4.6: Protein Aggregates - Amyloids, Prions and Intracellular Granules

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 102257

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Search Fundamentals of Biochemistry

Introduction to Protein Aggregates

We have studied different types of protein aggregation, including aggregation of the native state (to form dimers, trimers, multimers, and filaments). We've also studied how misfolded proteins can aggregate and how a whole family of molecular chaperones help newly synthesized and misfolded proteins fold correctly. But what happens if a protein can fold two reasonably stable or metastable structures of starkly different conformation? A class of proteins called prions or amyloid proteins has this characteristic. their "alternative" conformation structures can bind to the "normal" structure and cause it to flip to the alternative conformation. This then can seed a continuation of the process which ends in the formation of large aggregates that are fibrillar in structure. This process leads to aberrant cell function and when it occurs in neurons can lead to a variety of brain diseases such as Alzheimer's Disease.

Protein aggregates complicate the lives of people who study protein folding in vitro and who try to express human proteins in prokaryotes like E. Coli in vivo, which often end up in large protein aggregates called inclusion bodies. Instead of viewing these aggregates as unwanted "junk", some study them avidly. It turns out that these aggregates are not as non-specific as earlier believed. In addition, an understanding of how and when they form will give us clues into the etiology and treatment of some of the most debilitating and feared diseases.

Specificity of Aggregate Formation

In the early 1970s it was shown that chymotrypsinogen could not be folded in vitro without aggregates forming. An intermediate was presumed to have formed that if present in high concentration would aggregate irreversibly instead of folding to the native state. Refolding of tryptophanase showed that it aggregated only with itself, suggesting specificity. In the 1980s, a single amino acid folding mutant was found in a viral protein. Both the normal and mutant viral proteins unfolded at high temperature, but only the mutant would aggregate at high temperatures, suggesting that aggregation could be programmed into or out of a gene. Also, a single amino acid change in bovine growth hormone completely prevented aggregation without affecting correct folding.

This knowledge of protein folding and aggregation was soon turned toward understanding several diseases in which protein aggregates were observed which either initiated or were associated with diseases. These protein aggregates were termed "amyloid deposits" and seemed to be associated and, perhaps causative of several neurodegenerative diseases. The name amyloid was first used by a German pathologist, Rudolf Virchow, who in 1853 described waxy tissue deposits associated with eosinophils (a type of immune cell). These deposits seemed to resemble starch (made of amylose and amylopectin) so he termed them amyloid. All known amyloid deposits are, however, composed of protein, not starch.

It now appears that these diseases are likely caused by improper protein folding and subsequent aggregation. Except in certain rare inherited diseases, the amyloid deposits are composed of normal wild-type proteins (not mutants), which seem to undergo conformational changes to form monomers, which catalyze the formation of more altered normal monomers into the altered form, which polymerize into fibrils. Sometimes, in inherited conditions, or when mutations appear in a specific protein, the amyloid protein deposits consist of the mutant protein. The proteins in these deposited fibers are composed predominantly of β sheets which are perpendicular to the fiber axis. In some cases, the monomeric "normal conformation" of the protein has little beta sheet structure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows a simplified model of how a normal protein with a "normal" conformation enriched in this case for illustration in alpha-helices can form fibrils of abnormal monomers which are highly enriched in beta sheets. These can self-associate to form large insoluble protein "amyloid" fibers. Note the green arrows representing beta-strands.

In the misfolded state, proteins have an increased propensity to oligomerize through the association of their metastable beta-sheet domains. These can convert into more stable beta-sheet states and the ensuing oligomers act as the nuclei for the subsequent elongation reaction, which leads to the formation of so-called protofibrils. The final amyloid fibril usually consists of a number of intertwined protofibrils.

Diseases of Protein Aggregates

We'll now describe a series of diseases that are caused by or highly associated with fibril formation from normal soluble proteins. For each one, we will present the best available structure of the amyloid fiber obtained mostly through cryo-EM. What's amazing is that at first glance all of the amyloid fiber structures have an astonishingly similar structural appearance. We present them not to be redundant but to illustrate how natural processes can render from a great diversity of protein structures a common structural and often lethal outcome. That the amyloid fibers are so structurally similar suggests that a common therapy to prevent their formation may be developed.

Familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy (FAP)

This affects 1/10,00 to 1/100,000 people. The monomer protein involved is called transthyretin (147 amino acids, MW 15,887), which normally exists in the blood as a homotetramer (a dimer of dimers). Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the structure of the dimer (6fxu). Note each monomer contains mostly beta structure. The protein binds L-thyroxine and around 40% of blood plasma transthyretin is bound to retinol-binding protein.

In mildly acid conditions in vitro, the equilibrium between tetramer and monomer is shifted to monomer, which can aggregate into fibrils. Monomer aggregation could be promoted by a possible transition to a molten globule (discussed previously with lactalbumin) like state. This has secondary structure but loosely-packed tertiary structure with more exposed hydrophobic groups. If the concentration is high enough the molten globules aggregate. In people with the disease, mutations in the protein destabilize the tetramer, pushing the equilibrium to the monomer, which presumably increases molten globule formation and aggregation. Specifically, Val30Met and Leu55Pro mutations promote the dissociation of the tetramer and the formation of aggregates. Conversely, Thr119Met inhibits tetramer dissociation. The aggregates deposit in the heart, lungs, kidney, etc, leading to death. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows a pictorial representation of how the transthyretin dimer could be stabilized to form monomers or dimers leading to fibril formation.

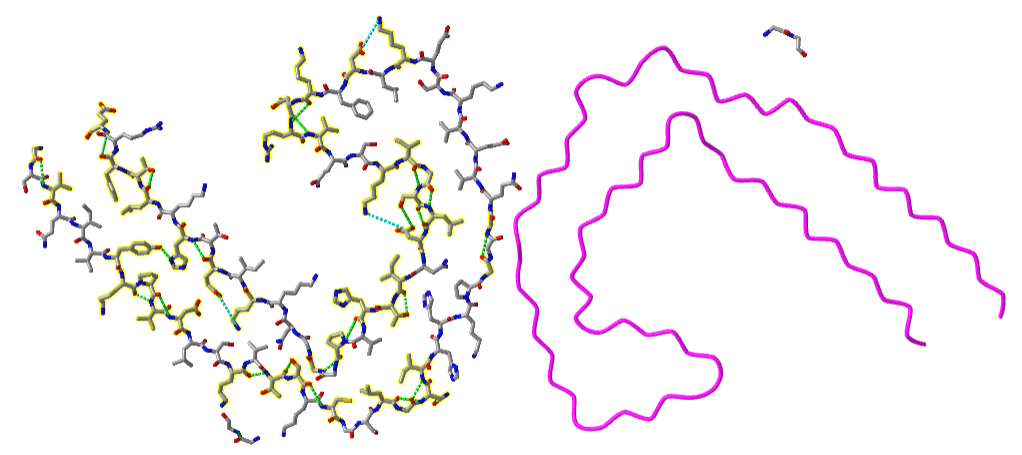

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the intramolecular hydrogen bonds bonds within monomers (-----) and intermolecular hydrogen bonds between monomers (-----) in the transthyretin dimer. We present this figure to remind readers that in all of the complex amyloid fibrillar structures presented below, the bulk of hydrogen bonds are "intermolecular" between adjacent monomers in their extended states (phi/psi angles consistent with beta-structure) within the fibrillar structure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of Cryo-EM structure of a transthyretin-derived amyloid fibril from a patient with hereditary ATTR amyloidosis (6SDZ). Each separate monomer is shown in a different color. The static image below shows arrows indicating beta strands, which form hydrogen bonds from the main chain amide Hs and carbonyls Os to another main chain atoms on an adjacent monomer.

Note the beautiful but unfortunately deadly array of adjacent extended monomeric chains (each colored differently) that form hydrogen bonds with adjacent extend monomers to stabilize the fibrillar structure.

Light Chain Amyloidosis - AL amyloidosis (amyloidosis from the light chain)

The light chain (MW approx 25,000) is a normal component of circulating immunoglobulin antibody (protein) molecules. Each contains two light and two heavy chains. We will discuss the structure of antibodies in detail in Chapter 5.5. Needless to say, antibodies are very diverse molecules. Antibodies can be generated by the immune system to recognize almost any foreign molecules. The light chains of antibodies hence are incredibly diverse and variable, although they all have two immunoglobulin domains. Each domain has about 110 amino acids containing two layers of β-sheets each with 3-5 antiparallel β-strands with a disulfide bond connecting the two layers so they start with significant beta structure in the monomeric form. The large diversity in light chains is generated in part by the recombination of gene fragments to produce individual light chains. Some variants of the light chains (λ1, λ2, λ3, λ6, and κ1) are associated with AL amyloidosis, a potentially fatal disease. Mutants in the light chain can cause a destabilization of the native state to a state similar to a molten globule, which then conformationally converts to a structure that aggregates into amyloid fibers. These can deposit in various tissues.

The pathway that a simple 25K monomer takes to produce such a complex but regular structure as shown above is must start with simple dimer formation between two monomers. Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the normal conformation of a λ6a light chain dimer (6mg4). The λ6a light chain variant is more prone to aggregate to form fibrils.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Full-length human lambda-6A light chain dimer showing IgG fold domains (6mg4). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...MNsiddm4RAdKn8

One light chain in the dimer is shown in blue, with one IgG fold domain in light blue and the other in dark blue. The other light in the dimer is shown in shades of magenta to show the two domains. Normally the light chains don't form dimers but rather associate with heavy chains to form full IgG antibodies. If not associated with a heavy chain, free light chains will form dimers, which can alter conformation and form amyloid fibrils.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the AL amyloid fibril from a lambda 3 light chain in conformation A (6Z1O). Each separate monomer is again shown in a different color.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): AL amyloid fibril from a lambda 3 light chain in conformation A (6Z1O). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...pSu2Nm714gvjh7

The Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows a comparison of the secondary structures of the native conformation of the light chain and those found in the two different fibrillar forms (A and B) of the amyloid fibrils (panel a). Remember that each light chain has two IgG domains, each having two sets of β-sheets containing 3-5 antiparallel β-strands).

Panel b shows the alignment of six fibrillar light chain proteins in conformation A. Panel c shows the trace of the backbones and the local environment of the side chains in a single light chain from the fibrillar A conformations. It shows cross-β-sheets interactions with parallel, hydrogen bonds across strands. Note the disulfide at connecting Cys 22 and Cys 87 on adjacent stands. The circles show surface side chains. Note that they are enriched in green (polar) and blue/red (basic/acidic) with some hydrophobic patches (example V10-L14). Some are pairs such as D24 and R28. Panel D shows the electrostatic surface of a single light chain from the fibrillar A conformation with red indicating negative and blue positive.

Alzheimers' Disease (AD)

This disease accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases. Brains in Alzheimer's patients have amyloid deposits of the amyloid beta (Aβ) protein as well as aggregates of a protein called tau. The origin of this disease is not fully resolved. Some believe aggregates of the amyloid beta protein cause the disease. Others suspect the role of tau in forming tau bundles. Still others suggest an infectious disease agent (more on that later). Irrespective of the fundamental cause, aggregates of the amyloid beta protein are neurotoxic and at minimum correlative if not causative of the disease.

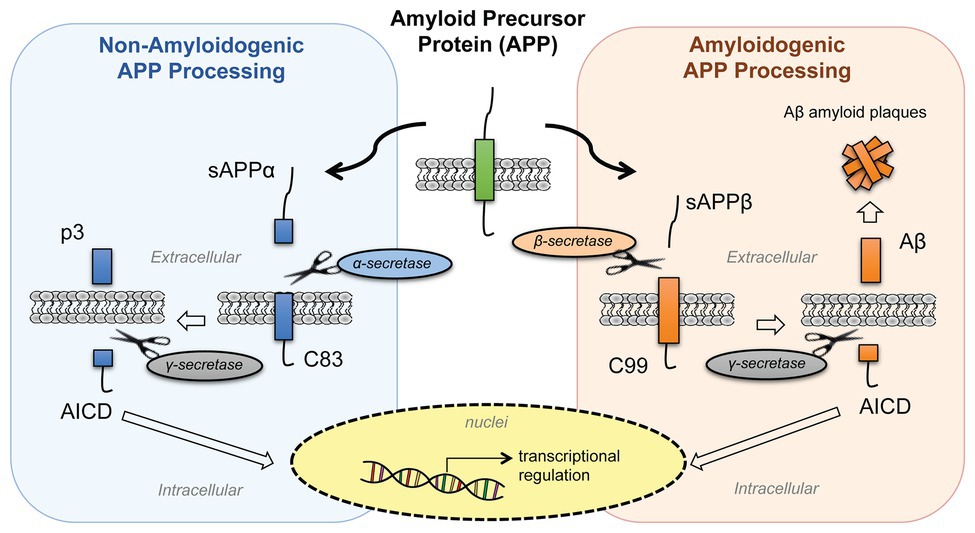

The amyloid aggregates in Alzheimer's start with a change in a monomeric protein normally found in the membrane of neurons. The protein, called β-amyloid precursor protein (BAPP or simply APP), is a transmembrane protein. A slightly truncated, soluble form is also found secreted from cells and is found in the extracellular fluid (such as cerebrospinal fluid and blood). The normal function of these APP proteins is not yet clear. An endoprotease cleaves a small 40-42 amino acid fragment from this protein named the amyloid beta (Aβ) protein. Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows the normal processing of the amyloid precursor protein APP (left) and the abnormal, amyloidogenic form (right).

In a "normal" processing pathway, the proteases α- and γ-secretase release two variant peptides, soluble amyloid precursor protein cleaved by α-secretase (sAPPα) and p3 fragments, into the extracellular environment. In the amyloidogenic processing pathway, β- and γ-secretases release soluble amyloid precursor protein cleaved by β-secretase (sAPPβ) and β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides. Both pathways release the same intracellular domain, AICD, which moves to the nucleus and acts as a transcription factor to regulate gene expression. The β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides aggregate to form the fibrillar aggregate plaque.

It is the amyloid beta (Aβ) protein or a mutant form of it that aggregates to form beta-sheet containing fibrils in Alzheimer's disease. The NMR solution structure of the monomer amyloid beta-peptide (1-42) is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\). Note the absence of any beta structure.

Several mutations in different proteins have been linked to Alzheimer's, but they all seem to increase the production or deposition or both of the amyloid beta protein. These deposited plaques are extracellular, and have been shown to cause neuronal damage. They are found in areas of the brain required for memory and cognition. The APP gene is found on chromosome 21, the same chromosome which is present in an extra copy (trisomy 21) in Downs Syndrome, whose symptoms include presenile dementia and amyloid plaques. Aggregate formation appears to be driven by increased expression of APP and hence amyloid beta protein. In addition, some mutants may serve to destabilize the amyloid beta protein, increasing its aggregation.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the prevalent amyloid-beta fibril structure from Alzheimer's disease brain tissue (6W0O).

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\): Amyloid-beta(1-40) fibril derived from Alzheimer's disease cortical tissue (6W0O). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...NZCX9sAhnFPiB6

The tau protein (758 amino acids, MW 78,928), which is much larger than the other proteins we discuss in this chapter, has also been implicated as a cause or factor in Alzheimer's Disease. It facilitates microtubule assembly and stability (see Chapter 5) along with other functions in neurons. Since its C-terminus binds microtubules in axons and the N-terminus binds the plasma membrane, it might link both. The cytoskeleton of neurons is disrupted in the neurons in Alzheimers' and in other neurodegenerative diseases patients. When tau tangles are involved, these diseases can also be termed tauopathies. One tauopathy is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) caused by repetitive head impacts (from contact sports or physical abuse) or concussions arising from explosions in combat. No full-length structure of tau has been determined. The structures of a predicted model of solution phase monomeric tau and tau fibers from the brain of patients with neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer's, CTE and Corticobasal Degeneration - CBD) are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

The predicted structure of the monmeric protein (using AlphaFold) is almost completely devoid of secondary structure. The structures of tau from the other tauopathies are similar but clearly distinct. In CBD tau fibers there are 4 microtubule-binding repeats (4R). Picks Disease, another tauopathy, has three repeats (3R) while taus in AD and CTE are 3R or 4R.

The fibril cores of tau in both CBD (Lys 274-Glu380, which contains the end of R1 and R2-R4) and Alzheimer's Disease (CD) contain around 13% glycine residue. These allow the main chain flexibility and intersheet packing to allow the large conformation changes necessary to adopt beta structures and fibril formation. Repeats of PGGG motif allow sharp turns or extended chains. Valine (around 10%) and isoleucine, leucine, and phenylalanine facilitate inter-sheet packing through induced dipole-induced dipole interactions as well as through the hydrophobic effect. Certain tau fibrils in CBD contain hydrophilic pockets that bind molecules yet to be elucidated that might seed the nucleation of fibrils. The cavity has three lysines and a histidine so the molecule with the pocket is probably linked to histidine might be a glycan or an ADP-ribose. In addition, recent evidence shows that different combinations of post-translational modification by ubiquitinylation and acetylation of lysines 311, 317, 321, 343, and 353 might lead to different tau fibril structures. CTE tau protein in tangles appears to be hyperphosphorylated.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a paired helical tau filament from Alzheimer's Disease human brain tissue (6VHL).

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): Paired helical filament of Tau (6VHL) (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...NHsZdhDJNentg9

Zoom into the interactive images to see the H bonds within one of the filaments. Note that the hydrogen bonds (green dotted lines) in the left filament are between side chains and not between backbone amide Hs and carbonyl Os. These are pointing above and below the plane of the backbone where they could interact with other of the chains above and below to create the multi-chain fibers seen in all of the examples above.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a singlet Tau fibril obtained from corticobasal degenerated human brain tissue (6VHA).

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Singlet Tau fibril from corticobasal degeneration human brain tissue (6VHA). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...Bbxr2Z1caGqnG8

The backbone of the C-terminal amino acid (367-380) of each of the three separate chains of the fibril is shown in CPK colors and hydrogen bonds between the strands that form the parallel beta strands are shown as green dashes.

Progress has been incredibly slow on ways to treat Alzheimer's. Most methods focus on reducing amyloid beta production and aggregation by finding small molecules that inhibit steps in its production, including secretase cleavage, and the resulting conformational steps necessary to produce amyloid fibers. But what if the amyloid aggregates are secondary to the primary cause? What if the overproduction of the amyloid beta protein was the brain's response to defend against the cause?

Lewy Bodies and Parkinson Disease

α-Synuclein (140 amino acids, MW 14,460) is expressed in the brain and in presynaptic terminals in the central nervous system and is involved in the regulation of neurotransmitter release and in the synaptic vesicles that hold them. Its aggregation is a cause or consequence of Parkinson's Disease and Lewy Body Dementia. It's found in the cytoplasm and the nucleus and is secreted as well. Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) shows an NMR solution structure (left) and AlphaFold-predicted structure (right) for this protein which in solutions is so disordered that no full crystal structure has been determined.

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of an amyloid fibril structure of alpha-synuclein determined by cryo-electron microscopy (6A6B). Two protofilaments with clearly Greek key topologies are shown.

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\): Amyloid fibril structure of alpha-synuclein determined by cryo-electron microscopy (6A6B). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...SbQq7fhFpQ9K4A

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) - Prion Diseases

Prion diseases are another set of brain diseases resulting from aggregates of monomers of the prion protein (PrPc). As with the examples above the aggregates form amyloid beta fibrils. The prion diseases include scrapie in sheep, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease), and in humans Creutzfeld-Jacob Disease (CJD), Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI), Gerstman-Straussler-Scheinker Syndrome, and Kuru (associated with cannibalism). In these fatal diseases, the brain, on autopsy, resembles a sponge with holes (hence the name spongiform). In contrast to the diseases described above, these diseases can be transmitted from one animal to another, but typically not between species. (However, consider the controversy with mad cow disease.) Also, the infectious agent can self-replicate in vivo. The logical conclusion is that a virus (slow-acting) is the causative agent. However, the infectious agent survives radiation, heat, chemical agents, and enzymes designed to kill viruses and their associated nucleic acids. Mathematical analyses suggested that the infectious agent in such diseases could be nothing more than a protein. Stanley B. Prusiner in the 80's isolated just such a protein which he named a prion, for proteinaceous infectious agent. In October 1997 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

The normal monomeric prion protein, PrPc (253 amino acids, MW 27,661), is highly conserved in mammals, and is widely expressed in embryogenesis. Expression is highest in the central nervous system. The normal function of the protein is still unclear. It is a physiological substrate to a particular membrane receptor (the Gpr 126 G protein-coupled receptor). Knocking out the gene shows that the normal protein is involved in synapse structure/function, myelination of neurons and circadian rhythms probably by acting as a transcription factor. It also helps regulate Cu2+ and Zn2+ levels in the central nervous system. The protein is cleaved and a 209 amino acid fragment is bound to the extracellular side of the neuron membrane-anchored by attachment of a lipid (GPI) anchor.

The protein N-terminal residues (23-124) are flexibleand are followed by residues 125-231 which are mostly alpha helical. There is a disulfide between Cys179 and Cys214. The PrPc (without the PI link) is water soluble, a monomer, protease-sensitive, and consists of around 45% alpha helix and 3% beta sheet. No full-length crystal structure of the protein has been determined given its highly disordered structure. The solution structure of residues 125-231 has been determined by NMR and the structure of the full protein has been modeled with Alpha Fold. These structures are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\).

The blue helices and gold loops in the computer model consists of the same amino acids (125-231) as the NMR solution model in the left hand side of Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

The problem in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE's) is that amyloid-like protein aggregates form, which are neurotoxic. The protein found in the plaques (in cases other than those that are inherited) has the same primary sequence as the PrPc but a different secondary and presumably tertiary structure. The protein found in the plaques, called the PrPsc (the scrapie form of the normal protein) is insoluble in aqueous solution, protease-resistant, and has a high beta sheet content (43%) and lower alpha helix content (30%) than the normal version of the protein PrPc.

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the cryo-EM structure of an amyloid fibril formed by full-length human prion protein (6LNI). Each line represents a PrPsc chain from amino acids 170-229,which is the core of the fibril.

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\): Cryo-EM structure of an amyloid fibril formed by full-length human prion protein. (6LNI) (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...ByT4rL33brHRY7

The aligned zig-zag lines clearly indicated beta strands aligned through hydrogen bonding the adjacent strands. The two alpha helices in the C-terminal domain become beta strands .

A genetic, inheritable form of the disease also exists, in which a mutant form of the PrPc occurs, whose normal structure is destabilized by the mutation. The aggregates caused by the mutant form of the disease are understandable in light of the other diseases which we discussed above. The question is how does the normal PrPc form PrPsc . Evidence shows that if radiolabeled PrP*c from scrapie-free cells is added to unlabeled PrPsc from scrapie-infected cells, the PrP*c is converted to PrP*sc! It appears that the PrPc protein has two forms not that much different in energy, one composed of mostly alpha helix and the other of beta sheet. A dimer of PrPc.PrPsc might form, which destabilizes the PrP*c causing a conformational shift to the PrPsc form, which would then aggregate. Exposure to the PrPsc form would then catalyze the conversion of normal PrPc to PrPsc . Hence, it would be transmissible by contact with just the PrPsc form of the protein. Likewise, species specificity could be explained if only dimers of PrPc.PrPsc formed from proteins of the same species could occur. The inherited form of the disease would be explained since the mutant form of the normal protein would more easily form the beta structure found in the aggregate.

It has recently been found that the very same mutation in PrPc, Asp178Asn can cause two different diseases - CJD and FFI. Which disease you get depends on if you have 1 of two naturally occurring, nonharmful variants at amino acid 129 of the normal PrPc gene. If you have a Met at that position and acquire the Asp178Asn mutation, you get CJD. If, on the other hand, you have a Val at amino acid 129 and acquire the Asp178Asn mutation, you get FFI. This disease was first observed in 1986 and has been reported in five families in the world. It occurs in the late 50's, equally in men and women. It is characterized by a progressive loss of the ability to sleep and disrupted circadian rhythms. The brain shows neuronal losses. It is known that amino acids 129 and 178 occur at the start of alpha helices, as predicted from propensity calculations. Chronic exposure to micromolar levels of synthetic fragment 106-126 of PrPc kills hippocampal neurons. This peptide also has the greatest tendency to aggregate synthetic PrPc peptides.

Kuru killed many members of the Fore tribe in New Guinea until the cannibalistic practice of eating dead relatives was stopped. Analysis of the genes for the prion protein in the Fore tribe and other ethnic groups in the world show two versions differing by just one amino acid in all people (remember that a single gene is represented in both maternal and paternal chromosomes. That these two forms exist throughout the world suggests that they have been selected for by evolution and confer some biological advantage. People who have just one form of the protein are more susceptible to the development of prion diseases. Mead and Collinge have shown that about 75% of older Fore women (who had lived through cannibalistic practices) had two different prion genes, compared to about 15% of women from other ethnic groups. This high percentage suggests that these women were protected from the disease, leading through natural selection to a high percentage of heterozygotes in this defined population. The general presence of two forms of the prion gene (which probably offers protection from prion disease) suggests that cannibalism might have been widespread in our early ancestors.

There appears to be one main difference between the formation of amyloid fibers from prion proteins and others such as mutant lysozymes. If you add mutant lysozyme to normal lysozyme, the amyloid fibers contain only the mutant protein. However, if you incubate mutant prion proteins with normal prions, the normal proteins become pathological.

Misfolding and Aggregation Summary

Recent work has shown the proteins considered to be completely harmless can generate misfolded intermediates that aggregate to produce pre-fibril structures that are toxic to cells. This process is usually prevented in the cell by the interaction of nascent forms of the proteins with chaperones, which sequester exposed hydrophobic patches and prevent aggregation. (Obviously, prion proteins and the others mentioned above are exceptions). Amyloid fibers (characterized by subunits with an abnormal amount of beta-structure) can be made from many different types of proteins as noted above. Is this property specific to just a handful of proteins, or is it more common than expected from the limited examples noted so far? The new studies show that when a bacterial protein HypF is incubated at pH 5.5 in the presence of trifluoroethanol, aggregates (but not fibrils) form with enhanced beta structure. These aggregates slowly form into fibrils characteristic of amyloid protein fibers. The early aggregates (before fibril formation) proved cytotoxic. Similar results were seen with dimers and trimers (prefibril states) of the amyloid-b peptide released from cultured neurons.

A diverse group of proteins that do not share significant secondary or tertiary structures can form amyloid-like protein aggregates. Even though their monomer forms share little in common, the insoluble amyloid aggregates have a common structure in which the monomer in the aggregates has significant beta structure with the strands running perpendicular to the aggregate axis. Since it has recently been shown that almost any protein, under the "right" set of conditions, can form such aggregates, the stabilizing feature of protein aggregates must be potentially found in any protein. Evidence suggests that it is the polypeptide backbone, and not the side chains, that are key in the formation of stable interstrand H-bonds in beta secondary structures in amyloid aggregates. In contrast, native, nonamyloid forms of normal proteins arise through specific interactions of unique side chain sequence and structure, which out-competes nonspecific interactions among backbone atoms found in amyloid structures. Nonspecific aggregation becomes more prevalent when buried hydrophobic side chains and buried main chain atoms become more solvent exposed. Such exposure occurs when native proteins form intermediate molten globule states when subjected to altered solvent conditions or when destabilizing mutants of the wild-type protein arise. Some mutations may alter the cooperativity of folding which would increase the fraction of nonnative protein states. Other mutations that decrease the charge on the protein or increase their hydrophobicity might enhance aggregation. In addition, chemical modifications to proteins (such as oxidation or deamination) might destabilize the native state, leading to the formation of the molten globule state. Once formed, this state may aggregate through sequestering exposed side chain hydrophobes or through inter-main chain H bond formation. Aggregate formation appears to proceed through the initial formation of soluble units (which may or not be more toxic to cells than the final aggregate). Aggregates are kinetically stable species. Since amyloid aggregates are cytotoxic and almost any protein can form them, albeit with different propensities, nature, through evolutionary selection, has presumably disfavored proteins with high tendencies to form such aggregates.

Clearly, accurate protein folding is required for cell viability. Aberrant protein folding clearly can be the cause of serious illness. Given the extraordinary nature of the task and its failure, the process governing protein folding must be highly regulated. Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) shows the steps that determine intracellular concentrations and locations of normal and aberrant protein structures.

Potential therapies for diseases of proteostasis include replacing aberrant proteins, shifting the equilibria toward active forms with small ligands, or modulating the pathways with agents that influence pathways such as signal transduction, transcription, translation, degradation, and translocation using molecules like siRNAs to modulate concentrations of chaperons, disaggregases, and signal pathways.

Binding, Intracellular Granules and Droplets

The above structures are fascinating aggregates of specific proteins. The aggregates are quite large. In Alzheimer's Disease, they vary from around 150-500 μm2, which would give a length of 12-22 μm if they were squares. In comparison, intracellular "granules" are much smaller with diameters from 200-500 nm or 0.2-0.5 μm. The term granule describes particles in cells that are just barely visible by light microscopy. Granules are found in many cells and mostly contain protein. Platelet granules contain many proteins involved in clotting. Pancreatic beta cell granules contain insulin for secretion. Other types of granules in germ-line cells are called various names such as dense bodies, perinuclear P granules in Caenorhabditis elegans, germinal granules in Xenopus laevis, chromatoid bodies in mice, and polar granules in Drosophila. The contains RNA as well as proteins. Those are often called ribonucleoprotein (RNP) granules. Plants and livers also contain starch (a carbohydrate) granules. The granules don't appear to be surrounded by a membrane. Rather they are just aggregates of proteins, or RNA and proteins. In Chapters 10 and 11, we will see analogous particles for lipids, nonpolar "insoluble" molecules that self-aggregate into micelles and membrane bilayers. Lipid droplets, which contain TAGs and cholesterol esters, in contrast to the granules mentioned above, are surrounded by a phospholipid monolayer with adsorbed protein. Maybe an understanding of the structure and properties of phase-separated granules can shed light on the aggregates formed in neurodegenerative diseases.

How do these granules form? What principle underlies the specificity of protein and RNA found in them? The aggregates are not toxic compared to the beta-amyloid aggregates discussed above. A quick review of the Cell Tutorial (scroll to bottom) shows granule formation can be caused by a classic "phase transition", not unlike gaseous water can self-associate through hydrogen bonds to form liquid drops, which can freeze with the formation of more hydrogen bonds to form solids. Soluble biomolecules in cells can reversibly aggregate through the summation of multiple, weak noncovalent interactions to form storage granules. This balance might be perturbed if storage granules aggregate further in a potentially irreversible process with health consequences as we saw in neurodegenerative diseases. Let's delve into new insights into the processes involved in droplet formation.

Imagine small amounts of a sparing soluble oil added to an aqueous solution. Initially, it is in solution, but at a higher concentration, induced dipole-induced dipole interactions and the “hydrophobic effect” would drive the oil out of the solution into liquid drops. This phase separation could also be called liquid-liquid demixing as two liquids (solubilized oil in water and separated oil drops) separate. from each other. This process has been shown to produce many types of non-membrane bound droplets (not to be confused with membrane-bound vesicles) in the cell.

This phenomenon has also been seen with intrinsically disordered proteins and proteins with such domains. These are characterized by amorphous structures with repeated, often positively charged amino acids and/or contain a limited number of different types of amino acids. An example of a protein with a domain that has low sequence complexity is the SP1 transcription factor, a DNA binding protein. One of its tranactivation domains is comprised of almost 20% glutamines with regions within it having even higher percent abundances. It has been estimated that up to 20% of eukaryotic proteins don't have a stable shape as they are in part intrinsically disordered and contain low complexity domains (LCDs). They are found in the N- and C-terminal ends of all mammalian intermediate filament proteins, almost all RNA binding proteins, lining the nuclear pore and in the cytoplasmic faces of mitochondrial, lysosomal, peroxisomal and Golgi integral membrane proteins. "They decorate both ends of all 75 intermediate filament proteins found in mammals, fill the central channel of nuclear pores, adorn almost all RNA-binding proteins, and occur on the cytoplasmic faces of integral membrane proteins associated with mitochondria, neuronal vesicles, peroxisomes, lysosomes, and the Golgi apparatus. They are the target of up to 3/4s of posttranslational modifications. LCDs hence appear to facilitate the promiscuous binding of a variety of proteins, especially those that lead to or remove covalent tags.

Under the right condition, these can aggregate and “precipitate” from the solution. What is the nature of the precipitate? It might have properties more like distinct liquid droplets so this process could be called liquid-liquid demixing.

Properties of demixed drops would include reduced rates of diffusion of material into an out of the drop, coupled movements of materials in the drop, and probable weak hydrophobic-dependent aggregation making drops sensitive to agents like detergents. Liquid-like diffusion inside the drop is observed as evident by the rapid recovery of fluorescence from partially photobleached internal components of the drop.

As with the formation of a crystalline solid from a liquid solution, the process must be seeded. For intrinsically disordered proteins, this process can be “catalyzed” by poly-(ADP-ribose), a nucleic acid-like polyanion. The negative charges would counter the positive charges in the disordered protein domain, which without neutralization, would interfere with protein/protein contacts necessary for aggregation/droplet formation and demixing. Aggregation in these cases may arise from hydrophobic interactions (even though hydrophobic side chains are underrepresented in the disordered domains).

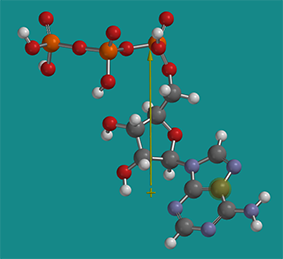

The solubility of proteins in cells is a fascinating topic in itself. High concentration of ATP (5 mM) in the cell actually helps to solubilize proteins. ATP is considered a hydrotrope. It’s a small molecule with a very distinct polar part (polyphosphate and ribose) and a more nonpolar part (the adenosine ring). Hence it acts sort of like a mini-detergent (an amphiphile) but it doesn’t form micelles. It does help stabilize more nonpolar parts of proteins in solution and has been shown to inhibit aggregate formation and also disaggregate some aggregates. Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) shows a nonprotonated form of energy-minimized ATP with its dipole moment shown as an arrow from + to - end. The dipole moment would only be larger if the ATP was deprotonated and had negative charges.

Biochemists also use the term gel (examples include polyacrylamide gel or fibrin blood clots which are chemically cross-linked) and a "gel" form of a bilayer (Chapter 10), when they wish to describe a structure that is neither clearly solid nor liquid. Structures like the cytoskeleton or the actin-myosin network would be examples of the latter.

Noncovalent gels would be characterized by the regulatable dissociation of subunits and hence short half-lives. A gel (either covalent or noncovalent) with a high-water content could be called a hydrogel which would contain hydrophilic components. An example would be RNA and protein-containing particles

RNA granules

Granules that contain RNA and proteins are called ribonucleoprotein bodies (RNPs) or RNA granules. Specific examples of these include cytoplasmic processing bodies, neuronal and germ granules, as well as nuclear Cajal bodies, nucleoli and nuclear dots/bodies). Some granules just contain proteins, including inclusion bodies with misfolded and aggregated proteins and those with active proteins involved in biosynthesis, including purinosome (for purine biosynthesis) and cellusomes (for cellulose degradation).

Another feature found in some neurodegenerative diseases is a trinucleotide repeat. In Fragile X syndrome, there 230-4000 repeats of the CGG codon in the noncoding parts of the genome, compared to less than 50 in the normal gene. In Huntington’s disease, the repeat CAG is found in the protein-coding part of the affected gene. The translated protein has a string of glutamines which probably causes protein aggregation. Specific proteins may also bind to the string of CAGs.

If the trinucleotide expansion is in the nonprotein-coding intronic DNA, deleterious effects are not associated with translated proteins but with the transcribed RNA in the nucleus. The intronic repeats would be spliced out of the primary RNA transcript. A CTG DNA repeat would produce a poly CUG containing RNAs (found in myotonic dystrophy), which could aggregate through non-perfect base pairing.

In vitro experiments show that small complexes are soluble, but as the size increases, a liquid-liquid demixing phase separation (or alternatively a liquid-gel transition) can occur, forming spherical droplets of RNA particles. This would explain the observation that pathologies occur above a certain repeat length. If misfolded proteins are also present, these particles might combine to form larger gels.

In the control experiment, when the repeats were scrambled, demixing and spherical particle formation were not observed. In an experiment similar to the addition of 1,6-hexanediol to intrinsically disordered proteins, if small antisense trinucleotide repeats, such as (CTG)8, which could interfere with the weak H bonds between G and C in the aggregates, were added, the size of RNA drops (foci) were reduced. In vivo experiments showed characteristic drop-like structures but only if the repeats were of sufficient size.

Researchers found that in vitro, RNA drop formation was inhibited by monovalent cations. In the presence of 0.1 M ammonium acetate, which permeates cells without affecting pH, CAG RNA droplets in vitro disappeared.

Aggregation of mRNA might be one way to regulate its translation and hence indirectly regulate gene activity. There are advantages to regulating the translation of a protein from mRNA, especially if the "activity" of the mRNA could be dynamically regulated. This would be useful if new protein synthesis was immediately required. Hence one way to regulate mRNA activity (other than degradation) is through reversible aggregation.

Protein drops and granules

The cytoskeletal proteins actin and tubulin (heterodimer of alpha and beta chains) can exist in soluble (by analogy to water gaseous) states or in condensed, filamentous states (actin filaments and microtubules respectively). GTP hydrolysis is required for tubulin formation. Actin binds ATP which is necessary for filament formation but ATP cleavage is required for depolymerization. Hence nucleotide binding/hydrolysis regulates the filament equilibrium which differentiates from simple phase changes such as in water.

Since only certain proteins form granules, they must have similar structural features that facilitate reversible binding interactions. These proteins have multiple, weak-binding sites, but if they act collectively provide multivalent (multiple) binding interactions that allow robust but not irreversible granule formation. Here are some characteristics of proteins found in granules:

- the protein NCK has 3 repeated domains (SH3) that bind to proline-rich motifs (PRMs) in the protein NWASP. These proteins are involved in actin polymerization. In high concentrations they precipitate from the solution and coalesce to form larger droplets;

- repeating interaction domains are widely found especially among RNA-binding proteins;

- some proteins contain Phe-Gly (FG) repeats separated by hydrophilic amino acids in portions of the protein that are intrinsically disordered.

- a biotinylated derivative of 5-aryl-isoxazole-3-carboxyamide (Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)) precipitates proteins, which are enriched in those that bind RNA (RBPs). In general, the precipitate proteins were intrinsically disordered and characterized by low complexity sequences (LCS). One such example contained 27 repeats of the tripeptide sequence (G/S)Y(G/S). The proteins could also form hydrogels (made of hydrophilic polymers and crosslinks) and transition between soluble and gel phases with extensive hydrogen bond networks. The hydrogel gel phase gave x-ray diffraction patterns similar to beta structure-enriched amyloid proteins. Short-range, weak interactions between LCS might then drive reversible condensation to gel-like granule states characterized by extensive hydrogen bonding (again similar to hydrogen bonding on ice formation). If this process goes awry, more continued and irreversible formation of a solid fibril (as seen in neurodegenerative diseases) might occur from the hydrogel state;

- RNAs appear in granules when proteins bind them through their RNA binding domains, which interact through low complexity sequences leading to phase separation and hydrogel-like formation of granules. Around 500 RNA binding proteins have been found in the human RNA interactome. They are enriched in LCSs and have more tyrosines than average proteins in the whole proteome in which the Tyr are often found in the (G/S)Y(G/S) motif. Phosphorylation of tyrosines (Y) in LCS may decrease association and hydrogel stability.

Given that so many neurodegenerative diseases are associated with unfolded/misfolded protein aggregates, the high protein concentrations in protein-containing liquid drops might pose problems to cells. If high enough, the equilibrium might progress from the liquid drop to a solid precipitate, which would have severe cellular consequences. The progression to the solid state may irreversibly affect the cell.

Low complexity domains (LCD) and neurodegenerative disease

The aggregation of alternatively-folded proteins is clearly associated with neurodegenerative disease. Mutations that lead to diseases lead to the association of low-complexity domains and aggregate formation, which is increasingly being described as phase separation. The demixed phases are stabilized by interchain backbone hydrogen bond as shown in the many beta-sheet aggregates described above. Evidence suggests that labile structures with potential for interchain H bonds and beta strand formation lead to fibril formation. The nascent interactions would involve short stretches of interchain H bonds. If so, mutations that enrich such nascent structural interaction would promote fibril formation while those that inhibit the nascent interactions would inhibit fibril formation. A study (Zhou et al, Science, 377, 2022. DOI: 10.1126/science.abn5582) verifies this.

The investigators made single amino acid variants of the low complexity domains of an RNA binding protein TDP-43 RNA that prevented that single amino acid within a region involved in interchain beta strand formation from forming a hydrogen bond through its amide hydrogen. They did this by methylating single main chain amide nitrogen, which prevents its participation in a hydrogen bond. The modification is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\): Methylation of a single backbone nitrogen in a region involved in interchain hydrogen bond and beta sheet formation in low complexity domain of proteins

Of the 23 variants they made, 9 within a continuous stretch inhibited phase separation. These 9 were at the same sites as hydrogen bonds between adjacent chains of the TDP-43 as determined by cryo-EM.

Next, they looked at other proteins with low-complexity domains that form aggregates/polymers. The proteins were the neurofilament light (NFL) chain protein, the microtubule-associated tau protein, and the heterogeneous nuclear RNPA2 (hnRNPA2) RNA-binding protein. They found 10 mutations in LCDs that were known to be associated with neurological disease. Indeed these mutations allow one extra single hydrogen bond in the low complexity domain sequences, and display enhanced aggregate formation mediated presumably through the extra interchain H bond. Specifically, the known mutations replace individual prolines, a cyclic amino acid that lacks an amide H and hence cannot donate a hydrogen bond, with another amino acid, which allows one additional hydrogen bond. Each of the known mutations was associated with neurological disease and increased stable aggregate/polymer formation. This increased aggregation/polymer (phase separation) was reversed in vitro by chemical methylation of the single amino acid change in the mutant which prevented it from forming hydrogen bonds. The site-specific methylation was performed by linking synthetic peptides containing the single, Nα-methyl amino acid to the other synthesized peptides that comprise the protein. The semisynthetic NFL protein, for example, was incubated under conditions conducive to the assembly of mature intermediate filaments.

In vitro experiments were conducted using different synthetic head domains of the neurofilament light (NFL) chain protein in which the P8 residue contained a different amino acid at those positions. The variant amino acids are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\): Variant amino acids used to at position P8 in the low complexity head domain of the neurofilament light (NFL) chain protein (after Zhou et al, ibid)

Only variants containing Leu at position P8 were able to form filaments as measured by in vitro fluorescent studies. Experiments like this are key in ascertaining where phase separation/aggregation causes and are not merely correlated with the development of complex neurodegenerative diseases.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=380&height=240)

.png?revision=1)