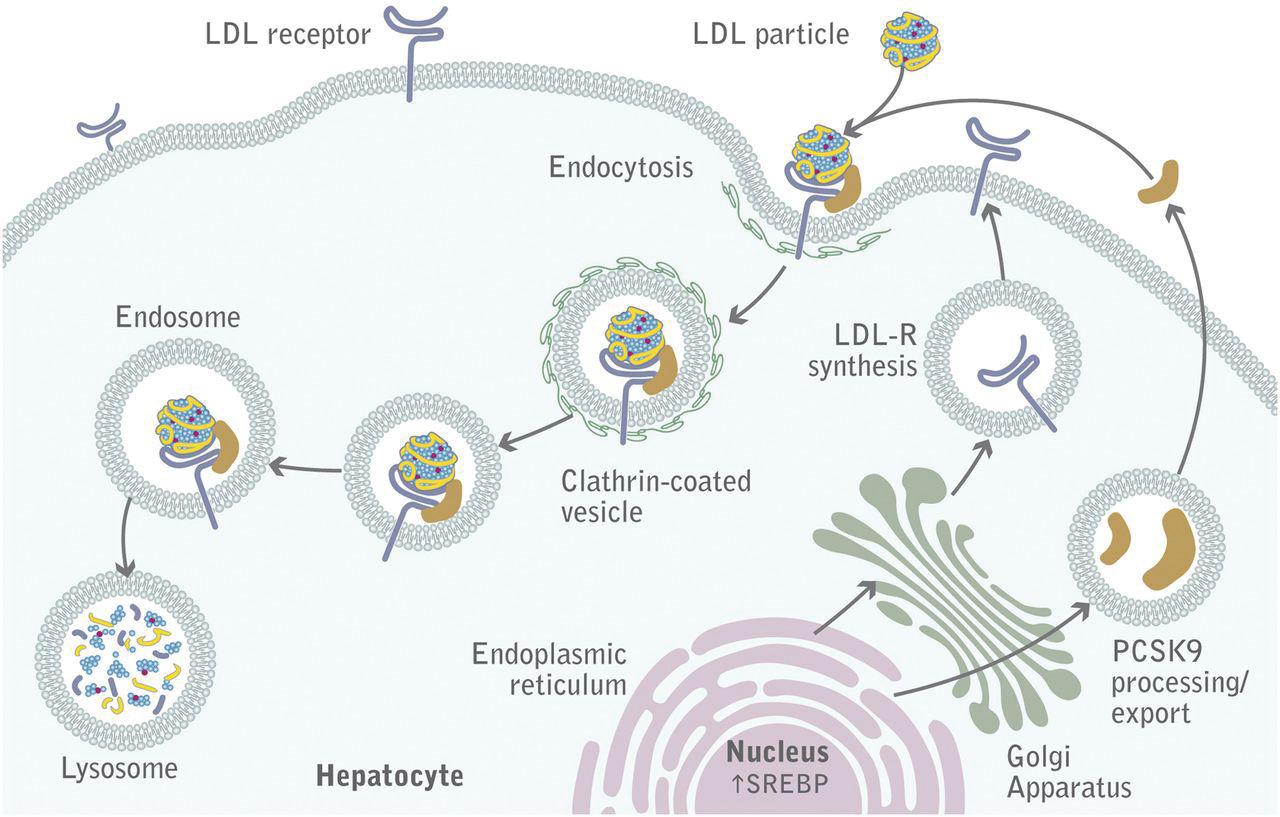

- Explain the receptor-mediated uptake of LDL via the LDL receptor, including the structural domains involved in ligand binding and the role of accessory proteins (e.g., PCSK9) in receptor recycling and degradation.

-

Describe the Function and Regulation of Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL):

- Detail how LPL, in association with GPIHBP1 and heparan sulfate, catalyzes the hydrolysis of TAGs in circulating chylomicrons and VLDL to release free fatty acids for uptake by tissues.

- Explain the structural features of LPL, including its catalytic triad, and how calcium ions stabilize its active dimeric form.

-

Examine Albumin’s Role in Fatty Acid Transport:

- Discuss how human serum albumin (HSA) binds multiple fatty acids and various small hydrophobic drugs, influencing their bioavailability and transport in the bloodstream.

-

Analyze the Impact of Lipoproteins on Cardiovascular Health:

- Compare the roles of LDL (and its variant Lp(a)) and HDL in cardiovascular risk, emphasizing how LDL levels are associated with atherogenesis, while HDL is involved in reverse cholesterol transport and is generally cardioprotective.

-

Evaluate the Effects of Lipid Remodeling Enzymes:

- Describe the function of enzymes such as lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP), and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) in the assembly, maturation, and remodeling of lipoproteins.

-

Integrate Metabolic Regulation with Hormonal Control:

- Summarize how hormonal states (e.g., fed vs. fasting) influence the balance between lipid storage and lipolysis in adipocytes and liver cells, including the roles of insulin, glucagon, and epinephrine.

-

Connect Structural Characteristics with Functional Outcomes:

- Utilize interactive molecular models to visualize and analyze the structural determinants of lipid-binding in apolipoproteins and the conformational properties of lipoprotein particles, linking these insights to their physiological functions and implications in diseases such as atherosclerosis.

By achieving these learning goals, students will develop a comprehensive understanding of how fatty acids and lipoproteins are processed, transported, and regulated in the body, and how these processes impact energy metabolism and cardiovascular health.

Introduction

This chapter will discuss the breakdown of fats to produce ATP. Most of the available chemical energy stored in fats is in the form of highly reduced fatty acids. One form of fatty acid-containing lipids comes from our diet, which includes triacylglycerols (TAGs) and membrane lipids. Fatty acids, mainly in TAGs, are moved in the circulation by large lipid-carrying vesicles called lipoproteins. Lipids can be imported into cells for storage and energy utilization.

Another source of fatty acids comes from those synthesized within cells from the small molecule acetyl-CoA. Fatty acids are synthesized by an enzyme complex called fatty acid synthase. This enzyme is most prevalent in adipose (fat) tissue and the liver. Additionally, it is highly expressed in the brain, lungs, and mammary glands.

TAGs, stored in lipid droplets, are found in most cells. The central tissue used for TAG storage is adipose (fat) tissue, whose volume consists primarily of lipid droplets. Given the large muscle tissue mass, a considerable amount of TAGs is stored as small lipid droplets in muscle cells. However, skeletal muscle cells don't synthesize fatty acids. They possess the genes for fatty acid synthase but do not transcribe them into RNA, so no enzyme is produced. They can, however, import them for catabolism. Muscle TAGs can be oxidized for energy, especially during endurance exercise.

TAGs are also stored in the liver in lipid droplets. The liver also assembles lipoproteins, which are then released into the bloodstream. Excess TAGs are stored in the liver in various diseases, including alcoholism and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which can progress into nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a much worse disease.

Two major forms of triacylglycerol-storing fat tissues exist: white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). The more abundant WAT stores triacylglycerols in a single large lipid droplet within the cell and releases fatty acids through processes controlled by the hormones insulin and epinephrine. This simple role can mask the fact that adipose tissue is a major player in the endocrine system, playing a crucial role in cell signaling and systemic control of metabolism. Adipose tissue releases the key hormones leptin and adipisin, which, in analogy to the hormones and signaling agents released by immune cells (cytokines, lymphokines), can be called adipokines. They also secrete other adipokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), adiponectin, and resistin.

In contrast, BAT specializes not in storing and releasing fatty acids but rather in oxidizing fatty acids in ways that maximize heat production, preventing hypothermia. They have multiple smaller lipid droplets, displaying a larger surface area for lipolysis, the hydrolytic cleavage of fatty acids from the TAGs. A particular mitochondrial protein, uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), is expressed in brown but not white adipocytes, allowing a "futile" metabolic cycle that leads to the dissipation of heat instead of ATP synthesis. The relative abundance of white and brown adipocytes is crucial in diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. BAT tissue is especially important for thermoregulation in small animals (and newborns). The surface area-to-volume ratio for smaller organisms is greater than that for larger animals, allowing for more efficient heat loss. The ratio of surface area AS per volume V for a sphere is given by:

\[\dfrac{\mathrm{SA}_{\text {sphere }}}{\mathrm{V}_{\text {sphere }}}=\dfrac{4 \pi \mathrm{r}^{2}}{\left(\dfrac{4}{3}\right) \pi \mathrm{r}^{3}} \nonumber \]

Let's assume an average large adipocyte is a sphere with a diameter of 100 μm. Compare this to a large sphere with a 100 times greater diameter (10,000 μm). The smaller sphere has 1/100 of the diameter but a surface area-to-volume ratio 100 times greater than that of the large sphere.

Just for fun: Many know the formula for the volume of a sphere:

\begin{equation}

V(r)=\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3

\end{equation}

The derivative of the volume with respect to the radius r, dV/dr, gives the volume of an infinitesimal shell around the sphere. Here is the relevant equation:

\begin{equation}

\frac{d V}{d r}=\frac{d}{d r}\left(\frac{4}{3} \pi r^3\right)=4 \pi r^2

\end{equation}

The area of the infinitesimal sphere is:

\begin{equation}

A=4 \pi r^2

\end{equation}

The volume of the infinitesimal sphere is the above equation multiplied by dr! This is a cool application of first-semester calculus!

An intermediate type of fat tissue consists of "bright" adipocytes. White adipocytes can be coaxed to differentiate into beige and brown cells, which could be a potential treatment for obesity.

In this chapter, we will follow the fate of fatty acids from dietary lipids cleaved from TAGs, loaded into chylomicrons, a lipoprotein assembled in the small intestine, secreted into the circulation, and taken up by the liver. The liver can store the incoming fatty acids in TAGs or release them back into the circulation in the form of another lipoprotein, very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). Circulating VLDL can exchange lipids with other circulating lipoproteins. Lipoproteins deliver fatty acids to cells after interaction with the cell surface of target cells. The fatty acids move into the cell through either the cleavage of TAGs by cell membrane-associated enzyme lipase, followed by fatty acid uptake, or by endocytosis of lipoproteins into the cells.

Lipoproteins

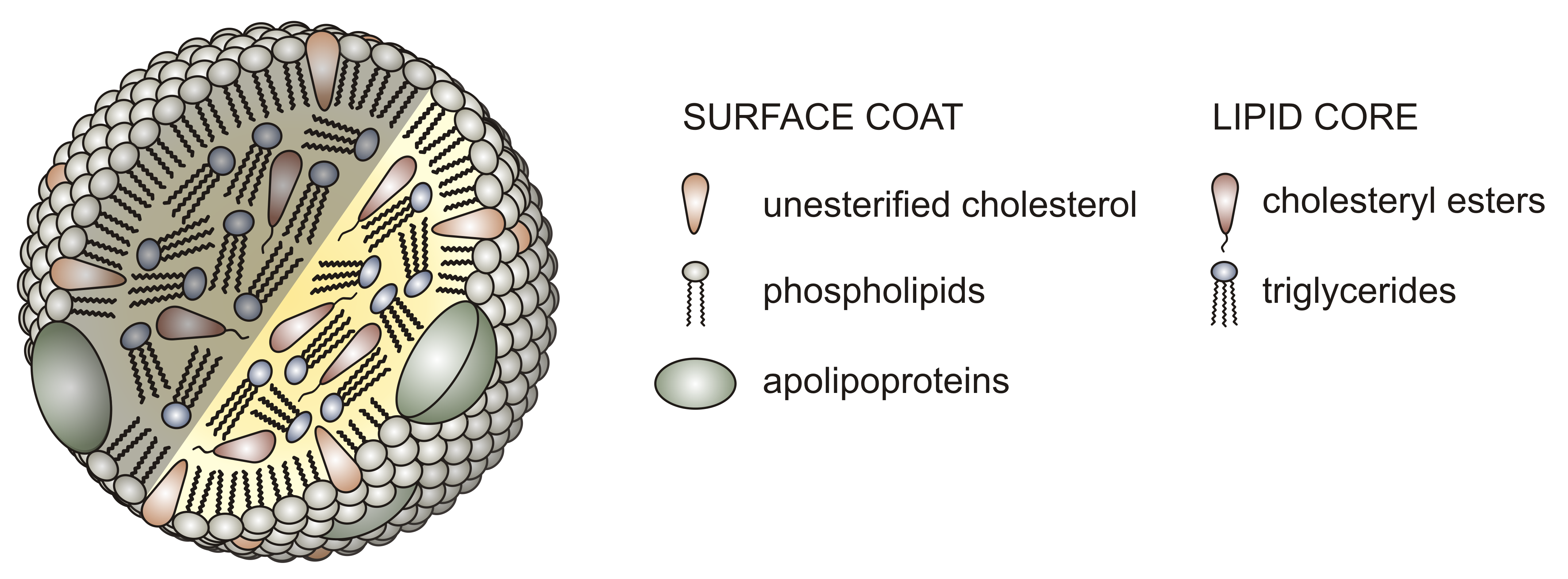

Before examining the individual steps in lipid processing, let's first consider the various lipoproteins. These large vesicular structures transport fats, which are very insoluble molecules, in the circulation. Unlike normal liposomes or vesicles with a lipid bilayer surrounding an interior aqueous compartment, lipoproteins have only a single monolayer of phospholipids encapsulating a nonaqueous interior filled with TAGs, cholesterol, and cholesterol esters. The protein part of the lipoprotein consists of one or several proteins bound on the outside of the particle. The proteins help solubilize the lipoprotein, confine its size, and prevent the aggregation of lipoproteins, which would pose a health risk. The structure of a typical lipoprotein is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Lipoproteins are classified based on density. The lowest density one, chylomicrons, is the largest and contains the most lipids (mostly triacylglycerols, or TAGs) in its interior compartment. Very large density lipoproteins (VLDL), intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL), low density lipoproteins (LDL), and high density lipoproteins (HDL) have decreasing size, fewer encapsulated lipids, and increasing density. The relative sizes are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Lipoproteins (except chylomicrons) can be classified as nanoparticles, which typically vary in size from 1 to 100 nm. Larger lipoproteins and chylomicrons form emulsions in the blood, much as milk (also cloudy) is an emulsion of lipid/protein particles. The serum of people with high levels of lipids (hyperlipidemia) can look milky white, especially after eating foods rich in TAGs, when levels of chylomicrons are very high. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the blood of a patient with hyperlipidemia after the addition of EDTA (which binds Ca2+ and prevents clotting) that has settled (without centrifugation). The milky white plasma on top (lower density) likely has high concentrations of chylomicrons and/or LDL. The lower layer primarily consists of red blood cells.

No X-ray structures of lipoproteins are available. However, the structure of a nascent HDL particle (3k2s) has been determined using small-angle neutron scattering. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of it.

The major protein in HDL, a lipoprotein that protects against cardiovascular disease, is apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I). Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows that it adopts an antiparallel double superhelix as it wraps around the nascent HDL. The more hydrophobic surfaces of apo A-I are oriented inward, allowing interactions with hydrophobic lipids in the core. It is probably prototypical for nascent lipoproteins. It will give you an idea of how proteins wrap around the outside of the particle. Mature lipoproteins are most likely spherical. This nascent HDL in the model contains 200 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholines (POPC) molecules, 20 cholesterol, and a single copy of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I).

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) below shows a cartoon image of VLDL, assembled from lipids synthesized/taken up by and released from the liver, and chylomicrons, assembled from dietary fats and released from enterocytes in the small intestine (size of the lipoproteins is not to scale). VLDL has one copy of Apo B-100, while chylomicrons have one copy of Apo B-48.

All lipoproteins, except HDL, are members of the Beta-lipoprotein family as they contain an apo-B protein. The liver synthesizes apo B100, which becomes a permanent part of VLDL (i.e, it is not exchangeable with other lipoproteins) and its metabolic derivatives, so any lipoprotein containing apo B100 arose from the liver. Other proteins on lipoproteins are exchangeable. In contrast, enterocytes in the small intestine produce apo B-48 (48% the size of apo B100), so this protein marks the lipoproteins (chylomicrons and chylomicron remnants) assembled in the small intestine. Apo B100 has over 4500 amino acids and a molecular mass of 555kDa. The gene for intestinal apo B48 is the same as that for apo B100, except that it contains a premature stop codon, resulting in a shorter, truncated apo B-48.

Apoproteins bind to specific receptors on cells, allowing the uptake of the lipoprotein. For example, the LDL receptors bind to the apo B-100 protein on a region removed (by proteolytic processing) from the apo B48 protein of chylomicrons. They also bind ApoE, which is predominantly found on HDL and VLDL, but some are also present in LDL. The LDL receptors are also called the ApoB/ApoE receptor.

Over 90% of the apoB-containing particles in circulation are LDL. In addition, chylomicrons are present in circulation only after eating. Some apoproteins can act as cofactors and inhibitors for lipoprotein processing.

High concentrations of LDL are associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Chylomicron levels, given their transient and lower concentration levels, do not pose a health risk unless the enzyme required to remove fatty acids from them, lipoprotein lipase, is missing or defective, or if another apoprotein component, apo CII, which mediates the interaction with lipoprotein lipase, is missing. LDL-C (a term used to describe the total cholesterol in LDL particles, which is routinely measured in clinical labs) can be lowered by a healthy diet centered around plant foods. Drugs like statins decrease endogenous cholesterol synthesis, lower LDL levels, and decrease cardiovascular risk.

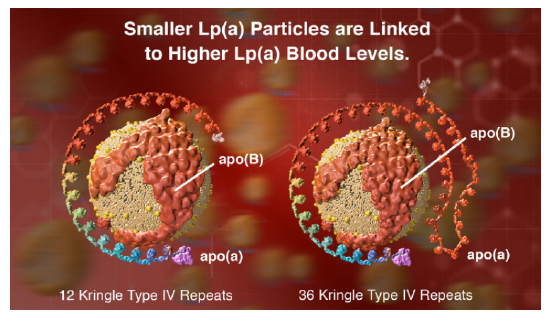

However, another protein, lipoprotein, also called Lp(a) or LP "little a," is an independent cardiovascular risk factor. Its blood concentration is regulated by genetics and not by diet. In addition to apo B100, these particles contain apo (a), a protein with a unique repeating structure (up to 40 times) called a kringle, which is also found in some proteins involved in the blood coagulation system. People whose genes encode apo (a) with the fewest number of kringles express lots of that protein, and their Lp(a) particles are smaller. This confers a greater cardiovascular risk compared to those expressing proteins with many kringle domains. Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) (from Amgen) shows models of Lp(a) with different numbers of repeating kringle (kinked) domains.

From a biochemical perspective, exploring the differences in apolipoprotein binding to single-leaflet-encapsulated lipid nanoparticles is interesting compared to the interaction of peripheral and integral membrane proteins with intact bilayers (which have two leaflets, as studied in Chapter 12.1). As mentioned above, the more nonpolar surfaces of apo AI in HDL are oriented inward toward the nonpolar lipid core. Presumably, apo B proteins in chylomicrons and LDL also wrap around the entire lipid surface.

HDL's major organizing scaffolding protein is apoA-I (see iCn3D model above). It presumably plays a role similar to apoB in chylomicrons and LDL, but it is exchangeable. (Note: ApoA-I is also found in chylomicrons.) It is also a cofactor for the enzyme lecithin:cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT), which converts free cholesterol in the single bilayer into esterified cholesterol esters within HDL. In its apo-form, it also interacts with the cell surface transporter ATP-binding cassette A1 (ABCA1), which plays a role in assembling HDL particles. HDL also has apoC and apoE proteins, all of which are exchangeable.

Given their heterogeneity and size, it is difficult to determine the structure of lipoproteins. Apolipoproteins have hydrophobic surfaces that promote self-association and aggregation. Apolipoproteins in the A, C, and E classes have repeating amphiphilic helices that embed to some degree in the lipid particles. In addition, the proteins exhibit significant disorder and can adopt multiple bound conformations.

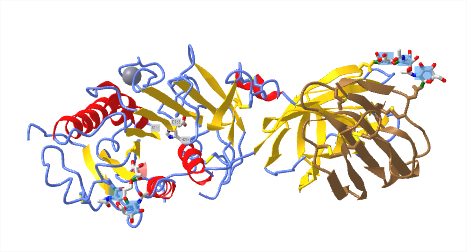

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the AlphaFold predicted structure of human Apo E (P02649) (P06727)

The blue cartoon color represents high certainty in the AlphFold predicted structure, while yellow to orange represents low certainty. The hydrophobic side chains are shown as sticks, helping illustrate the structure's amphiphilic nature.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the AlphaFold predicted structure of human Apo A4 (P02649)

The blue cartoon color represents high certainty in the AlphFold predicted structure, while yellow to orange represents low certainty. The hydrophobic side chains are shown as sticks. Again, note the amphiphilic nature of the structure.

The exchangeable apolipoproteins have similar genetic sequences (four exons and three introns) and similar amino acid sequences. They have 11-mer amino acid tandem repeats, and some (A-I, A-IV) have 22-mer tandem repeats. These repeats form amphiphilic helices as determined by sequence analysis. The first amino acid in the amphiphilic helix is often positively charged, and a negative one is often found in the middle. Proline, a helix breaker, is often but not always found between the helices.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows the primary sequence of apoA-I. An 11-mer repeat is highlighted in yellow. The other highlighted stretches (in different colors) are 22-mer repeats. Note that the repeats are not of identical sequences but rather of sequences that can form amphiphilic helices (i.e., secondary structure repeats).

The bottom part of Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)shows a helical wheel projection (using Heliquest) of the red-highlighted 22-mer repeat. The arrow shows the hydrophobic moment with the arrowhead pointing to the more nonpolar face. The particular amphiphilic helix shown may or may not facilitate the binding of the bound conformation of the protein.

The relative areas of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic faces in the amphipathic helices influence the lipid-associating properties of the exchangeable apolipoproteins. The arrangement of tandem repeating amphipathic helices is another factor that might influence the lipid-binding ability of exchangeable apolipoproteins.

Actual amphiphilic helices would bind to the membrane in a parallel fashion, with the nonpolar face anchoring the protein to the lipid surface. Other experimental techniques are used to study how a peptide or protein that can form amphiphilic helices interacts with the lipid surface. These include site-directed mutagenesis studies coupled with spectroscopic (CD, fluorescence) and binding assay methods (using liposomes).

The properties of a membrane-bound amphiphilic helix are affected by the exact size and distribution of the polar/charged and nonpolar side chains. On binding, they sense or cause membrane curvature, interact with specific lipids, and stabilize specific membrane conformations (such as spherical for lipoproteins). Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) shows how different proteins with amphiphilic membranes interact with membrane surfaces.

A key point to note is the large conformational changes that occur as the protein or parts of it go from the free, more disordered state to the bound state with lipid-associating amphiphilic helices. The following proteins are depicted in the figure.

- The peroxisomal membrane protein Pex11 amphiphilic helix distorts the membrane;

- ARF1 is a small G protein in which only the GTP form localizes and binds through an amphiphilic helix to the membrane;

- The ALPS motif of the golgin GMAP-210 binds to only highly curved vesicles;

- The yeast transcriptional repressor Opi1 binds to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane in part through an amphiphilic helix;

- The heat shock protein Hsp12 has a long amphiphilic helix, which helps stabilize the membrane;

- The extremely long amphiphilic helix of perilipin 4 coats lipid droplets and stabilizes them, even in the absence of phospholipids.

Dietary uptake and release into the circulation

Now, how are the lipid nanoparticles assembled? We'll start with the dietary lipids: TAGs, glycerophospholipids, and cholesterol esters. The figure below shows key steps which are described in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)

Here are some key steps depicted in the figure:

- hydrolysis (lipolysis) of TAGs by pancreatic lipase, cholesterol esters (CE) by cholesterol esterase, and glycerophospholipids (GP) by phospholipase A2 in the lumen of the intestine. These enzymes interact at the interface of the lipid substrates and aqueous surroundings;

- the resulting products, which include free fatty acids (FA), 2-monoacylglycerol (MG), free cholesterol (FC), and lyso-glycerolphospholipids (lyso-GP), aggregate with the help of bile salts to form emulsions (like oil drops in water), which can be taken up by diffusion or possibly endocytosis when present in high amounts. Alternatively, membrane transporters (like FABPs and other proteins) can move them into the cell by facilitated diffusion;

- cytoplasmic transporters like fatty acid binding proteins move the lipolysis product to the ER where free fatty acids are reesterified. The enzymes involved include mono- and diacylglycerol acyltransferases (MGAT, DGAT) and sterol O-acyltransferase 2, also known as acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT-2). Multiple enzymes are involved in the resynthesis of glycerophospholipids);

- Apo B-48 is synthesized by ribosomes bound to the ER and interacts with a heterodimer of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein large subunit two (MTP) and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI). This facilitates the folding of apo B48 and loading of lipids using MTP into pre-chylomicrons;

- pre-chylomicron vesicles move to the Golgi with the help of Sar1b, a small G-protein (and GTPase) where the particle assembles to the full chylomicron, which is released from the cells as the mature large lipid nanoparticle.

An intriguing feature of lipases is that they work at the interface between the aqueous and nonaqueous (in this case, lipid nanoparticle) environments. Let's briefly consider the hydrolysis mechanism of TAGs by the equine pancreatic mechanism. This enzyme employs the same mechanism observed earlier for the hydrolysis of a peptide bond by serine proteases. A catalytic triad of Asp 176, His 263, and Ser 152 as a nucleophilic catalyst is shown in the partial reaction displayed in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

An acyl-Ser intermediate forms in step B (above) to form the product diacylglycerol after the collapse of an oxyanion intermediate in step A. In the second half of the reaction (not shown in its entirety), water cleaves the acyl-Ser intermediate through a hydrolysis reaction, reforming the active enzyme as it releases the free fatty acid, R3CO2H. Other lipases also employ the same catalytic triad.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows an expanded diagram showing the flow and fate of lipoproteins.

Chylomicrons interact with lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which also uses an Asp-His-Ser catalytic triad, to cleave fatty acid esters, allowing the delivery of free fatty acids to adipose cells. The adipocytes can also undergo de novo fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acids (FA) can also be produced by lipase-mediated lipolysis of stored TGs. These free fatty acids (FA) in the adipocyte have two fates. They can be reesterified to glycerol to form TAGs (TG in the figure) or be exported from the cell, where they bind to a plasma carrier protein and are transported to the liver for storage. There, the fatty acids can be taken up by various membrane protein importers, as indicated in the figure by the yellow boxes. As in adipose cells, fatty acids can be reesterified to form TAG stores, which can then be packaged into VLDL particles for export. The fatty acid delivered (or synthesized) could also be used for ATP production through the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation.

VLDL in circulation can undergo lipolysis by lipoprotein lipase to produce fatty acids for uptake in "extrahepatic" tissue (bottom right of the diagram). As fats are removed from VLDL, their density increases as it forms IDL and LDL, which could be considered VLDL "remnants". VLDL is very enriched in TAGs, but after metabolic processing, the resulting LDL is depleted in TAGs and enriched in cholesterol/cholesterol esters. LDL (not shown in the above figure) can be taken up (endocytosed) by the liver and other cells after binding to LDL receptors, which recognize apo-B100 and other apoproteins. This allows the delivery of predominantly cholesterol and cholesterol esters to tissues.

How do adipocytes and hepatocytes determine if free fatty acids should be esterified for storage or released for energy use by other tissues? We'll discuss that in a subsequent section. Still, the short answer is that in healthy fasting and exercise states, hormones (glucagon, epinephrine) activate lipolysis in the liver and adipose cells. In contrast, in the fed state, insulin promotes the storage of fatty acids as triacylglycerols.

Adipose cells don't assemble and release lipoproteins. Instead, they release free fatty acids into the circulation, which are carried by albumin, the major protein in serum or plasma. The iCn3D Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the complex of human serum albumin (HSA) binding seven 20:4Δ5,8,11,14 - arachidonic acids (1gnj ).

Given the multiple binding sites for fatty acids in albumin, it should come as no surprise that albumin also binds a host of small drugs, including medicinal drugs and toxins such as warfarin (blood thinner), diazepam, ibuprofen, indomethacin, and amantadine. These appear to bind preferentially at two primary drug binding sites. This binding is likely to be beneficial in delivering drugs through the circulation, but may not be effective if they aren't delivered to the target tissue.

We discussed the structure of micelles, spherical assemblies of single-chain amphiphiles that act as detergents. Oil from your clothes can enter the nonpolar interior of the detergent micelle and effectively solubilize the nonpolar molecule in the micelle, which is effectively a nanoparticle with a diameter of 5-15 nm. You should not be surprised to discover that lipoproteins can also carry fat-soluble vitamins, steroid-like endocrine-disrupting substances, and drugs.

Lipoprotein lipase

The enzyme that breaks now TAGs in circulating chylomicrons and VLDL is lipoprotein lipase (LPL). It is a soluble protein secreted by adipocytes and muscle cells, but is made by many cell types. It works at the luminal side of blood vessel endothelial cells. It is recruited to that membrane surface by binding to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) and the proteoglycan heparan sulfate at the cell surface.

What is so interesting is that GPIHBP1 is only synthesized by endothelial cells. When lipoprotein lipase is secreted from cells, it binds to the extracellular matrix heparan sulfate but dissociates on the cleavage of heparan sulfate by heparinases. GPIHBP1 is highly acidic with an intrinsically disordered N-terminal domain containing a sulfated tyrosine and is highly enriched in glutamates and aspartates, which are often sequential. Here is the single-letter sequence for amino acids 25-50 of the human version of GPIHBP1: EEEEEDEDHGPDDYDEEDEDEVEEEE. This sequence would have electrostatic and binding properties similar to the highly negatively charged heparan sulfate to which it also binds.

LPL also binds Ca2+, stabilizing the active dimeric form of the protein. Its enzymatic activity is activated by apoC-II. Like pancreatic lipase, it employs a Ser-132, Asp-156, and His-241 triad in its hydrolytic action on TAGs.

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)l below shows an interactive iCn3D model of LPL in complex with GPIHBP1, shown in brown (6E7K). The calcium ion is shown (grey spacefill) as well as the catalytic triad (labeled, sticks, CPK colors). The highly negatively charged stretch of amino acids in GPIHBP1 was not present in the crystal structure.

LDL: Receptor and Uptake

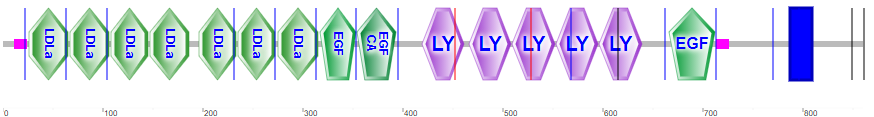

Lipoproteins are taken up into cells through receptor-mediated processes. Given its role in cardiovascular disease, let's focus on the LDL receptor. Remember that LDL is the primary carrier of cholesterol. The receptor is found in the cell membranes in most tissues. It has many domain repeats, as illustrated in the Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) calculated by SMART.

They include the N-terminal region cysteine-rich LDLa domains, which bind LDL, epidermal growth factor domains, LY (or LDLb) domains, and a transmembrane domain (blue rectangle).

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)s shows an interactive iCn3D model of the extracellular domain of the LDL receptor (1n7d).

Four tandem LY (LDLb) domains are in cyan, LDLa domains in magenta, and the EGF domain in dark orange. Glycans are represented in symbolic nomenclature. Zoom into the structure to see the two disulfide bonds in each LDLa domain and the Ca2+ ions that stabilize the domains.

LDL binds its receptor at a broad binding interface with multiple LDLa domains. This may explain why it can bind to lipid nanoparticles with apo B100 or apo E. The binding triggers a series of signaling events that lead to the internalization of the receptor by endocytosis through pits coated with the protein clathrin. These eventually fuse with lysosomes, where they are degraded and cholesterol is delivered to the cell. The steps are described in Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\).

The LDL receptor escapes lysosomal degradation and is continually delivered to the plasma membrane, along with newly synthesized receptors. A key protein, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9), a serine protease secreted by the liver, promotes the enzymatic degradation of the receptor and prevents its recycling to the membrane. It also binds to VLDLR and apolipoprotein E receptors, promoting their degradation. Its action reduces LDL clearance from the blood, increasing cardiovascular risk, so inhibitors of its action might be potent drugs to decrease circulating LDL.

The LDL receptor is just one member of the LDL receptor family. Other family members are illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\).

These include the LDL receptor (abbreviated Ldlr in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\), as well as the VLDL receptor (Vldlr), apolipoprotein E2 receptor (Apoe2), and LDL receptor-related proteins (Lrp)1-4. These also have an NPxY-motif (asterisk in the cytoplasmic domain) and a YWTD/β-propeller domain. Given the similarity in domain structure for the LDL family of receptors, the conformational flexibility of the apolipoproteins (at least free in solution), and similar structures for the exchangeable apolipoproteins, it shouldn't be surprising that the LDL receptor would interact with different classes of lipoproteins, albeit with different affinities.

As mentioned, apoE is found abundantly on HDL and VLDL/chylomicrons and their remnants. It is a ligand that binds to members of the LDL receptor family (remember that LDL generally binds the LDL receptor through apo B100).

Apolipoprotein E has three major variants (alleles) named ε2, ε3, and ε4 (also called ApoE2, 3, and 4). ApoE3 is the most prevalent. ApoE4 is found in only 15% of people, but in more than 50% with Alzheimer's Disease (AD), so it's a risk factor for this disease. AD affects the brain, which also contains up to 30% of the body's cholesterol, so aberrations in cholesterol transport and uptake in the brain are not unexpected in neurodegenerative diseases like AD.

ApoE is secreted by brain microglia (immune) cells and astrocytes (specialized glial cells). It assembles lipids into lipoproteins (HDL-like) and becomes the major vehicle for binding to and importing into neurons in a process initiated by the apoE receptor. The major apoE receptor for the clearance of lipoproteins in the brain is sortilin (SorLA in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)).

AD is characterized by the accumulation of a toxic amyloid prion protein called amyloid beta (Aβ). It is derived from selective but abnormal proteolysis of the neural integral membrane protein amyloid precursor protein (APP). Aβ aggregates to form insoluble neurotoxic extracellular Aβ amyloid plaques. Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) shows the process in normal and diseased cells.

The figure illustrates the normal (left) and aberrant processing of APP, as well as the family of proteases (secretases) involved. While the LDLR doesn't appear to bind to APP or influence its proteolytic processing, it does bind to Aβ. LRP1 is much bigger than LDLR, binds many ligands, and can be cleaved with the same enzymes as APP. It is expressed in the liver and especially in the brain and can regulate the removal of Aβ.

Immune cells in the brain, known as microglia, remove Aβ plaques (which are extracellular) through a process called phagocytosis. ApoE4 increases the inflammatory response (as measured by cytokine release) of the microglia (a good thing if the responses prevent infection or rid Aβ plaques) but also inhibits their ability to phagocytose the Aβ plaques and their metabolic activity.

An additional note: Having one ApoE4 allele appears to increase the risk of severe COVID-19 5-fold, while being homozygous for E4 leads to a 17-fold increased risk of severe disease.

Scavenger Receptors

Patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) have very high levels of LDL derived from defects in binding and uptake. Patients display fatty acid streaks under the vascular endothelial cells, morphing into calcified plaques and lesions filled with fat. Monocytes/macrophages, which migrate to sites of vascular injury, take up LDL and eventually differentiate into foam cells filled with lipids. Somehow, they have receptors that can bind and internalize LDL when the "normal" LDL receptor can't. Brown and Goldstein found that a specific chemical modification of LDL, acetylation, was necessary for the rapid uptake of "modified" LDL into macrophage receptors. These receptors are now called scavenger receptors (SRs).

There is a large family of scavenger receptors. It consists of classes A-J proteins that share functional but not sequence homology. They are found on macrophages and endothelium. They bind to and help remove "damage" signals, including damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and chemical species chemically modified by reactive oxygen species. The ligands are often polyanions, end-stage glycans, and extracellular matrix proteins. One such example is oxidized-LDL (produced in vivo or by chemical oxidative modification with malondialdehyde), which binds to the same scavenger receptor, SR-A1, also called Macrophage scavenger receptor type I, as acetylated-LDL. Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) shows the domain structure of the SR family.

SR-A1/MSR1 binds acetylated and oxidized LDL and β-amyloid (42), heat shock proteins (43), and PAMPs from some bacteria and viruses.

It's an enormous task to conceptualize all possible combinations of binding interactions among biological molecules. For visual learners and others, it's extremely useful to portray information on structures and interactions visually. An example using STRING, a database of known and predicted protein interactions, for the domain structure and protein:protein interactions of SR-A1/MSR1, is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\).

Note the interactions with apolipoproteins, apoB, apoE, and apoA1. The right-hand side of the figure also illustrates interactions with the collagen alpha-2(IV) chain (COL4A2), which is present in the extracellular matrix.

HDL metabolism: The Good Cholesterol

High LDL (and Lp(a)) levels pose a cardiovascular risk. In contrast, high levels of HDL and apo A-I are cardioprotective. HDL is involved in "reverse" cholesterol transport as it is taken up by the liver and sent to the intestines for elimination from the body. We have shown earlier in Figure 2 that HDL exists in many variants, reflecting the assembly and remodeling of HDL by enzymes and lipid transfer proteins. Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\) shows the lifecycle of HDL.

Secreted apo A-1 accretes lipids in the circulation through the transport and delivery of phospholipids and cholesterol from cell membranes by the ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC) A1 and G1. Another protein, the scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI), a polytopic integral membrane protein, is also involved. It acts as a receptor for various "lipid" ligands, including phospholipids, cholesterol esters, phosphatidylserine (an outer membrane marker for cell apoptosis), and lipoproteins such as HDL.

Other proteins are also involved in the assembly and remodeling of HDL. The lipolytic enzyme lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) removes a fatty acid from phospholipids and adds it to free cholesterol in the HDL to form cholesterol esters. Two major lipid transfer proteins, phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP), move lipids between HDLs and other lipoproteins. Cholesterol ester transport protein is made and secreted from the liver. It appears to exchange cholesterol esters from HDL for the return of TAGs from VLDL. Other enzymes (lipoprotein lipase and hepatic lipase) also form free fatty acids.

In the final step, HDL can deliver cholesterol ester and cholesterol to the liver by binding to the liver scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) mediated by apo A-I. The liver, adrenal gland, endothelial cells, macrophages, and many other tissues express the protein. The liver does not primarily take HDL up by endocytosis. In contrast, LDL is taken up by endocytosis mediated by the LDL receptor. SR-BI facilitates the transfer of cholesterol esters from bound HDL to the liver cell.

Unlike the widespread use of statins, which reduce LDL-C concentrations and clinically reduce cardiovascular disease risk, drugs such as fibrates, niacin, and inhibitors of cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP), which raise HDL levels, don't seem to lead to significant decreases in cardiovascular risk. The cholesterol delivered in excess to macrophages can form foam cells under the endothelial layer. Foam cells are proinflammatory and convert over time to cholesterol plaques. In contrast, HDL-C appears to have a direct atherogenic effect.

Summary

This chapter examines the critical roles of fats and lipoproteins in energy metabolism, focusing on the breakdown, transport, and storage of fatty acids and the complex regulation of lipid homeostasis.

Fatty Acid Metabolism and Storage:

The chapter begins by outlining the two primary sources of fatty acids—those derived from the diet (mainly as triacylglycerols, or TAGs) and those synthesized de novo from acetyl-CoA. TAGs are stored in specialized lipid droplets found predominantly in adipose tissue and, to a lesser extent, in muscle and liver cells. The discussion highlights the unique functions of white adipose tissue (WAT), which stores energy and plays an endocrine role by secreting adipokines such as leptin and adiponectin, and brown adipose tissue (BAT), which specializes in heat production through fatty acid oxidation facilitated by uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1).

Lipoprotein Structure and Function:

The transport of hydrophobic fatty acids in the aqueous bloodstream is achieved by lipoproteins—complex particles consisting of a lipid core (composed of TAGs, cholesterol esters, and free cholesterol) surrounded by a single phospholipid monolayer embedded with specific apolipoproteins. The chapter details how lipoproteins are classified by density (chylomicrons, VLDL, IDL, LDL, and HDL), and how their size, composition, and apolipoprotein content determine their metabolic fates. Key apolipoproteins such as apoB100, apoB48, apoA-I, and apoE are discussed in terms of their roles in stabilizing the particle, mediating receptor interactions, and influencing lipid exchange.

Lipoprotein Assembly, Uptake, and Remodeling:

The assembly of lipoproteins begins in the intestine (chylomicrons) and liver (VLDL), where dietary or endogenously synthesized lipids are packaged with apolipoproteins. The chapter explains how lipoproteins are processed in circulation through the action of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which hydrolyzes TAGs to release free fatty acids for uptake by peripheral tissues. The uptake of lipoproteins into cells occurs via receptor-mediated endocytosis, primarily through the LDL receptor for apoB100-containing particles. Scavenger receptors, which bind modified LDL, and the regulatory role of proteins such as PCSK9 in receptor recycling, further illustrate the complexity of lipid clearance and its impact on cardiovascular risk.

Albumin and Fatty Acid Transport:

The role of serum albumin as the major plasma protein for binding and transporting free fatty acids is also discussed. Albumin’s ability to bind various hydrophobic molecules—including drugs and toxins—demonstrates its critical role in maintaining lipid solubility and bioavailability in circulation.

Cardiovascular Implications:

Finally, the chapter connects lipid metabolism to human health by examining the impact of LDL and HDL on cardiovascular risk. High levels of LDL, especially modified forms such as Lp(a), are linked to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, while HDL is protective through its role in reverse cholesterol transport. The structure-function relationships of apolipoproteins, such as the amphiphilic helices in apoA-I and apoE, are emphasized as key determinants of lipoprotein behavior and interactions with cellular receptors.

In summary, this chapter integrates the biochemical pathways of fatty acid oxidation and lipoprotein metabolism, revealing how the body orchestrates the storage, transport, and utilization of lipids. It underscores the intricate regulation of these processes by hormonal signals, enzyme activities, and structural properties of macromolecular complexes, ultimately linking lipid metabolism to energy homeostasis and cardiovascular health.

.png?revision=1)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&height=270)