9.4: Polysaccharides

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 154245

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Search Fundamentals of Biochemistry

Learning Goals (ChatGPT o1, 1/30/25)

-

Define and Differentiate Carbohydrates and Glycans:

- Distinguish among the terms “sugar,” “carbohydrate,” and “glycan,” and explain how these concepts encompass everything from simple monosaccharides to highly complex glycan polymers.

-

Understand Monosaccharide Structure and Representation:

- Describe the chemical structure of monosaccharides, including key features such as stereochemistry, the formation of cyclic (pyranose and furanose) structures, and the distinction between α- and β-anomers.

- Convert between different structural representations (Fischer projections, Haworth projections, chair and wedge/dash forms) and understand how these representations inform our perception of 3D carbohydrate conformation.

-

Glycosidic Linkages and Polymer Structure:

- Explain the mechanism of glycosidic bond formation (hemiacetal and acetal formation) and describe how different linkage types (e.g., α 1,4, α 1,6, β 1,4) give rise to the structural diversity of polysaccharides.

- Compare and contrast homopolymers such as starch, glycogen, dextran, cellulose, and chitin in terms of their linkage types, branching patterns, and overall 3D conformation.

-

Structure–Function Relationships in Storage vs. Structural Polysaccharides:

- Discuss how the type of glycosidic linkage (e.g., α in starch/glycogen versus β in cellulose/chitin) influences the polymer’s physical properties, biological roles (energy storage vs. structural support), and digestibility.

- Analyze the role of branching (e.g., α 1,6 linkages in glycogen and amylopectin) in enhancing solubility and rapid mobilization of stored glucose.

-

Utilizing Symbolic Nomenclature for Glycans (SNFG):

- Learn and apply the SNFG system to accurately represent glycan structures using specific colors and shapes, facilitating clear communication of complex carbohydrate architectures.

-

3D Conformational Analysis and Modeling:

- Interpret interactive 3D models and computer-generated representations (e.g., iCn3D models) of polysaccharide fragments to understand their tertiary and quaternary arrangements, such as the helical structures of V-amylose or the fiber assembly in cellulose.

-

Exploration of Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs):

- Identify the structure and function of key GAGs (e.g., hyaluronic acid, keratan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate, and heparin) and describe how variations in disaccharide repeat units and sulfation patterns contribute to their biological roles, such as in extracellular matrix composition and cell signaling.

-

Comparative Structural Analysis in Biological Contexts:

- Contrast the molecular structures of polysaccharides from different biological sources (e.g., cellulose in plants versus chitin in invertebrates) and discuss the impact of subtle structural differences (e.g., the presence of N-acetyl groups) on function.

-

Practical and Clinical Implications:

- Understand the physiological significance of polysaccharide structure in energy storage (glycogen and starch) and structural support (cellulose, chitin, and GAGs) and discuss how these structures influence their biochemical properties, such as solubility and reactivity.

- Explore real-world applications, such as the use of iodine staining in starch detection, the role of glycogenin in glycogen synthesis, and the impact of dietary glycans on human health (e.g., Neu5Gc incorporation).

Achieving these goals will equip students with the fundamental and advanced concepts needed to analyze and interpret the structural and functional diversity of carbohydrates and glycans in biological systems.

Polysaccharides contain many monosaccharides in glycosidic links and may have many branches. They serve as either structural components or energy storage molecules. Polysaccharides consisting of single monosaccharides are homopolymers. Starch, glycogen, dextran, cellulose, and chitin are the most common. We'll discuss based on whether the acetal link is alpha or beta.

α 1,4 main chain links

Starch and Glycogen: These polysaccharides are polymers of glucose linked in α 1,4 links with α 1,6 branches. Starch, found in plants, is subdivided into amylose, which has no branches, and amylopectin, which does. Starch granules consist of about 20% amylose and 80% amylopectin. Glycogen, the main CHO storage in animals, is found in muscle and liver and consists of glucose residues in α 1,4 links with lots of α 1,6 branches (many more branches than in starch).

Here are various ways to render in 2D the chemical structure of a branched glycogen and starch fragment, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

The top part of the figure shows the Haworth structure. The bottom part shows two glucose units in red and blue in the more structurally clear chair and wedge/dash representations.

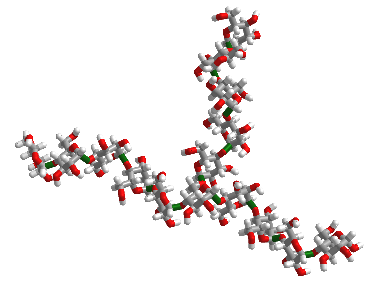

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of 10 glucose monosaccharides in an α-(1,4) linkage with five glucose units with α-(1,4) linkages attached to the main chain through an α-(1,6) branch at glucose 6 of the main chain. The type of substructure would be found in starch (amylopectin) and glycogen.

_linked_glucose_with_an_%25CE%25B1-(1%252C6)_branch.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=336&height=259) I

I

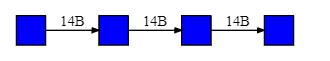

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the structure in the iCn3D model in a diagrammatic fashion in which glucose is represented as a blue circle with the acetal/glycosidic/glucosidic linkages between the monosaccharides written between the circles. The 14A label shows that the acetal linkage is an α-(1,4) link with a single α-(1,6) branch.

The linkages are written in a variety of conventions. These include 14A, 14α, 4A and 4α. The link between many sugars is often a 1,x link where x is 2,3, 4, 5, or 6. In those cases, the number 1 can be omitted. The program-generated images in this text use numbers and A or B.

What makes carbohydrates so complex is their 3D structures. Like proteins and nucleic acids, they can adopt a myriad of conformations. As the monomeric units are so homogeneous, especially in homopolymers, it can be difficult to obtain crystal structures for them, so computer models are often used.

Studies have shown that the simple starch fraction amylose, an α 1,4 polymer of glucose, often envisioned as a straight chain, can adopt three main conformations. They are double-helical A- (found chiefly in cereals), double helical B-(found primarily on tubers) amyloses, and single-helical V-amylose (or simply A, B, and V structures). The A and B do NOT represent alpha or beta in this classification system. The A and B forms consist of double helices aligned in a parallel fashion with about six glucose residues per turn. The helices appear to be left or right-handed, and this ambiguity might arise from a lack of crystal structures.

In contrast, a well-defined structure of the V helix is known. It folds into a left-handed helix with six glucose residues per turn and a pitch of about 8Å. Unlike alpha helices of proteins and the double-stranded helix of DNA, the center of the helix is NOT packed tightly and can accommodate small molecules. One is iodine (triiodide, I3-), which exhibits a dark blue color when bound in amylose in starch. This is the basis for starch indicators that you may have used in titration reactions in biology and chemistry courses.

Alpha helices might self-associate during folding in proteins to form a 4-helix bundle. Likewise, the helices in V-amylose can associate into bundles. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the actual structure of a V-amylose, cycloamylose 26 (1C58). It consists of a linear cycloamylose strand of 26 glucose monomers, which has collapsed to form secondary structure with 6-residue helices packed together into a tertiary structure of 4-helix bundle. The blue sphere "cartoon" color coding of each glucose residue corresponds to the blue circles in the diagrammatic representation above.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=372&height=291)

Rotate the model to explore it. Trace the chains by following the blue sphere symbolic representation of glucose as you trace the main chain. Rotate it to view down the helix axes to see the four holes that can each accommodate an I3-. In the menu button (=), choose Style, Chemicals, Sphere to see a spacefilling model that shows the holes within each helix. Remember, NO unoccupied holes exist within either a protein alpha helix or a double-stranded DNA molecule.

The well-known macrocyclic compound cyclodextrins (for example, α-cyclodextrin) are structures equivalent to one turn of V-amylose. The V-amylose helix is partially stabilized by hydrogen bonds from donors and acceptors within the helix from the OH3 on the ith glucose and the OH2 on the i+1th glucose, as well as from the OH6 on the ith glucose and the OH2 on the i+6th glucose.

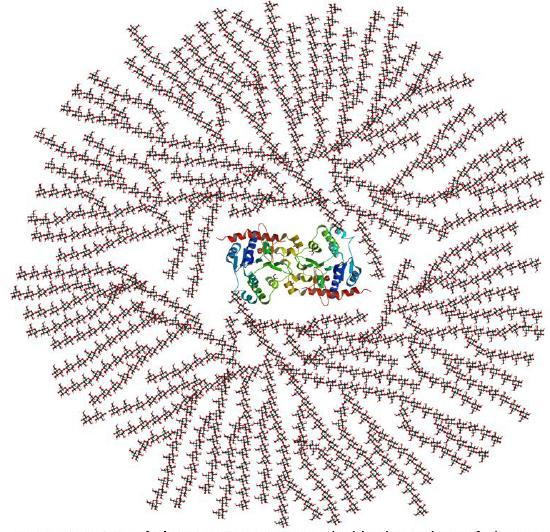

In vivo, glycogen is synthesized by attaching glucose monomers to a core protein called glycogenin. Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows a model of a glycogen particle with glycogenin at its core.

The dimeric protein glycogenin is an enzyme that autoglucosylates itself stepwise. The first glucose is added at Tyr 195. At some point, the active site must get buried, and the protein can no longer add more monomers.

Storing glucose residues as either glycogen or starch, one large molecule, makes chemical sense. A review of colligative properties would inform you that if glucose were stored as the monosaccharide, a great osmotic pressure difference would be found between the outside and inside of the cell. Glycogen, with its many branches, is a single molecule. When glucose is needed, it is cleaved one residue at a time from all the branches (at the nonreducing ends) of glycogen, producing a large amount of free glucose quickly.

Phi/Psi angles can also be used in Ramachandran plots to show the conformations around the acetal link for the starch/glycogen main chain in a fashion comparable to that for proteins (around the alpha carbon). The phi torsion angle describes rotation around the C1-O bond of the acetal link, and the psi angle describes rotation around the O-C4 bond of the same acetal link, with the glucopyranose ring considered as a rigid rotator (just as the six atoms in the planar peptide bond unit). The most extended form of a glucose polymer occurs when the glycosidic link is β 1,4 (as in cellulose), which forms linear chains. This would be analogous to the more extended parallel beta strand (phi/psi angles of -1190, -1130) and antiparallel beta strands (phi/psi angles of -1390, +1350) of proteins. The α 1,4-linked main chain of glycogen and starch causes the chain to turn and form a large helix. Iodine (or I3-) can fit into the helix, which turns a solution/suspension of starch blue, which turns starch purple. The less extended structure is analogous to the less extended protein alpha helix, which has phi/psi angles of -570,-470.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) shows phi/psi angles for acetal/glycosidic linkage in maltose, a disaccharide of glucose, as shown below.

α 1,6 main chain links

Dextran is a branched polymer of glucose in α 1,6 links with α 1,2, α 1,3, or α 1,4 linked side chains. This polymer is used in some chromatography resins. Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows chair structures (A) and wedge/dash structures (B) for dextran, showing the main chain α 1,6 link with one α 1,3 branch.

Depending on its molecular weight, it is soluble in water (forming viscous solutions) and organic solvents. It is also used as a food thickener and stabilizer. It is synthesized by lactic acid-forming bacteria using sucrose as an energy source. Most uses are commercial.

β 1,4 links

Cellulose, a structural homopolymer of glucose in plants, has β 1,4 main chain links without branching. Multiple chains are held together by intra- and inter-chain H-bonds. It is the most abundant biological molecule in nature. Various renderings of 4 glucose residues in cellulose are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\). Haworth structures are not shown. Instead, more chemically informative chairs and wedge/dash structures are used. It's important to see the structures displayed in many ways since different representations of carbohydrate structures can be found in different sources.

In A, the most common chair representation, the 2nd and 4th residues from the right-hand end are flipped versions of residues 1 and 3. Residues 1 and 2 are colored red and blue for clarity. This unit is repeated to generate the full chain. The top part of A shows a simplified version of the flip of the red ring to produce the blue ring to help you see that they are indeed identical structures.

The same structure as in A is shown in the left part of B in wedge/dash from (looking down on the ring). The right-hand side of B shows a variant of B's left-hand side generated by a simple 1800 rotation around the bond indicated on the left of B.

The simple repeat is shown in C without the chain flips in A and B. The acetal/glycosidic/glucosidic bond seems to be shown in a straight line in the chair structures (a bit confusing and structurally deceptive), but more clearly in the adjacent wedge/dash structure.

All structures are correct, but the one shown in A is most often used.

One long chain can interact with other chains in a structure stabilized by intrachain and interchain hydrogen bonds. Different sources display different hydrogen bonds. Some common ones are shown below. These chains align in parallel and twist to form larger cellulose fibers. Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of cellulose chains.

In addition, hydrophobic interactions occur between adjacent planes of cellulose strands. How can that be, considering the strongly polar nature of glucose and a single cellulose strand? Figure \(\PageIndex{9B}\): below, with two representations of cellulose, shows how axial hydrogens project vertically from the plane of the glucose monomer rings to form a weak but biologically significant hydrophobic surface.

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Two representations showing the nonpolar axial surface of cellulose strands that contribute to hydrophobic interactions stabilizing the cellulose assemblies. The top panel shows how cellulose could interact with a nonpolar planar substance, such as a layer of graphite. Axial H atoms are shown in green/cyan in the bottom panel.

Top Panel: Yang G, Luo X and Shuai L (2021) Bioinspired Cellulase-Mimetic Solid Acid Catalysts for Cellulose Hydrolysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9:770027. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.770027. Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY).

Bottom Panel: Uusi-Tarkka, E.-K.; Skrifvars, M.; Haapala, A. Fabricating Sustainable All-Cellulose Composites. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app112110069. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

The glycan is the major component in the exoskeletons of anthropoids and mollusks. It is a β 1,4-linked polymer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc). Compare this with cellulose, which is a β 1,4-linked polymer of glucose. What a difference an N-acetyl substituent makes!

The basic chemical structure of chitin is shown in chair form in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) along with the symbolic nomenclature for glycans (SNFG).

Symbolic nomenclature for glycans (SNFG) -

Before we go further into the complexities of glycan structure, let's explore the symbolic nomenclature for glycan structures. The Consortium for Functional Glycomics (2005) proposed a scheme based on specific colored geometric shapes for each, as shown for the example glycan shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) for a complex glycan.

This nomenclature has recently been updated in Appendix 1B of Essentials of Glycobiology, 3rd Edition (Glycobiology 25(12): 1323-1324, 2015. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv091 (PMID 26543186) and is summarized in the Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

Glycosaminoglycans - Heteropolysaccharides with Disaccharide Repeating Units

Many polysaccharides consist of repeating disaccharide units. A major class of polysaccharides with disaccharide repeats includes the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), all of which contain one amino sugar in the repeat, and in which one or both of the sugars contain negatively charged sulfate and/or carboxyl groups. The extent and position of sulfation vary widely between and within GAGs. GAGs are found in the vitreous humor of the eye and synovial fluid of joints, as well as in connective tissue like tendons, cartilage, etc., and skin. They are found in the extracellular matrix and are often covalently attached to proteins to form proteoglycans. From a bird's eye view, they are all elongated polyanions.

They and their structures are very complicated and exceedingly diverse. This makes it difficult for those who want unambiguous structures. From a biological perspective, they present in their local environment an incredibly diverse array of potential binding sites for ligands (both small and large). Because of these, they also have functions in cell signaling. In addition, some GAGs are free-standing, while others are covalently attached to proteins (like glycogen is attached to glycogenin). These large molecules are called proteoglycans. We will discuss this later in Chapter 7.4 when we discuss the "carbohydrate code."

Here are the ring structures and descriptions of important GAGs. The common disaccharide repeat unit is shown twice for each structure, with the knowledge that sulfation patterns may differ for the disaccharide repeats in the actual chains. Note also that the first member of each disaccharide repeat shows the ring flipped vertically (top to bottom) as was shown in the structures for other beta-linked glycans (cellulose, chitin) above.

In a long chain, selecting which is the repeating disaccharide unit is a bit relative, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) for the repeating disaccharide sequence of N-acetylglucosamine (blue square) and N-acetylgalactosamine (yellow square).

At the top, the repeating units (blue-yellow) are connected through beta 1,4 links, while at the bottom, the connection of the repeating unit (yellow-blue) is beta 1,3. The best way to annotate the repeating unit without knowing the full chain is elusive. What's most important, however, is to note the alternating acetal/glycosidic links throughout the whole sequence. In the figures below, different disaccharide repeats are highlighted.

Hyaluronic acid

This is a polymer of glucuronate (β 1,3) GlcNAc. It offers a backbone for the attachment of proteins and other GAGs. It's the only GAG without sulfate. Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows a tetrasaccharide fragment with two disaccharide repeats. The illustrated disaccharide repeat's internal acetal/glycosidic link is β 1,3, while the disaccharide's connection is β 1,4. For one last time, the vertical flip of the glucuronic acid is shown to allow a better understanding of its flipped presentation in the actual GAG.

Hyaluronic acids are found in a variety of locations, including synovial fluid, the extracellular matrix, and skin, where they help control skin moisture. It is water-soluble and displays twin antiparallel left-oriented helices. Covalent conjugates of the chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and camptothecin linked to hyaluronic acid, whose overall structure is similar to "worm-like micelles", have been used successfully to treat skin cancers.

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of hyaluronic acid (4HYA). The dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds.

Three calcium ions are shown as well. The SNFG cartoon is also illustrated.

Keratan sulfate

This GAG contains repeats of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate in β 1,3 link to D-galactose or D-galactose-6-sulfate. The link between Gal and the modified glucosamine is β 1,4. Keratin sulfate is most abundant in the cornea of the eye as well as in other connective tissues such as bone, cartilage, and tendon, as well as in the central and peripheral nervous system.

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) shows a tetrasaccharide containing two repeating disaccharides.

Chondroitin sulfate

The repeat disaccharide unit is D-glucuronate β(1,4) GalNAc-4 or 6-sulfate. It's found in connective tissue matrix, the cell surface (in the form of proteoglycans), basement membranes, and intracellular granules. Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) shows a tetrasaccharide showing two disaccharide repeats.

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of chondroitin-4-sulfate (1C4S). The dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds.

Dermatan sulfate

This glycosaminoglycan is similar to chondroitin sulfate. It is first made as a polymer of the disaccharide unit of D-gluconic and N-acetyl-D-galactosamine. The gluconic acid is epimerized to L-iduronic acid, followed by sulfation. Its structure is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\).

Heparin

This GAG contains a highly trisulfated disaccharide repeat, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\). Note that the molecule can contain glucuronate or iduronate, and the degree of sulfation of the chains varies. Remember, no genetic code specifies these polymers' sequence or sulfation pattern.

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the solution structure of an 18-mer of heparin (3IRI). The dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds.

Most people are familiar with the anti-clotting properties of heparin administered as a drug. Heparin acts as a "catalyst" to accelerate the inhibition of the enzyme thrombin, which cleaves fibrinogen and activates platelets to form clots by the blood protein antithrombin III. Heparin works in two ways to facilitate thrombin inactivation. It has a specific binding site for antithrombin III, which causes a conformational change in the protein, making it a more effective inhibitor. Thrombin, a positively-charged serine protease, can nonspecifically bind heparin, a polyanion. When it does, it diffuses along the heparin chain, where it can find bound antithrombin III much quicker than if the inhibitor were free in the blood. Heparin effectively changes the search path of thrombin from a 3D to a 1D search.

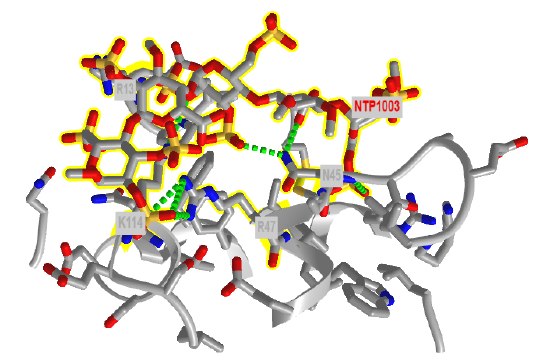

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the amino acids in antithrombin III within seven angstroms of a bound heparin 5mer (1NQ9). Dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between the two. Heparin is highlighted in yellow

Agarose

Agarose is the main polysaccharide component derived from red algae. Agarose is a polymer of a disaccharide repeat of (1,3)-β-D-galactopyranose-(1,4)-3,6-anhydro-α-L-galactopyranose, is often used for a gelable solid phase for electrophoresis of nucleic acid and as a component of chromatography beads. As with starch, a mixture of amylose and amylopectin, agarose is often found with agaropectin, a sulfated galactan. A tetrasaccharide fragment with two disaccharide repeats is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the agarose double helix (1AGA). The dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds within the polymer.

Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\): Agarose double helix (1AGA). (Copyright; author via source). Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...5nnzm9XcPogMz7

In the iCn3D model, choose Style, Glycan, Show Cartoon to see the yellow sphere for galactose.

Summary

This chapter delves into the intricate world of carbohydrate biochemistry, emphasizing the remarkable complexity and diversity of polysaccharides. It highlights the challenges in studying glycans due to the stereochemical complexity of monosaccharides, the variability of glycosidic linkages, and the lack of a direct genetic template for glycan synthesis. Key themes include:

-

Fundamental Building Blocks:

- The chapter begins by reviewing the structure of monosaccharides, including their linear (Fischer projections) and cyclic forms (Haworth, chair, and wedge/dash representations). Emphasis is placed on the formation of pyranose and furanose rings and the significance of α and β anomers, which influence both structure and function.

-

Glycosidic Linkages and Polysaccharide Assembly:

- Glycosidic bonds are the chemical linkages that join monosaccharide units into polymers. The discussion covers the differences between α and β linkages and their consequences for the overall conformation of the polysaccharide.

- Homopolymers such as starch, glycogen, dextran, cellulose, and chitin are introduced. Starch and glycogen, composed of glucose units linked by α 1,4 bonds with branching via α 1,6 linkages, serve as energy storage molecules. In contrast, cellulose and chitin, linked by β 1,4 bonds, form rigid, linear structures that provide mechanical support in plant cell walls and exoskeletons, respectively.

-

Structural Representations and Models:

- Various methods for depicting carbohydrate structures are discussed, including two-dimensional diagrams (e.g., Haworth and Fischer projections) and symbolic nomenclature (SNFG) that uses colored shapes to represent different monosaccharides.

- The chapter utilizes interactive 3D models to illustrate the spatial arrangement of branched glycogen and starch fragments, emphasizing how subtle differences in linkage and branching affect three-dimensional conformation and biological function.

-

Functional Implications:

- The structural diversity of polysaccharides is directly linked to their biological roles. Energy storage polysaccharides like glycogen and starch must be compact and highly branched to allow rapid mobilization of glucose, while structural polysaccharides like cellulose and chitin form extensive networks stabilized by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions.

- The chapter also touches on glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are heteropolysaccharides with repeating disaccharide units. These molecules, often attached to proteins as proteoglycans, play critical roles in cellular signaling and the formation of the extracellular matrix.

-

Biological and Clinical Relevance:

- Understanding the complexity of carbohydrate structures is essential for insights into cellular function, tissue architecture, and even clinical conditions. For example, variations in sialic acid structures can influence cell recognition and immunity, while dietary components such as glycans impact overall health.

Overall, this chapter provides a comprehensive overview of the chemical, structural, and functional properties of polysaccharides. By integrating detailed structural representations with biological context, it lays the groundwork for further study in glycobiology and its applications in health and disease.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=526&height=202)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=202&height=333)