7.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 123364

A few genera of bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium have the ability to produce resistant survival forms termed endospores. Unlike the reproductive spores of fungi and plants, these endospores are resistant to heat, drying, radiation, and various chemical disinfectants (see Labs 17 and 18)

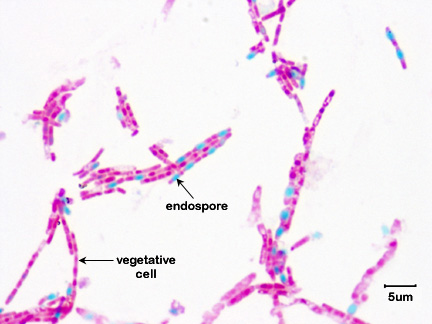

Endospore formation (sporulation) occurs through a complex series of events. One is produced within each vegetative bacterium. Once the endospore is formed, the vegetative portion of the bacterium is degraded and the dormant endospore is released. ( See Fig. \(\PageIndex{1}\).)

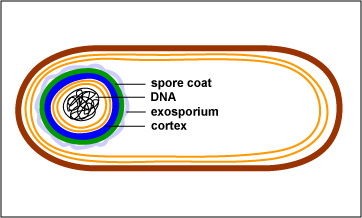

First the DNA replicates and a cytoplasmic membrane septum forms at one end of the cell. A second layer of cytoplasmic membrane then forms around one of the DNA molecules (the one that will become part of the endospore) to form a forespore. Both of these membrane layers then synthesize peptidoglycan in the space between them to form the first protective coat, the cortex. Calcium dipocolinate is also incorporated into the forming endospore. A spore coat composed of a keratin-like protein then forms around the cortex. Sometimes an outer membrane composed of lipid and protein and called an exosporium is also seen (Fig. \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Finally, the remainder of the bacterium is degraded and the endospore is released. Sporulation generally takes around 15 hours.

Click here to view an electron micrograph of an endospore of Bacillus stearothermophilus, at the Microbe Zoo web page of Michigan State University.

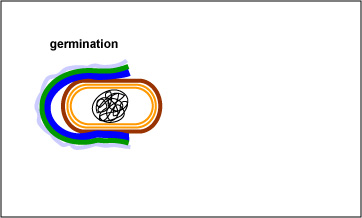

The endospore is able to survive for long periods of time until environmental conditions again become favorable for growth. The endospore then germinates, producing a single vegetative bacterium (see Fig. \(\PageIndex{3}\) and \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

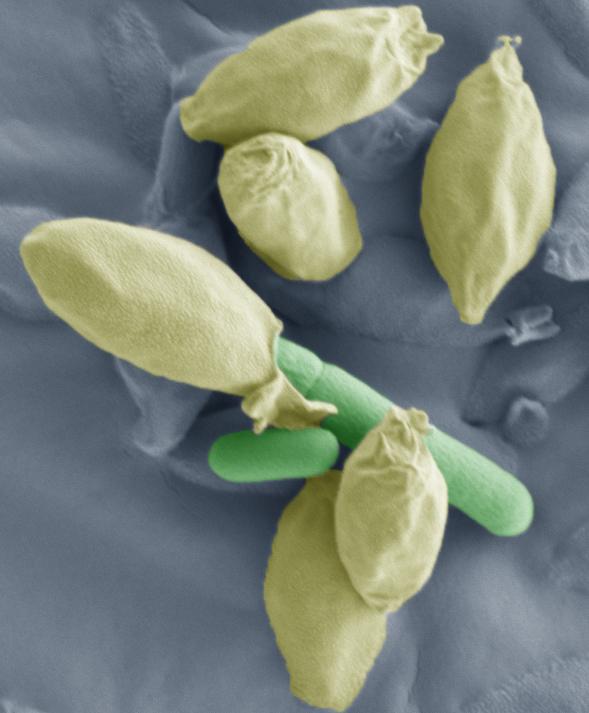

| Fig. \(\PageIndex{3}\): Endospore Germination | Fig. \(\PageIndex{4}\): Germination of an endospore of Clostridium sporogenes |

|---|---|

|

|

| With the proper environmental stimuli, the endospore germinates. As the protective layers of the endospore are enzymatically broken down, a vegetative bacterium begins to form and emerge. | Note the bacillus-shaped vegetative cell emerging from the endospores. |

| (Copyright; Gary E. Kaiser, Ph.D. The Community College of Baltimore County, Catonsville Campus CC-BY-3.0) | |

Bacterial endospores are resistant to antibiotics, most disinfectants, and physical agents such as radiation, boiling, and drying. The impermeability of the spore coat is thought to be responsible for the endospore's resistance to chemicals. The heat resistance of endospores is due to a variety of factors:

- Calcium-dipicolinate, abundant within the endospore, may stabilize and protect the endospore's DNA.

- Specialized DNA-binding proteins saturate the endospore's DNA and protect it from heat, drying, chemicals, and radiation.

- The cortex may osmotically remove water from the interior of the endospore and the dehydration that results is thought to be very important in the endospore's resistance to heat and radiation.

- Finally, DNA repair enzymes contained within the endospore can repair damaged DNA during germination.

Although harmless themselves until they germinate, bacterial endospores are involved in the transmission of some diseases to humans. Infections transmitted to humans by endospores include:

Contributors and Attributions

Dr. Gary Kaiser (COMMUNITY COLLEGE OF BALTIMORE COUNTY, CATONSVILLE CAMPUS)