2.5: Non-Mendelian inheritance review

- Page ID

- 73734

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Key terms

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Incomplete dominance | Pattern of heredity in which one allele is not completely dominant over another |

| Codominance | Pattern of heredity in which both alleles are simultaneously expressed in the heterozygote |

| Multiple alleles | A gene that is controlled by more than two alleles |

| Pleiotropy | When one gene affects multiple characteristics |

| Lethal allele | Allele that results in the death of an individual |

| Polygenic trait | Traits that are controlled by multiple genes |

Variations involving single genes

Some of the variations on Mendel’s rules involve single genes.

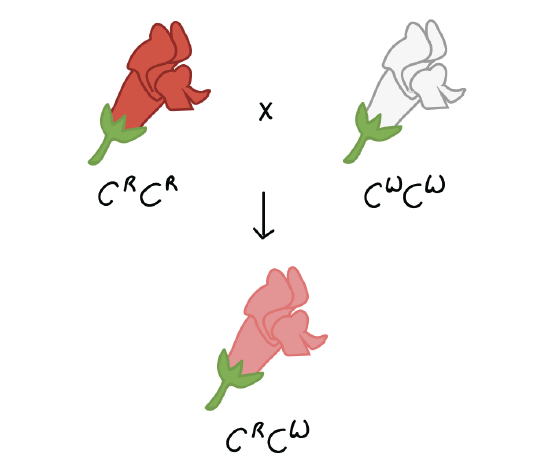

- Incomplete dominance. Two alleles may produce an intermediate phenotype when both are present, rather than one fully determining the phenotype.

An example of this is the snapdragon plant. A cross between a homozygous white-flowered plant (\(C^WC^W\)) and a homozygous red-flowered plant (\(C^RC^R\)) will produce offspring with pink flowers (\(C^RC^W\)).

-

Codominance. Two alleles may be simultaneously expressed when both are present, rather than one fully determining the phenotype.

Codominance in erminette chicken. Image from Wikimedia, CC BY 2.0. In some varieties of chickens, the allele for black feathers is codominant with the allele for white feathers. A cross between a black chicken and a white chicken will result in a chicken with both black and white feathers.

-

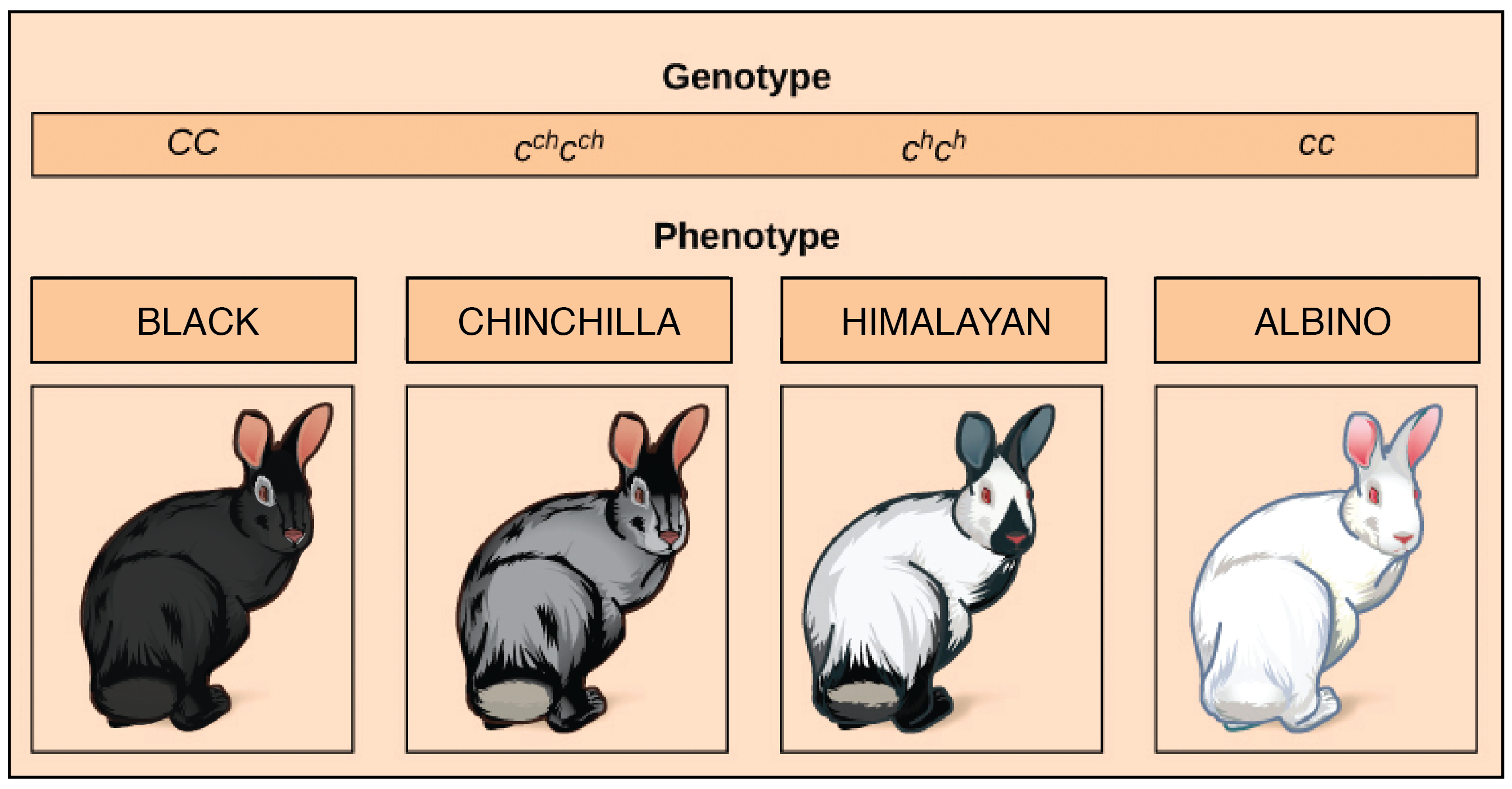

Multiple alleles. Mendel studied just two alleles of his pea genes, but real populations often have multiple alleles of a given gene.

Image from OpenStax, CC BY 3.0 An example of this is the gene for coat color in rabbits (the \(C\) gene) which comes in four common alleles: \(C\), \(c^{ch}\), \(c^h\), and \(c\).

-

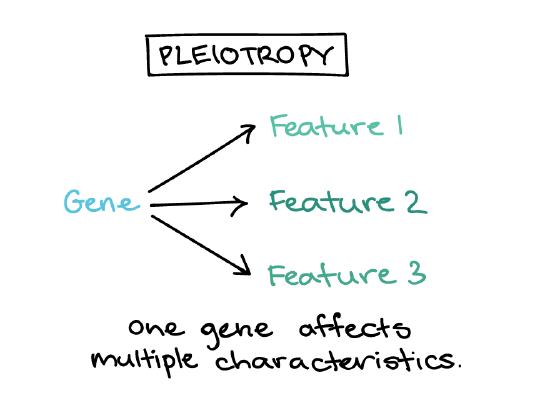

Pleiotropy. Some genes affect many different characteristics, not just a single characteristic.

Based on similar diagram by Ingrid Lobo1. An example of this is Marfan syndrome, which results in several symptoms (unusually tall height, thin fingers and toes, lens dislocation, and heart problems). These symptoms don’t seem directly related, but as it turns out, they can all be traced back to the mutation of a single gene.

-

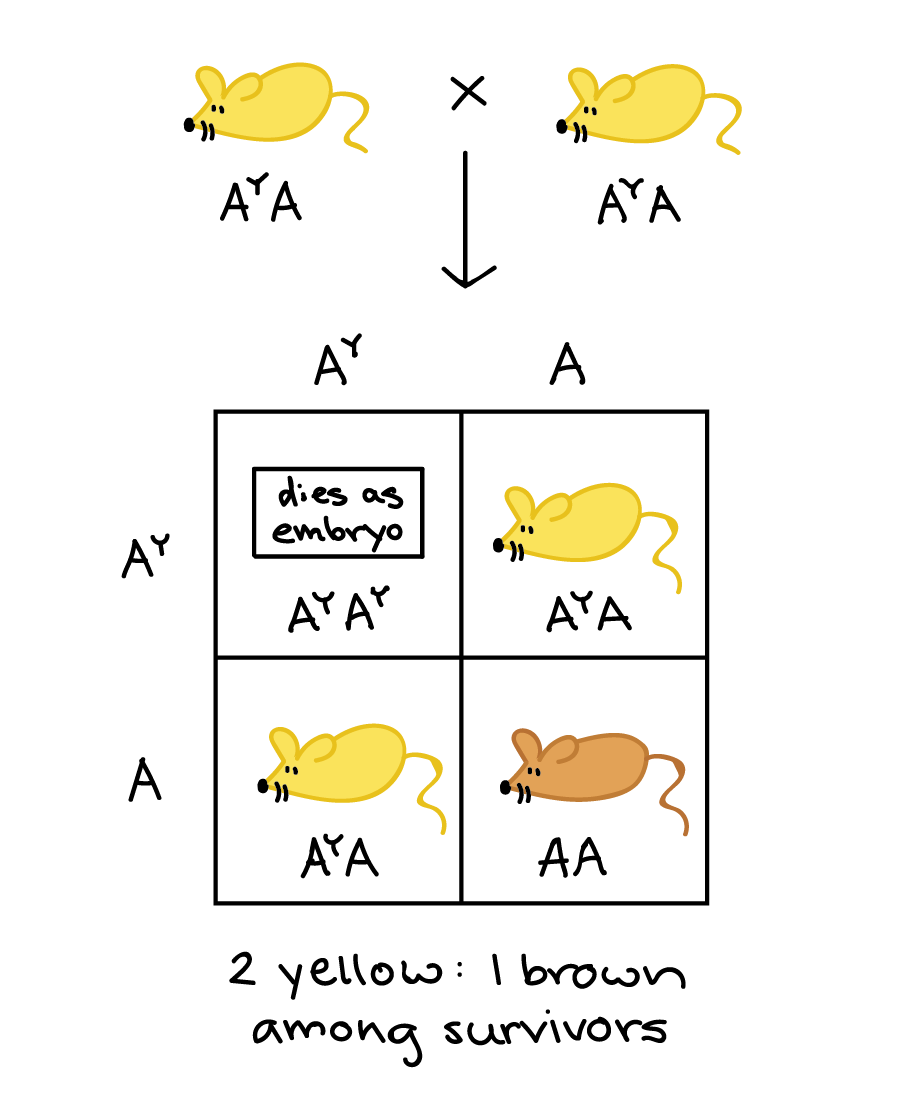

Lethal alleles. Some genes have alleles that prevent survival when homozygous or heterozygous.

A classic example of an allele that affects survival is the lethal yellow allele, a spontaneous mutation in mice that makes their coats yellow. Mice that are homozygous (\(A^YA^Y\)) genotype die early in development. Although this particular allele is dominant, lethal alleles can be dominant or recessive, and can be expressed in homozygous or heterozygous conditions.

Polygenic inheritance and environmental effects

Many characteristics, such as height, skin color, eye color, and risk of diseases, are controlled by many factors. These factors may be genetic, environmental, or both.

-

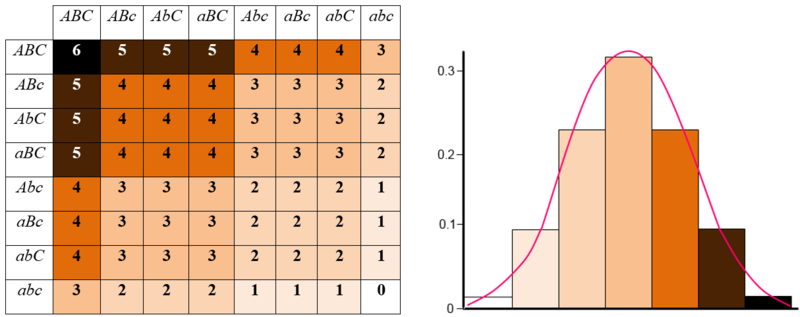

Polygenic inheritance. Some characteristics are polygenic, meaning that they’re controlled by a number of different genes. In polygenic inheritance, traits often form a phenotypic spectrum rather than falling into clear-cut categories.

Human skin color chart. Image from Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0. An example of this is skin pigmentation in humans, which is controlled by several different genes.

-

Environmental effects. Most real-world characteristics are determined not just by genotype, but also by environmental factors that influence how genotype is translated into phenotype.

Blue and pink hydrangea due to variance in soil pH. Image by Lynn Greyling, Public domain An example of this is the hydrangea flower. Hydrangea of the same genetic variety may vary in color from blue to pink depending on the pH of the soil they are in.

Common mistakes and misconceptions

- Some people confuse pleiotropy and polygenic inheritance. The major difference between the two is that pleiotropy is when one gene affects multiple characteristics (e.g. Marfan syndrome) and polygenic inheritance is when one trait is controlled by multiple genes (e.g. skin pigmentation).

- Codominance and incomplete dominance are not the same. In codominance, neither allele is dominant over the other, so both will be expressed equally in the heterozygote. In incomplete dominance, there is an intermediate heterozygote (such as a pink flower when the parents' phenotypes are red and white).

Contributors and Attributions

Khan Academy (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; All Khan Academy content is available for free at www.khanacademy.org)