15.1: The Genetic Code

- Page ID

- 70075

The Central Dogma: DNA Encodes RNA; RNA Encodes Protein

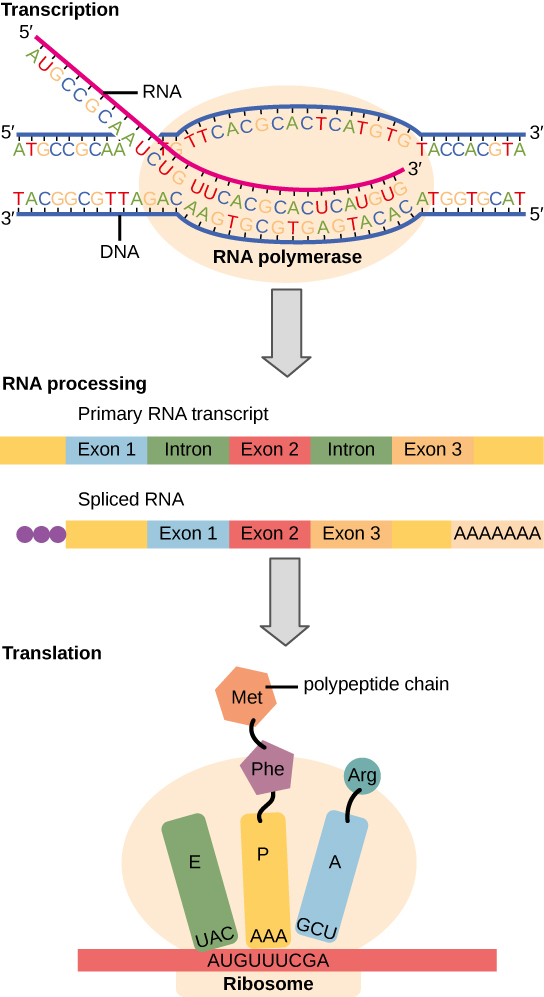

To summarize what we know to this point, the cellular process of transcription generates messenger RNA (mRNA), a mobile molecular copy of one or more genes with an alphabet of A, C, G, and uracil (U). Translation of the mRNA template converts nucleotide-based genetic information into a protein product. This flow of genetic information in cells from DNA to mRNA to protein is described by the Central Dogma (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), which states that genes specify the sequence of mRNAs, which in turn specify the sequence of proteins. The decoding of one molecule to another is performed by specific proteins and RNAs. Because the information stored in DNA is so central to cellular function, it makes intuitive sense that the cell would make mRNA copies of this information for protein synthesis, while keeping the DNA itself intact and protected.

It turns out that the central dogma is not always true. We will not discuss the exceptions here, however.

Amino Acid Structure

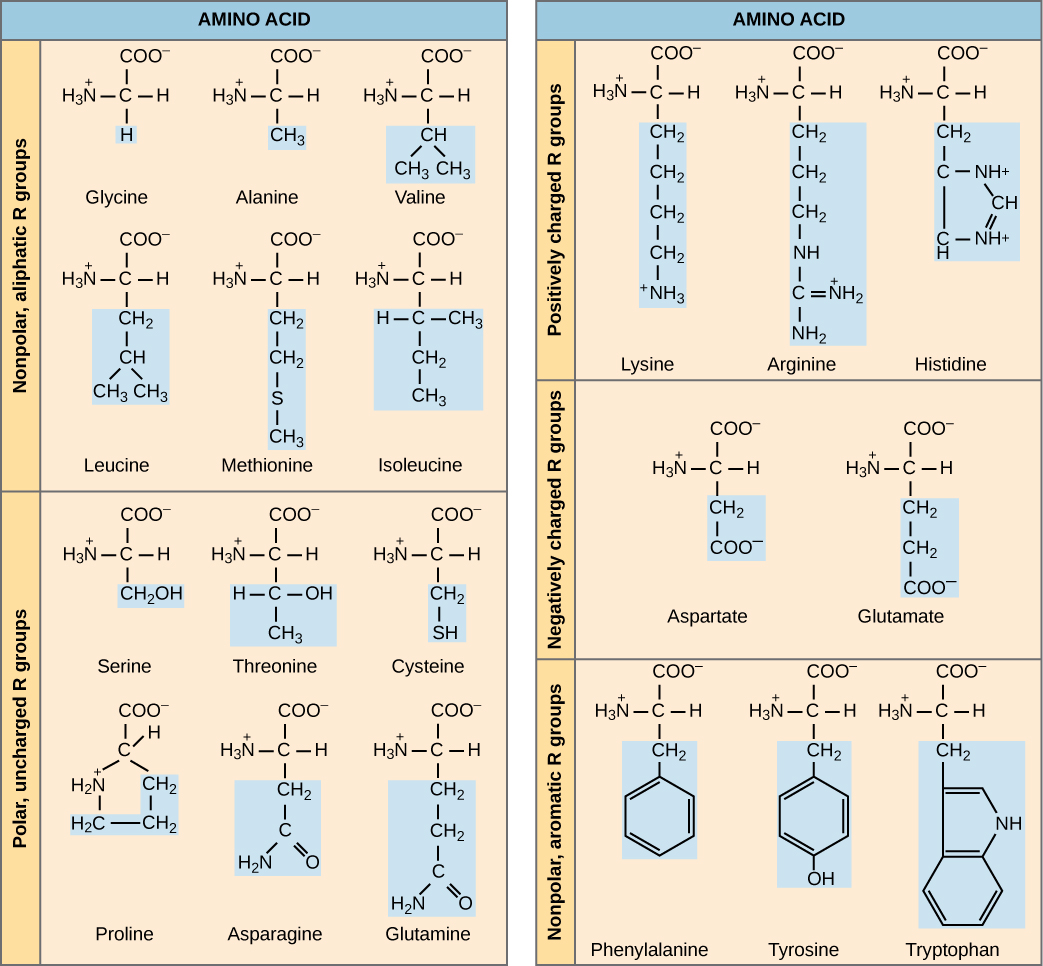

Protein sequences consist of 20 commonly occurring amino acids (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)); therefore, it can be said that the protein alphabet consists of 20 letters. Different amino acids have different chemistries (such as acidic versus basic, or polar and non-polar) and different structural constraints. Variation in amino acid sequence gives rise to enormous variation in protein structure and function.

Genetic Code

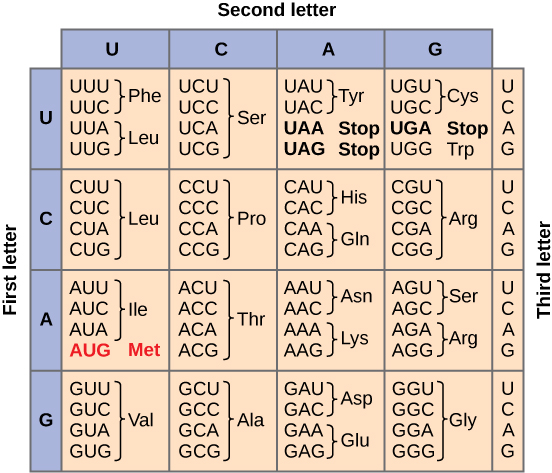

Each amino acid is defined by a three-nucleotide sequence called the triplet codon. The relationship between a nucleotide codon and its corresponding amino acid is called the genetic code. Given the different numbers of “letters” in the mRNA (4 – A, U, C, G) and protein “alphabets” (20 different amino acids) one nucleotide could not correspond to one amino acid. Nucleotide doublets would also not be sufficient to specify every amino acid because there are only 16 possible two-nucleotide combinations (42). In contrast, there are 64 possible nucleotide triplets (43), which is far more than the number of amino acids. Scientists theorized that amino acids were encoded by nucleotide triplets and that the genetic code was degenerate. In other words, a given amino acid could be encoded by more than one nucleotide triplet (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). These nucleotide triplets are called codons.

The same codon will always specify the insertion of one specific amino acid. The chart seen in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) can be used to translate an mRNA sequence into an amino acid sequence. For example, the codon UUU will always cause the insertion of the amino acid phenylalanine (Phe), while the codon UUA will cause the insertion of leucine (Leu).

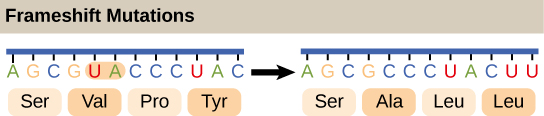

Each set of three bases (one codon) causes the insertion of one specific amino acid into the growing protein. This means that the insertion of one or two nucleotides can completely change the triplet “reading frame”, thereby altering the message for every subsequent amino acid (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Though insertion of three nucleotides causes an extra amino acid to be inserted during translation, the integrity of the rest of the protein is maintained.

Three of the 64 codons terminate protein synthesis and release the polypeptide from the translation machinery. These triplets are called stop codons. Another codon, AUG, also has a special function. In addition to specifying the amino acid methionine, it also serves as the start codon to initiate translation. The reading frame for translation is set by the AUG start codon near the 5′ end of the mRNA. The genetic code is universal. With a few exceptions, virtually all species use the same genetic code for protein synthesis, which is powerful evidence that all life on Earth shares a common origin.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. January 2, 2017 https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10...fig-ch15_01_05