6.2: The Transcription of DNA into RNA

- Page ID

- 4834

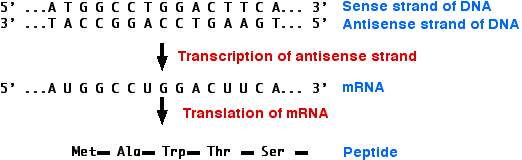

The majority of genes are expressed as the proteins they encode. The process occurs in two steps:

- Transcription = DNA → RNA

- Translation = RNA → protein

Gene Transcription: DNA → RNA

DNA serves as the template for the synthesis of RNA much as it does for its own replication.

The Steps of Transcription

- Some 50 different protein transcription factors bind to promoter sites, usually on the 5′ side of the gene to be transcribed.

- An enzyme, an RNA polymerase, binds to the complex of transcription factors.

- Working together, they open the DNA double helix.

- The RNA polymerase proceeds to read one strand moving in it's 3'→ 5' direction.

- In eukaryotes, this requires — at least for protein-encoding genes — that the nucleosomes in front of the advancing RNA polymerase (Pol II) be removed. A complex of proteins is responsible for this. The same complex replaces the nucleosomes after the DNA has been transcribed and Pol II has moved on.

- As the RNA polymerase travels along the DNA strand, it assembles ribonucleotides (supplied as triphosphates, e.g., ATP) into a strand of RNA.

- Each ribonucleotide is inserted into the growing RNA strand following the rules of base pairing. Thus for each C encountered on the DNA strand, a G is inserted in the RNA; for each G, a C; and for each T, an A. However, each A on the DNA guides the insertion of the pyrimidine uracil (U, from uridine triphosphate, UTP). There is no T in RNA.

- Synthesis of the RNA proceeds in the 5′ → 3′ direction.

- As each nucleoside triphosphate is brought in to add to the 3′ end of the growing strand, the two terminal phosphates are removed.

- When transcription is complete, the transcript is released from the polymerase and, shortly thereafter, the polymerase is released from the DNA.

Note that at any place in a DNA molecule, either strand may be serving as the template; that is, some genes "run" one way, some the other (and in a few remarkable cases, the same segment of double helix contains genetic information on both strands!). In all cases, however, RNA polymerase transcribes the DNA strand in its 3'→ 5' direction.

Types of RNA

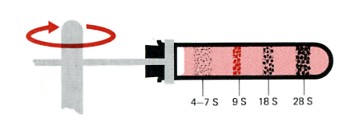

Sedimentation pattern produced by high-speed centrifugation of RNA extracted from the precursors of rabbit red blood cells. The discrete bands represent particular classes of RNA. The transfer RNAs band at about 4S. The ribosomal RNAs of eukaryotes sediment at 5S, 5.8S, 18S, and 28S. (The larger the sedimentation unit, S, the larger the molecule — but not proportionally.) The RNA forming the band at 9S is the messenger RNA for the synthesis of hemoglobin, the major protein synthesized in these cells. In most types of cells, the messenger RNAs are extremely heterogenous, with small amounts distributed from 6S to 25S.

Several types of RNA are synthesized in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells.

- messenger RNA (mRNA)

- ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

- transfer RNA (tRNA)

- small nuclear RNA (snRNA)

- small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA)

- microRNA (miRNA). These are tiny (~22 nucleotides) RNA molecules that regulate the expression of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules.

- long non-coding RNA (lncRNA)

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

Messenger RNA will be translated into a polypeptide. Messenger RNA comes in a wide range of sizes reflecting the size of the polypeptide it encodes. Most cells produce small amounts of thousands of different mRNA molecules, each to be translated into a peptide needed by the cell. Many mRNAs are common to most cells, encoding "housekeeping" proteins needed by all cells (e.g., the enzymes of glycolysis). Other mRNAs are specific for only certain types of cells. These encode proteins needed for the function of that particular cell (e.g., the mRNA for hemoglobin in the precursors of red blood cells).

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

This will be used in the building of ribosomes: machinery for synthesizing proteins by translating mRNA. There are 4 kinds. In eukaryotes, these are

- 18S rRNA. One of these molecules, along with some 30 different protein molecules, is used to make the small subunit of the ribosome.

- 28S, 5.8S, and 5S rRNA. One each of these molecules, along with some 45 different proteins, are used to make the large subunit of the ribosome.

The S number given each type of rRNA reflects the rate at which the molecules sediment in the ultracentrifuge. The larger the number, the larger the molecule (but not proportionally). The 28S, 18S, and 5.8S molecules are produced by the processing of a single primary transcript from a cluster of identical copies of a single gene. The 5S molecules are produced from a different cluster of identical genes.

Transfer RNA (tRNA)

These are the RNA molecules that carry amino acids to the growing polypeptide. There are some 32 different kinds of tRNA in a typical eukaryotic cell.

- Each is the product of a separate gene.

- They are small (~4S), containing 73-93 nucleotides.

- Many of the bases in the chain pair with each other forming sections of double helix.

- The unpaired regions form 3 loops.

- Each kind of tRNA carries (at its 3′ end) one of the 20 amino acids (thus most amino acids have more than one tRNA responsible for them).

- At one loop, 3 unpaired bases form an anticodon.

- Base pairing between the anticodon and the complementary codon on a mRNA molecule brings the correct amino acid into the growing polypeptide chain.

Small Nuclear RNA (snRNA)

DNA transcription of the genes for mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA produces large precursor molecules ("primary transcripts") that must be processed within the nucleus to produce the functional molecules for export to the cytosol. Some of these processing steps are mediated by snRNAs.

Approximately a dozen different genes for snRNAs, each present in multiple copies, have been identified. The snRNAs have various roles in the processing of the other classes of RNA. For example, several snRNAs are part of the spliceosomes that participate in converting pre-mRNA into mRNA by excising the introns and splicing the exons.

Small Nucleolar RNA (snoRNA)

As the name suggests, these small (60–300 nucleotides) RNAs are found in the nucleolus where they are responsible for several functions:

- Some participate in making ribosomes by helping to cut up the large RNA precursor of the 28S, 18S, and 5.8S molecules.

- Others chemically modify many of the nucleotides in rRNA, tRNA, and snRNA molecules, e.g., by adding methyl groups to ribose.

- Some have been implicated in the alternative splicing of pre-mRNA to different forms of mature mRNA.

- One snoRNA serves as the template for the synthesis of telomeres.

In vertebrates, the snoRNAs are made from introns removed during RNA processing.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

MicroRNAs" ("miRNAs") are single-stranded RNA molecules containing about 22 nucleotides and are about the same size as siRNAs. MicroRNAs are found in all animals (humans generate some 1000 miRNAs) and plants but not in fungi. They contain 19–25 nucleotide. They are

- encoded in the genome

- some by stand-alone genes (that may encode several miRNAs)

- some by portions of an intron of the gene whose mRNA they will regulate.

- may be expressed in

- only certain cell types and

- at only certain times in the differentiation of a particular cell type.

While direct evidence of the function of many of these newly-discovered gene products remains to be discovered, they regulate gene expression by regulating messenger RNA (mRNA), either

- destroying the mRNA when the sequences match exactly (the usual situation in plants) or

- repressing its translation when the sequences are only a partial match.

MicroRNAs have two traits ideally suited for this:

- Being so small, they can be rapidly transcribed from their genes.

- They do not need to be translated into a protein product to act.

MicroRNAs regulate (repress) expression of genes in mammals as well. Genome analysis has revealed thousands of human genes whose transcripts (mRNAs) contain sequences to which one or more of our miRNAs might bind. Probably each miRNA can bind to as many as 200 different mRNA targets while each mRNA has binding sites for multiple miRNAs. Such a system provides many opportunities for coordinated mRNA translation

Long Non-coding RNA (lncRNA)

Only messenger RNA encodes polypeptides. All the other classes of RNA are thus called non-coding RNA. In addition to the rRNAs, snRNAs, and snoRNAs, there is a large (more than 10,000 in humans), heterogenous collection of transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that are classified as lncRNAs. The function, if any, of most of these remains to be discovered.

However, some lncRNAs have been found to participate in the regulation of such diverse activities as splicing, translation, imprinting, and transcription. Two examples:

- XIST RNA, which contains thousands of nucleotides, inactivates one of the two X chromosomes in female vertebrates.

- Some lncRNAs participate in bringing the enhancer and promoter regions of genes close together ("looping") to regulate gene transcription.

While much remains to be learned about their functions, taken together non-coding RNAs probably account for three-quarters of the transcription going on in the nucleus.

The RNA polymerases

The RNA polymerases are huge multi-subunit protein complexes. Three kinds are found in eukaryotes.

- RNA polymerase I (Pol I). It transcribes the rRNA genes for the precursor of the 28S, 18S, and 5.8S molecules (and is the busiest of the RNA polymerases).

- RNA polymerase II (Pol II; also known as RNAP II). It transcribes protein-encoding genes into mRNA (and also the snRNA genes).

- RNA polymerase III (Pol III). It transcribes the 5S rRNA genes and all the tRNA genes.

RNA Processing: pre-mRNA → mRNA

All the primary transcripts produced in the nucleus must undergo processing steps to produce functional RNA molecules for export to the cytosol. We shall confine ourselves to a view of the steps as they occur in the processing of pre-mRNA to mRNA.

Most eukaryotic genes are split into segments. In decoding the open reading frame of a gene for a known protein, one usually encounters periodic stretches of DNA calling for amino acids that do not occur in the actual protein product of that gene. Such stretches of DNA, which get transcribed into RNA but not translated into protein, are called introns. Those stretches of DNA that do code for amino acids in the protein are called exons. Examples:

- The gene for one type of collagen found in chickens is split into 52 separate exons.

- The gene for dystrophin, which is mutated in boys with muscular dystrophy, has 79 exons.

- Even the genes for rRNA and tRNA are split by introns.

- The human genome is estimated to contain some 180,000 exons. With a current estimate of 21,000 genes, the average exon content of our genes is about 9.

- Synthesis of the cap. This is a modified guanine (G) which is attached to the 5′ end of the pre-mRNA as it emerges from RNA polymerase II (Pol II). The cap

- protects the RNA from being degraded by enzymes that degrade RNA from the 5′ end;

- serves as an assembly point for the proteins needed to recruit the small subunit of the ribosome to begin translation.

- Step-by-step removal of introns present in the pre-mRNA and splicing of the remaining exons. This step takes place as the pre-mRNA continues to emerge from Pol II.

- Synthesis of the poly(A) tail. This is a stretch of adenine (A) nucleotides. When a special poly(A) attachment site in the pre-mRNA emerges from Pol II, the transcript is cut there, and the poly(A) tail is attached to the exposed 3′ end. This completes the mRNA molecule, which is now ready for export to the cytosol. (The remainder of the transcript is degraded, and the RNA polymerase leaves the DNA.)

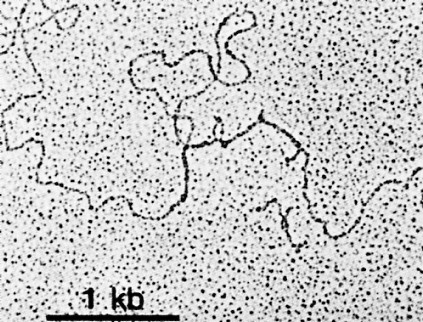

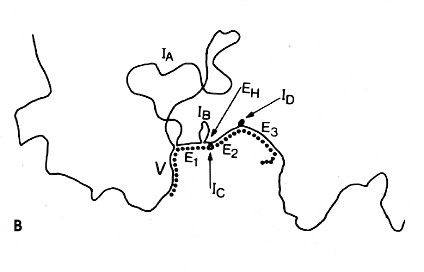

The above image is an electron micrograph of a mRNA-DNA hybrid molecule formed by mixing the messenger RNA (mRNA) from a clone of antibody-secreting cells with single-stranded DNA from the same kind of cells. The bar represents the length of 1000 bases. The lower diagram is an interpretation of the micrograph. The solid line represents the DNA; the dotted line the mRNA. The loops (IA, IB, etc.) represent the introns that separate the exons encoding the domains of an antibody heavy chain:

- V = variable region

- E1 = first constant region (CH1) domain

- EH = hinge region

- E2 and E3 = the nucleotides encoding the two C-terminal domains (CH2 and CH3)

The unhybridized portion of the mRNA is its poly(A) tail.

Alternative Splicing

The processing of pre-mRNA for many proteins proceeds along various paths in different cells or under different conditions. For example, early in the differentiation of a B cell (a lymphocyte that synthesizes an antibody) the cell first uses an exon that encodes a transmembrane domain that causes the molecule to be retained at the cell surface. Later, the B cell switches to using a different exon whose domain enables the protein to be secreted from the cell as a circulating antibody molecule.

Alternative splicing provides a mechanism for producing a wide variety of proteins from a small number of genes. While we humans may turn out to have only some 20 thousand genes, we probably make at least 10 times that number of different proteins. It is now estimated that 92–94% of our genes produce pre-mRNAs that are alternatively-spliced. There is evidence that the pattern of alternative splicing differs consistently in different tissues and so must be regulated. But whether all the products are functional or that many are simply the outcome of an error-prone process remains to be seen.

Alternative splicing not only provides different proteins from a single gene but also different 3' UTRs and 5' UTRs. Although not translated into protein, these untranslated regions contain signals that, for example, dictate where in the cell that protein will accumulate. Two examples:

- The 3' UTR of the bicoid gene in Drosophila directs the mRNA to the anterior of the embryo

- the same region in the VegT gene of Xenopus directs its mRNA to the vegetal pole of the embryo

One of the most dramatic examples of alternative splicing is the Dscam gene in Drosophila. This single gene contains some 116 exons of which 17 are retained in the final mRNA. Some exons are always included; others are selected from an array. Theoretically this system is able to produce 38,016 different proteins. And, in fact, over 18,000 different ones have been found in Drosophila hemolymph.

These Dscam proteins are used to establish a unique identity for each neuron. It works like this. Each developing neuron synthesizes a dozen or so Dscam mRNAs out of the thousands of possibilities. Which ones are selected appears to be simply a matter of chance, but because of the great number of possibilities, each neuron will most likely end up with a unique set of a dozen or so Dscam proteins. As each developing neuron in the central nervous system sprouts dendrites and an axon, these express its unique collection of Dscam proteins. If the various extensions of a single neuron should meet each other in the tangled web that is the hallmark of nervous tissue, they are repelled. In this way, thousands of different neurons can coexist in intimate contact without the danger of nonfunctional contacts between the various extensions of the same neuron.

Whether a particular segment of RNA will be retained as an exon or excised as an intron can vary under different circumstances, such as

- what type of cell the gene is in

- what stage of differentiation that cell is passing through

- what extracellular signals that cell is receiving.

Clearly the switching to an alternate splicing pathway must be closely regulated.

Trans-splicing

Most genes are transcribed and their transcripts processed as described above. RNA polymerase travels down a single strand of a single gene locus to form pre-mRNA that is processed (including removal of introns) to form the mature mRNA. But there are exceptions. A number of cases have been found where two different precursor transcripts have been spliced together to form the final RNA molecule. The phenomenon is called trans-splicing.

Examples: synthesis of a single RNA molecule by splicing together transcripts from loci

- located far apart on the same chromosome or

- on opposite strands of the same gene locus or

- that are the two alleles of the gene on their separate (homologous) chromosomes.

The biological importance of these trans-spliced transcripts is still unknown for most of them.