1.1: Assessing Slope of the Land

- Page ID

- 20243

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Here in the Pacific Northwest, we are fortunate to work in a landscape of varied landforms – from volcanic peaks to wide valleys; from steep, forested hillsides to gently rolling savannas; from rapidly cascading mountain streams to meandering river floodplains. Our varied topography is an integral part of our forest ecosystems, influencing our climate, soils, water, plant life and fish habitat (Figure 1.1). As natural resource technicians, we are often called upon to assess the topography, and one of the common elements we measure is the slope of the land. How steep is the hillside? Does the slope drain to a stream? Are there cliffs or bluffs present? Field data collected by technicians lead to informed decisions about land management activities such as providing shade for streams, building roads or trails, and prescribing timber management operations.

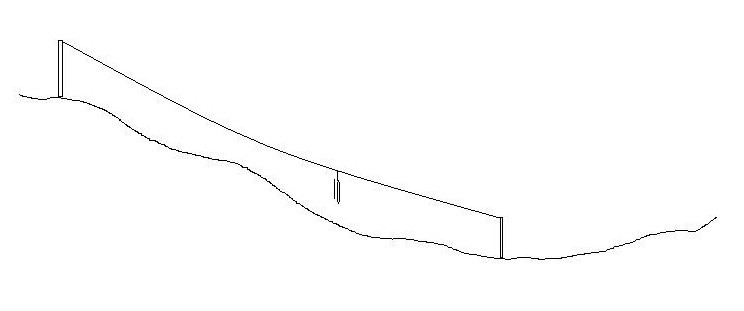

Figure 1.1. The Muddy Fork of the Sandy River originates from snowfields on the west flank of Mt. Hood, carrying coarse gravels and sand downstream. Fine soils from the surrounding steep, forested slopes also make their way down the slope to the river.

Defining Slope

Slope of the land is essentially the gradient or incline of the land. A steep slope refers to a sharp incline; a gentle slope refers to a slight incline. The steep, forested slopes in Figure 1.1 contrast with the gentler slope of the river’s path as it flows between them.

Driving down a highway you may see a road sign that reads “6% Grade” or “steep grade.” The grade of the road is essentially the slope of the road. The sign in Figure 1.2 indicates that the road descends at a 6% grade or a 6% slope.

Figure 1.2. A road sign indicating an 8% grade, or 8% slope. (www.dot.state.co.us)

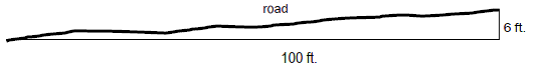

A 6% slope means that the road elevation changes 6 feet for every 100 feet of horizontal distance (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. A road climbs at a gradient of 6%. The road gains 6 feet in elevation for every 100 feet of horizontal distance. Note that the length of the road itself is longer than 100 feet.

Mathematically, slope is defined as “the rise over the run” (or the rise divided by the run), where rise equals change in elevation and run equals horizontal distance:

or

or  or in this case:

or in this case:

To express slope as a percent slope, we simply multiply the slope fraction by 100. So, .06 = 6%

%slope

%slope

6%

6%

In our road example, the six foot change in elevation is the rise and the 100 foot horizontal distance of the road is the run. Driving uphill, we climb a +6% slope (Figure A below). Driving downhill, the “rise” is actually a “drop,” so we have a negative slope, or a downhill slope (Figure B below). When dealing with slope, a positive slope simply means uphill and a negative slope means downhill. A negative number does not mean “minus” as in algebraic expressions.

Note that the actual road distance is the hypotenuse of the illustrated slope triangle. Its length is called slope distance. Slope distance is always longer than the horizontal distance, or run. Applying the Pythagorean Theorem (a2 + b2 = c2) to this triangle, we can calculate the slope distance, or hypotenuse (c).

a2 + b2 = c2 where: 1002 + 62 = c2 10,036 = c2  ft.

ft.

a = horizontal distance or run (in this example 100 ft.)

b= change in elevation or rise (in this example 6 ft.)

c = road distance or slope distance (in this example 100.2 ft.)

We calculated a slope distance of 100.2 ft. for a run of 100 ft. As you can see from this example, in a forest, a 6% slope would be considered a gentle slope.

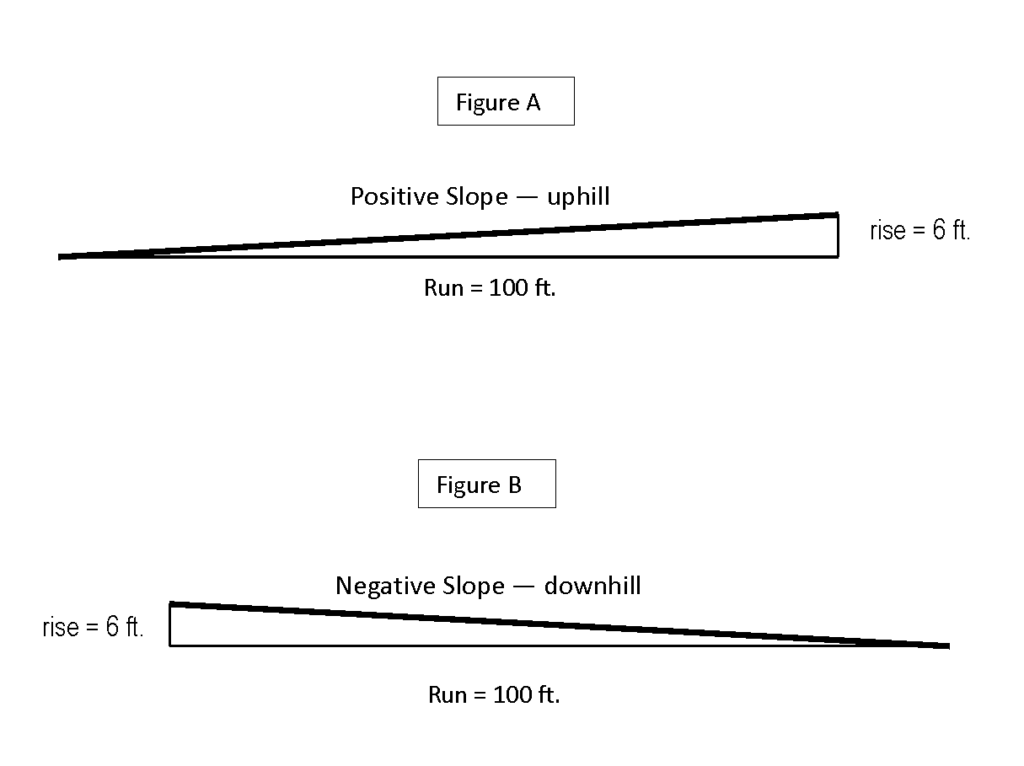

Note that %slope is unitless and proportional. Therefore, it can be applied to any unit of measure (inches, yards, centimeters, etc.) and to any length. For example, a 25% slope is simply a 25:100 ratio. The 25% slope below shows that for every inch of horizontal distance, the slope rises .25 inches. For every 10 centimeters of horizontal distance, the slope rises 2.5 cm, and for every 5 inches of horizontal distance, it rises 1.25 inches.

Using Slope

When writing field notes about a site, we include information about the slope of the land. Sometimes a rough estimate of the average slope is sufficient; sometimes detailed measurements of slope are required. For example, a site description might read:

“A timber cruise was conducted on 20 acres of mixed conifer forest …………Approximately half of the acreage was flat, on slopes ranging from 3-7%. The other half of the acreage was steeper; with southwest slopes 40-60%.”

This tells us much more about the site than simply stating that there were 20 acres of mixed forest. We would expect different soil conditions and different vegetation to be present on the different slopes, and therefore, perhaps different management. Let’s say, for example, that these 20 acres are to be logged in the near future. If this is so, the forester will have to plan where to place any new access roads, where to locate landings for yarding the logs and what type of harvesting equipment to use. He knows that the slope of any new spur roads should not exceed 10%, and a cable system should be used to haul logs up to landings on slopes greater than 30% (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. A cable logging system can be used on steep slopes to suspend logs above the ground as they “yard” the logs up the slope to a landing.

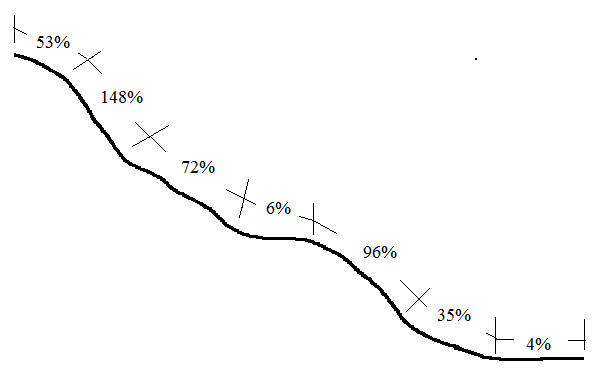

Profiles may be run to get a detailed picture of the slope. When profiling a hillside, slope distances and %slope readings are taken where each major change in slope occurs (Figure 1.5). With this precise information, a logging system can be designed that will lift logs off the ground while yarding to reduce erosion.

Figure 1.5. A hillside is divided into segments where major changes in slope occur. For each segment, a %slope reading is taken. These %readings are combined with measurements of the slope distance for each segment to create a profile or sketch of the hill like the one illustrated.

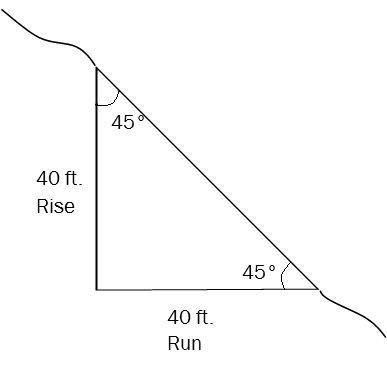

Note that slopes can exceed 100%. When a slope equals 100%, it simply means that the rise is equal to the run. And although it certainly feels like you are climbing straight up on a 100% slope (pulling yourself up using roots and anything else you can grab), you are really walking up at a 45° angle, not a 90° angle.

%slope

%slope

If rise = run as illustrated above:  100%

100%

100% slope = 45º angle slope

Other examples of where %slope is measured in natural resource settings include hiking trails and streams. Switchbacks on steep slopes reduce trail erosion and make hiking easier. Some trails are kept to 8% to comply with American with Disabilities Act (ADA) guidelines for wheelchair access.

Stream gradients vary, reflecting the terrain over which they flow at each stage of their journey to large rivers. Small tributaries often are the steepest, cascading down steep forested slopes at gradients of 60-100% slope or more. As streams merge downriver, the terrain often flattens out, and milder gradients of 3-10% slope may be measured (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Streams rush down steep slopes at their headwaters. As they reach valley bottoms and merge with other streams, their gradients are reduced and a more meandering route may result.