6.2: Fundamentals of Plate Tectonics

- Page ID

- 69395

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Plate tectonics is the model or theory that has been used for the past 60 years to understand and explain how the Earth works—more specifically the origins of continents and oceans, of folded rocks and mountain ranges, of earthquakes and volcanoes, and of continental drift.

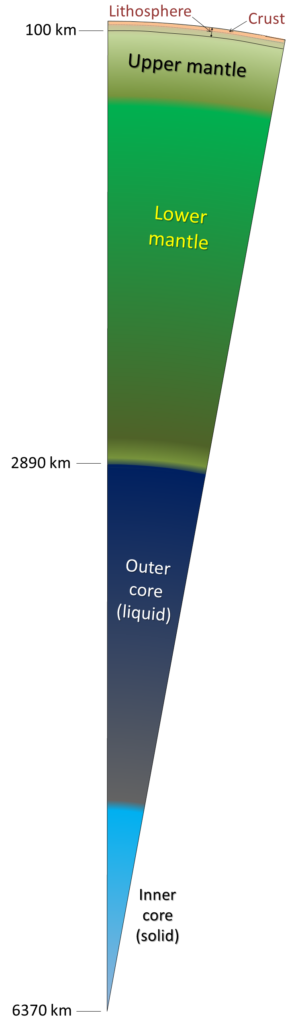

Key to understanding plate tectonics is an understanding of Earth’s internal structure, which is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Earth’s core consists mostly of iron. The outer core is hot enough for the iron to be liquid. The inner core—although even hotter—is under so much pressure that it is solid. The mantle is made up of iron and magnesium silicate minerals. The bulk of the mantle surrounding the outer core is solid rock, but is plastic enough to be able to flow slowly. The outermost part of the mantle is rigid. The crust—composed mostly of granite on the continents and mostly of basalt beneath the oceans—is also rigid. The crust and outermost rigid mantle together make up the lithosphere. The lithosphere is divided into about 20 tectonic plates that move in different directions on Earth’s surface.

The core extends down to the center of the earth, a depth of about 6400 km from the surface (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The core makes up 16 percent of the volume of the earth and about 31 percent of the mass. It can be divided into two regions: a solid inner core and a liquid outer core. The inner core is probably mostly metallic iron alloyed with a small amount of nickel, as its density is somewhat greater than that of pure metallic iron. The outer core is similar in composition, but probably also contains small amounts of lighter elements, such as sulfur and oxygen, because its density is slightly less than that of pure metallic iron. The presence of the lighter elements depresses the freezing point and is probably responsible for the outer core's liquid state.

The mantle is the largest layer in the earth, making up about 82 percent of the volume and 68 percent of the mass of the earth (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The mantle is dominated by magnesium and iron-rich (mafic) minerals. Heat from the core of the earth is transported to the crustal region by large-scale convection in the mantle. Near the top of the mantle is a region of partially melted rock called the asthenosphere. Numerous small-scale convection currents occur here as hot magma (i.e., molten rock) rises and cooler magma sinks due to differences in density.The mantle extends down to a depth of 2900 km where the core begins.

The crust is the thinnest layer in the earth, extending downward from the surface to an average depth of 35 km, making up only 1 percent of the mass and 2 percent of the volume (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Relative to the rest of the earth, the crust is rich in elements such as silicon, aluminum, calcium, sodium and potassium. Crustal materials are very diverse, consisting of more than 2000 minerals. The less dense crust floats upon the mantle in two forms: the continental crust and the oceanic crust. The oceanic crust, which contains more mafic minerals is thinner and denser than the continental crust which contains minerals richer in silicon and aluminum. The thick continental crust has deep buoyant roots that help to support the higher elevations above. The crust contains the mineral resources and the fossil fuels used by humans.

An important property of Earth (and other planets) is that the temperature increases with depth, from close to 0°C at the surface to about 7000°C at the centre of the core. In the crust, the rate of temperature increase is about 30°C every kilometre. This is known as the geothermal gradient.

Heat is continuously flowing outward from Earth’s interior, and the transfer of heat from the core to the mantle causes convection in the mantle (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). This convection is the primary driving force for the movement of tectonic plates. At places where convection currents in the mantle are moving upward, new lithosphere forms (at ocean ridges), and the plates move apart (diverge). Where two plates are converging (and the convective flow is downward), one plate will be subducted (pushed down) into the mantle beneath the other. Many of Earth’s major earthquakes and volcanoes are associated with convergent boundaries.

Earth’s major tectonic plates and the directions and rates at which they are diverging at sea-floor ridges, are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). A convergent (colliding) plate boundary occurs when two plates collide. If the convergent boundary involves two continental plates, the crust is compressed into high mountain ranges such as the Himalayas. If an oceanic plate and a continental plate collide, the oceanic crust (because it is more dense) is subducted under the continental crust. The region where subduction takes place is called a subduction zone and usually results in a deep ocean trench such as the "Mariana Trench" in the western Pacific ocean. The subducted crust melts and the resultant magma can rise to the surface and form a volcano. A divergent plate boundary occurs when two plates move away from each other. Magma upwelling from the mantle region is forced through the resulting cracks, forming new crust. The mid-ocean ridge in the Atlantic ocean is a region where new crustal material continually forms as plates diverge. Volcanoes can also occur at divergent boundaries. The island of Iceland is an example of such an occurrence. A third type of plate boundary is the transform boundary. This occurs when two plates slide past one another. This interaction can build up strain in the adjacent crustal regions, resulting in earthquakes when the strain is released. The San Andreas Fault in California is an example of a transform plate boundary.

Using either a map of the tectonic plates from the Internet or Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) determine which tectonic plate you are on right now, approximately how fast it is moving, and in what direction. How far has that plate moved relative to Earth’s core since you were born?

Contributors and Attributions

Modified by Kyle Whittinghill from the following sources

- Fundamentals of Plate Tectonics from Physical Geology by Steven Earle (licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License)

- The Solid Earth from AP Environmental Science by University of California College Prep