2.3: Pleiotropy and lethal alleles

- Page ID

- 73732

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

From Mendel’s experiments, you might imagine that all genes control a single characteristic and affect some harmless aspect of an organism’s appearance (such as color, height, or shape). Those predictions are true for some genes, but definitely not all of them! For example:

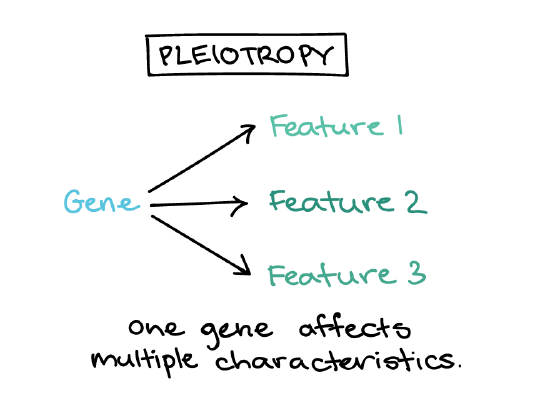

- A human genetic disorder called Marfan syndrome is caused by a mutation in one gene, yet it affects many aspects of growth and development, including height, vision, and heart function. This is an example of pleiotropy, or one gene affecting multiple characteristics.

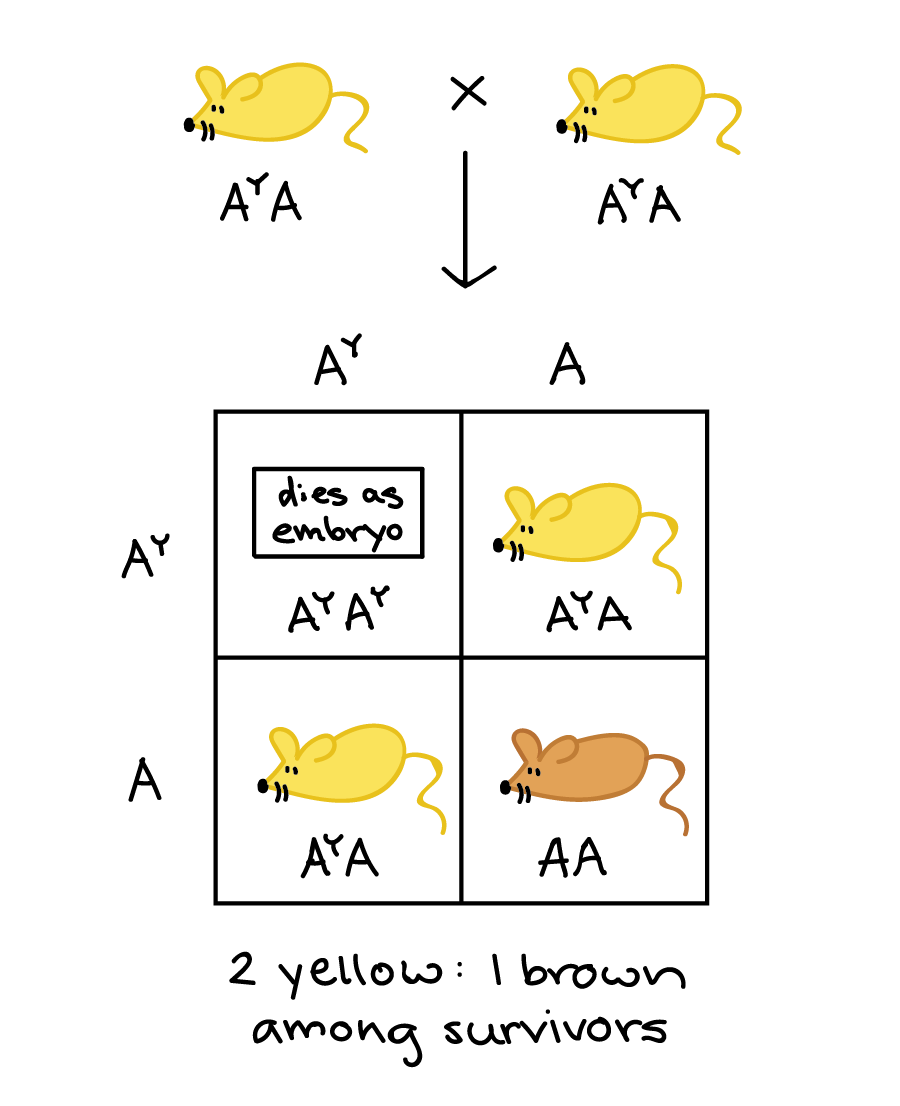

- A cross between two heterozygous yellow mice produces yellow and brown mice in a ratio of 2:1, not 3:1. This is an example of lethality, in which a particular genotype makes an organism unable to survive.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at pleiotropic genes and lethal alleles, seeing how these variations on Mendel's rules fit into our modern understanding of inheritance.

Pleiotropy

When we mentioned Mendel’s experiments with purple-flowered and white-flowered plants, we didn’t discuss any other phenotypes associated with the two flower colors. However, Mendel noticed that the flower colors were always correlated with two other features: the color of the seed coat (covering of the seed) and the color of the axils (junctions where the leaves met the stem)1,2.

In plants with white flowers, the seed coats and axils were colorless. In plants with purple flowers, on the other hand, the seed coats were brown-gray and the axils were reddish. Thus, rather than affecting just one characteristic, the flower color gene actually affected three.

Genes like this, which control multiple, seemingly unrelated features, are said to be pleiotropic (pleio- = many, -tropic = effects)1. We now know that Mendel’s flower color gene specifies a protein that causes colored particles, or pigments, to be made2. This protein works in several different parts of the pea plant (flowers, seed coat, and leaf axils). In this way, the seemingly unrelated phenotypes can be traced back to a defect in one gene with several jobs.

Importantly, alleles of pleiotropic genes are transmitted in the same way as alleles of genes that affect single traits. Although the phenotype has multiple elements, these elements are specified as a package, and the dominant and recessive versions of the package would appear in the offspring of two heterozygotes in a ratio of 3:1.

Pleiotropy in human genetic disorders

Genes affected in human genetic disorders are often pleiotropic. For example, people with a hereditary disorder called Marfan syndrome may have a set of seemingly unrelated symptoms, including the following1,3:

- Unusually tall height

- Thin fingers and toes

- Dislocation of the lens of the eye

- Heart problems (in which the aorta, the large blood vessel carrying blood away from the heart, bulges or ruptures).

These symptoms don’t seem directly related, but as it turns out, they can all be traced back to the mutation of a single gene. This gene encodes a protein that assembles into chains, making elastic fibrils that give strength and flexibility to the body’s connective tissues4. Mutations that cause Marfan syndrome reduce the amount of functional protein made by the body, resulting in fewer fibrils.

How does the identity of this gene explain the range of symptoms? Our eyes and the aortas normally contain many fibrils that help maintain structure, which is why these two organs are affected in Marfan syndrome5. In addition, the fibrils serve as “storage shelves” for growth factors. When there are fewer of them in Marfan syndrome, the growth factors cannot be shelved and thus cause excess growth (leading to the characteristic tall, thin Marfan build)4.

Lethality

For the alleles that Mendel studied, it was equally possible to get homozygous dominant, homozygous recessive, and heterozygous genotypes. That is, none of these genotypes affected the survival of the pea plants. However, this is not the case for all genes and all alleles.

Many genes in an organism’s genome are needed for survival. If an allele makes one of these genes nonfunctional, or causes it to take on an abnormal, harmful activity, it may be impossible to get a living organism with a homozygous (or, in some cases, even a heterozygous) genotype.

Example: The yellow mouse

A classic example of an allele that affects survival is the lethal yellow allele, a spontaneous mutation in mice that makes their coats yellow. This allele was discovered around the turn of the 20th century by the French geneticist Lucien Cuenót, who noticed that it was inherited in an unusual pattern6,7.

When yellow mice were crossed with normal agouti (brown) mice, they produced half yellow and half brown offspring. This suggested that the yellow mice were heterozygous, and that the yellow allele, \(A^Y\), was dominant to the agouti allele, \(A\). But when two yellow mice were crossed with each other, they produced yellow and brown offspring in a ratio of 2:1, and the yellow offspring did not breed true (were heterozygous). Why was this the case?

As it turned out, this unusual ratio reflected that some of the mouse embryos (homozygous \(A^YA^Y\) genotype) died very early in development, long before birth. In other words, at the level of eggs, sperm, and fertilization, the color gene segregated normally, resulting in embryos with a 1:2:1 ratio of \(A^YA^Y\), \(A^YA\), and \(AA\) genotypes. However, the \(A^YA^Y\) mice died as tiny embryos, leaving a 2:1 genotype and phenotype ratio among the surviving mice7,8.

Alleles like \(A^Y\), which are lethal when they're homozygous but not when they're heterozygous, are called recessive lethal alleles.

- [Wait, isn't yellow color dominant?]

-

The lethal recessive \(A^Y\) allele also happens to give a dominant, non-lethal phenotype in the heterozygote (yellow coloration, along with health problems such as obesity, diabetes, and tumor formation). The trick is that the lethality is recessive, even though the color phenotype is dominant.

The color of the yellow mouse heterozygote is helpful because it lets us keep track of genotypes, but in many other cases, recessive lethal genes don’t have a dominant phenotype in the heterozygote. Instead, they are purely recessive to the normal allele, resulting in a normal phenotype for the heterozygote and an embryonic lethal phenotype for the homozygote.

Lethal alleles and human genetic disorders

Some alleles associated with human genetic disorders are recessive lethal. For example, this is true of the allele that causes achondroplasia, a form of dwarfism. A person heterozygous for this allele will have shortened limbs and short stature (achondroplasia), a condition that is not lethal. However, homozygosity for the same allele causes death during embryonic development or the first months of life, an example of recessive lethality7,9.

Some human disorders are also caused by dominant lethal alleles. These are alleles that cause death when they are present in just a single copy. If an allele leads to death of heterozygotes before birth, we’ll never see that allele in the living human population (but rather, as an implantation failure or miscarriage). However, if a dominant lethal allele allows heterozygotes to survive past birth, it can be seen in the population as a genetic disorder.

In fact, if a dominant lethal allele lets a person survive to reproductive age, it may even be passed on to children. This is the case in Huntington’s disease, a fatal genetic disorder affecting the nervous system. People with a Huntington allele inevitably develop the disease, but they may not show any symptoms until age 40 and can unknowingly pass the allele on to their children.

Contributors and Attributions

Khan Academy (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0; All Khan Academy content is available for free at www.khanacademy.org)

- [Attribution and references]

-

Attribution:

This article is a modified derivative of “Characteristics and traits,” by OpenStax College, Biology (CC BY 3.0). Download the original article for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@9.85.

The modified article is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Works cited:

-

Lobo, I. (2008). Pleiotropy: One gene can affect multiple traits. Nature Education, 1(1), 10. Retrieved from www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/pleiotropy-one-gene-can-affect-multiple-traits-569.

-

Reid, J. B. and Ross, J. J. (2011). Mendel's genes: Towards a full molecular characterization. Genetics 189(1), 3-10. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3176118/#s4title.

-

Marfan syndrome. (2012). In Genetics home reference. Retrieved from http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/marfan-syndrome.

-

FBN1. (2015). In Genetics home reference. Retrieved from http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/FBN1.

-

Marfan syndrome. (2015, November 3). Retrieved November 21, 2015 from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marfan_syndrome.

-

Lethal allele. (2016, July 13). Retrieved July 26, 2016 from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lethal_allele#History.

-

Lobo, I. (2008). Mendelian ratios and lethal genes. Nature Education, 1(1), 138. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/mendelian-ratios-and-lethal-genes-557.

-

Griffiths, A. J. F., Gelbart, W. M., Miller, J. H., and Lewontin, R. C. (1999). Interactions between alleles of one gene. In Modern Genetic Analysis. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21226/#_A824_.

-

Achrondroplasia. (2015, September 12). Retrieved November 21, 2015 from WIkipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achondroplasia.

Additional references:

Achrondroplasia. (2015, September 12). Retrieved November 21, 2015 from WIkipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achondroplasia.

Bergmann, D. C. (2011). Genetics lecture notes. Biosci 41, Stanford.

FBN1. (2015). In Genetics home reference. Retrieved from http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/FBN1.

Griffiths, A. J. F., Gelbart, W. M., Miller, J. H., and Lewontin, R. C. (1999). Interactions between alleles of one gene. In Modern Genetic Analysis. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21226.

Lethal allele. (2015). In The free dictionary. Retrieved from http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/lethal+allele.

Lethal allele. (2016, July 13). Retrieved July 26, 2016 from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lethal_allele.

Lobo, I. (2008). Mendelian ratios and lethal genes. Nature Education, 1(1), 138. Retrieved from http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/mendelian-ratios-and-lethal-genes-557.

Lobo, I. (2008). Pleiotropy: One gene can affect multiple traits. Nature Education, 1(1), 10. Retrieved from www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/pleiotropy-one-gene-can-affect-multiple-traits-569.

Lucien Cuénot. (2016, February 13). Retrieved July 26, 2016 from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucien_Cuénot.

Marfan syndrome. (2012). In Genetics home reference. Retrieved from http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/marfan-syndrome.

Reece, J. B., Urry, L. A., Cain, M. L., Wasserman, S. A., Minorsky, P. V., and Jackson, R. B. (2011). Mendel and the gene idea. In Campbell biology (10th ed., pp. 267-291). San Francisco, CA: Pearson.

Reid, J. B. and Ross, J. J. (2011). Mendel's genes: Towards a full molecular characterization. Genetics 189(1), 3-10. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3176118/

-