4.3: Eukaryotic Cells

- Page ID

- 1840

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Skills to Develop

- Describe the structure of eukaryotic cells

- Compare animal cells with plant cells

- State the role of the plasma membrane

- Summarize the functions of the major cell organelles

Have you ever heard the phrase “form follows function?” It’s a philosophy practiced in many industries. In architecture, this means that buildings should be constructed to support the activities that will be carried out inside them. For example, a skyscraper should be built with several elevator banks; a hospital should be built so that its emergency room is easily accessible.

Our natural world also utilizes the principle of form following function, especially in cell biology, and this will become clear as we explore eukaryotic cells (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Unlike prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells have: 1) a membrane-bound nucleus; 2) numerous membrane-bound organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, chloroplasts, mitochondria, and others; and 3) several, rod-shaped chromosomes. Because a eukaryotic cell’s nucleus is surrounded by a membrane, it is often said to have a “true nucleus.” The word “organelle” means “little organ,” and, as already mentioned, organelles have specialized cellular functions, just as the organs of your body have specialized functions.

At this point, it should be clear to you that eukaryotic cells have a more complex structure than prokaryotic cells. Organelles allow different functions to be compartmentalized in different areas of the cell. Before turning to organelles, let’s first examine two important components of the cell: the plasma membrane and the cytoplasm.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

If the nucleolus were not able to carry out its function, what other cellular organelles would be affected?

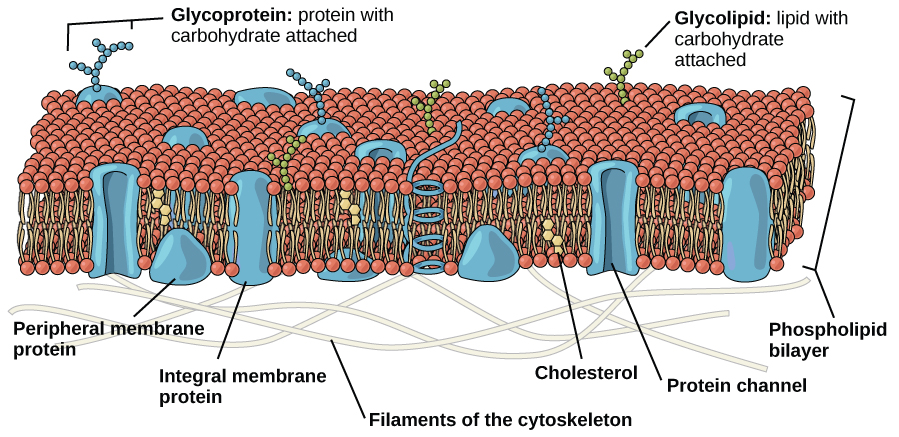

The Plasma Membrane

Like prokaryotes, eukaryotic cells have a plasma membrane (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins that separates the internal contents of the cell from its surrounding environment. A phospholipid is a lipid molecule with two fatty acid chains and a phosphate-containing group. The plasma membrane controls the passage of organic molecules, ions, water, and oxygen into and out of the cell. Wastes (such as carbon dioxide and ammonia) also leave the cell by passing through the plasma membrane.

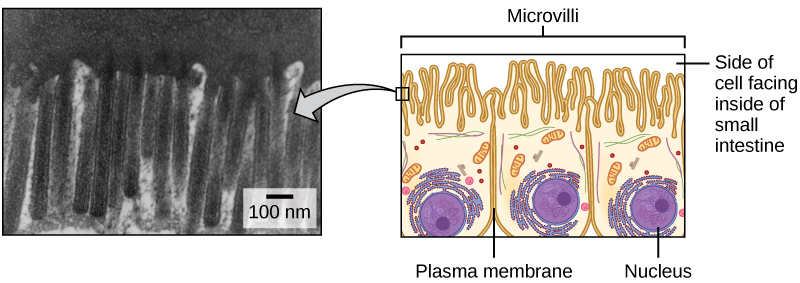

The plasma membranes of cells that specialize in absorption are folded into fingerlike projections called microvilli (singular = microvillus); (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Such cells are typically found lining the small intestine, the organ that absorbs nutrients from digested food. This is an excellent example of form following function. People with celiac disease have an immune response to gluten, which is a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. The immune response damages microvilli, and thus, afflicted individuals cannot absorb nutrients. This leads to malnutrition, cramping, and diarrhea. Patients suffering from celiac disease must follow a gluten-free diet.

The Cytoplasm

The cytoplasm is the entire region of a cell between the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope (a structure to be discussed shortly). It is made up of organelles suspended in the gel-like cytosol, the cytoskeleton, and various chemicals (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Even though the cytoplasm consists of 70 to 80 percent water, it has a semi-solid consistency, which comes from the proteins within it. However, proteins are not the only organic molecules found in the cytoplasm. Glucose and other simple sugars, polysaccharides, amino acids, nucleic acids, fatty acids, and derivatives of glycerol are found there, too. Ions of sodium, potassium, calcium, and many other elements are also dissolved in the cytoplasm. Many metabolic reactions, including protein synthesis, take place in the cytoplasm.

The Nucleus

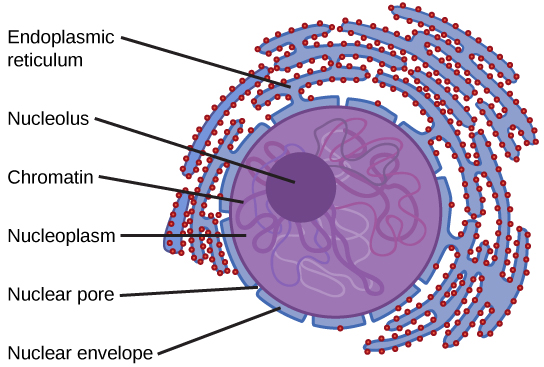

Typically, the nucleus is the most prominent organelle in a cell (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The nucleus (plural = nuclei) houses the cell’s DNA and directs the synthesis of ribosomes and proteins. Let’s look at it in more detail (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

The Nuclear Envelope

The nuclear envelope is a double-membrane structure that constitutes the outermost portion of the nucleus (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Both the inner and outer membranes of the nuclear envelope are phospholipid bilayers.

The nuclear envelope is punctuated with pores that control the passage of ions, molecules, and RNA between the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm. The nucleoplasm is the semi-solid fluid inside the nucleus, where we find the chromatin and the nucleolus.

Chromatin and Chromosomes

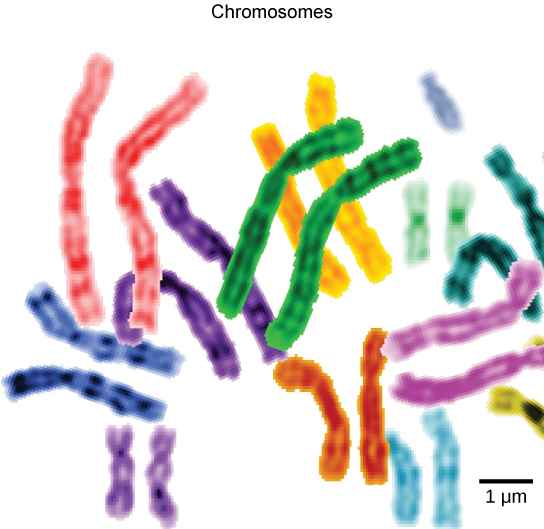

To understand chromatin, it is helpful to first consider chromosomes. Chromosomes are structures within the nucleus that are made up of DNA, the hereditary material. You may remember that in prokaryotes, DNA is organized into a single circular chromosome. In eukaryotes, chromosomes are linear structures. Every eukaryotic species has a specific number of chromosomes in the nuclei of its body’s cells. For example, in humans, the chromosome number is 46, while in fruit flies, it is eight. Chromosomes are only visible and distinguishable from one another when the cell is getting ready to divide. When the cell is in the growth and maintenance phases of its life cycle, proteins are attached to chromosomes, and they resemble an unwound, jumbled bunch of threads. These unwound protein-chromosome complexes are called chromatin (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)); chromatin describes the material that makes up the chromosomes both when condensed and decondensed.

The Nucleolus

We already know that the nucleus directs the synthesis of ribosomes, but how does it do this? Some chromosomes have sections of DNA that encode ribosomal RNA. A darkly staining area within the nucleus called the nucleolus (plural = nucleoli) aggregates the ribosomal RNA with associated proteins to assemble the ribosomal subunits that are then transported out through the pores in the nuclear envelope to the cytoplasm.

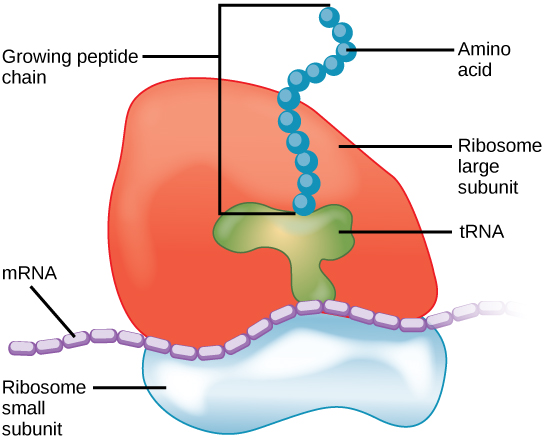

Ribosomes

Ribosomes are the cellular structures responsible for protein synthesis. When viewed through an electron microscope, ribosomes appear either as clusters (polyribosomes) or single, tiny dots that float freely in the cytoplasm. They may be attached to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane or the cytoplasmic side of the endoplasmic reticulum and the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Electron microscopy has shown us that ribosomes, which are large complexes of protein and RNA, consist of two subunits, aptly called large and small (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Ribosomes receive their “orders” for protein synthesis from the nucleus where the DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA travels to the ribosomes, which translate the code provided by the sequence of the nitrogenous bases in the mRNA into a specific order of amino acids in a protein. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins.

Because proteins synthesis is an essential function of all cells (including enzymes, hormones, antibodies, pigments, structural components, and surface receptors), ribosomes are found in practically every cell. Ribosomes are particularly abundant in cells that synthesize large amounts of protein. For example, the pancreas is responsible for creating several digestive enzymes and the cells that produce these enzymes contain many ribosomes. Thus, we see another example of form following function.

Mitochondria

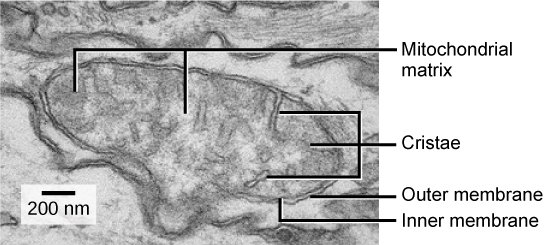

Mitochondria (singular = mitochondrion) are often called the “powerhouses” or “energy factories” of a cell because they are responsible for making adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s main energy-carrying molecule. ATP represents the short-term stored energy of the cell. Cellular respiration is the process of making ATP using the chemical energy found in glucose and other nutrients. In mitochondria, this process uses oxygen and produces carbon dioxide as a waste product. In fact, the carbon dioxide that you exhale with every breath comes from the cellular reactions that produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

In keeping with our theme of form following function, it is important to point out that muscle cells have a very high concentration of mitochondria that produce ATP. Your muscle cells need a lot of energy to keep your body moving. When your cells don’t get enough oxygen, they do not make a lot of ATP. Instead, the small amount of ATP they make in the absence of oxygen is accompanied by the production of lactic acid.

Mitochondria are oval-shaped, double membrane organelles (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)) that have their own ribosomes and DNA. Each membrane is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins. The inner layer has folds called cristae. The area surrounded by the folds is called the mitochondrial matrix. The cristae and the matrix have different roles in cellular respiration.

Peroxisomes

Peroxisomes are small, round organelles enclosed by single membranes. They carry out oxidation reactions that break down fatty acids and amino acids. They also detoxify many poisons that may enter the body. (Many of these oxidation reactions release hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, which would be damaging to cells; however, when these reactions are confined to peroxisomes, enzymes safely break down the H2O2 into oxygen and water.) For example, alcohol is detoxified by peroxisomes in liver cells. Glyoxysomes, which are specialized peroxisomes in plants, are responsible for converting stored fats into sugars.

Vesicles and Vacuoles

Vesicles and vacuoles are membrane-bound sacs that function in storage and transport. Other than the fact that vacuoles are somewhat larger than vesicles, there is a very subtle distinction between them: The membranes of vesicles can fuse with either the plasma membrane or other membrane systems within the cell. Additionally, some agents such as enzymes within plant vacuoles break down macromolecules. The membrane of a vacuole does not fuse with the membranes of other cellular components.

Animal Cells versus Plant Cells

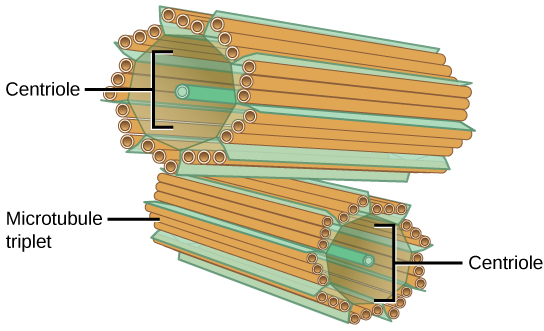

At this point, you know that each eukaryotic cell has a plasma membrane, cytoplasm, a nucleus, ribosomes, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and in some, vacuoles, but there are some striking differences between animal and plant cells. While both animal and plant cells have microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs), animal cells also have centrioles associated with the MTOC: a complex called the centrosome. Animal cells each have a centrosome and lysosomes, whereas plant cells do not. Plant cells have a cell wall, chloroplasts and other specialized plastids, and a large central vacuole, whereas animal cells do not.

The Centrosome

The centrosome is a microtubule-organizing center found near the nuclei of animal cells. It contains a pair of centrioles, two structures that lie perpendicular to each other (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Each centriole is a cylinder of nine triplets of microtubules.

The centrosome (the organelle where all microtubules originate) replicates itself before a cell divides, and the centrioles appear to have some role in pulling the duplicated chromosomes to opposite ends of the dividing cell. However, the exact function of the centrioles in cell division isn’t clear, because cells that have had the centrosome removed can still divide, and plant cells, which lack centrosomes, are capable of cell division.

Lysosomes

Animal cells have another set of organelles not found in plant cells: lysosomes. The lysosomes are the cell’s “garbage disposal.” In plant cells, the digestive processes take place in vacuoles. Enzymes within the lysosomes aid the breakdown of proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles. These enzymes are active at a much lower pH than that of the cytoplasm. Therefore, the pH within lysosomes is more acidic than the pH of the cytoplasm. Many reactions that take place in the cytoplasm could not occur at a low pH, so again, the advantage of compartmentalizing the eukaryotic cell into organelles is apparent.

The Cell Wall

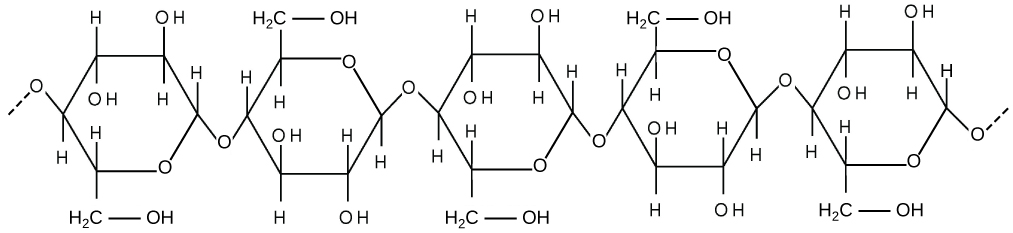

If you examine Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)b, the diagram of a plant cell, you will see a structure external to the plasma membrane called the cell wall. The cell wall is a rigid covering that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell. Fungal and protistan cells also have cell walls. While the chief component of prokaryotic cell walls is peptidoglycan, the major organic molecule in the plant cell wall is cellulose (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)), a polysaccharide made up of glucose units. Have you ever noticed that when you bite into a raw vegetable, like celery, it crunches? That’s because you are tearing the rigid cell walls of the celery cells with your teeth.

Chloroplasts

Like the mitochondria, chloroplasts have their own DNA and ribosomes, but chloroplasts have an entirely different function. Chloroplasts are plant cell organelles that carry out photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is the series of reactions that use carbon dioxide, water, and light energy to make glucose and oxygen. This is a major difference between plants and animals; plants (autotrophs) are able to make their own food, like sugars, while animals (heterotrophs) must ingest their food.

Like mitochondria, chloroplasts have outer and inner membranes, but within the space enclosed by a chloroplast’s inner membrane is a set of interconnected and stacked fluid-filled membrane sacs called thylakoids (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Each stack of thylakoids is called a granum (plural = grana). The fluid enclosed by the inner membrane that surrounds the grana is called the stroma.

The chloroplasts contain a green pigment called chlorophyll, which captures the light energy that drives the reactions of photosynthesis. Like plant cells, photosynthetic protists also have chloroplasts. Some bacteria perform photosynthesis, but their chlorophyll is not relegated to an organelle.

Evolution Connection: Endosymbiosis

We have mentioned that both mitochondria and chloroplasts contain DNA and ribosomes. Have you wondered why? Strong evidence points to endosymbiosis as the explanation.

Symbiosis is a relationship in which organisms from two separate species depend on each other for their survival. Endosymbiosis (endo- = “within”) is a mutually beneficial relationship in which one organism lives inside the other. Endosymbiotic relationships abound in nature. We have already mentioned that microbes that produce vitamin K live inside the human gut. This relationship is beneficial for us because we are unable to synthesize vitamin K. It is also beneficial for the microbes because they are protected from other organisms and from drying out, and they receive abundant food from the environment of the large intestine.

Scientists have long noticed that bacteria, mitochondria, and chloroplasts are similar in size. We also know that bacteria have DNA and ribosomes, just as mitochondria and chloroplasts do. Scientists believe that host cells and bacteria formed an endosymbiotic relationship when the host cells ingested both aerobic and autotrophic bacteria (cyanobacteria) but did not destroy them. Through many millions of years of evolution, these ingested bacteria became more specialized in their functions, with the aerobic bacteria becoming mitochondria and the autotrophic bacteria becoming chloroplasts.

The Central Vacuole

Previously, we mentioned vacuoles as essential components of plant cells. If you look at Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)b, you will see that plant cells each have a large central vacuole that occupies most of the area of the cell. The central vacuole plays a key role in regulating the cell’s concentration of water in changing environmental conditions. Have you ever noticed that if you forget to water a plant for a few days, it wilts? That’s because as the water concentration in the soil becomes lower than the water concentration in the plant, water moves out of the central vacuoles and cytoplasm. As the central vacuole shrinks, it leaves the cell wall unsupported. This loss of support to the cell walls of plant cells results in the wilted appearance of the plant.

The central vacuole also supports the expansion of the cell. When the central vacuole holds more water, the cell gets larger without having to invest a lot of energy in synthesizing new cytoplasm.

Summary

Like a prokaryotic cell, a eukaryotic cell has a plasma membrane, cytoplasm, and ribosomes, but a eukaryotic cell is typically larger than a prokaryotic cell, has a true nucleus (meaning its DNA is surrounded by a membrane), and has other membrane-bound organelles that allow for compartmentalization of functions. The plasma membrane is a phospholipid bilayer embedded with proteins. The nucleus’s nucleolus is the site of ribosome assembly. Ribosomes are either found in the cytoplasm or attached to the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane or endoplasmic reticulum. They perform protein synthesis. Mitochondria participate in cellular respiration; they are responsible for the majority of ATP produced in the cell. Peroxisomes hydrolyze fatty acids, amino acids, and some toxins. Vesicles and vacuoles are storage and transport compartments. In plant cells, vacuoles also help break down macromolecules.

Animal cells also have a centrosome and lysosomes. The centrosome has two bodies perpendicular to each other, the centrioles, and has an unknown purpose in cell division. Lysosomes are the digestive organelles of animal cells.

Plant cells and plant-like cells each have a cell wall, chloroplasts, and a central vacuole. The plant cell wall, whose primary component is cellulose, protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell. Photosynthesis takes place in chloroplasts. The central vacuole can expand without having to produce more cytoplasm.

Art Connections

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): If the nucleolus were not able to carry out its function, what other cellular organelles would be affected?

- Answer

-

Free ribosomes and rough endoplasmic reticulum (which contains ribosomes) would not be able to form.

Glossary

- cell wall

- rigid cell covering made of cellulose that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell

- central vacuole

- large plant cell organelle that regulates the cell’s storage compartment, holds water, and plays a significant role in cell growth as the site of macromolecule degradation

- centrosome

- region in animal cells made of two centrioles

- chlorophyll

- green pigment that captures the light energy that drives the light reactions of photosynthesis

- chloroplast

- plant cell organelle that carries out photosynthesis

- chromatin

- protein-DNA complex that serves as the building material of chromosomes

- chromosome

- structure within the nucleus that is made up of chromatin that contains DNA, the hereditary material

- cytoplasm

- entire region between the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope, consisting of organelles suspended in the gel-like cytosol, the cytoskeleton, and various chemicals

- cytosol

- gel-like material of the cytoplasm in which cell structures are suspended

- eukaryotic cell

- cell that has a membrane-bound nucleus and several other membrane-bound compartments or sacs

- lysosome

- organelle in an animal cell that functions as the cell’s digestive component; it breaks down proteins, polysaccharides, lipids, nucleic acids, and even worn-out organelles

- mitochondria

- (singular = mitochondrion) cellular organelles responsible for carrying out cellular respiration, resulting in the production of ATP, the cell’s main energy-carrying molecule

- nuclear envelope

- double-membrane structure that constitutes the outermost portion of the nucleus

- nucleolus

- darkly staining body within the nucleus that is responsible for assembling the subunits of the ribosomes

- nucleoplasm

- semi-solid fluid inside the nucleus that contains the chromatin and nucleolus

- nucleus

- cell organelle that houses the cell’s DNA and directs the synthesis of ribosomes and proteins

- organelle

- compartment or sac within a cell

- peroxisome

- small, round organelle that contains hydrogen peroxide, oxidizes fatty acids and amino acids, and detoxifies many poisons

- plasma membrane

- phospholipid bilayer with embedded (integral) or attached (peripheral) proteins, and separates the internal content of the cell from its surrounding environment

- ribosome

- cellular structure that carries out protein synthesis

- vacuole

- membrane-bound sac, somewhat larger than a vesicle, which functions in cellular storage and transport

- vesicle

- small, membrane-bound sac that functions in cellular storage and transport; its membrane is capable of fusing with the plasma membrane and the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus