Section 3.2: Isomerism

- Page ID

- 142800

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Explain the concept of isomerism

- Distinguish between structural isomers and enantiomers

Organic Molecules

Organic molecules in organisms are generally larger and more complex than inorganic molecules. Their carbon skeletons are held together by covalent bonds. They form the cells of an organism and perform the chemical reactions that facilitate life. All of these molecules, called biomolecules because they are part of living matter, contain carbon, which is the building block of life. Carbon is a very unique element in that it has four valence electrons in its outer orbitals and can form four single covalent bonds with up to four other atoms at the same time (see Appendix A). These atoms are usually oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorous, and carbon itself; the simplest organic compound is methane, in which carbon binds only to hydrogen (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

As a result of carbon’s unique combination of size and bonding properties, carbon atoms can bind together in large numbers, thus producing a chain or carbon skeleton. The carbon skeleton of organic molecules can be straight, branched, or ring shaped (cyclic). Organic molecules are built on chains of carbon atoms of varying lengths; most are typically very long, which allows for a huge number and variety of compounds. No other element has the ability to form so many different molecules of so many different sizes and shapes.

Isomerism

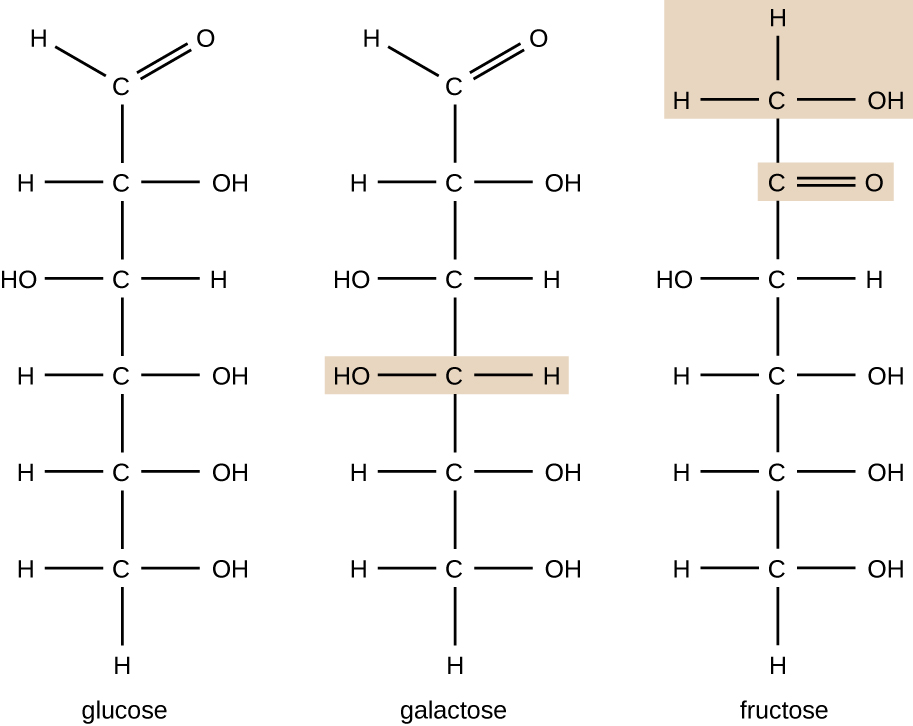

Molecules with the same atomic makeup but different structural arrangement of atoms are called isomers. The concept of isomerism is very important in chemistry because the structure of a molecule is always directly related to its function. Slight changes in the structural arrangements of atoms in a molecule may lead to very different properties. Chemists represent molecules by their structural formula, which is a graphic representation of the molecular structure, showing how the atoms are arranged. Compounds that have identical molecular formulas but differ in the bonding sequence of the atoms are called structural isomers. The monosaccharides glucose, galactose, and fructose all have the same molecular formula, C6H12O6, but we can see from Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) that the atoms are bonded together differently.

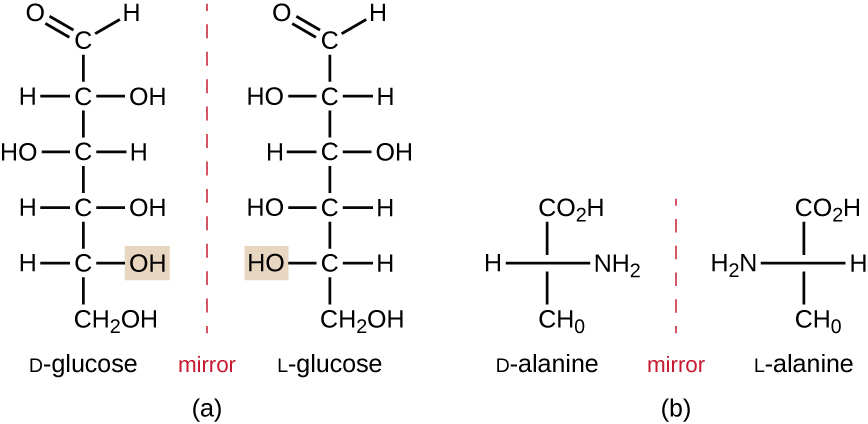

Isomers that differ in the spatial arrangements of atoms are called stereoisomers; one unique type is enantiomers. The properties of enantiomers were originally discovered by Louis Pasteur in 1848 while using a microscope to analyze crystallized fermentation products of wine. Enantiomers are molecules that have the characteristic of chirality, in which their structures are nonsuperimposable mirror images of each other. Chirality is an important characteristic in many biologically important molecules, as illustrated by the examples of structural differences in the enantiomeric forms of the monosaccharide glucose or the amino acid alanine (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Many organisms are only able to use one enantiomeric form of certain types of molecules as nutrients and as building blocks to make structures within a cell. Some enantiomeric forms of amino acids have distinctly different tastes and smells when consumed as food. For example, L-aspartame, commonly called aspartame, tastes sweet, whereas D-aspartame is tasteless. Drug enantiomers can have very different pharmacologic affects. For example, the compound methorphan exists as two enantiomers, one of which acts as an antitussive (dextromethorphan, a cough suppressant), whereas the other acts as an analgesic (levomethorphan, a drug similar in effect to codeine).

Enantiomers are also called optical isomers because they can rotate the plane of polarized light. Some of the crystals Pasteur observed from wine fermentation rotated light clockwise whereas others rotated the light counterclockwise. Today, we denote enantiomers that rotate polarized light clockwise (+) as d forms, and the mirror image of the same molecule that rotates polarized light counterclockwise (−) as the l form. The d and l labels are derived from the Latin words dexter (on the right) and laevus (on the left), respectively. These two different optical isomers often have very different biological properties and activities. Certain species of molds, yeast, and bacteria, such as Rhizopus, Yarrowia, and Lactobacillus spp., respectively, can only metabolize one type of optical isomer; the opposite isomer is not suitable as a source of nutrients. Another important reason to be aware of optical isomers is the therapeutic use of these types of chemicals for drug treatment, because some microorganisms can only be affected by one specific optical isomer.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Key Concepts and Summary

- Life is carbon based. Each carbon atom can bind to another one producing a carbon skeleton that can be straight, branched, or ring shaped.

- The same numbers and types of atoms may bond together in different ways to yield different molecules called isomers. Isomers may differ in the bonding sequence of their atoms (structural isomers) or in the spatial arrangement of atoms whose bonding sequences are the same (stereoisomers), and their physical and chemical properties may vary slightly or drastically.