28.1: General Features of Signal Transduction

- Page ID

- 14990

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)-

Understand the Fundamental Importance of Cell Signaling:

- Explain how cell signaling enables cells to detect and respond to environmental changes and internal cues.

- Discuss why precise signal transduction is critical for processes such as cell growth, division, differentiation, and defense.

-

Describe the General Logic of Signal Transduction:

- Interpret the “black box” model of a cell, where specific inputs (signals) are processed to generate defined outputs (responses).

- Apply Boolean logic gate concepts (AND, OR, NOR, NAND, XOR) to understand how cells integrate multiple signals to produce appropriate responses.

-

Examine Mechanisms of Signal Initiation at the Membrane:

- Describe how extracellular signals bind to cell surface receptors and induce conformational changes that transduce the signal without the ligand entering the cell.

- Compare and contrast the two primary mechanisms for signal transduction: direct receptor conformational changes versus second messenger generation.

-

Explore the Role and Diversity of Second Messengers:

- Identify common second messengers (e.g., cAMP, cGMP, Ca²⁺, diacylglycerol, inositol trisphosphate) and describe their origins from receptor-mediated events.

- Explain how second messengers propagate signals within the cell and affect downstream processes.

-

Understand Protein Dynamics in Signal Transduction:

- Describe how signaling proteins transition between inactive and active states through conformational changes.

- Explain how post-translational modifications (such as phosphorylation) alter the activity, localization, and interaction of signaling proteins.

-

Detail the Roles of Protein Kinases and Phosphatases:

- Explain the general reaction mechanisms of protein kinases (using ATP to phosphorylate target substrates) and phosphatases (removing phosphate groups).

- Classify kinases into major families (e.g., AGC, CAMK, CKI, CMGC, STE, PTK, PTKL, RGC) and discuss how this diversity contributes to signaling specificity.

- Discuss how the large number of kinases and phosphatases in the human genome allows for fine-tuned regulation and redundancy in signal transduction.

-

Relate Signal Transduction to Cellular Organization and Localization:

- Explain how protein targeting sequences and post-translational modifications direct the spatial and temporal localization of signaling proteins.

- Describe how the movement of signaling molecules (both proteins and second messengers) enables signal propagation from the plasma membrane to intracellular organelles, including the nucleus.

-

Integrate Approaches to Studying Signal Transduction Pathways:

- Compare the strategy of tracing signaling events from the membrane inward with the analysis of recurring signaling motifs across pathways.

- Appreciate the use of mathematical modeling and systems biology approaches in understanding complex, interconnected signaling networks.

These learning goals are designed to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the principles and mechanisms of cell signaling, from the initial receptor-ligand interaction to the intricate network of intracellular events that regulate cellular responses.

Introduction to Cell Signaling

Cell signaling is at the heart of biology. A cell must know how to respond to chemical signals in its environment. These signals control every aspect of cell life and interactions. A cell must sense when to grow, divide, and die. It must sense the presence of foreign and toxic molecules. It must defend itself. The membrane represents the divide between the outside and the inside world. Signals must cross that divide, and this most often happens without the signaling molecule entering the cell. Just the signal itself is transduced across the membrane. And it doesn't stop there. Internal signaling, also across internal membranes of organelles in eukaryotes, propagates spatially and temporally across the cytoplasm in all cells (prokaryotes, Archaea, and eukaryotes). It's impossible to describe the myriad of processes that occur in cell signaling in a single chapter, but we will do our best to present the common features used across cells.

In addition, signals in complex organisms must be integrated within tissues and organs, between organs (such as the brain and liver), and throughout the entire organism. Mathematical modeling is critical in understanding the complexity of these interconnected interactions. Consider the flee, fight, or freeze responses. What if you were walking down the street and suddenly saw a tiger approaching you? Most would flee. In that process, the neural, muscular, and metabolic systems must be integrated. The resting state is followed by the activation of the fight/flee response, the maintenance of the fleeing state, and then the return to the resting state. An alternative is the freeze response, which in some situations would be adaptive.

Perhaps the most complex signaling occurs in the great communication networks in the neural and immune systems. Think of it. You can experience a traumatic or emotionally-charged event once and remember it forever. Ordinary events leave less permanent traces. The biochemical changes that accompany long- and short-term memory are fascinating.

Let's consider general principles for signal transduction across the membranes of any cell that must respond to its environment. Typically, the agent that signals a cell to respond is a molecular signal. Signaling can also be mediated by pressure (for touch and hearing) or light for vision. The chemical signal binds either to a cell surface receptor or to a cytoplasmic receptor if the signaling agent is hydrophobic and can transit the membrane bilayer.

The logic of signaling

To a first approximation, you could consider a cell as a black box, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), with input (an external molecule for example) and resulting output signals within a cell, such as activation of gene transcription, trafficking of molecules within the cell, chemical reactions, or even export of molecules from the cell. There could be one or more signals, and one or more outputs. The inputs might arrive gradually and reach a threshold before triggering an output, or the input might be abrupt, leading to an immediate output. This Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\):

Note the use of terminology taken from the world of electronics. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the similarity in the complexity of an electronic wiring diagram (left) to the interconnected metabolic pathways of a cell (right).

The analogy is much greater than you might think. Cell signaling researchers have adopted the language and symbols of electronics as they consider how two inputs could lead to different output signals. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) illustrates a truth table featuring various Boolean operator logic gates and symbols commonly used by electrical engineers, which also apply to signals transmitted to cells and their corresponding outputs. Two input signals, A and B, arrive at different logic gates named AND, NOR, OR, XOR, AND, and NAND. 0 indicates no signal (either input or output) while 1 indicates a signal (either input or output).

Each of these logic gates leads to different outputs:

- AND gates require both A and B input signals for an output;

- OR gates require either A or B or both for an output signal;

- NOR gates require neither A or B for an output signal;

- NAND gates normally have an output signal unless both inputs A and B are present;

- XOR (Exclusionary OR) gates give a signal if the two inputs A and B differ.

An example of an analogous biological AND gate is the N-WASP protein, a homolog of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP). This protein regulates actin polymerization and binds multiple signals. Stimulation with two proteins, Cdc42 and phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2), activates polymerization.

Researchers are designing protein logic gates by creating a series of heterodimeric proteins. Consider the following heterodimers: A:A', B:B', and C:C', where the second member in each pair is different from the first and bound reversibly through noncovalent interactions (indicated by the colon :) Other versions could exist, such as A:C'. An AND gate for the formation of an A:C' dimer would be made by making the covalent, single molecules A'-B and B'-C. The A:C' dimer could form only in the presence of both A'-B and B'-C. This is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Signals and their responses must occur at the right time under the right conditions and for the right duration. Under opposing sets of conditions (for example, well-fed and starving), opposing signaling pathways, mediated by different signaling molecules, must be mutually integrated and regulated so that one is activated and the other is inhibited. Methods must be in place to terminate signal effects.

Given the complexity of signaling pathways, it is challenging to present the material effectively in a single chapter. Binding initiates and mediates almost all biological events. That binding must also be specific to avoid off-target effects. If you were to predict what biomolecule could confer specificity in the binding of a signal and allow changes from the unbound to bound state, you would certainly pick proteins. Protein:ligand binding is key to understanding biosignaling. Other types of biomolecules, such as lipids and nucleic acids, are also involved and play crucial roles. Still, they typically play a role downstream from the initial protein:signal binding event. Hence, we will focus primarily on signaling proteins and conformational and activity changes that occur upon signal binding.

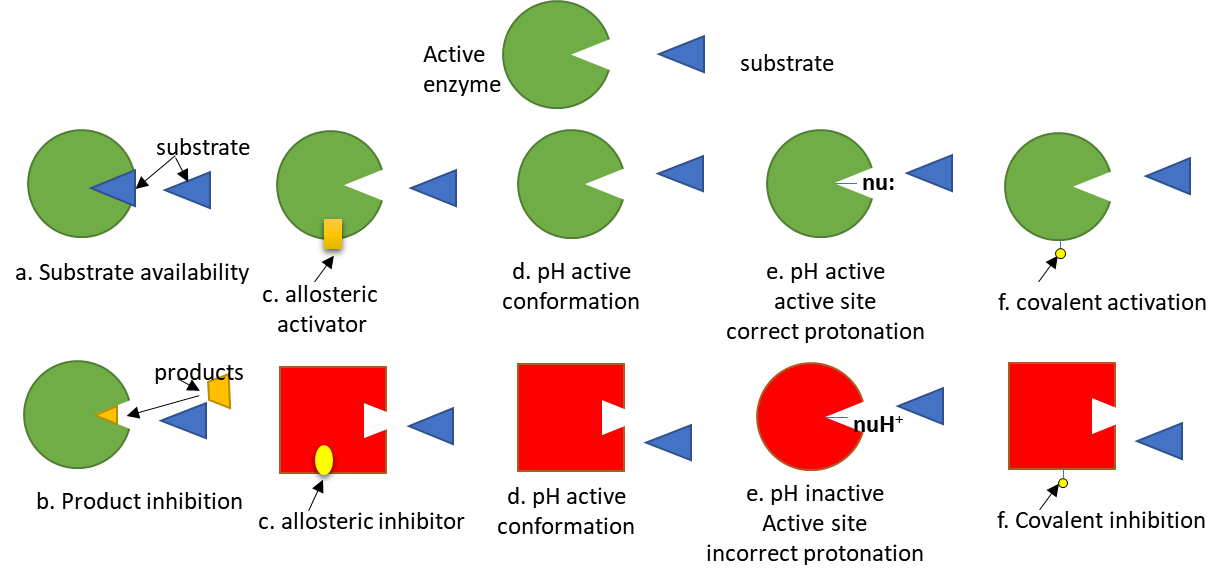

To simplify protein involvement in signaling, we can assume that signaling proteins exist in both active and inactive states. The states are interconvertible, meaning they are reversible. Let's assume the signaling protein is an enzyme. The activity of the enzyme depends on many factors, as described in Figure (\PageIndex{5}\) below. The green color represents the active enzyme, while red indicates the inactive enzyme.

Of course, proteins that are not enzymes (for example, transcription factors) can be regulated similarly.

In addition, the amount (and localization as well) of a signaling protein can regulate the activity of the protein, as illustrated in Figure (\PageIndex{6}\) below.

Each signaling protein can be considered to be a node in a larger pathway consisting of interconnected nodes. This chapter on cell signaling can hence be viewed as a capstone to Unit 1, which explores the structure and function of biomolecules, and as a prelude to the study of whole metabolic pathways.

Second Messengers and Signal Translocation

The chemical species that trigger signaling typically bind to a target protein transmembrane receptor on the cell surface, but do not themselves enter the cell. Just the signal enters the cell. If you were to hypothesize how that might happen, you would predict two mechanisms:

- An integral transmembrane receptor undergoes a conformational change upon binding that propagates to its cytoplasmic domain, allowing it to interact with other cytoplasmic proteins or the cytoplasmic domains of other membrane proteins, thereby transmitting the signal into the cytoplasm.

- The bound conformation of the receptor has enzyme activity and can catalyze chemical reactions on the luminal side of the membrane. This could include the chemical modification of proteins or the synthesis of new small molecules from cell metabolites. These new small molecules are called second messengers. They could be formed in the membrane bilayer or the cytoplasm.

There are several diverse types of second messengers. Two common examples are cyclic derivatives of small nucleotides, including cyclic AMP (cAMP), derived from ATP, and cyclic GMP (cGMP), derived from GTP. Ca2+ ions are typically found in low concentrations in the cytoplasm, as they are actively pumped into internal organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Signaling processes can release Ca2+ ions in waves within the cell. Membrane lipids are also processed to form second messengers. Membrane phospholipids can be cleaved by cell-signaling-activated lipases to form free arachidonic acid, sphingosine, diacylglycerol, and inositol-trisphosphate, which can act as second messengers. Redox signaling in the cell can also occur through hydroperoxides acting as second messengers.

What if the cell's response requires gene transcription? Somehow, the signal has to translocate from the cell membrane through the cytoplasm through the nuclear membrane into the nucleus. Hence, a series of translocations of multiple downstream signaling events must occur.

We have already seen how newly synthesized proteins have signal sequences that target them to specific cellular locations, such as the cell membrane, mitochondria, nucleus (via nuclear localization sequences - NLS), or for export via RAN. Proteins involved in signaling can also move throughout the cell as part of the signaling process. Likewise, we have seen how cytoplasmic proteins can be targeted to membranes by attachment of fatty acids or isoprenoids.

Post-translational modification of signaling proteins

Nature has chosen the post-translational modifications (PTM) of proteins as a ubiquitous way to alter the signaling states of proteins. As we have seen previously, PTMs can alter protein conformation. They can also present new binding interfaces that allow interaction with other signaling proteins. The main (but not the only) PTM used for signaling is the reversible phosphorylation of the OH-containing amino acid side chains (Tyr, Ser, and Thr) as well as histidine (mostly in prokaryotes); therefore, we will focus on these. Enzymes that catalyse the phosphorylation of proteins are called protein kinases. Reversibility is important since if phosphorylation of a target protein is associated with a specific signaling change (either activation or inhibition), then dephosphorylation can easily reverse the signaling event. Enzymes that dephosphorylate phosphoproteins are called protein phosphatases. Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows the generic reaction of protein kinases and phosphatases.

There appear to be 518 protein kinases and 199 protein phosphatases encoded in the human genome. Why so many? If only one protein kinase existed, a single mutation in it would be disastrous. In addition, the large number of kinases and phosphatases allows for great control in the specificity of these enzymes for their target protein substrates.

Kinases

Kinases are a class of enzymes that use ATP to phosphorylate molecules within the cell.

The names given to kinases show the substrate that is phosphorylated by the enzyme. For example:

- hexokinase - an enzyme that uses ATP to phosphorylate hexoses.

- protein kinase - enzymes that use ATP to phosphorylate proteins within the cell. (Note: Hexokinase is a protein, but is not a protein kinase).

- phosphorylase kinase: an enzyme that uses ATP to phosphorylate the protein phosphorylase within the cell

If a kinase phosphorylates a protein, the phosphate group must eventually be removed by a phosphatase through a process of hydrolysis. If it weren't, the phosphorylated protein would be in a constant state of either being activated or inhibited. Kinases and phosphatases regulate all aspects of cellular function. About 1-2% of the entire genome encodes kinases and phosphatases.

Kinases can be classified in many ways. One is substrate specificity: Eukaryotes have different kinases that phosphorylate serine/threonine or tyrosine side chains. Prokaryotes also have His and Asp kinases, but these are unrelated structurally to the eukaryotic kinases. There are 11 structurally different families of eukaryotic kinases, which all fold to a similar active site with an activation loop and catalytic loop between which substrates (ATP and the OH-containing side chain) bind. Simple, single-cell eukaryotic cells (like yeast) have predominantly cytoplasmic Ser/Thr kinases, while more complex eukaryotic cells (like human cells) have many Tyr kinases. These include the membrane-receptor Tyr kinases and the cytoplasmic Src kinases.

Manning et al. have analyzed the entire human genome (DNA and transcripts) and have identified 518 different protein kinases, which cluster into seven main families as shown in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) below. Sequence comparisons of catalytic domains determined family membership. The entire repertoire of kinases in the genome is referred to as the kinome. Alterations in 218 of these appear to be associated with human diseases.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| AGC | Contains PKA, PKG, and PKC families |

| CAMK | Ca2+/CAM-dependent PK |

| CKI | Casein kinase 1 |

| CMGC | Contain CDK, MAPK, GSK3, CLK families |

| STE | homologs of yeast sterile 7, 11, 20 kinases; MAP Kinase |

| PTK | Protein tyrosine kinase |

| PTKL | Protein tyrosine kinase-like |

| RGC | Receptor guanylate kinase |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): The human kinome

Phosphatases

There are three main families of phosphatases, the phospho-Tyr phosphatases (PTP), the phospho-Ser/Thr phosphatases, and those that cleave both. Of all phosphorylation sites, most (86%) are on Ser, 12% involve Thr, and about 2% are on Tyr. They can also be categorized by their molecular sizes, inhibitors, divalent cation requirements, and other characteristics. In contrast to kinases, which differ in the structure of their catalytic domains, many phosphatases (PPs below) gain specificity by binding protein cofactors that facilitate translocation and binding to specific phosphoproteins. The active phosphatase, hence, often consists of a complex of the phosphatase catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit. Regulatory subunits for Tyr phosphatases may contain a SH2 domain, allowing binding of the binary complex to autophosphorylated membrane receptor Tyr kinases.

Given this background, we can now systematically explore signal transduction methods. There are two major ways to organize our discussions:

- start from the binding of the molecular signal at the cell membrane and trace the signaling events inward into the cell, potentially to the nucleus and gene expression

- describe recurring motifs found in most pathways.

We will use a combination of both, but it makes sense to start with the signaling proteins at the cell membrane. Next, we will focus on second messengers. We will follow that with detailed explorations of kinases and phosphatases, as well as specific signaling pathways.

Summary

This chapter introduces the fundamental principles and common mechanisms of cell signaling, emphasizing how cells sense and integrate external cues to coordinate appropriate responses. Although cell signaling involves a vast array of specialized pathways, the chapter distills the core concepts that underlie these processes, providing a framework for understanding how signals are transmitted from the cell membrane to intracellular targets and even across tissues.

Key Themes

-

The Central Role of Cell Signaling:

Cells must constantly interpret environmental signals to decide when to grow, divide, or initiate defensive responses. The plasma membrane acts as a critical barrier, where signals are often transduced without the signal molecule entering the cell. This ensures that cells can rapidly respond to changes in their surroundings. -

Signal Integration and the Logic of Communication:

The chapter presents the cell as a "black box" where specific inputs (e.g., ligands, light, pressure) are converted into well-defined outputs such as gene transcription, protein trafficking, or metabolic changes. Analogies to electronic circuits—including Boolean logic gates (AND, OR, NOR, NAND, XOR)—illustrate how multiple signals can be integrated, leading to precise cellular outcomes. -

Mechanisms of Signal Initiation and Propagation:

Two primary modes of transducing signals across membranes are described:- Conformational Change in Receptors:

Ligand binding induces structural alterations in transmembrane receptors that are transmitted to the cytoplasmic domains, which then interact with downstream signaling proteins. - Generation of Second Messengers:

Some receptors possess enzymatic activities that generate small, diffusible molecules (such as cAMP, cGMP, Ca²⁺, diacylglycerol, and inositol trisphosphate) which serve as intracellular second messengers. These messengers amplify the signal and propagate it throughout the cell.

- Conformational Change in Receptors:

-

Post-Translational Regulation of Signaling Proteins:

Signaling proteins typically exist in reversible inactive and active states. Their activity is regulated by post-translational modifications—most notably phosphorylation by protein kinases and dephosphorylation by phosphatases. The large number of kinases and phosphatases in the human genome allows for highly specific and dynamic control of signaling pathways. -

Spatial and Temporal Coordination of Signals:

Beyond the initial activation at the cell membrane, signaling events often involve the translocation of molecules, the integration of signals at the nuclear level, and even the modeling of signal networks using mathematical frameworks. This multi-layered coordination ensures that complex physiological processes, such as the "fight or flight" response, are executed with precision. -

Integration in Complex Systems:

In multicellular organisms, cell signaling not only orchestrates intracellular responses but also facilitates communication among cells, tissues, and organs. This integration is vital for the coordinated regulation of functions such as metabolism, immunity, and neural activity, and it underlies phenomena like memory and behavior.

Conclusion

Overall, this chapter provides a broad yet detailed introduction to cell signaling, outlining the critical steps from receptor activation and second messenger generation to the downstream regulation of cellular functions. By drawing parallels between electronic circuits and cellular networks, the chapter emphasizes how cells process complex information to generate appropriate responses. This foundational knowledge is essential for understanding both normal cellular function and the dysregulation of signaling pathways in diseases such as cancer and neurodegeneration.