3.4: Analyses of Protein Structure

- Page ID

- 47023

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This section is placed in Chapter 3 before the in-depth look at protein structure in Chapter 4. It could be placed in either chapter from a learning and teaching perspective. Proteins are very complicated. This section could help students understand the tools used to explore and understand protein structure/function before a deeper dive into structural features found in Chapter 4 and throughout the book. Alternatively, it could also deepen an acquired understanding of proteins if used at the end of Chapter 4.

This comprehensive section covers topics (such as mass spectrometry, NMR, and molecular dynamics) that might not be broadly discussed or even mentioned in a one-semester survey course. Some of the methods may be more historic and less relevant today. Instructors can choose parts that are appropriate to their learning goals.

-

Conceptualize Structural Resolution in Protein Analysis:

- Explain the concept of “resolution” and how different analytical techniques (from low to high resolution) reveal various levels of protein structure and function.

-

Master Low-Resolution Analytical Techniques:

- Describe methods for determining protein concentration (e.g., UV absorbance, dye-binding assays, BCA) and discuss their advantages, limitations, and sources of interference.

- Outline techniques for amino acid composition analysis, N-/C-terminal analysis, and primary sequence determination, including the use of chemical assays and Edman degradation.

-

Understand Spectral Techniques for Structural Insights:

- Explain how circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy provides information about secondary structure by differentiating between α-helices, β-sheets, and random coils.

- Discuss the principles behind fluorescence spectroscopy, including intrinsic versus extrinsic fluorophores, fluorescence quenching, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) for studying protein-ligand interactions and conformational changes.

- Define key fluorescence concepts such as Stokes shift and anisotropy, and how they reflect changes in the protein’s environment or dynamics.

-

Grasp Mass Spectrometry for Protein Analysis:

- Describe the principles of mass spectrometry for protein characterization, including ionization techniques (ESI and MALDI), mass analyzers, and the calculation of molecular weight from m/z values.

- Differentiate between top-down, bottom-up, and middle-down approaches in proteomic analysis, and explain how peptide mass fingerprinting and tandem MS/MS contribute to protein sequencing and post-translational modification mapping.

-

Explore High-Resolution Structural Determination:

- Compare X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) in terms of sample requirements, strengths, limitations, and the type of structural information provided.

- Discuss how time-resolved crystallography and multidimensional NMR techniques offer insights into protein dynamics and conformational changes.

-

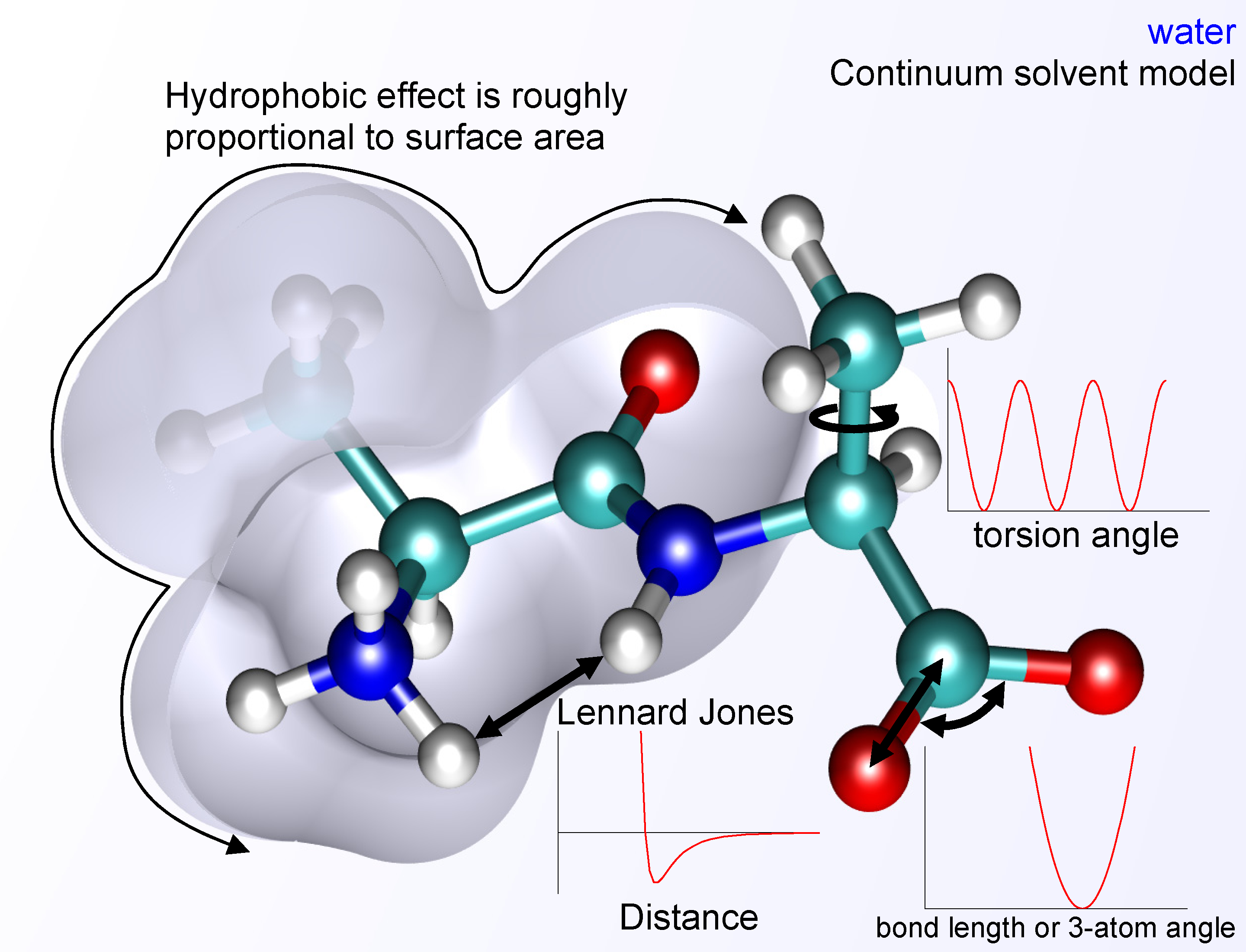

Integrate Computational and Dynamic Analyses:

- Explain the basic principles of molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, including the use of force fields to model bonded and nonbonded interactions.

- Discuss how MD simulations help predict conformational changes, calculate free energy differences (ΔG), and complement experimental data from high-resolution methods.

-

Contextualize Proteome Complexity:

- Define the proteome and discuss the challenges of proteomic analysis due to dynamic protein expression, diverse post-translational modifications, and the wide range of protein abundances.

- Describe how integrated workflows (e.g., 2D electrophoresis combined with LC-MS/MS) are used in proteomics to identify and quantify proteins in complex biological samples.

-

Synthesize Structure/Function Relationships:

- Connect the information obtained from various analytical techniques to understand how protein structure—from primary sequence to 3D architecture—dictates function.

- Evaluate how conformational dynamics, ligand binding, and post-translational modifications modulate protein activity and interactions in a cellular context.

These learning goals will enable students to critically assess experimental approaches for studying proteins and to integrate biochemical, biophysical, and computational techniques to elucidate structure/function relationships in biological macromolecules.

Introduction

In the last chapter section, we discussed how to purify a protein (primarily through differential salt precipitation and column chromatography) and how to assess its purity (primarily through various electrophoresis methods) during purification. Now, we want to continue analyzing a "pure" protein to understand its structure and the function conferred by that structure. We need a lot of information to study protein structure/function relationships. Some are "low resolution" characteristics, such as knowing the concentration of a protein. At the highest "resolution" end, we would like to know the 3D structure of a protein with a specific ligand bound to a specific site. Our goal is then to understand proteins at varying levels of complexity or "resolution," some of which are illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Various chemical and spectroscopy analysis techniques are used to achieve the specified level of structural elucidation. Spectral techniques can give us information on concentration (UV absorbance, fluorescence) and secondary structure (CD spectroscopy). Chemical analyses and mass spectroscopy give information on the amino acid composition and/or sequence. More sophisticated techniques (x-ray crystallography, cryoelectron microscopy, NMR spectroscopy) can give us 3D structural information. Each analysis shown in the figure above will be summarized below.

Sequencing the cDNA can give you some information (amino acid composition, N- and C-terminal amino acids, and the primary structure (omitted from the figure above). Even DNA sequencing won't provide information on post-translational modifications and other covalent processing (e.g., limited proteolysis, disulfide bond formation) that some of the methods below would.

In this section, we will explore some commonly used methods for protein analysis. In previous sections, we learned about the charge and chemical reactivity properties of isolated amino acids in proteins. Analyzing a whole protein is complicated because each amino acid is most often represented multiple times in the sequence. Each protein has an N-terminal and a C-terminal amino acid, as well as secondary structure. Some proteins exist biologically as multisubunit complexes, which adds to the complexity of analyses, since these proteins now have multiple N- and C-terminal ends. In addition, isolated proteins might have chemical modifications (post-translational), which add to the functionalities of the proteins and the complexities of the analyses.

Spectral techniques are widely used to provide information on protein concentration (UV absorbance, fluorescence) and secondary structure (CD spectroscopy). Chemical analyses and mass spectroscopy give information on the amino acid composition and/or sequence. More sophisticated techniques (X-ray crystallography, cryoelectron microscopy, NMR spectroscopy) can give us 3D structural information. More complete descriptions of two techniques, fluorescence spectroscopy and mass spectrometry, are presented, as their use in the analysis of biomacromolecules is underrepresented in curricula. In contrast, their use in actual laboratories becomes increasingly prevalent.

Low-Resolution Analyzes

Protein Concentration

There are multiple methods for determining protein concentrations in samples. Other components of a protein solution may interfere with the assays, so the choice of methods must be carefully determined.

1. Direct mass determination. A known, accurate amount of a dried protein is added to a solution of specific ionic strength and composition. The absorbance at a specific wavelength (usually 280 nm) is measured, and an extinction coefficient at that wavelength (ε1% = absorbance of a 1% protein solution = 1g protein/100 ml solution) is determined. If the protein's molecular weight is known from sequence analysis, a molar absorptivity can be determined. The concentration of the same protein in an unknown pure solution can then be determined. There are several problems with this technique. It requires relatively large amounts of protein to make accurate measurements. An even more difficult problem is that proteins bind water and counter-ions. Even a freeze-dried protein (frozen at -60 0C and placed in a vacuum, which causes sublimation of water and volatile salts in the solution) has probably 10% by weight of bound water (water of hydration).

2. Quantitative amino acid analysis. The protein is hydrolyzed completely to amino acids with 6N HCl. The amino acids are then separated by high-performance liquid chromatography. As amino acids elute from the column, they are reacted with a fluorescent reagent, such as ninhydrin, fluorescamine, or orthophthaldehyde (OPA), to produce a fluorescent amino acid conjugate. The fluorescence intensity of the conjugates is proportional to the concentration of the amino acids in the protein. Before hydrolysis, a known quantity of an amino acid not present in proteins (norleucine, beta-alanine) is added, and its recovery is determined at the end of the hydrolysis and fluorescence conjugation to normalize the recovery of the other amino acids. Several problems are encountered using this technique. Incomplete peptide bond hydrolysis and partial or complete destruction of serine, threonine, tryptophan, and tyrosine occur during the acid hydrolysis. The OH-containing amino acids can be determined by quantifying them at several time points during hydrolysis and extrapolating the concentrations back to zero time. Incomplete reactions with the detecting reagent can also occur.

The most widely used, and perhaps less analytically accurate, are indirect, comparative protein assays based on the chemical properties of amide bonds or the spectrophotometric properties of the side chains Trp, Tyr, and Phe. Unknown concentrations can be determined from a standard curve derived from performing the same reactions or spectrophotometric measurements on a series of solutions of known protein concentration. Below is a discussion of each of these techniques.

3. Modified Lowry protein determination. The Lowry Method is a modification of the biuret method, whose basis is described below. It is, however, much more sensitive. Biuret, as its name implies, derives from combining two urea molecules (bi-ur-et), as shown in the figure (panel A) below. A violet color results when copper sulfate is added to biuret in a concentrated hydroxide solution. An illustration of the copper (II) complex with biuret is shown in panel B of the figure. This biuret reaction also arises in any compound with three or more peptide bonds. Compare in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) the structure of Biuret and a polypeptide (Panel A).

4. Dye binding assay (Bradford method). This method is based on the binding of the dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 to proteins, resulting in a change in the dye's absorbance. The structure of the dye is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

The magnitude of the difference spectra at 595 nm is directly proportional to the protein concentration. The dye in the unbound free state has an absorbance maximum of 465 nm. Bradford initially developed the method (Analytic Biochemistry, 72, 1976), which is available commercially. The dye appears to bind to proteins through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions with a sulfonic acid group on the dye. The predominant advantage of this method is that it is cheap, simple, rapid, 3x more sensitive than the modified Lowry method, and less susceptible to interference from other compounds. The color fully develops in about 5 minutes, but decreases within 10-15 minutes when the proteins start to precipitate. Precipitation occurs more extensively at higher protein concentrations. Hence, the high-concentration standards will be affected more than the low-concentration standards.

5. Bicinchoninic Acid method (BCA). This method is based on the reduction of Cu++ to Cu+ by the peptide bond and the chelation of the Cu+ by BCA, which is monitored by absorbance at 562 nm. This method, which has been commercialized, is less prone to interference from other compounds than either the modified Lowry or the dye-binding assay. Two solutions are required: a BCA solution and a copper sulfate solution. The two are mixed to form an apple-green working solution. When protein is added, the resulting Cu+ chelates with two molecules of BCA, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): BCA analysis for protein quantitation

This results in a purple color, which can be monitored spectrophotometrically at 562 nm. An absorbance at 562 nm of 0.012 per microgram of protein added to the working reagent gives this technique high sensitivity.

6. Absorbance A280 or ratios at different wavelengths. This method is based on the fact that the three aromatic acids (Tyr, Phe, Trp) have significant absorbances in the UV. The absorption spectra of the three amino acids as a function of wavelength are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Note the log scale on the y-axis.

The elution of proteins from chromatography columns is typically monitored by measuring the absorbance of the eluate at 280 nm as it leaves the column, a proxy for protein concentration. An average protein at a concentration of 1 mg/ml has an A280 of about 1. However, only two amino acids absorb significantly at this wavelength. Since proteins have variable numbers of these amino acids, this measurement can only estimate the concentration of an unknown protein.

The Beer-Lambert law shows that the absorbance of a chromophore in solution is given by

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{A}=\epsilon \mathrm{l} \mathrm{c}

\end{equation}

where A is the absorbance at a given wavelength, ε is the molar absorptivity, l is the path length of the cuvette, and c is the concentration (mol/L). Pace et al. have shown that, based on over a hundred measurements on 61 proteins in an aqueous solution, the ε(280), the molar absorptivity at 280 nm, is given by this empirical equation:

\begin{equation}

\epsilon(280)\left(\mathrm{M}^{-1} \mathrm{~cm}^{-1}\right)=(\# \operatorname{Trp})(5,500)+(\# \mathrm{Tyr})(1,490)+(\# \text { cystine })(125)

\end{equation}

Proteins also absorb strongly at wavelengths less than 240 nm. This part of the absorption spectra arises from the above-mentioned amino acids and contributions from His, Met, Cys, and the peptide bond. At these wavelengths, the absorbance is less dependent on the protein's amino acid composition, but it becomes increasingly susceptible to interference from other substances. Contaminating nucleic acids, which absorb maximally at 260 nm, also contribute to the absorbance at 280 nm. Hence, the A280/A260 ratio can be determined, and the contribution of nucleic acids can be removed through appropriate calculations. Optimal reliability is achieved by measuring A280/A205 values since, at 205 nm, a large fraction of the absorbance due to the peptide bond. pH changes have little effect on the absorbance of the peptide bond but have a much larger effect on Tyr. At high pH, the side-chain hydroxyl is deprotonated (pKa = 10.5), with concomitant changes in A295. These changes can be used to follow the titration of the Tyr residues in a protein.

Molecular Weight

Hydrodynamic techniques can estimate molecular weights, including size exclusion chromatography (under denaturing conditions using standards of known molecular weight), ultracentrifugation, and dynamic light scattering. In addition, they can be determined by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, again under denaturing conditions using standards. More precisely, it could be determined through protein or cDNA sequence analyses. As described below, mass spectrometry is the most accurate method for smaller proteins.

Specific Amino Acids

Aromatic amino acids can be detected by their characteristic absorbance profiles. As shown in Chapter 3.1: Amino Acids and Peptides, amino acids with specific functional groups can be determined by chemical reactions with specific modifying groups.

Amino Acid Composition

At low resolution, we can determine the amino acid composition of the protein by hydrolyzing it in 6 N HCl at 100 °C under vacuum for various time intervals. After removing the HCl, the hydrolysate is applied to an ion-exchange or hydrophobic-interaction column, and the amino acids are eluted and quantified using known standards. A non-naturally occurring amino acid, like norleucine, is added in known amounts as an internal standard to monitor quantitative recovery during the reactions. The separated amino acids are often derivatized with ninhydrin or phenylisothiocyanate to facilitate their detection. The reaction is carried out for 24, 36, and 48 hours since amino acids with OH (like ser) are destroyed. A time course allows the concentration of Ser at time t=0 to be extrapolated. Trp is also destroyed during the process. In addition, the amide links in the side chains of Gln and Asn are hydrolyzed to form Glu and Asp, respectively.

N- and C-Terminal Amino Acid Analysis

The amino acid composition does not determine the protein's sequence. The N-terminus of the protein can be determined by reacting the protein with fluorodinitrobenzene (FDNB) or dansyl chloride, which reacts with any free amine in the protein, including the epsilon amino group of lysine. The amino group of the protein is linked to the aromatic ring of the dinitrobenzene through an amine and to the dansyl group by a sulfonamide and is hence stable to hydrolysis. The protein is hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl, and the amino acids are separated by TLC or HPLC. Two spots should result if the protein were a single chain with some Lys residues. The labeled amino acid other than Lys is the N-terminal amino acid. The C-terminal amino acid can be determined by adding carboxypeptidases, which cleave amino acids from the C-terminal. A time course must be performed to determine which amino acid is released first. N-terminal analysis can also be done as part of sequencing the entire protein using Edman degradation.

Primary Sequence

Protein Sequencing using Edman Degradation

Edman degradation, developed by Pehr Edman, is a method of sequencing amino acids in a peptide. In this method, the amino-terminal residue is labeled and cleaved from the peptide without disrupting the peptide bonds between other amino acid residues. The reaction is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Phenyl isothiocyanate is reacted with an uncharged N-terminal amino group under mildly alkaline conditions to form a cyclical phenylthiocarbamoyl derivative. Under acidic conditions, this terminal amino acid derivative is cleaved to a thiazolinone. The thiazolinone amino acid is then selectively extracted into an organic solvent and treated with acid to form the more stable phenylthiohydantoin (PTH)- amino acid derivative that can be identified by using chromatography or electrophoresis. This procedure can then be repeated to identify the next amino acid.

A major drawback of Edman degradation is that the peptides sequenced in this manner cannot exceed 50-60 residues (and, in practice, are typically under 30). The peptide length is limited because cyclical derivatization does not always go to completion. The derivatization problem can be resolved by cleaving large peptides into smaller peptides before proceeding with the reaction. It can accurately sequence up to 30 amino acids, and modern instruments can achieve over 99% efficiency per amino acid. An advantage of the Edman degradation is that it requires only 10-100 picomoles of peptide for sequencing. The Edman degradation reaction was automated in 1967 by Edman and Beggs to speed up the process, and 100 automated devices were in use worldwide by 1973.

Because the Edman degradation proceeds from the N-terminus of the protein, it will not work if the N-terminus has been chemically modified (e.g., by acetylation or formation of pyroglutamic acid). Sequencing will stop if a non-α-amino acid is encountered (e.g., isoaspartic acid), since the favored five-membered ring intermediate cannot be formed. Edman degradation is generally not useful in determining the positions of disulfide bridges. It also requires peptide amounts of 1 picomole or above for discernible results.

Secondary Structure

The percent and type of secondary structure can be determined using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. In this method, right- and left-circularly polarized light illuminates a protein, which is chiral because it is composed entirely of L-amino acids. (The mirror image would be a protein of the same sequence made of D-amino acids.) Differential absorption of the right and left forms gives a CD spectrum

Circularly polarized light can be made when plane-polarized light of the same amplitude and wavelength meets out of phase by 900. (If they were out of phase by 1800, they would cancel.)

- To see an animation of how circularly polarized light can be created, go to this page and select: 1. Superposition of plane-polarized waves 2.

If R and L circularly polarized light of the same wavelength and amplitude are passed through an optically inactive medium, the two waves combine (vectorially) to produce plane-polarized light.

- To see an animation of how circularly polarized light can be created, go to this page and select 1. Superposition of circularly polarized waves

Optical activity is observed only when the environment in which a transition occurs is asymmetric.

The peptide (amide) bond absorbs UV light in the range of 180 to 230 nm (far-UV range), so this region of the spectra gives information about the protein backbone and, more specifically, the secondary structure of the protein. The main electronic energy transitions are n → π* at 220 nm and π → π * at 190 nm for the peptide bond. There is a contribution from aromatic amino acid side chains, but it is small, given the large number of peptide bonds. The lone pair on the nitrogen adjacent to the pi bond can be considered rehybridized from sp3 to sp2, allowing for conjugation of the p electrons (which lowers the energy of the electrons). The Hückel diagram shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) below shows three molecular (not atomic) orbitals generated from the three atomic p orbitals.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Hückel molecular orbitals for the peptide bond

The middle one (with one node) has energy similar to the separate atomic p orbitals and is considered a nonbonding molecular orbital. This is consistent with the lone nonbonding pair on the nitrogen atom.

The peptide bonds in a protein's asymmetric environment will absorb light in this wavelength range (promoting electrons to higher energy levels). In different secondary structures, the peptide bond electrons absorb right- and left-circularly polarized light differently (for example, they exhibit different molar absorptivities). Hence, α, β, and random coil structures exhibit distinguishable far-UV CD spectra.

To see an animation of circularly polarized light, go to this page and select 1. Circularly Polarized Waves

Stated in another way, if plane-polarized light, which is a superposition of right and left circularly polarized light, passes through an asymmetric sample, which absorbs right and left circularly polarized light differently (i.e, they display circular dichroism), then the light passing through the sample after vector addition of the right and left circularly polarized light gives elliptically polarized light.

To see an animation of elliptically polarized light, go to this page and select 2. Plane-polarized waves in a medium with circular dichroism

If the chiral molecules also have a different index of refraction for R and L circularly polarized light, an added effect is the rotation of the angle of the elliptically polarized light. The far-UV CD spectrum of the protein is sensitive to its main chain conformation. The CD spectra of alpha and beta secondary structures are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).

Protein side chains also find themselves in such an asymmetric environment. If irradiated with circularly polarized UV light in the range of 250-300 nm (near UV), differential absorption of right and left circularly polarized light by the aromatic amino acids (Tyr, Phe, Trp) and disulfide bonds occurs, and a near UV CD spectra result. Suppose a protein's near-UV CD spectra are taken under two different sets of conditions, and the spectra differ. In that case, it can be inferred that the environment of the side chains differs, and hence the proteins have somewhat different conformations. It will not provide information about the backbone's secondary structure, as it requires lower wavelengths for absorption. Instead, it can show differences in tertiary structure.

Analysis of Proteins Using Fluorescence Spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectroscopy is widely used to study many aspects of protein chemistry. Although this technique is not often used in lower-level undergraduate classes, it has become so important in the study of biomolecules that a detailed explanation is necessary.

When molecules absorb energy, electrons are promoted to higher electronic energy states. This is the basis of absorption spectroscopy. These excited-state electrons can return to the ground state in processes that don't emit photons of light (ie, nonradiative processes) or radiative processes that emit light. In simple absorption spectroscopy, excited-state electrons relax to the ground state through collisions. In radiative deexcitation, light is emitted. This process of light emission is called luminescence, which can be divided into two categories:

- fluorescence: If one electron from a ground state electron pair is excited to a higher energy state, the excited electrons can still be spin paired with their ground state counterpart - i.e., they have opposite spins. The excited electron can return to the ground state without reversing its spin. (The excited state is a singlet state with S, the total spin state, given the formula S = 2s +1, where s = 0 (sum of +1/2 and -1/2) and S = 1 for a singlet.) This process, which results in rapid photon emission, is "spin allowed." The photon emission rate is about 108 s-1, resulting in a lifetime (the average time between excitation and emission) of the excited state of about 10 ns.

- phosphorescence: If, in contrast to the above case, the spin of the excited electron is flipped, then its transition back to the ground state is "spin forbidden" since the excited state electron and its ground state counterpart have the same spin state. (The excited state is a triplet state with S, the total spin state, given by the formula S = 2s +1, where s = 1 (1/2 + 1/2) and S = 3 for a triplet. Hence, this transition occurs slowly (in the ms-s range). Toys that glow in the dark display even longer phosphorescence lifetimes. (Note: This guide will concentrate on fluorescence.)

Competing with the two deexcitation processes are nonradiative processes (such as through collisions). Given these competing processes, it might be expected that phosphorescence in liquid solutions at room temperature might not be detectable.

Molecules that fluoresce are typically aromatic, which absorb readily in the UV and visible light regions. Common fluorophores are quinine, found in tonic water (observe the faint blue glow at the surface when placed in direct sunlight), and fluorescein and rhodamine, two fluorophores often added to antifreeze. Atoms are usually nonfluorescent, except europium and terbium ions from the lanthanide series. These fluoresce when electronic transitions occur between f orbitals, which are shielded from solvent relaxation by the filled 5s and 5p orbitals.

Among biological molecules, some, especially macromolecules with aromatic groups, fluoresce. These groups are called intrinsic fluorophores and, in proteins, include the side chains of the aromatic amino acids tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine. The indole side chain of tryptophan is the most fluorescent, and its emission spectrum, which is sensitive to solvent conditions, is often blue-shifted when the ring is buried and red-shifted when solvent-exposed. Nucleic acids, although they also contain aromatic bases, are poor fluorophores. Many biological molecules can be made fluorescent by covalently modifying them (via nucleophilic groups on the biological molecule) with exogenously added fluorophores, such as fluorescein isothiocyanate, rhodamine isothiocyanate, or dansyl chloride. These are called extrinsic fluorophores. These include molecules that bind noncovalently to structures such as ds-DNA (ethidium bromide) or lipid membranes (diphenylhexatriene). Some biological fluorophores are substrates for enzyme reactions. Examples include oxidized flavins (FAD, FMN) and the reduced form of NAD (i.e., NADH). Another type of useful fluorophore is an indicator, whose fluorescent properties change with a parameter such as pH or [Ca2+].

The electronic transitions that occur during fluorescence can be represented by a Jablonski diagram as shown in the two-part Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) (A and B) below.

In panel A, the ground and first excited electronic states are shown. Each electronic state has multiple vibrational energy levels 0, 1, 2, ... and 0', 1', 2', ... This simple diagram ignores quenching of fluorescence, resonance energy transfer, etc. The transitions, represented by vertical lines, are considered to be instantaneous. They take about 10-15 s, so the nuclei don't move during that time. The ground-state electron is considered in the zero vibrational level, so thermal energy is insufficient to promote it to the next vibrational level. When light is absorbed, the electron is promoted to a higher vibrational level within a higher electronic level. Usually, the excited electrons relax quickly (< 1 ps) to the lowest vibrational level of S1 or S2 through internal conversion. Fluorescence emission may occur from the lowest vibrational state of S1 to any of the vibrational states of So. Hence, the photon emitted is lower in energy (longer in wavelength) than the absorbed photon. Also, since both processes involve the movement of an electron to different vibrational levels, with absorption or emission of a photon, and nonradiative vibrational relaxation within those levels, the emission spectra are often the mirror image of the absorption spectra. (This assumes that the vibrational levels in So and S1 are similarly spaced. Alternatively, electrons in S1 may flip their spin and convert to the T1 state via intersystem crossing, leading to phosphorescence.

Panel B above shows blue lines for individual absorbances and red lines for emissions. Note that the excitation from 0 to 8' has the highest energy of absorption (lowest wavelength) but gives little intensity as it would occur with low frequency. If you were to draw a line over the tops of the lines in panel B, you would get simple excitation and emission spectra, which would be mirror images of each other. The emission peak is at a longer wavelength since energy was lost on vibrational, nonradiative relaxation of the excited electron. The difference in peak excitation and emission wavelengths is called the Stokes Shift. This shift is greatest for fluorophores in polar environments. Inferences can be made considering the disposition of a side chain (buried or surface) if changes in fluorescence properties (intensity, Stokes' shift) are noted on protein denaturation. Also, many probes are weakly fluorescent in aqueous solution but fluoresce intensely in nonpolar media (e.g., bound to a hydrophobic pocket in a protein, bilayer, or lipoprotein).

Emission spectra are usually independent of excitation wavelength (Kasha's rule). This occurs because the excited state rapidly relaxes into the lowest vibrational energy level. There are also exceptions to the mirror image rule. Deviations arise from a change in the geometry of nuclei in the excited state of the molecule. This may occur if the lifetime of the S1 state is long, allowing time for motion before emission.

An example is p-terphenyl in cyclohexane, where the rings become more coplanar in the excited state. Since there is an electron shift in the excited state, a complex between the excited fluorophore and another solution component may arise (charge-transfer complex). Alternatively, some fluorophores form dimers (e.g., pyrene) at higher concentrations. At high concentrations, changes in the emission spectra occur, arising from excited-state dimers or excimers. Acridine shows two emission spectra at different pHs, arising from changes in the pKa on excitation (5.45 to 10.7). Finally, exciting a fluorophore at different wavelengths (EX 1, EX 2, EX 3) does not change the emission profile. Still, it does produce variations in fluorescence emission intensity (EM 1, EM 2, EM 3) that correspond to the amplitude of the excitation spectrum.

Fluorophores can chemically modify nucleophilic side chains such as lysines and cysteines. Changes in intrinsic fluorescence in proteins can be used to measure ligand binding, conformational changes in the protein during binding interactions, changes in solution conditions, and protein denaturation. Let's explore a few fluorescence methods widely used to explore protein structure and function.

Fluorescence Quenching

Some chemical species (for example, iodide and monomeric, unpolymerized acrylamide), when added to a protein solution, can decrease the fluorescence of an intrinsic, surface-accessible fluorophore, such as the tryptophan side chain, providing information on the local environment of the intrinsic fluorophore (for example, tryptophan side-chain accessibility). For example, a buried tryptophan or probe will show little change in fluorescence intensity in the presence of a large, polar quencher. In contrast, a surface tryptophan or probe will show a significant decrease in fluorescent intensity. It is somewhat amazing that O2, when added to a solution under increasing pressure, can quench the fluorescence of even buried tryptophan side chains, implying minimal diffusional barriers to O2 access. This suggests significant conformational flexibility of the protein.

Quenching can be dynamic, occurring when the quencher collides with the intrinsic fluorophore, or static, when the quencher binds to a site near the fluorophore as a prelude to quenching.

Collisional quenching is described by the Stern-Volmer equation.

\begin{equation}

\frac{F_{0}}{F}=1+k_{q} \tau_{0}[Q]=1+K_{D}[Q]

\end{equation}

where Fo and F are the fluorescent intensities in the absence and presence of the quencher, kq is the biomolecular quenching constant, τo is the lifetime of the fluorophore in the absence of the quencher, and [Q] is the concentration of the quencher. kqτo = KD is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant.

A plot of Fo/F vs [Q] is linear, with a slope of KD. 1/KD is the quencher concentration at which Fo/F = 2, or 50% of the fluorescence intensity, is quenched. A linear plot indicates a single class of fluorophores, all of which are equally accessible to the quencher. A nonlinear plot would be found for the quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in proteins by charged or polar quenchers for proteins with more than one tryptophan, and in which some are buried. Static quenching also results in a linear SV plot. Different dependencies on temperature and viscosity can distinguish dynamic and static quenching. Since dynamic quenching depends on diffusion, higher temperatures result in higher diffusion coefficients; therefore, kq should increase with temperature. If static quenching is involved, higher temperatures will probably reduce complex formation.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

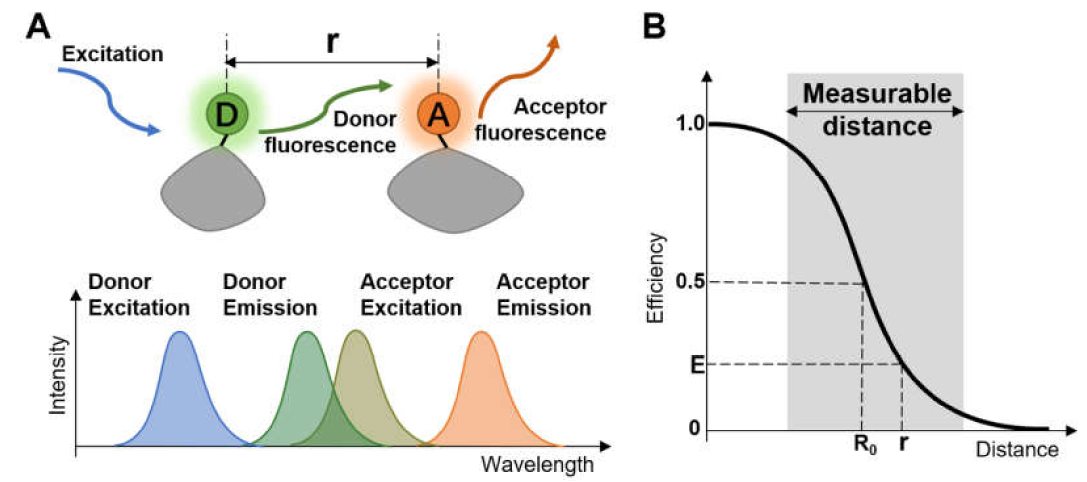

If an absorbing species is near an excited-state fluorophore, and if the emission spectrum of the fluorophore overlaps the absorption spectrum of the second species, coupling of the two dipoles can occur, and energy can be transferred from the excited state of the fluorophore (donor D) to the second absorbing species (acceptor A). This energy transfer occurs through dipole coupling, not through the trivial emission and absorption of a photon. No photon is produced. This process is called fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). Efficiency, E, of FRET for a single donor/acceptor pair at a fixed distance is given by:

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{E}=\frac{\mathrm{R}_{0}^{6}}{\left(\mathrm{R}_{0}^{6}+\mathrm{r}^{6}\right)}=\frac{1}{1+\left(\frac{\mathrm{r}}{\mathrm{R}_{0}}\right)^{6}}

\end{equation}

Ro is the Förster distance (or radius) with a 50% transfer efficiency, and r is the distance between the donor and acceptor. Ro measures the spectral overlap of the donor and acceptor (for which most biological macromolecules have a value of 30-60 angstroms). This equation shows that efficiency depends on 1/r^6, making FRET exquisitely sensitive to distance. Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) below illustrates FRET and its distance dependency.

Anisotropy or polarization

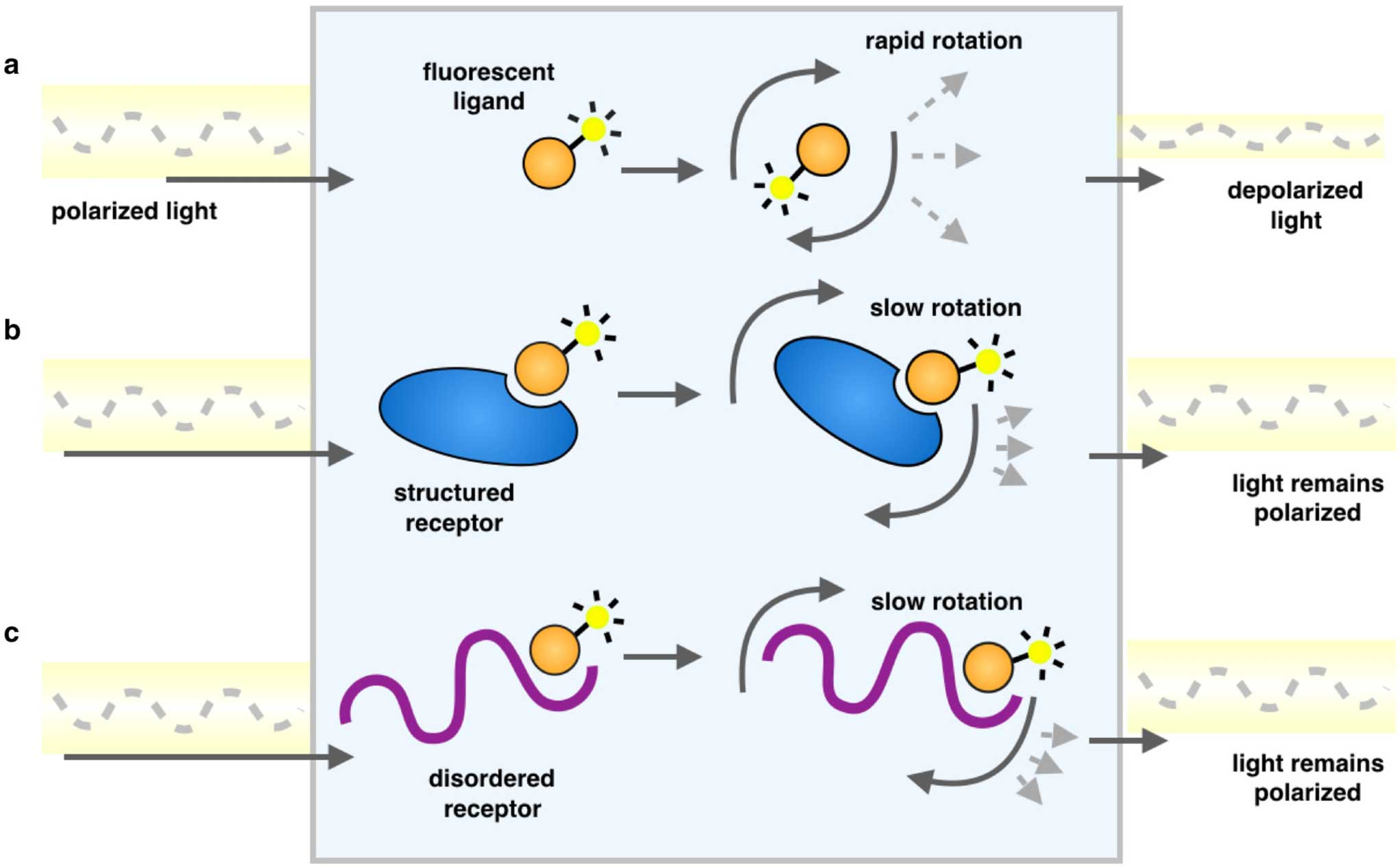

These measure the extent of rotation of the fluorophore during its fluorescent lifetime. If a small fluorophore binds to a large molecule, its rotational diffusion constant decreases, and its anisotropy increases, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\).

Schematic representation of a fluorescence polarization experiment. As a result of the rapid tumbling of molecules in solution, when a fluorescently labeled ligand is excited with plane-polarized light, the resulting emitted light is largely depolarized (a). Upon binding another species, a larger proportion of the emitted light remains in the same plane as the excitation energy because the rotation is slowed as the effective molecular size increases, whether it is an ordered molecular structure (b) or one that is disordered (c)". Since viscosity decreases rotational diffusion rates, changes in fluorescence (such as inside a bilayer) can be inferred from these measurements. For example, membranes more enriched in saturated fatty acids should show increased anisotropy of a hydrophobic, fluorescent probe compared to the same probe in a bilayer enriched in polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Analysis of Protein Using Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry supplants traditional methods (see above) to determine a protein's molecular mass and structure. Its power comes from its exquisite sensitivity and modern computational methods for determining structure by comparing ion fragment data with databases of known protein structures. In mass spectrometry, a molecule is first ionized in an ion source. An electric field then accelerates the charged particles into a mass analyzer, where they are subjected to an external magnetic field. The external magnetic field interacts with the magnetic field generated by the charged particles' motion, deflecting them. The deflection is proportional to the mass-to-charge ratio, m/z. Ions then enter the detector, which is usually a photomultiplier. Sample introduction into the ion source occurs through simple diffusion of gases and volatile liquids from a reservoir, by injecting a liquid sample containing the analyte via a fine mist, or, for very large proteins, by desorbing a protein from a matrix using a laser. Complex mixtures are analyzed by coupling HPLC to mass spectrometry in an LC-MS system.

There are many methods for ionizing molecules, including atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), chemical ionization (CI), and electron impact (EI). The most common methods for protein/peptide analyses are electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI).

Electrospray ionization (ESI)

The analyte, dissolved in a volatile solvent such as methanol or acetonitrile, is injected into the ion source through a fine stainless steel capillary at a low flow rate. A high voltage (3-4 kV) is applied to the capillary, giving it a positive charge relative to the oppositely charged electrode. The flowing liquid becomes charged with the same polarity as the polarity of the positively charged capillary. The high field leads to the emergence of the sample as a charged aerosol spray of charged microdrops, thereby reducing electrostatic repulsions within the liquid. This method uses electrical energy to produce the aerosol, rather than mechanical energy to produce a liquid aerosol, as in a perfume atomizer. Surrounding the capillary is a flowing gas (nitrogen) that helps move the aerosol toward the mass analyzer. As the volatile solvent evaporates, the microdrops become smaller, increasing the positive charge density on them. Eventually, electrostatic repulsions cause the drops to explode in a series of steps, ultimately producing the analyte devoid of solvent. This gentle ionization method produces analytes that are not cleaved but ready for introduction into the mass analyzer.

Proteins emerge from this process with a roughly Gaussian distribution of positive charges on basic side chains. You studied mass spectra of small molecules induced by electron bombardment in organic chemistry. This produces ions with a +1 charge as an electron is stripped from the neutral molecule. The highest m/z peak in the spectrum corresponds to the parent ion, M+. The highest m/z ratio detectable in the mass spectrum is in the thousands. However, large peptides and proteins with high molecular mass can be detected and resolved because their ions carry a charge greater than +1. In 2002, John Fenn was awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing and using ESI to study biological molecules.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) shows an example of an ESI spectrum of apo-myoglobin.

Note the roughly Gaussian distribution of the peaks, each representing the intact protein with charges differing by +1. Proteins acquire positive charges by protonating amino acid side chains and by charges induced during electrospray. Based on the amino acid sequence of myoglobin and the assumption that the pKas of the side chains are the same in the protein as for isolated amino acids, the calculated average net charges of apomyoglobin (apoMb) would be approximately +30 at pH 3.5, +20 at pH 4.5, +9 at pH 6, and 0 at pH 7.8 (the calculated pI). The mass spectrum below was obtained by direct injection of apoMb into the MS in 0.1% formic acid (pH 2.8)—charges on the peptide result from those present before the electrospray and those induced during the process.

The protein's molecular mass can be determined by analyzing two adjacent peaks, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\).

Suppose M is the molecular mass of the analyte protein, and n is the number of positive charges on the protein represented in a given m/z peak. In that case, the following equations give the molecular mass M of the protein for each peak:

\begin{equation}

\begin{gathered}

\mathrm{M}_{\text {peak } 2}=\mathrm{n}(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\text {peak } 2}-\mathrm{n}(1.008) \\

\mathrm{M}_{\text {peak } 1}=(\mathrm{n}+1)(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\text {peak } 1}-(\mathrm{n}+1)(1.008)

\end{gathered}

\end{equation}

where 1.008 is the atomic weight of H. Since there is only one value of M, the two equations can be set equal to each other, giving:

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{n}(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\text {peak } 2}-\mathrm{n}(1.008)=(\mathrm{n}+1)(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\text {peak } 1}-(\mathrm{n}+1)(1.008)

\end{equation}

Solving for n gives:

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{n}=\frac{(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\mathrm{peak} 1}-(1.008)}{(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\mathrm{peak} 2}-(\mathrm{m} / \mathrm{z})_{\mathrm{peak} 1}}

\end{equation}

Knowing n, the molecular mass M of the protein can be calculated for each m/z peak. The best value of M can then be determined by averaging the M values determined from each peak (16,956 from the above figure). For peaks from m/z of 893-1542, the calculated values of n ranged from +18 to +10.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)

This technique for larger biomolecules (proteins and polysaccharides) involves mixing the analyte with an absorbing matrix. Laser excitation of the matrix leads to energy transfer, resulting in ionization and the "launching" of the matrix and analyte in ion form from the solid mixture. Parent ion peaks of (M+H)+ and (M-H)- are formed.

The Mass Analyzer separates the created ions based on m/z ratios. Let's consider two: the quadrupole ion trap and the time-of-flight. There are several general types of mass analyzers, including magnetic sector, time-of-flight, quadrupole, and ion trap.

Quadrupole ion trap (used in ESI) - A complex mixture of ions can be contained (or trapped) in this mass analyzer. Two common types are linear and 3D quadrupole. If a dipole has two poles (+ and -) separated by some distance, then a quadrupole has four poles (+, -, +, and -) arranged geometrically such that each + has a - on each side and vice versa. Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) below shows linear and 3D quadrupoles.

As dipoles display positive and negative charge separation on a linear axis, quadrupoles have either opposite electrical charges or opposite magnetic fields at the opposing ends of a square or cube. In charge separation, the monopole (sum of the charges) and dipoles cancel to zero, but the quadrupole moment does not. The quadrupole traps ions using a combination of fixed and alternating electric fields. The trap contains helium at 1 mTorr. For the 3D trap, the ring electrode has an oscillating RF voltage, which keeps the ions trapped. The end caps also have an AC voltage. Ions oscillate in the trap at a "secular" frequency determined by the RF voltage frequency and, of course, the m/z ratio. By increasing the amplitude of the RF field, the ion motion in the trap becomes destabilized, leading to ion ejection into the detector. When the secular frequency of ion motion matches the applied AC voltage across the end cap electrodes, resonance occurs, increasing the ions' motion amplitude and allowing leakage out of the ion trap into the detector.

Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS): Quadrupole mass analyzers, which can select ions of varying m/z ratios in the ion traps, are commonly used in tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). In this technique, the selected ions are further fragmented into smaller ions by collision-induced dissociation (CID). When performed on all of the initial ions present in the ion trap, the sequence of a peptide/protein can be determined. This technique usually requires two mass analyzers with a collision cell in between, where selected ions are fragmented by collision with an inert gas. Using a quadrupole ion trap, it can also be done in a single mass analyzer.

In time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometry (used in MALDI), a long tube determines the time required for ion detection. The small molecular mass ions reach the detector the fastest.

Sequence Determination Using Mass Spectrometry

In a typical MS/MS experiment to determine a protein sequence, a protein is cleaved into protein fragments using an enzyme such as trypsin, which cleaves on the carboxyl side of Lys and Arg residues. The average protein size in the human proteome is approximately 50,000. If the average molecular mass of an amino acid in a protein is around 110 (18 subtracted since water is released on amide bond formation), the average number of amino acids in the protein would be around 454. If 10% of the amino acids are Arg and Lys, then on average, there would be approximately 50 Lys and Arg, and hence 50 tryptic peptides of average molecular mass 1000. The fragments are introduced in the MS, where a peptide fragment fingerprint analysis can be performed. The molecular weights of the fragments can be determined and compared with those of known peptide digestion products from known proteins to identify the analyte protein.

Ions with the original N terminus are denoted as a, b, and c, while ions with the original C terminus are denoted as x, y, and z. c and y ions gain an extra proton from the peptide to form positively charged -NH3+ groups. Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) below shows peaks for a 4-amino acid peptide fragmentation pattern

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): 4-amino acid peptide fragmentation peaks. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/F...gmentation.gif. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Ions with the original N terminus are denoted as a, b, and c, while ions with the original C terminus are denoted as x, y, and z. c and y ions gain an extra proton from the peptide to form positively charged -NH3+ groups. The ions observed depend on many factors, including the peptide sequence, its original charge, the collision energy used to induce fragmentation, etc. Low energy fragmentation of peptides in ion traps usually produces a, b, and y ions, along with peaks resulting from loss of NH3 (a*, b*, and y*) or H2O (ao, bo, and yo). No peaks resulting from the fragmentation of side chains are observed. Fragmentation at two sites in the peptide (usually at the b and y sites in the backbone) forms an internal fragment.

The y1 peak represents the tryptic peptide's C-terminal Lys or Arg (in this example). Peak y2 has one more amino acid than y1, and the molecular mass difference identifies the extra amino acid. Peak y3 is likewise one amino acid larger than y2. All three y fragment peaks have a common Lys/Arg C-terminal, and the charged fragment contains the C-terminal end of the original peptide. All b fragment peaks for a given peptide contain a common N-terminal amino acid, with b1 the smallest. Note that the subscript represents the number of amino acids in the fragment. By identifying b and y peaks, the actual sequence of small peptides can be determined. Usually, spectra are matched to databases to identify the structure of each peptide and, ultimately, that of the protein. The actual m values for fragments can be calculated as follows, where (N is the molecular mass of the neutral N terminal group, (C) is the molecular mass of the neutral c terminal group, and (M) is the molecule mass of the neutral amino acids. (For N-terminal amino acid, add 1 H. For C terminus, add OH.)

- a: (N)+(M)-CHO

- b: (N)+(M)

- y: (C)+(M)+H (note in the figure above that the amino terminus of the y peptides has an extra proton in the +1 charged peptides.)

m/z values can be calculated from the m values by adding the mass of the extra proton to the overall z, if the overall charge is +1, etc.

For example, from these MW values, the human Glu1- fibrinopeptide B sequence can be determined from MS/MS spectra shown in an annotated form in Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\). Note that most of the b peaks are b*, resulting from the loss of NH3 from the N terminus.

Now, let's step back and get a broader picture of structure analysis by mass spectrometry. In general, proteins are analyzed either in a "top-down" approach, in which they are analyzed intact, or in a "bottom-up" approach, in which they are first digested into fragments. An intermediate "middle-down" approach, in which larger peptide fragments are analyzed, may also be used. However, the top-down approach is mostly limited to low-throughput single-protein studies due to issues in handling whole proteins, their heterogeneity, and the complexity of their analyses.

In the second approach, referred to as the "bottom-up" MS, proteins are enzymatically digested into smaller peptides using a protease such as trypsin, which cleaves peptide chains mainly at the carboxyl side of lysine or arginine, except when either is followed by proline. It is used for numerous biotechnological processes. The process is commonly referred to as trypsin proteolysis or trypsinization, and proteins that have been digested/treated with trypsin are said to have been trypsinized.

Subsequently, these peptides are introduced into the mass spectrometer and identified by peptide mass fingerprinting or tandem mass spectrometry. Hence, this approach uses peptide-level identification to infer the presence of proteins pieced back together via de novo repeat detection. The smaller and more uniform fragments are easier to analyze than intact proteins and can be also determined with high accuracy, this "bottom-up" approach is therefore the preferred method of studies in proteomic studies. A further approach that is beginning to be useful is the intermediate "middle-down" approach, in which proteolytic peptides larger than the typical tryptic peptides are analyzed.

Proteins of interest are usually part of a complex mixture of multiple proteins and molecules, which coexist in the biological medium. This presents two significant problems. First, the two ionization techniques used for large molecules are effective only when the mixture contains roughly equal amounts of the constituents. At the same time, different proteins tend to be present in widely differing amounts in biological samples. If such a mixture is ionized using electrospray or MALDI, the more abundant species tend to "drown" or suppress signals from less abundant ones. Second, the mass spectrum from a complex mixture is very difficult to interpret due to the overwhelming number of mixture components. This is exacerbated by the fact that a protein's enzymatic digestion yields multiple peptide products.

In light of these problems, methods such as one- and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and high-performance liquid chromatography are widely used to separate proteins. The first method fractionates whole proteins via two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Figure 3.31). The first dimension of 2D gel electrophoresis is isoelectric focusing (IEF). In this dimension, the protein is separated by its isoelectric point (pI), and the second dimension is SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). This dimension separates proteins based on their molecular weight. Once this step is complete, in-gel digestion proceeds.

In some situations, combining both of these techniques may be necessary. Gel spots identified on a 2D Gel are usually attributable to one protein. If protein identity is desired, the in-gel digestion method is usually used, in which the protein spot of interest is excised and proteolytically digested. The peptide masses resulting from the digestion can be determined by mass spectrometry using peptide mass fingerprinting. If this information does not allow unequivocal protein identification, its peptides can be subject to tandem mass spectrometry for de novo sequencing. Small changes in mass and charge can be detected with 2D-PAGE. The disadvantages of this technique are its small dynamic range compared to other methods. Some proteins are still difficult to separate due to their acidity, basicity, hydrophobicity, and size (too large or too small).

The second method, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC/MS), is used to fractionate peptides after enzymatic digestion. Characterization of protein mixtures using HPLC/MS is also called shotgun proteomics and MuDPIT (Multi-Dimensional Protein Identification Technology). One or two steps of liquid chromatography fractionate a peptide mixture that results from the digestion of a protein mixture. The chromatographic eluant can be directly introduced into the mass spectrometer via electrospray ionization or deposited onto a series of small spots for later MALDI mass analysis.

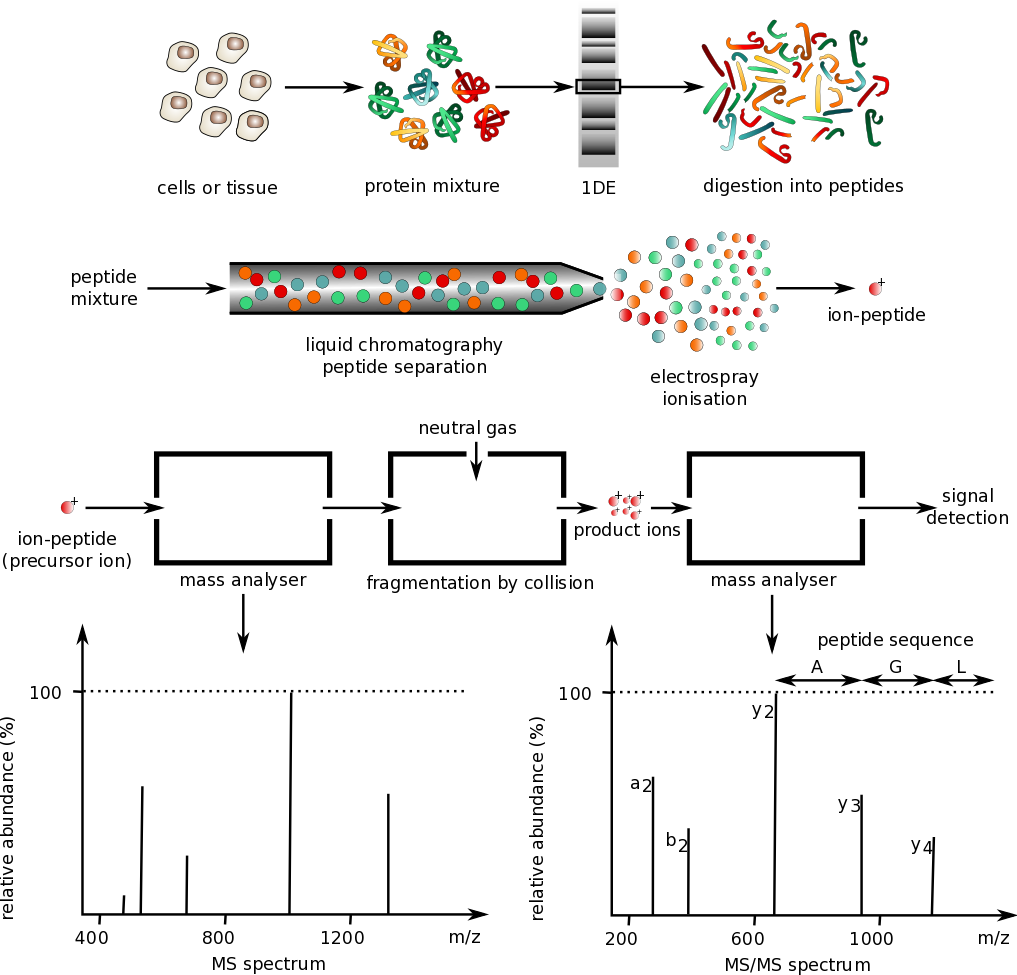

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) shows the general schema for analyzing proteins by mass spectrometry.

Protein mixtures are prepared from cell culture or tissue samples and separated by gel electrophoresis. Single proteins are isolated and digested using trypsin to produce a peptide mixture. Peptides are separated by liquid chromatography and analyzed by mass spectrometry

3D Structural Determination

The 3D structure of a protein can be determined in four main ways: X-ray crystallography, multidimensional NMR, cryoelectron microscopy, and computer modeling using artificial intelligence and machine learning.

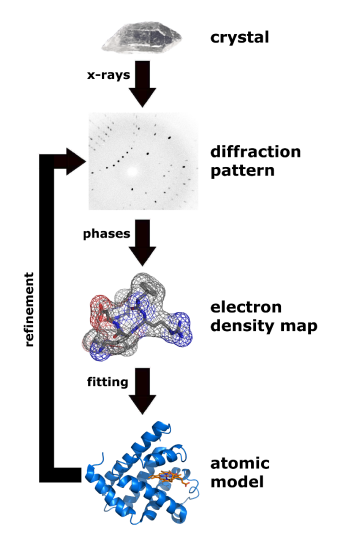

X-Ray Crystallography

In this technique, proteins are induced to form solid crystals in which the individual molecules pack in a well-defined crystal lattice. X-rays are aimed at the crystals. The X-rays are scattered off the crystal and collected by a detector. The scattered X-rays undergo constructive and destructive interference (as water waves do), forming a diffraction pattern. The crystal's spacing and types of atoms determine the diffraction pattern. Hence, from a given 3D structure, a specific diffraction pattern is formed. Using sophisticated mathematics (Fourier Transformations), the diffraction pattern can be converted back into the 3D structure of the object —in this case, the protein's atoms.

Constructive and destructive interference and the formation of a "diffraction" pattern can be readily visualized in two PHET simulations. Follow the instructions below.

Simulation 1: Slits

- Select Slits to open the simulation and select these choices in order:

- Type of wave: pick one that looks like a bullet

- Frequency (middle green)

- Amplitude: max

- Check Screen

- Choose 2 Slits

- Slit width 200

- Slit separation 400

- Click the Green button.

You will see light/dark patterns moving toward the screen. The light zones arise from constructive interference and dark from destructive interference of the two waves as they emerge from the slits.

Simulation 2: Diffraction

Now, look at the diffraction pattern from light moving through simple and more complex openings and interacting with an object using the PHET animation and the step below.

- First, refresh the browser window.

- Select Diffraction to open the simulation and select these choices in order.

- Pick 450 nm wavelength.

- Choose in succession the four vertical icons (circle, square, circle/square, array of circles, person).

- Observe the diffraction patterns as you change the slit size.

X-ray scattering can also be viewed as light "reflecting" from a series of planes formed by atoms in the crystal, with the planes separated by specific distances (in the Angstrom range). The x-rays that are "reflected" from innumerable planes recombine constructively and destructively to form a diffraction pattern. X rays are used since the size of the "slits", and the distance between these "reflective" planes, must be comparable to the wavelength of the incident light, which for x-rays is 0.5 – 2.5 Å.

A diffraction pattern is mathematically decoded to form an electron density map, since electrons scatter X-rays. Hydrogen atoms don't appear in X-ray crystal structures because they lack sufficient electrons to serve as effective scattering centers. Computer programs are used to fit the electron density map to a 3D arrangement of atoms separated by characteristic bond distances corresponding to the functional groups and side chains found in proteins. The quality/amount of crystals helps determine the quality of the diffraction pattern and the resulting structure. X-ray crystallographers define quality in terms of resolution. A resolution of 5 Å - 10 Å can reveal the structure of polypeptide chains, 3 Å - 4 Å of groups of atoms, and 1 Å - 1.5 Å of individual atoms.

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) shows the process from crystal to model.

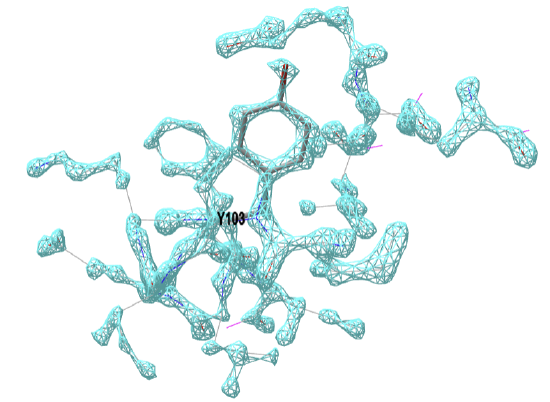

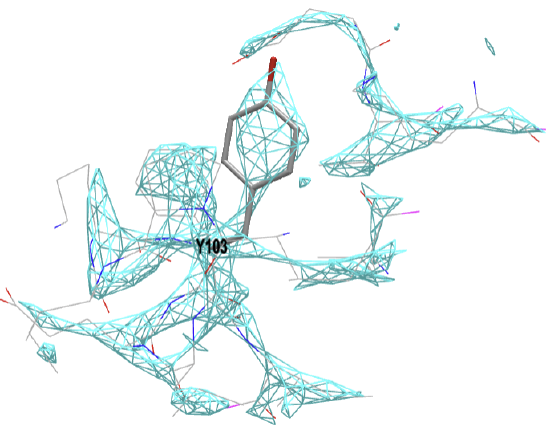

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) below shows the electron density map around tyrosine 103 from myoglobin from crystal structures at two different resolutions (left, 1a6m, 1.0 Å resolution and right, 108m, 2.7 Å resolution).

|

|

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\): Electron density map around tyrosine 103 from myoglobin from crystal structures at two different resolutions (left, 1a6m, 1.0 Å resolution and right, 108m, 2.7 Å resolution). Click on the images to see full iCn3D models showing the electron density map around the Y103. (Choice of Y103 from https://pdb101.rcsb.org/learn/guide-...ata/resolution)

This figure shows 2Fo-Fc electron density maps, which use the observed diffraction data (Fo) and the diffraction data calculated from the atomic model (Fc). Proteopedia has an excellent description of electron density maps.

Not all proteins can be readily crystallized. The process is, in many ways, an art as much as it is a science. Membrane proteins fall into this category.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

Many readers have probably performed 1H-NMR on small molecules in introductory and organic chemistry labs. Interpreting spectra of molecules with many hydrogen atoms in straight and branched chains, in rings, and in functional groups is not simple. Imagine doing that to determine the structure of a small protein with 1000s of hydrogen atoms! The spectrum would be essentially indecipherable. Luckily, multi-dimensional NMR techniques have allowed the solution (not crystal) structure of small proteins to be determined. These methods are outside of the scope of this book. For those interested in more detail, read A Brief Introduction to NMR Spectroscopy of Proteins by Poulsen.

Let's briefly introduce a 2D NMR peak for a simple molecule, ethyl acetate. The 1D 1H-NMR spectrum for the molecule is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\).

Now, let's show a simulated 2D COSY spectrum of the same molecule. The image and explanation below are adapted from Structure & Reactivity in Organic, Biological, and Inorganic Chemistry by Chris Schaller, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. Structure and Reactivity

In homonuclear correlation spectroscopy (COSY), we can look for hydrogens that are coupled to each other. In ethyl acetate, it's pretty clear where they are. There is a quartet and a triplet; the hydrogens corresponding to those two peaks are probably beside each other in the structure. The COSY spectrum takes that 1H spectrum and spreads it into two dimensions. Instead of being displayed as a row of peaks, the peaks are spread out into a 2D array. Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) shows an annotated simulated COSY spectrum. The peaks are displayed along one axis, and the same peaks are displayed along the other.

What does it mean to be coupled? It means that magnetic information is transmitted between the atoms. How can we tell? Essentially, we can send a pulse of electromagnetic radiation into one set of hydrogen atoms and look for a response elsewhere. Of course, if we send a pulse of radio waves at a frequency that a particular hydrogen will absorb, we will see a response in that hydrogen itself. That's why we see the peaks on the diagonal (dotted line). The peaks along the diagonal in the spectra (1.26, 1.26; 2.04, 2.04; 4.12, 4.12) don't provide any new information, since they are the main peaks in the 1D NMR.

However, we also see responses from other hydrogen atoms magnetically linked to the original one. They give the peaks (shown as purple circles) that do not appear along the diagonal. Those peaks indicate which hydrogens are coupled to which other hydrogens. The hydrogens at 1.26 ppm are coupled to the ones at 4.12 ppm, giving a "cross-peak" at (1.26, 4.12). There is also a cross-peak at (4.12, 1.26) because that relationship goes both ways.

This coupling should make sense because the protons that give the signals at 4.12 (-O-CH2-CH3) and 1.26 (-CH2-CH3) are on adjacent carbons and split each other's signals, as seen in the 1D NMR. This example shows how we can identify which protons in a 2D NMR spectrum are coupled through 3 bonds (H-C-C-H), a critical piece of information for determining protein structures by NMR.

Variants of 2D NMR are also used in protein structure. They use NMR-active nuclei in addition to 1H, including 13C (natural abundance 1%) and 15N (natural abundance 0.37%). Given these low abundances, proteins for NMR structure determination are often purified in cells grown in media enriched in 13C and 15N precursors.

HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation) and HMQC (Heteronuclear Multiple Quantum Coherence): Just as COSY spectra show which protons are coupled to each other, HMBC (and the related HMQC) give information about the relative relationships between protons and carbons in a structure. In an HMQC spectrum, a 13C spectrum is displayed on one axis and a 1H spectrum on the other. Cross-peaks show which proton is attached to which carbon. COSY spectra show a 3-bond coupling (from H-C-C-H), whereas HMQC shows a 1-bond coupling (just C-H).

Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) Spectroscopy (NOESY): This technique shows through-space interactions within the molecule rather than the through-bond interactions in COSY and HMBC/HMBQ. This method is especially useful for determining a molecule's stereochemical relationships. In two stereoisomers, all atoms are connected in the same order by the same bonds. A COSY or an HMBC spectrum couldn't distinguish between these isomers.

HNCA: This is an example of 3D NMR. It shows a correlation between an amide proton, the amide nitrogen to which it is attached, and the carbons attached to the amide nitrogen. HNCA data are viewed in slices, where you examine one nitrogen at a time. One axis shows the shift of the proton attached to that nitrogen, and the other axis shows the shifts of the carbons attached to the nitrogen. The abbreviation HNCA comes from the pathway for transferring magnetization (amide H to amide N, then to the attached C-alpha).

NMR structures in the Protein Data Bank consist of many slightly different structures. This arises from the dynamic behavior of the proteins in water, compared to when the structure is determined from a crystal. Comparative analyses between crystal and NMR structures show that secondary structures are equally accurate, that loops in NMR structures are probably too flexible, and that loops in protein, often on the surface, are too rigid, which makes sense given the packing restraints with a crystal lattice.

Cryo-electron Microscopy

Cryogenic-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has recently emerged as a powerful structural biology technique that delivers high-resolution density maps of macromolecular structures. Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) shows a cryo-EM and structure determined from it.

Resolutions approaching 1.5 Å are now possible, and maps in the 1–4-Å range inform the construction of atomistic models with high confidence. This new capacity for investigators to determine macromolecular structures at high resolution and without the need to form crystals has led to an explosion of interest in adopting cryo-EM.

Protein suspensions are frozen on 3-mm-diameter transmission-electron microscope (TEM) support grids made from a conductive material (e.g., Cu or Au) that are coated with a carbon film with a regular array of perforations 1–2 μm in diameter. A total of 3–5 μl of sample is loaded onto the grid, which is then immediately blotted with filter paper to create a film of buffer/protein on the grid that, when frozen, will be thin enough for the electron beam to penetrate. Optimizing ice thickness is a vital step in sample preparation, as thicker ice layers increase the likelihood that an incident electron will undergo multiple scattering, thereby reducing image quality. In the case of extreme ice thickness, the electron beam does not penetrate at all. After blotting, the grid is rapidly plunged into a bath of liquid ethane—a very effective cryogen that freezes water rapidly enough to prevent ice crystal formation. Forming a vitreous ice layer is the fundamental step in cryo-EM and preserves the target in a near-native state. The resulting vitreous ice layer with suspended protein molecules must then remain close to liquid nitrogen temperature (− 196 °C) during storage and TEM imaging to prevent phase changes to other types of ice that are not amenable to high-quality imaging and preservation of protein structure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\) summarizes the process and single particle structure determination.

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\): Principle of cryo-EM and single-particle reconstruction. Agirrezabala, X., Frank, J., 2010. From DNA to proteins via the ribosome: Structural insights into the workings of the translation machinery. Human Genomics 4, 226. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-7364-4-4-226. CC BY 4.0

The figure above shows the cryoEM structure-determination process for ribosomes. When frozen, they are found in random orientations embedded in a thin layer of ice. Exposure to a low-dose electron beam in the transmission electron microscope produces a projection image (i.e., the electron micrograph). A typical electron micrograph shows E. coli ribosomes as low-contrast single particles on a noisy background. After the orientations of the particles have been determined, usually by matching them to a reference using computer algorithms, they are used to reconstruct a density map using back-projection or a similar reconstruction algorithm. This density map is segmented into components (subunits, ligands), and these components are displayed in different colors in a surface representation (bottom panel; small and large subunits are shown in yellow and blue, respectively). A- and P-site tRNAs are colored red, pink, and green, respectively.

Given the increasing popularity of this technique, we present Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\) below, which shows another representation of the end-point of a higher-resolution 3D model.

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\): A schematic of the single-particle reconstruction cryoEM pipeline. Hey Tony et al., 2020. Machine learning and big scientific data. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A.3782019005420190054. http://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2019.0054. Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Motion occurs when the beam strikes the ice dome, where the single structure is found. Motion pictures are captured with fast detectors, and computers are used to compensate for motion, which reduces the resolution of the structure. In addition, as X-rays damage molecules, so can electron beams. Earlier frames in the movie show less damage. The beam's motion and damage effects can now be corrected to increase the resolution.

Here is a YouTube video from PDB 101 that describes the technique.

Methods for determining atomic structure. PDB-101: Educational resources supporting molecular explorations through biology and medicine. Christine Zardecki, Shuchismita Dutta, David S. Goodsell, Robert Lowe, Maria Voigt, Stephen K. Burley. (2022) Protein Science 31: 129-140 https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.4200. CC By 4.0 license.

A new chapter section, 4.14: Predicting Structure from Sequence and Sequence from Structure/Function (New 10/24), has been created to reorganize material on predicting protein structure from sequence and the reverse problem: predicting sequence from protein structure (for designer proteins) and from protein function.

Comparisons of 3D Structure Determination Methods

Obtaining a pure, highly concentrated (mM) protein sample is a major bottleneck for X-ray crystallography and NMR. The high concentration is required because both techniques are insensitive to single-molecule analysis, and a large population of a particular protein is required to overcome the signal-to-noise barrier. Similarly, the sample needs to be very homogeneous, so protein purification is necessary at some point. Cryo-EM requires considerably less protein than the other two methods, but still a lot by any standard. Typically, Cryo-EM requires preparations at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in a volume of at least 50 μl. In contrast, crystal formation might require 500 μl of protein at 5 -10 mg/ml concentration. Cryo-Em requires the protein to be prepared in a low-salt buffer solution with minimal additives to ensure good freezing and image contrast.

Recombinant protein production using E. coli is the method of choice when large quantities of protein are required. This process involves cloning the gene (often cDNA) encoding the protein of interest into a suitable inducible vector, transforming the vector into an E. coli host, and growing the culture in a rich medium. The bacterial host will multiply during a growth phase, after which it is induced to express the protein of interest. If all goes well, the protein will be soluble and expressed at high levels. Unfortunately, this process is easier said than done. Many eukaryotic proteins do not express well in prokaryotic hosts, and modifications are needed to optimize the bacterial host, codon usage, media, etc., to obtain a decent yield of recombinant protein.

Additionally, expressed proteins are often found as insoluble inclusion bodies and require high concentrations (2M to 8M) of denaturants such as urea or guanidine hydrochloride to solubilize them, followed by stepwise dialysis into an appropriate buffer to refold them. Alternatively, eukaryotic organisms such as S. cerevisiae (yeast), insect, and mammalian cell lines can be used, especially if post-translational modifications are studied. However, yield decreases and overall costs increase are common with these organisms.

Protein production is difficult for 15N- and 13C- NMR because proteins must be labeled with these isotopes. Only these isotopes have nuclei with + ½ and -½ spin states, which enable the energy transitions required for a radiofrequency NMR signal. Of course, 1H also has ½ spin states but is highly abundant.