8.6: Enzymes for Genetic modifications

- Page ID

- 95200

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)It is difficult to read newspapers and newsmagazines without encountering the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system that has the potential to make gene editing routine in disease diagnosis, treatment, and cure, as well as in genetic modification of organisms to improve their quality and quantity for food and natural product production. In this chapter section, we will explore the mechanism of restriction enzymes that made gene cloning possible as well as the CRISPR-Cas gene editing system.

Restriction Endonucleases

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, or restrictase is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class of the broader endonuclease group of enzymes. Restriction enzymes are commonly classified into five types, which differ in their structure and whether they cut their DNA substrate at their recognition site, or if the recognition and cleavage sites are separate from one another. To cut DNA, all restriction enzymes make two incisions, once through each sugar-phosphate backbone (i.e. each strand) of the DNA double helix. Here we will focus on the Type II restriction enzymes that are routinely used in molecular biology and biotechnology applications.

As with other classes of restriction enzymes, Type II Restriction Enzymes occur exclusively in unicellular microbial life forms––mainly bacteria and archaea (prokaryotes)––and are thought to function primarily to protect these cells from viruses and other infectious DNA molecules. Inside a prokaryote, the restriction enzymes selectively cut up foreign DNA in a process called restriction digestion; meanwhile, host DNA is protected by a modification enzyme (a methyltransferase) that modifies the prokaryotic DNA and blocks cleavage. Together, these two processes form the restriction-modification system.

The first Type II Restriction Enzyme discovered was HindII from the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae Rd. The event was described by Hamilton Smith (Figure 7.23) in his Nobel lecture, delivered on 8 December 1978:

‘"In one such experiment we happened to use labeled DNA from phage P22, a bacterial virus I had worked with for several years before coming to Hopkins. To our surprise, we could not recover the foreign DNA from the cells. With Meselson’s recent report in our minds, we immediately suspected that it might be undergoing restriction, and our experience with viscometry told us that this would be a good assay for such an activity. The following day, two viscometers were set up, one containing P22 DNA and the other Haemophilus DNA. Cell extract was added to each and we began quickly taking measurements. As the experiment progressed, we became increasingly excited as the viscosity of the Haemophilus DNA held steady while the P22 DNA viscosity fell. We were confident that we had discovered a new and highly active restriction enzyme. Furthermore, it appeared to require only Mg2+ as a cofactor, suggesting that it would prove to be a simpler enzyme than that from E. coli K or B.

After several false starts and many tedious hours with our laborious, but sensitive viscometer assay, Wilcox and I succeeded in obtaining a purified preparation of the restriction enzyme. We next used sucrose gradient centrifugation to show that the purified enzyme selectively degraded duplex, but not single-stranded, P22 DNA to fragments averaging around 100 bp in length, while Haemophilus DNA present in the same reaction mixture was untouched. No free nucleotides were released during the reaction, nor could we detect any nicks in the DNA products. Thus, the enzyme was clearly an endonuclease that produced double-strand breaks and was specific for foreign DNA. Since the final (limit) digestion products of foreign DNA remained large, it seemed to us that cleavage must be site-specific. This proved to be case and we were able to demonstrate it directly by sequencing the termini of the cleavage fragments.’"

Restriction enzymes are named according to the taxonomy of the organism in which they were discovered. The first letter of the enzyme refers to the genus of the organism and the second and third to the species. This is followed by letters and/or numbers identifying the isolate. Roman numerals are used to specify different enzymes from the same organism. For example, the enzyme ‘HindIII’ was discovered in Haemophilus influenzae, serotype d, and is distinct from the HindI and HindII endonucleases also present within this bacterium. The DNA-methyltransferases (MTases) that accompany restriction enzymes are named in the same way, and given the prefix ‘M.’. When there is more than one MTase, they are prefixed ‘M1.’, ‘M2.’, etc, if they are separate proteins or ‘M1∼M2.’ when they are joined.

Restriction Enzymes that recognize the same DNA sequence, regardless of where they cut, are termed ‘isoschizomers’ (iso = equal; skhizo = split). Isoschizomers that cut the same sequence at different positions are further termed ‘neoschizomers’ (neo = new). Isoschizomers that cut at the same position are frequently, but not always, evolutionarily drifted versions of the same enzyme (e.g. BamHI and OkrAI). Neoschizomers, on the other hand, are often evolutionarily unrelated enzymes (e.g.EcoRII and MvaI).

Type II Restriction Enzymes are a conglomeration of many different proteins that, by definition, have the common ability to cleave duplex DNA at a fixed position within, or close to, their recognition sequence. This cleavage generates reproducible DNA fragments, and predictable gel electrophoresis patterns, properties that have made these enzymes invaluable reagents for laboratory DNA manipulation and investigation. Almost all Type II Restriction Enzymes require divalent cations, usually Mg2+, as essential components of their catalytic sites. Ca2+, on the other hand, often acts as an inhibitor of Type II Restriction Enzymes.

The recognition sequences of Type II Restriction Enzymes are palindromic, with two possible types of palindromic sequences. The mirror-like palindrome is similar to those found in ordinary text, in which a sequence reads the same forward and backward on a single strand of DNA, as in GTAATG. The inverted repeat palindrome is also a sequence that reads the same forward and backward, but the forward and backward sequences are found in complementary DNA strands (i.e., of double-stranded DNA), as in GTATAC (GTATAC being complementary to CATATG). Inverted repeat palindromes are more common and have greater biological importance than mirror-like palindromes. The position of cleavage within the palindromic sequence can vary depending on the enzyme and can produce either single-stranded overhanging sequences (sticky ends) or blunt-ended DNA products. Examples of staggers and blunt end cuts by restriction enzymes are shown in Table \(\PageIndex{8}\) below.

| EcoR1 | |

| Sma1 |

Table \(\PageIndex{8}\): Staggered and blunt end cut sequences by EcoR1 and Sma1

Methylation can be used by the host to protect its own genome from cleavage. For example, the methylation of the EcoRI recognition sequence by the M.EcoRI methyltransferase (MTase), changes the sequence from GAATTC to GAm6ATTC (m6A = N6-methyladenine). This modification completely protects the sequence from cleavage by EcoRI.

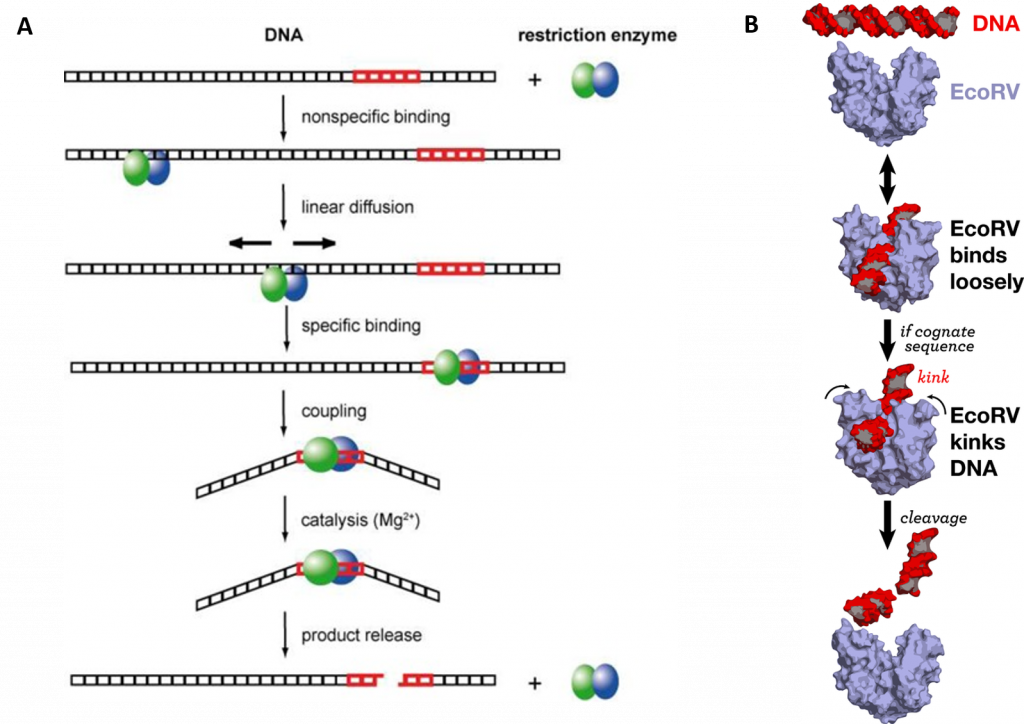

Type II Restriction Enzymes initially bind non-specifically with the DNA and proceed to slide down the DNA scanning for recognition sequences as shown in Figure (\PageIndex{36}\):. Upon binding to the correct palindromic sequence the enzyme associates with the metal cofactor and mediates catalytic cleavage of the DNA using the mechanism of strain distortion and catalysis by approximation.

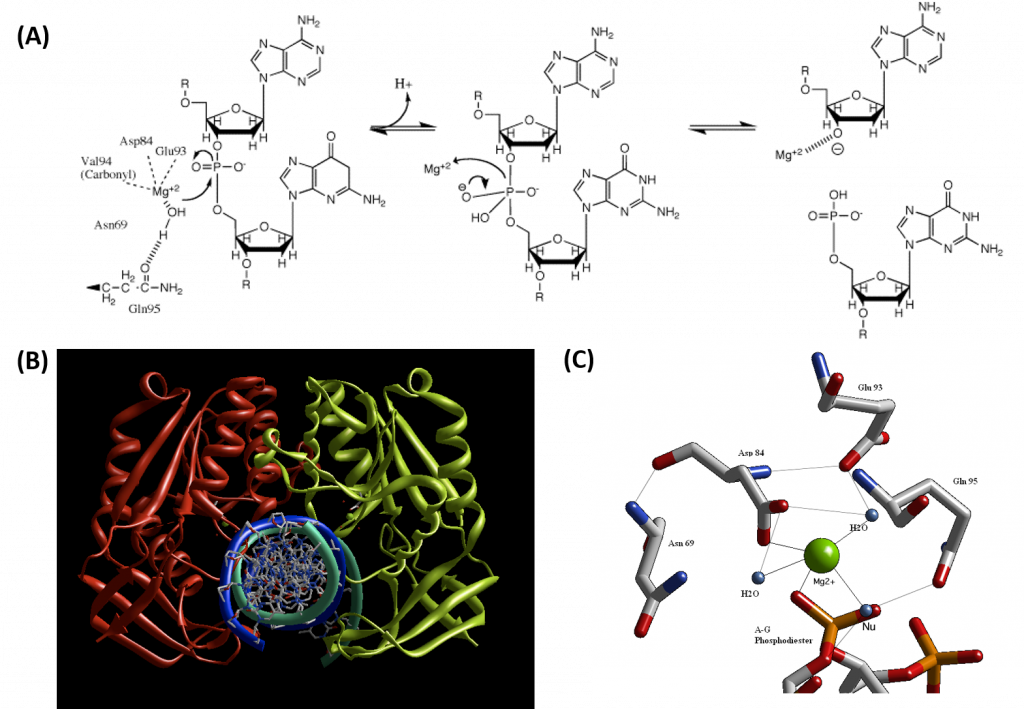

One of the most important questions regarding the catalytic mechanism of a hydrolase is whether hydrolysis involves a covalent intermediate, as is typical for the proteases described previously. This can be decided by analyzing the stereochemical course of the reaction. This was done first for EcoRI, and later for EcoRV. Both enzymes were found to cleave the phosphodiester bond with inversion of the chiral center at the phosphorus, which argues against the formation of a covalent enzyme–DNA intermediate. Thus, it is proposed that cleavage involves the direct nucleophilic attack of the substrate by a water molecule, as shown in Figure (\PageIndex{37}\) below.

Type II restriction enzymes typically form a homodimer when binding with DNA, as shown in the crystal structure of BglII in Figure 7.26B. BglII catalyzes phosphodiester bond cleavage at the DNA backbone through a phosphoryl transfer to water. Studies on the mechanism of restriction enzymes have revealed several general features that seem to be true in almost all cases, although the actual mechanism for each enzyme is most likely some variation of this general mechanism (Figure 7.25). This mechanism requires a base to generate the hydroxide ion from water, which will act as the nucleophile and attack the phosphorus in the phosphodiester bond. Also required is a Lewis acid to stabilize the extra negative charge of the pentacoordinate transition state phosphorus, as well as a general acid or metal ion that stabilizes the leaving group (3’-O−). In some Type II Restriction Enzymes, two divalent metal cofactors are required (such as in EcoRV and BamHI), whereas other enzymes only require one divalent metal cofactor (such as in EcoRI and BglII).

Structural studies of endonucleases have revealed a similar architecture for the active site with the residues following the weak consensus sequence Glu/Asp-(X)9-20-Glu/Asp/Ser-X-Lys/Glu. BglII's active site is similar to other endonucleases', following the sequence Asp-(X)9-Glu-X-Gln. In its active site, there sits a divalent metal cation, most likely Mg2+, that interacts with Asp-84, Val-94, a phosphoryl oxygen, and three water molecules. One of these water molecules is able to act as a nucleophile because of its proximity to the scissile phosphoryl group (Figure 7.26A). The nucleophilic water molecule is positioned for attack onto the phosphoryl group by a hydrogen bond with the side chain amide oxygen of Gln-95 and its contact with the metal cation. Interaction with the metal cation effectively lowers its pKa, promoting the water's nucleophilicity as shown in Panel A of Figure (\PageIndex{38}\) below (from Pingoud, A., Wilson, G.G., and Wende, W. (2014) Nuc Acids Res 42(12):7489-7527). During hydrolysis, the divalent cation can stabilize the 3'-O- leaving group and coordinate proton abstraction from one of the coordinated water molecules

CRISPR-Cas 9

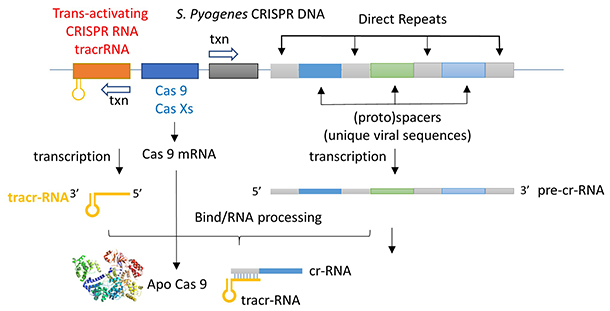

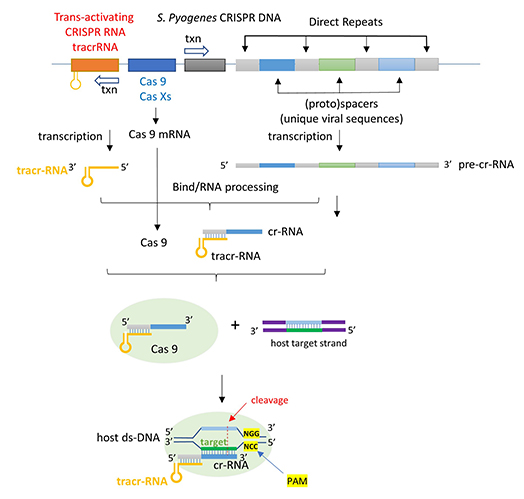

The CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) operon was initially discovered as part of the adaptive immune system of bacteria and archaea, which must defend themselves against viruses (bacteriophages) and unwanted plasmids transferred from both bacteria. It would be ideal for bacteria to recognize previous exposure to viruses and their nucleic acids as the basis of their immunological memory system. Given the tendency of viral DNA to integrate into the host genome (which allows later transcription and translations of the viral genes in the process of new virus production), immunological memory could be based on that viral integrated DNA. Without going into detail, viral DNA can be integrated between two direct repeats in the bacterial genome. DNA from different viruses from previous exposures is also incorporated in the same fashion. One site of integration is the CRISPR operon. The DNA of the CRISPR operon contains both protein-coding and noncoding regions which are transcribed and processed to form at least three RNA molecules, as shown in Figure (\PageIndex{24}\) below.

- a coding Cas 9 mRNA this is translated to produce the Cas 9 (CRISPR-associated protein);

- a noncoding cr-RNA (CRISPR RNA)

- a noncoding tracr-RNA (trans-activating CRISPR RNA)

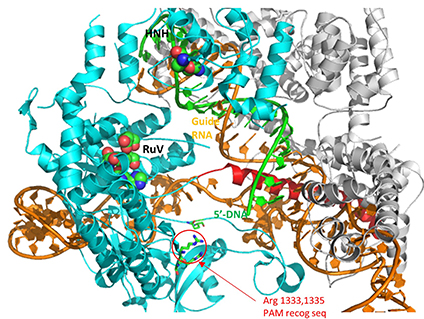

The two mature noncoding RNAs eventually associate to form a binary complex. When using CRISPR-Cas 9 in eukaryotic gene editing applications, the two noncoding RNAs are covalently combined into one large synthetic guide RNA (sg-RNA), described later in this section. The Cas 9 protein is an endonuclease that cleaves both strands of bound target dsDNA in a blunt-end fashion at specific sequences. This occurs after the DNA binds to two arginines (1333 and 1335) in Cas9 through a short (3-5+ bases) recognition protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) located three base pairs from the cleavage site. The DNA must also bind in a complementary and specific fashion to the protein-bound noncoding cr+tracr-RNAs (or a single sg-RNA molecule for gene editing applications). Binding and cleavage of target DNA would render DNA from an invading bacteriophage inactive.

Basic research into the bacterial CRISPR system has led to revolutionary and explosive applications of this gene editing system in eukaryotes. The hope is that CRISPR technology will give us a precise and incredibly cheap way to do gene therapy in diseased cells and organisms. Given its role in transforming our ability to edit the genome and potentially cure genetically-based diseases, we will offer a detailed explanation of its mechanism.

We have discussed the structure and function of many proteins. Protein enzymes are key to life as they catalyze almost all biological reactions. Most key enzymes are regulated. The activity of Cas 9 must be carefully controlled. Think of the consequences if the enzyme were to cleave promiscuously at off-site targets! This section will help you understand several critical features of this enzyme:

- How does the enzyme find its correct target site, a 20 nucleotide DNA sequence, and a proximal PAM site, among all the possible alternative sites? Think of how many PAM sequences there must be in the host DNA genome!

- How can the enzyme be "turned" on when it finds its target site and remain off when free, but more importantly when it is bound off-site?

First, we will discuss the apo- form of the enzyme without bound substrate and RNA.

Apo- and Holo-Cas 9

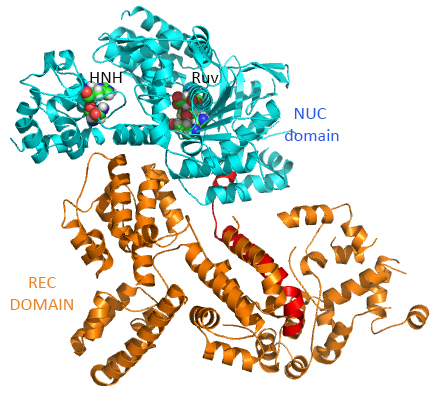

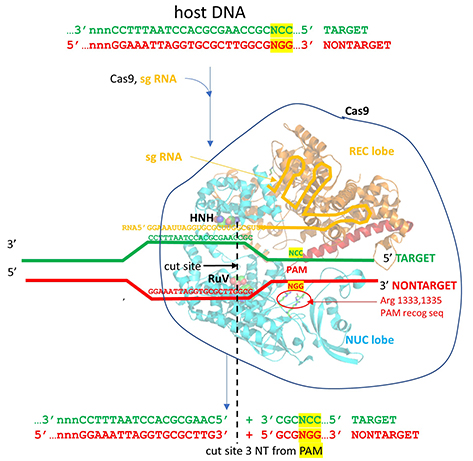

This section will focus on the Type II-A Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpyCas9 or SpCas9). Cas 9 is an endonuclease that cleaves both strands of DNA 3 base pairs from a DNA motif, NCC/NGG, called PAM. It has two distinct lobes. The nuclease lobe (NUC), amino acids 1-56 and 718-1368, has two different nuclease domains for the two cleavages. The recognition or receptor lobe (REC), amino acids 94-717, interacts with the RNA molecules. There is also an arginine-rich bridge helix (57-93).

The enzyme has two catalytic nuclease domains:

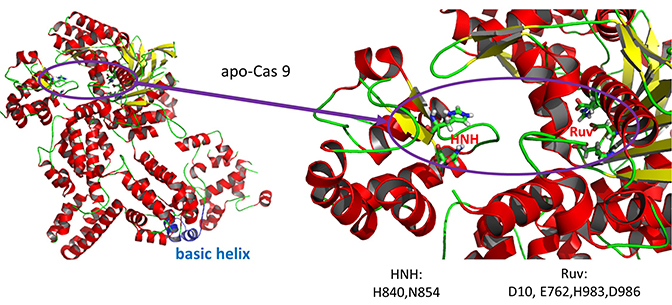

- HNH-like nuclease domain cleaves the "target" DNA strand, which is complementary to the RNA the confers specificity to the enzyme. The key catalytic residues are His 840 and Asn 854. It also contains a Mg ion;

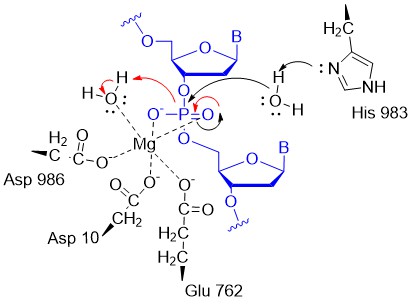

- Ruv-like domain that cleaves the complementary "non-target" strand with key active site residues Asp 10, Glu 762, Asp 986, and His 983. It also contains a bound Mn ion. The two lobes are separated by two linkers, amino acids 712-717, and an arginine-rich bridge (basic helix - BH), amino acids 628-658.

The overall structure of the apoenyzme (without bound RNA and DNA,pdb id 4cmp) is shown in Figure (\PageIndex{25}\) below, which shows the NUC domain (light blue) with the two catalytic domains (HNH and Ruv), the REC domain (orange) and the BH helix (red).

A close up view showing the two catalytic sites is shown in Figure (\PageIndex{26}\) below.

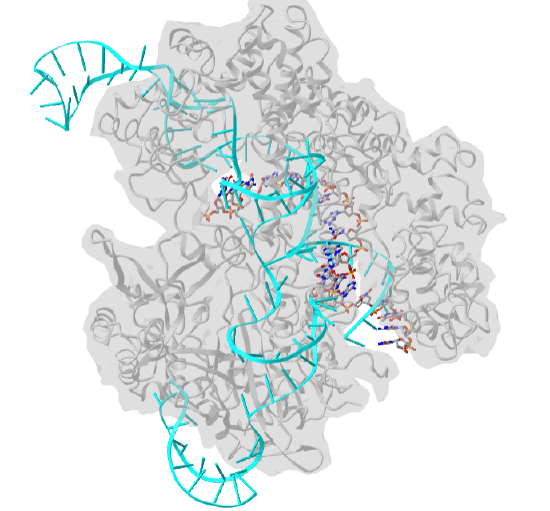

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA (4OO8) (long load time). The Cas9 enzyme is shown as a gray transparent surface with an underlying cartoon rendering. The DNA is shown as colored sticks. The RNA is shown as a cyan cartoon.

Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\): Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA (4OO8). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...RjzJBFVt5qRjS7 (long load time)

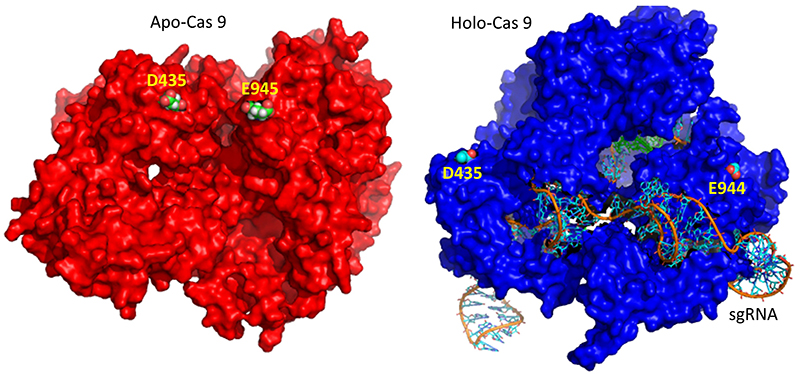

A comparison of the crystal structure of the apo-Cas 9 and the ternary Cas 9: sgRNA:DNA target strand complex shows a significant conformational change on binding nucleic acids. The structure of the holoenzyme (ternary complex) is shown in Figure (\PageIndex{28}\) below.

The extent of the conformation change between apo- and holo-Cas 9 enzymes can be seen by examining the distance between D435 and E 944/945 in Figure (\PageIndex{29}\) below. The importance of this change will be described later.

Figure (\PageIndex{30}\) below shows the pathway from the transcription of the relevant CRISPR genes (coding and noncoding) to the assembly of the ternary complex and the blunt end cut of the target DNA strand three nucleotides from the PAM sequence.

Figure (\PageIndex{31}\) below shows an expanded view of the ternary complex.

Mechanism of DNA binding and cleavage

The above figures do not speak to the mechanism of the binding processes that form the ternary complex. Kinetic and structural studies have been conducted to elucidate the mechanism of binding and cleavage and address the following questions:

- which binds first, the RNA or DNA?

- What are the consequences of the profound conformational changes on the formation of the ternary complex?

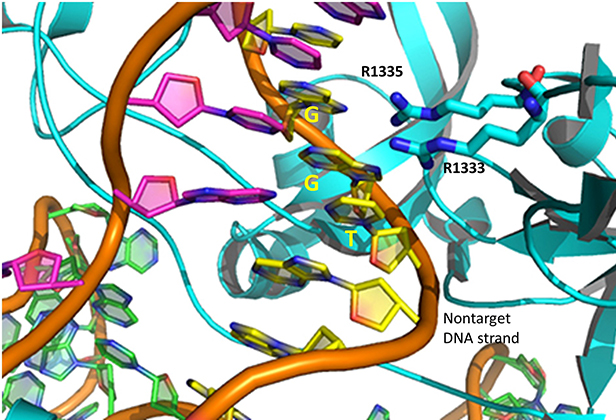

The specificity of target DNA binding depends both on enzyme:PAM DNA and enzyme:sgRNA (or tracr- and crRNA) interactions. It should seem improbable that the trinucleotide PAM DNA sequence (NGG in S. pyogenes), which interacts with a pair of arginines (R 1333, R 1335) through H-bonding, as shown in the images above, and other local sites in Cas 9 would provide the sole or even the majority of the binding interactions. Figure (\PageIndex{32}\) below shows the Args:PAM interaction (pdb code 4un3)

Hence it is most likely that RNA binds first. Indeed, it does with the tracRNA implicated in the recruitment of Cas and the crRNA providing specificity for target DNA binding. The resulting Cas9:RNA binary complex could then search the relevant DNA genome. That would include the DNA of the bacteriophage in viral infection or eukaryotic DNA if the CRISPR DNA operon with the genes for Cas 9 and a sg-RNA was transfected into the eukaryotic cell. After RNA binding, the enzyme would change conformation and allow loose DNA binding through Cas 9: PAM interactions.

Studies have shown that the apo form can also bind DNA, but it does so loosely and indiscriminately. It dissociates quickly and binding is affected by generic polyanions such as the glycosaminoglycan heparin, which indicates its nonspecific nature. Once bound, both off-target and target DNAs would then be surveyed. If a target DNA contained a PAM sequence, the complex would undergo another conformational change to position the HNH and Ruv nuclease catalytic residues and locally unwind the duplex DNA to make the blunt-end cuts.

Cas 9 binding to the PAM site would promote better interaction of the unwound DNA and the bound RNA. If no PAM was present, no catalytically-effective Cas 9:target DNA would form. This prevents off-site cleavage. These allosteric changes and controls are vital to the function of the endonuclease. Here are some findings that support this proposed mechanism:

- the conformation of apo Cas 9 is catalytically inactive;

- on binding RNA to form a binary complex, Cas 9 undergoes a dramatic conformational change, mostly in the REC lobe. However, on binding DNA in a nonspecific fashion, the conformational changes are much smaller. This suggests that most changes in conformation occur before DNA binding. In a way, RNA acts as an allosteric activator of the enzyme (as well as the major source of binding specificity to target DNA). Conformational changes can be determined directly by comparison of crystal structures or spectral techniques such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between two different attached fluorophores.

- Cas 9: RNA interactions lead to ordering of the region of the RNA that interacts with the DNA PAM sequence and adjacent deoxynucleotides (a "seed sequence"), allowing the Cas 9:RNA complex to scan and interact with potential DNA targets with PAM sequences;

- Once a PAM site is found, conformational changes lead to unwinding of the dsDNA, which allows heteroduplex formation between the crRNA and the target DNA strand;

- since Cas 9 recognizes a variety of DNA target sequences (but of course only a specific PAM sequence), the binding of the target sequence depends on the geometry, not the sequence, of the target DNA;

- since binding of off-target DNA to the Cas 9:RNA complex occurs but with very infrequent cleavage, binding and cleavage are very distinct steps;

- on specific DNA binding, the HNH catalytic site moves near to the sessile DNA bond site. Crystal structures show that the active site His is not sufficiently close to facilitate cleavage, suggesting that binding of a second metal ion (see below) may be necessary. Molecular dynamics studies show that the HNH domain is "remarkably plastic".

Figure (\PageIndex{33}\) below show an animation that illustrates the relative conformational changes going from the apo Cas 9 to the binary Cas 9:sgRNA complex to the ternary Cas 9: sgRNA: target DNA complex. The NUC catalytic domain is shown in light blue, the REC (receptor or RNA binding domain) in orange, sgRNA in red, and the target DNA in green. Note again that on binding RNA to form a binary complex, Cas 9 undergoes a dramatic conformational change, mostly in the REC lobe. The pdb protein sequences shown were aligned using pdbEfold.

A potential abbreviated catalytic mechanism for the Ruv nuclease domain is shown in Figure (\PageIndex{34}\) below. The red arrows indicate the second set of electron movements. His 983 acts as a general base to abstract a proton from the water making it a more potent nucleophile. An intermediate trigonal bipyramidal phospho-intermediate is formed, which, along with the preceding transition state, is stabilized by the proximal Mg2+ ion (an example of electrostatic or metal ion catalysis). The magnesium is positioned through its interaction with negatively charged carboxyl groups of Asp 10, Glu 762, and Asp 986.

A second metal ion might be recruited to the Ruv site to further facilitate the cleavage of the DNA. The HNH catalytic site has a structure (beta-beta-alpha) and conserved His in common with a class of nucleases that require one metal ion. In contrast, the Ruv catalytic site does not have this common secondary structural motif and has a critical histidine, both common features found in endonucleases that use two metal ions.

CRISPR and Eukaryotic Gene Editing

How could blunt-end cutting of both strands of DNA by Cas 9 lead to the holy grail of specific eukaryotic gene editing with no off-site effects? Cutting the DNA genome seems like a bad idea. It is potentially so bad that a myriad of DNA repair mechanisms has evolved to fix the cut. These include homologous recombination. If corrective DNA is supplied as well as the components of the CRISPR system, a cell could effectively add the corrective DNA after the double-stranded cut and repair a deleterious mutation. Consult a molecular biology textbook for more insight into homologous recombination.

Mutations in the PAM sequence prevent Cas9 nuclease activity. Hence the NGG PAM sequence is vital for the interactions and activities described above. This would seem to limit the utility of CRISPR-Cas 9 in eukaryotic gene editing until one realizes that the GG dinucleotide has a 5.2% frequency of occurrence in the human genome, which corresponds to over 160 million occurrences. Even then it might not occur in a desired gene target. Cas 9 nuclease from other bacteria extends the range of activity of the CRISPR/Cas system as they interact with other PAM sequences (NNAGAA and NGGNG for S. thermophilus and NGGNG for N. meningidtis). Likewise, mutations in the S. pyogenes PAM (NGG) have been made as well. A D1135E mutation retains but increases the specificity for the normal NGG PAM site. D1135V, R1335Q, and T1337R mutations alter the optimal PAM recognition site to NGAN or NGNG.

CRISPR editing can be easily used to knock out specific genes. In addition, if cells are transfected with a plasmid with many target sequences, the system can be used to edit multiple genes in one experiment. This would be very useful in studies of diseases linked to multiple genes. Since the cost of CRISPR reagents (plasmids, RNAs) is so inexpensive, and the specificity of editing is so high, the great excitement about CRISPR use for gene editing in human disease and for modification of plant and fungal genomes is warranted.

Other systems have been developed to specifically bind to a target DNA sequence and then cleave it. They typically contain a protein that binds to a specific DNA target and an associated endonuclease that cleaves within the target DNA site. Typical prokaryotic restriction enzymes bind to and cut at a specific nucleotide sequence (for example Eco R1 cleaves at G/AATTC palindromic sequences) to form sticky ends. The protein itself binds to this DNA recognition site. Other examples are based on the structure of known transcription factors. Libraries of genetically engineered proteins with Zn finger DNA binding domains (designed for specific DNA target sequences) fused to endonucleases have been created for this purpose. Other examples are proteins called TALENs (transcription activator-like effector nucleases). These are fusion proteins containing a TAL effector DNA-binding domain and a nuclease. In each of these cases, a 3D-folded protein is the specific target DNA recognition molecule. Think how much easier it is to make in effect a 1D-DNA recognition element, a simple linear RNA sequence, which would adopt the correct 3D structure on the binding of its complementary target.

One major problem in the use of CRISPR for gene editing must be solved: how to get the CRISPR components in the correct cells in an organism. In effect, it's the same problem faced by small drug designers only the components are much larger. Ex vivo applications, when diseased cells are removed from the body, repaired by CRISPR, and then reinjected, are likely to have more success. In these cases, electroporation would allow the uptake of Cas 9 and the sg-RNA. In vivo therapy has included the use of adeno-associated viruses in which genes for Cas 9 and sg RNA could be encapsulated. This technique, used for other gene delivery systems, has the advantage of being tolerated immunologically. However, this system allows for continual gene expression which is undesirable for gene editing. After an initial "fix" of a mutant gene, continued expression of the CRISPR-Cas 9 genes would increase the chances for off-target cutting. A more recent approach is to deliver the mRNA in artificial lipid nanoparticles that can be taken into cells. Once free and translated into protein and sg RNA inside the cell, gene editing has a chance to occur before the RNA and protein are degraded.

7.4 References:

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 21). Nucleophile. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:39, April 26, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Nucleophile&oldid=952368939

- Oregon Institute of Technology (2019) Organic Chemistry II (Lund). In Libretexts. Retrieved 10:58 am, April 27, 2020 from: https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Oregon_Institute_of_Technology/OIT%3A_CHE_332_--_Organic_Chemistry_II_(Lund)

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 12). Bond cleavage. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:15, April 27, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bond_cleavage&oldid=950494652

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, February 24). Arrow pushing. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:25, April 27, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Arrow_pushing&oldid=942438883

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 16). Acid dissociation constant. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:48, April 27, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.phptitle=Acid_dissociation_constant&oldid=951313744

- Farmer, S., Reusch, W., Alexander, E., and Rahim, A. (2016) Organic Chemistry. Libretexts. Available at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Core/Organic_Chemistry

- Ball, et al. (2016) MAP: The Basics of GOB Chemistry. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Introductory_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Map%3A_The_Basics_of_GOB_Chemistry_(Ball_et_al.)/14%3A_Organic_Compounds_of_Oxygen/14.10%3A_Properties_of_Aldehydes_and_Ketones

- McMurray (2017) MAP: Organic Chemistry. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(McMurry)

- Soderburg (2015) Map: Organic Chemistry with a Biological Emphasis. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_With_a_Biological_Emphasis_(Soderberg)

- Ophardt, C. (2013) Biological Chemistry. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Core/Biological_Chemistry/Proteins/Case_Studies%3A_Proteins/Permanent_Hair_Wave

- Soderberg, T. (2016) Organic Chemistry with a Biological Emphasis. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_with_a_Biological_Emphasis_(Soderberg)

- Ball, et al. (2016) MAP: The Basics of General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Introductory_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Map%3A_The_Basics_of_GOB_Chemistry_(Ball_et_al.)

- Clark, J. (2017) Organic Chemistry. Libretexts. Available at:https://chem.libretexts.org/Core/Organic_Chemistry/Amides/Reactivity_of_Amides/Polyamides

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018, December 28). Metabolism. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19:28, December 29, 2018, fromen.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Metabolism&oldid=875751739

- Ball, Hill, and Scott. (2012) Enzyme Activity, section 18.7 from the book Introduction to Chemistry: General, Organic and Biological (v1.0) retrieved on Dec 31, 2018 fromhttps://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/introduction-to-chemistry-general-organic-and-biological/s21-07-enzyme-activity.html

- Wikipedia contributors. (2018, November 29). Mechanism of action. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 05:00, January 1, 2019, fromen.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Mechanism_of_action&oldid=871201209

- Mótyán, J.A., Tóth, F., and Tőzsér, J. (2013) Research Applications of Proteolytic Enzymes in Molecular Biology. Biomolecules 3(4), 923-942; https://doi.org/10.3390/biom3040923

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 11). Adenylate kinase. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 19:28, May 4, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Adenylate_kinase&oldid=950311736

- Ahern, K., Rajagopal, I., and Tan, T. (2019) Biochemistry Free and Easy. Available at Oregon State University (http://biochem.science.oregonstate.edu/content/biochemistry-free-and-easy) and Libretexts (https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Biochemistry/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Free_For_All_(Ahern%2C_Rajagopal%2C_and_Tan)/04%3A_Catalysis/4.03%3A_Mechanisms_of_Catalysis)

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 16). Serine protease. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:32, May 6, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Serine_protease&oldid=951309456

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 16). Restriction enzyme. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:12, May 16, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Restriction_enzyme&oldid=951351229

- Pingoud, A., Wilson, G.G., and Wende, W. (2014) Type II restriction endonucleases - a historical perspective and more. Nuc Acids Res 42(12)7489-7527. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4081073/pdf/gku447.pdf

- Wikipedia contributors. (2019, July 25). BglII. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20:48, May 16, 2020, from en.Wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BglII&oldid=907885716

- De la Peña, M, GarcÍa-Robles, I., and Cervera, A. (2017) The Hammerhead Ribozyme: A Long History for a Short RNA. Molecules 22(1):78. Retrieved from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/22/1/78/htm

- Jakubowski, H. (2019) Biochemistry Online. Libretexts. Available at: https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Biochemistry/Book%3A_Biochemistry_Online_(Jakubowski)