7.4: The Sugar Code and Lectin Decoding

- Page ID

- 14958

Introduction

By now, you should be convinced that the structures of glycans are extraordinarily complex and, in many ways, much more complicated than proteins and nucleic acids. Their structure diversity is staggering, given the number of different sugar monomers, stereocenters, linkages, lengths, conformers, dynamic flexibility and chemical modifications. Yet evolution has allowed this astronomical diversity, which must serve more than just simple functions such as protection of proteins from degradation, to pick one example. Much of the diversity derives from the lack of an equivalent genetic code for glycan synthesis.

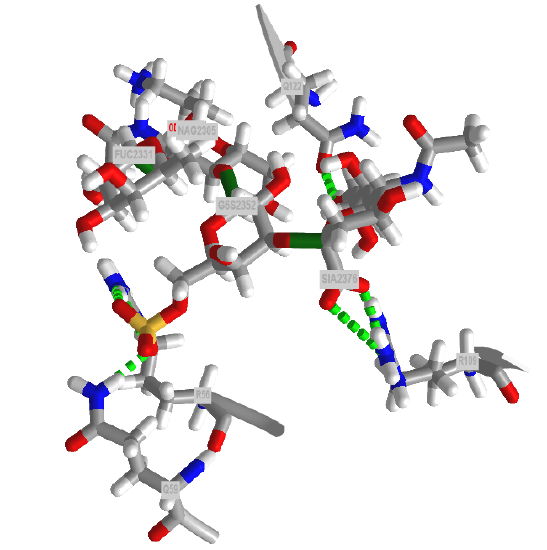

Since all events in biology start with a binding interaction, let's ponder the binding interaction of glycans with partner "ligands" such as proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, etc. A binding site on a glycan could be a single monosaccharide to a much larger and more complex interface. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of one of the few glycoproteins with pdb coordinates, the unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gp120 core glycoprotein (3fus).

V2.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=515&height=350)

The protein surface is shown in ivory and the glycans are shown in color sticks with the correct symbolic color-coded spheres or cubes around them.

Now let's convert in our imagination an image file showing one face of the protein to a black and white QR code as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Computers can recognize information encoded in the QR codes and decode them into another form of information, such as a menu at a restaurant. Likewise, organisms have evolved "readers" to decode the glycan code written by enzymes (glycan synthases, hydrolases, and modifying enzymes). The glycan code is written onto the 3D-surfaces of polysaccharides, glycoproteins, glycolipids, and proteoglycans. It should be no surprise that the biological readers of the glycan code are mostly proteins, which locate and bind to the correct "QR" code displayed on the surface of glycan.

Luckily, the QR code metaphor for the glycan code is a bit exaggerated since the readers of the glycan code, glycan-binding proteins, seem to recognize just small sections of a glycan. They can be compared to protein antibodies that bind to foreign molecules such as proteins. The binding site on a foreign protein recognized by an antibody is called an epitope. Epitopes can be continuous (linear) stretches of the foreign protein sequence, or discontinuous (conformational), made of some continuous stretches of amino acid and some further away in the sequence but close in the 3D folded protein. The average continuous epitope is often 5-6 amino acids long. Yet that might be an underestimation since an analysis of all contact residues (within a conservative 4 A° distance) for target proteins and their bound antibodies found in the Protein Data Bank is around 18-19 amino each (Stave and Lindpaintner). Glycan-binding proteins presumably also bind a mixture of continuous and discontinuous glycan sequences. Linear one would be much easier to determine and study.

Now, let's explore the family of these glycan-binding proteins (GBP), the readers of the glycan code.

Glycan-Binding Proteins (GBPs)

There appear to be nine types of glycan-binding proteins (GBPs). These include nonenveloped capsid virus GBPs,enveloped-virus GBPs (ex. influenza and coronaviruses), eukaryotic microbial GBPs (ex yeast), and bacterial toxin GBPs (ex botulinum toxin). Bacterial adhesins (parts of organelles like flagella), lectins (soluble proteins) and lectin domain-containing proteins are also examples of glycan-binding proteins (GBP). We will discuss in more detail three other types, C-type lectins, galectins, and siglecs.

In the broadest sense, if a lectin is a protein that binds a specific carbohydrate motif (i.e a glycan code) without modifying the motif, then any glycan-binding protein could be called a lectin. This would exclude enzymes that synthesize, degrade or modify glycans, as well as antibodies that would recognize foreign or self glycan sequences. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) below shows some lectins and their target glycan ligand from plants, animals, viruses and bacteria.

| Lectin Family/Lectin | Abbreviation | Ligand(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Plants | ||

| Concanavalin A | ConA | Man α1- OCH3 |

| Griffonia simplicifolia lectin 4 | GS4 | Lewis b (Leb) tetrasaccharide |

| Wheat germ agglutinin | WGA | Ner5Ac(α 2,3)Gal(β 1,4)GlcGlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc |

| Ricin | Gal(β 1,4)Glc | |

| Animals | ||

| Galectin-1 | Gal(β 1,4)Glc | |

| Mannose-binding protein | MBP-A | High Mannose Octasaccahride |

| Viral | ||

| Influenza Virus hemagglutinin | HA | Neu5Ac(α 2,6)Gal(β1,4)Glc |

| Polyoma virus protein 1 | VP1 | Neu5Ac(α 2,3)Gal(β1,4)Glc |

| Bacterial | ||

| Enterotoxin | LT | Gal |

| Cholera toxin | CT | GM1 pentasaccharide |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Lectin families and their ligands.

In animals, lectins facilitate cell-cell interactions by forming multiple, but weak interactions (also called multivalent interactions) between the protein and many sugars on the ligand to which it binds.

Now let's consider the other three classes of glycan-binding proteins (or lectins), C-type lectins, galectins, and siglecs in more detail. Focus on the very different structures of the carbohydrate-binding domains.

C-Type Lectins

C-Type lectins comprise the largest number of glycan-binding proteins. These proteins have a glycan or carbohydrate recognition domain that depends on the Ca2+ ion. They bind self glycans as well as those on pathogens, which can target viruses to specific cells. Many are on the surface of immune cells. They have an N-terminal glycan-binding domain, also called a C-lectin (CLECT) domain or a carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD). However, some proteins with the domain do not appear to bind either Ca2+ or glycans. They serve as adhesion molecules and are also involved in cell signaling. Some residues in the lectin binding domain appear critical for binding lectins. These include an EPN motif, which interacts with Man, GlcNAc, Fuc, and Glc) and a WND motif involved in binding to Gal and GalNAc.

Let's look now at one example of a C-type lectin, the selectins.

P-Selectins

These are involved in the interaction of immune cells in the blood with endothelial cells that line the blood vessel wall. Think of the challenges an immune cell faces as it moves from the blood into a tissue where an infection might occur! Blood flow in vessels at a rate inversely proportional to the total cross-sectional area of the blood vessel. That rate is about 5-20 cm/sec in arteries, 1.5-7 cm/sec in veins and about 1 mm/sec (1000 μm)/sec) in capillaries. Assuming an average diameter of 10 μm for a lymphocyte, the cell would move about 100 cell lengths per second. An equivalent speed for a human with an arm span of 6 feet (approximately fitting into a circle of diameter = 6 feet as drawn by Leonardo da Vinci) would be around 600 feet/second. The cell must go from its typical circulating speeds to a stop before it can move through the blood vessel wall into tissues. Nature has solved this by providing a way to slow down the moving cell until its final capture. The cells roll along the endothelial cells, making transient low-affinity interactions, which slow it down enough until high-affinity ones effectively stop it (unless it dissociates first).

Also, you wouldn't want immune cells to stop and move into tissue in the absence of an infection signaled by mediator molecules. Another problem solved! P-selections are stored in the intracellular granules of platelets (the source of the name P-selectin) and endothelial cells so moving immune cells are not spuriously captured in the absence of some signal. In the presence of the right chemical signal, endothelial and platelets get active and P-selectin is transported rapidly to the cell surface where "capture" occurs before the cell can move into the underlying tissue. P-selectin mediates the first transient interactions and subsequent rolling of immune cells on activated platelets and endothelial cells.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) is a video animating the rolling and "capture" of a lymphocyte by endothelial cells. (See the video for the reference.) Note that cancer cells also can move through the endothelial cells of blood vessels in the process of forming metastases.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Video animation of a lymphyocyte rolling and being captured by endothelial cells lining blood vessel walls

P-selectins hence are receptors for molecules on immune cells. They bind Ca2+ ions, which helps create an active conformation. Their binding ligands are glycan codes and nearby sections of protein connected to the glycan. The glycan ligand on the surface of a circulating immune cell is the sialyl-Lewis X (SiaLewX) glycan or a derivative of it. One of the immune membrane proteins with SiaLewX is the P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1, the gene name), also called SELPLG. It mediates rapid rolling of leukocyte rolling over vascular surfaces during the initial steps in inflammation through interaction with SELPLG"

P-selectin is a mediator of cell adhesion (to other cells). As such it could also be classified as an adhesion protein. The three main types of selectins:

- L-selectins: found on leukocytes ("white" blood cells that are circulating immune cells).

- P-selectins: found on activated platelets (which can aggregate to form a type of blood clot) and activated endothelial cells. Activation occurs during the inflammatory response which can lead to the quick movement of pre-formed selectins stored within the cytoplasm to the membrane. In addition, their expression can be induced.

- E-selectins: found on activated endothelial cells only after the cells have been induced to form them by certain immune hormones called cytokines released by immune cells during an inflammatory response.

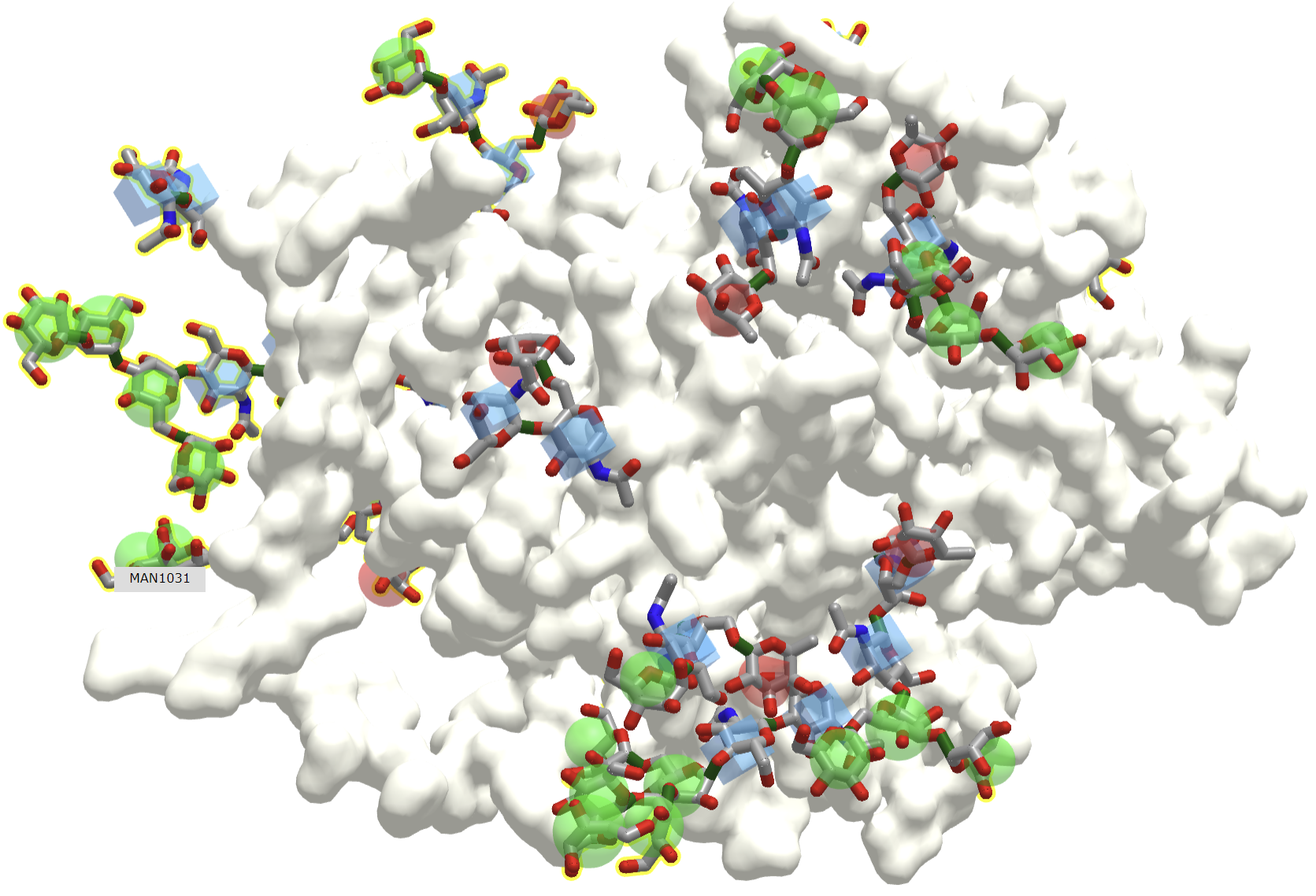

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the domain structure of human P-selectin.

It contains an N-terminal C-Lectin (CLECT) domain, which is also called the carbohydrate-recognition domain (CRDs) or the C-type lectin domain (CTLD). In addition, it has an epidermal growth factor domain (EGF), 9 complement control protein (CCP) domains and the blue transmembrane domain.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows the structure of the SLewx glycan along with its symbol nomenclature for glycans (SNFG) representation.

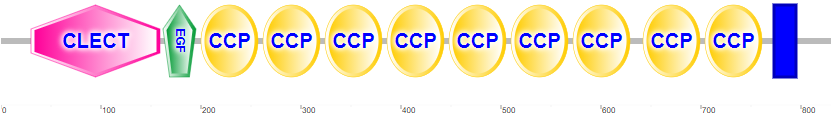

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the crystal structure of P-selectin lectin/EGF domains complexed with SLeX (1g1r) to which P-selectin binds with weak affinity. Fucose interacts with the Ca2+ ion. The glycan interacts with the CLECT domain.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=401&height=262)

SLewx is not present in isolation but rather attached to a membrane protein on an immune cell, which serves as a ligand for the P-selectin on activated endothelial cells or platelet. (The SLewx can also be part of a glycolipid.) Now let's contrast the interactions of the P-selectin LE domain with "naked" SLewx with those present between P-selectin LE with a higher affinity natural binding ligand, human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 (PSGL-1), an immune cell integral membrane protein. PSGL-1 is expressed on neutrophils, monocytes and most lymphocytes. The P-selectin:PSGL-1 complex has a much lower KD (higher affinity compared to binding of the unmodified SLeX (1g1s). PSGL-1 is a disulfide-linked homodimer. When sulfated on a specific Tyr (48) the protein displays high affinity for P-selectin. In contrast, when sulfated on a different Tyr (51), it displays high affinity for L-selectin instead

The SLexX type glycan O-linked to the peptide is a bit more complicated than the simple SLexX ligand as it is connected to a protein through an O-linked bond at a threonine. The SNFG is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

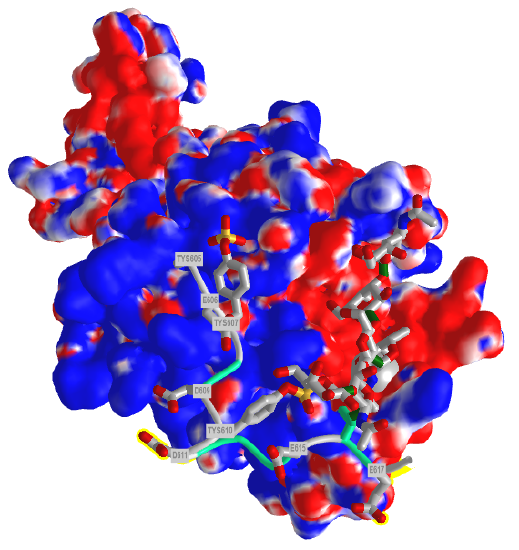

The crystal structure of a trisulfated, SLewx-modified peptide from the N terminal region of PSGL-1 (1G1S) bound to P-selectin lectin and EGF domains (P-LE) has been solved. Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model which shows some of the interactions between the PSGL-1 peptide (green backbone) and P-LE (magenta backbone).

In the crystal structure, the peptide from the P-selectin ligand (which again is a membrane protein) contains 3 sulfated tyrosine residues (605, 607, and 610) which correspond to amino acids 5, 7, and 10 in the peptide). No electron density for the side chain of Tyr 605 was seen. Tyr 607 binds through multiple interactions to the P-selectin LE domain, and is most likely responsible for the high-affinity interaction of P-selectin with the P-selectin glycoprotein ligand (again represented by the green chain). In contrast, Tyr 610 interacts through an intermediary water molecule with the glycan SLexX of the peptide.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows the electrostatic surface potential map of one of the dimers of the P-select LE domains. Blue represents positive potential and red negative. The backbone of the P-selectin ligand peptide is shown in green with all of the negatively charged side chains (Tyr, Asp and Glu) shown in stick with CPK colors. Note that these amino acids are all bound in blue (positive) regions of P-selection. The glycan portion attached to the peptide (stick, CPK color) is positioned mostly over negative potential, allowing hydrogen bonding between the hydrogen bond donors of sugar OHs with the protein.

You could surmise that the blue region of positive potential could also bind other strongly negatively charged ligands (such as heparin and other glycosaminoglycans) which could inhibit the function of this protein as it would prevent binding of the PSGL-1.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model which shows the surface electrostatic potential of the P-selectin Lectin/EGF domains and bound PSGL-1 peptide

The blue represents positive potential and the red negative. The backbone of the P-selectin ligand peptide is shown in green with all of the negatively charged side chains (Tys, Asp and Glu) shown in stick with CPK colors.

There are also nonpolar interactions not shown in the figure and model above. The aromatic ring of Tyr 607 (7) interacts with the nonpolar parts of a Ser (-CH2) and Lys (-CH2)4 side chains and the ring of Tys 610 (10) interacts with two leucine side chains.

The selectins are also part of a class of molecules called adhesion molecules. As described for the selectins, adhesion molecules contain

- an extracellular CHO binding domain (the lectin domain), which mediates binding to adjacent cells or to the extracellular matrix;

- a transmembrane domain;

- and a cytoplasmic domain which often interacts with the cytoskeleton within the cell.

This initial binding mediated by selectin-CHO interactions activates the expression of another adhesion molecule on the leukocyte, integrin, a heterodimer with an a and b chain. These cause strong leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions, leading to the movement of the leukocytes through the vessel wall. Other classes of adhesion molecules (in addition to selectins and integrins) are cadherins (calcium-dependent adhesion molecules), and the immunoglobulin-like superfamily (ICAM1, ICAM2, VCAM). VCAM (Vascular Adhesion Molecule) binds to integrin expressed on activated lymphocytes, leading to the passage of the lymphocyte from the lumen of the vessel into the tissues. Integrins appear to bind proteins in the extracellular matrix through RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) and also through LDV (Leu-Asp-Val) motifs on the proteins, including fibronectin (RGD), thrombospondin (RGD & LDV), fibrinogen (RGD & LDV), van Willebrand Factor (RGD), vitronectin (RGD). They also bind other matrix proteins with an "alpha domain" including collagen and laminin. Integrin/Adhesion molecule interactions involve protein/protein interactions.

A fertilized egg (in the blastocyst stage which is ready for implantation in the uterine cell wall) express L-selectin which allows a low affinity (rolling-type) interaction of the fertilized egg with the uterine epithelial cells. These cells expressed the CHO ligands on their surface which bind to the L-selectin on the blastocyst. The CHO ligands are only transiently expressed on the surface of the epithelial cells of the uterus, presumably only when the uterus is primed for implantation. After the initial interaction of the blastocyst and epithelial cells, further expression of integrins on the blastocyst surface might result. Problems in any of these molecular steps could result in infertility. Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) shows. endothelial cell/leukocyte Interactions mediated through selectins, integrins, and ICAMs.

Post-translational modifications of protein modification (like glycosylation) can confer new binding and biological functions to a protein. Site-directed mutagenesis can be used to replace surface amino acids with cysteine or methionine with nonnatural amino acid analogs that contain azide or alkyne groups. These modified groups could then direct the location of chemical modifying reagents (such as sugars) to these sites. A protein completely unrelated to PSGL-1 has been selectively modified using this approach to contain covalently attached glycans and sulfated tyrosine side chain. The unrelated protein bound to P-selectin.

Mannose Receptor.

What do you do with a protein that no longer has the correct structure(s) to perform its designed function(s). Proteins, as with any molecule, undergo chemical changes during their biological lifetime. They must be recognized as aberrant and then removed from "service", ultimately being degraded into component amino acids for reuse. There are no repair enzymes for proteins as for DNA. One modification that changes glycoproteins and signals the need for their removal is the removal of terminal sialic acid residue, forming asialoglycoproteins, whose glycans end in galactose, as you can envision from Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) which shows a typical structure of a N-linked glycoprotein.

The asialoglycoprotein receptor, a member of the C-Type lectin family, is a transmembrane protein, which binds terminal galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine sugars on the end of circulating asialoglycoproteins, leading to their endocytosis into the cell. It is expressed on the surface of hepatocytes (liver cells). Receptors of this type are also called scavenger receptors as they remove proteins from circulation.

The mannose receptor (also called CD206), also expressed in liver endothelial cells, is another C-Type lectin involved in binding and removal of glycoproteins from the circulation. It binds both sulfated and non-sulfated glycans. It also is a receptor that allows binding and phagocytosis of bacterial and fungal pathogens by a type of immune cells called macrophages and dendritic cells. Unfortunately, tumor cells can use the same process for uptake into macrophages, leading to the promotion of tumor cell growth. The protein binds and scavenges sulfated glycoprotein hormones, mannose-bearing glycoproteins released during inflammation, lysosomal enzymes released from cells on injury and fragments of collagen.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows the domain structure of the human mannose receptor.

Given the large number of CLECT domains, you might surmise that this protein could bind a number of different target glycans from both self and pathogens. What is different about the domain structure compared to P-selectin is the presence of an N-terminal Ricin and a Fibronectin type 2 (FN2) domain. The FN2 domain has two cystines from the 4 conserved cysteines involved in disulfide bonds. What's so interesting about the mannose receptor is that it binds glycans both in the CLECT domains and in the FN2 domain.

Glycan binding at the CLECT domain: The CLECT domain binds targets containing mannose, fucose and N-acetylglucosamine with a preference for Man(α1,2)Man or fucose. Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model. of the CLECT 4 domain of the mannose receptor complexed with Man(α1,2)Man (7jue). Interactions of fucose lin ligands such as Lewis-a-trisaccharide strengthen the binding.

Man_(7jue).png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=332&height=265)

The receptor can bind a variety of glycans. Both mannose and N-acetylglucosamine interact with bound Ca2+ through equatorial OHs on carbon 3 and 4 of the ring while fucose uses OHs on carbon 2 and 3, or 3 and 4.

The interaction with fungal pathogens is obviously medically important. Fungi like yeast have an outer structure composed of a membrane bilayer and a mixture of glycans, which deploys an incredibly complex "glycan code" to host infected by them, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\).

Mannans, polymers of just mannose, differ widely in structure. Their main backbone can be DMan(α-1,6)DMan or DMan(β-1,4)DMan with many branches.

Glcyan binding at the FN2 (Cysteine-Rich) Domain (1FWU): The mannose receptor can also bind non-mannose sulfated glycans, such as 3-SO4-LEWIS(X), for which the SNFG representation is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\).

The mannose receptor binds this glycan, which does not even contain mannose, through the FN2 domain (which contains four disulfide bonds) and not through the CLECT calcium-dependent carbohydrate-binding domain. Hence the protein can bind both sulfated and nonsulfated glycans.

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the complex of the FN2 domain of the mannose receptor with the non-mannose containing 3-SO4-LEWIS(X) glycan (1fwu).

_glycan.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=327&height=271)

Look at the number of CLECT domains in the domain structure diagram for the mannose receptor above. Along with interactions of sulfated glycans at the FN2 domain, these would enable the binding of widely diverse glycan structures. Reported ligands for the mannose receptor include those with high mannose content released during inflammation (lysosomal hydrolases, collagen peptides, and tissue plasminogen activator), and sulfated ones (including the pituitary hormones lutropin and thyrotropin.

Galectins

This family of glycan-binding proteins contains a common carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) of about 130 amino acids, which bind Galβ1,3GlcNAc or Galβ1,4GlcNAc disaccharides (hence the name galectins) as well as other glycan motifs . They are expressed in almost all cells and multicelluar organisms. There are 15 different types, grouped together in how the CRD is functionally expressed (as dimers, tandem repeats, or chimeras), as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\). The figure also shows their role in cancer biology.

The carbohydrate-binding domain of the galactins has a jellyroll-like protein architecture with two anti-parallel β-sheets forming a β-sandwich.

Galectin I

This protein is secreted and is found in the extracellular matrix, as well as in the cytoplasm. It induces apoptosis in T-cells. It binds beta-galactosides as well as other glycans. The main ligand of galectin-1 has a Galβ1-4GlcNAc (or LacNAc) structure. Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of Human Galectin-1 in Complex with Type 1 N-acetyllactosamine (Gal(β1,3)GlcNAc), which binds less tightly than Galβ1,4GlcNAc (Type 2)(4XBL)

GlcNAc).png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=454&height=259)

A comparison of the crystal structures shows different phi/psi angles for bound Type I (135°) versus the more tightly bound Type 2 (-108°), which shows the nuance in binding conformations in the interactions of glycans with glycan-binding proteins.

Siglecs

The proteins are sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin (Ig)-like lectins found on immune cells like basophils, macrophages, mast cells and eosinophils. One type (Siglec-4)is found in myelinated structures in the central and peripheral nervous systems. They all have an N-terminal extracellular immunoglobulin domain (abbreviated as IG or V-Set) and a differing number of IG-like domains, also called C2-set Ig domains. The glycan binding epitope recognized by Siglecs are sialylated oligosaccharides on a section of the protein containing a conserved arginine. Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) compares the domain structures of the human Siglec family.

Here is one example of a Siglec.

Siglec-8

This protein is expressed on immune cells like basophil, mast cells and eosinophils. When activated by infection and prolonged inflammation, they release the contents of intracellular granules which have potent physiological effects that can lead to allergic and asthmatic responses. On infection and other inflammatory states, immune cytokines are released that in a signaling process lead to the release of sialoglycans that act as ligands, binding to the Siglec-8 on the surface of the immune cells. One type of sialoglycan released is mucins, which are very large glycoproteins with many 6′S sLex glycans attached. These "multivalent" glycan epitopes can bind to Siglec-8 lead to signaling in the cells and ultimate inhibition of cell function (including by death or apoptosis). The mucins in mucus (cross-linked mucins), which cover epithelial cells or airways, also act as a first line of defense as they can bind viruses through mulitple-contact (multivalent) binding sites, effectively trapping the viruses. The glycan structure recognized by Siglec-8 is sialic acid and sulfate (NeuAcα2-3[6S]Galβ1-4G[Fucα1-3]GlcNAc-). Given their role in inhibiting and inducing apoptosis in immune cell, the family of siglecs are likely involved as checkpoints, which are important in cancer and inflammatory conditions.

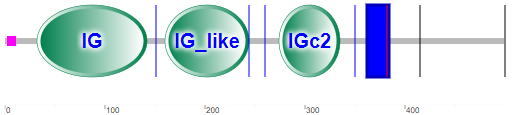

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) shows the domain structure of Siglec-8

Note that there is no CLECT domain, but rather immunoglobulin- (IG) or IG-like domains, which seems logical given their role in binding glycan "epitopes". The IG domain is also called the immunoglobulin V-set domain (V-Set). The blue rectangle represents the transmembrane domain (single helix). The cytoplasm contains a tyrosine-inhibitory motif (ITIM) involved in transducing the signal on binding 6′S sLex glycans to the IG domains.

As discussed above, humans lack a hydrolase gene necessary for the hydroxylation of Neu5Ac to Neu5Gc, which is found in chimps who possess the enzyme. Chimp's immune systems seem to confer protection from acquiring simian versiosn of AIDS, cirrhosis, and other diseases which humans acquire when they are infected with the human versions of the HIV virus, hepatitis B or C, or other viruses. These diseases and others associated with overactive T cells (rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, type-I diabetes) are not common in chimps. It turns out that there is a link between the type of sialic acid and the expression of siglecs that influences the difference for our disease propensity. Varki et al have shown that chimps and gorillas show much higher levels of expression of siglecs on T cells, which are critical regulatory and effector cells in the immune system. When siglecs on T cells are activated, T-cell responses are down-regulated. Although HIV virus ultimately kills T helper cells, the virus initially activates them on infection, leading to their proliferation and production of a larger number of cells for the virus to infect.

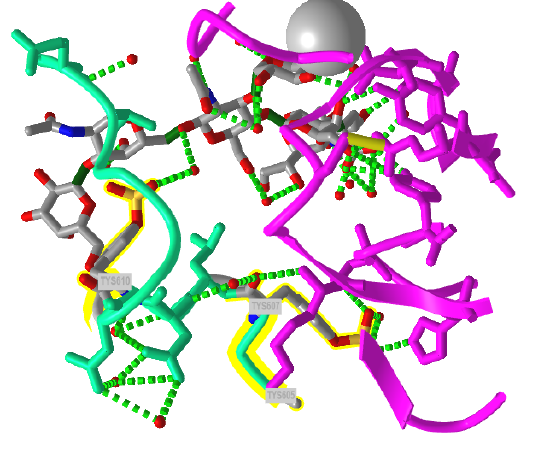

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of human Siglec-8 lectin domain in complex with 6'sulfo sialyl Lewisx (2N7B)