2.5.3.1: Lycopodiopsida

- Page ID

- 37012

Learning Objectives

- Describe the characteristics of lycophytes.

- Differentiate between homosporous and heterosporous strobili.

Lycopodiopsida, or lycophytes, have at least four genera and more than 1,200 species. Extant lycophytes (those species still alive today) are represented by creeping forms, such as Lycopodium and Selaginella. Prominent members of this group are often called club mosses. They are not mosses at all, but vascular plants with xylem and phloem running through their roots, stems, and leaves. The leaves are quite simple and small with their vascular tissue in a single, unbranched vein. The "club" of their name comes from the appearance of their spore-forming structures called strobili. Some lycophytes (clubmosses Huperzia and Lycopodium) have equal spores and underground gametophytes, whereas Selaginella (spikemoss) and Isoëtes (quillwort) are both heterosporous with reduced aboveground gametophytes. Quillwort is a direct descendant of giant Carboniferous lycophyte trees, and despite being an underwater hydrophyte, it still retains the unusual secondary thickening of stem. Many spike mosses are poikilohydric (another similarity with mosses).

Characteristics

- Microphylls. Leaves with a single, unbranched vein of vascular tissue. Microphylls may have evolved from enations, scale-like appendages that later gained vascular tissue. Another possibility is that microphylls evolved from sporangia. Note: The term microphyll, confusingly, is not an indication of the size of the leaf.

- Rhizomes. Asexual propogation of the sporophyte through underground stems.

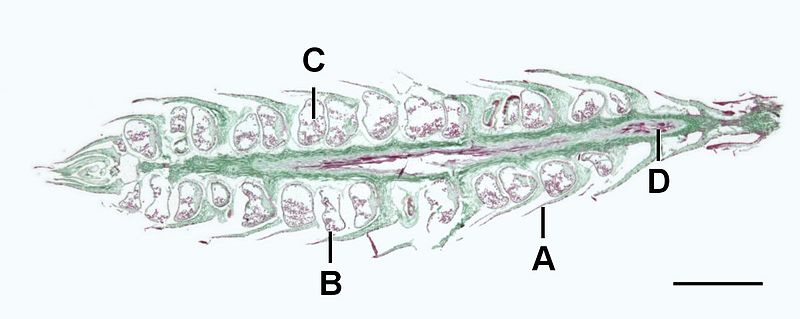

- Strobili. Cone-like structures where sporangia are produced on leaves called sporophylls (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

- Homosporous or heterosporous. Haploid spores grow into bisexual gametophytes in Lycopodium. In Selaginella, microspores develop into microgametophytes that produce sperm and megaspores develop into megagametophytes that produce eggs.

Lycopodium

Members of this genus are homosporous, meaning they produce spores that develop into bisexual gametophytes, producing both antheridia and archegonia on the same thallus.

Gametophyte Morphology

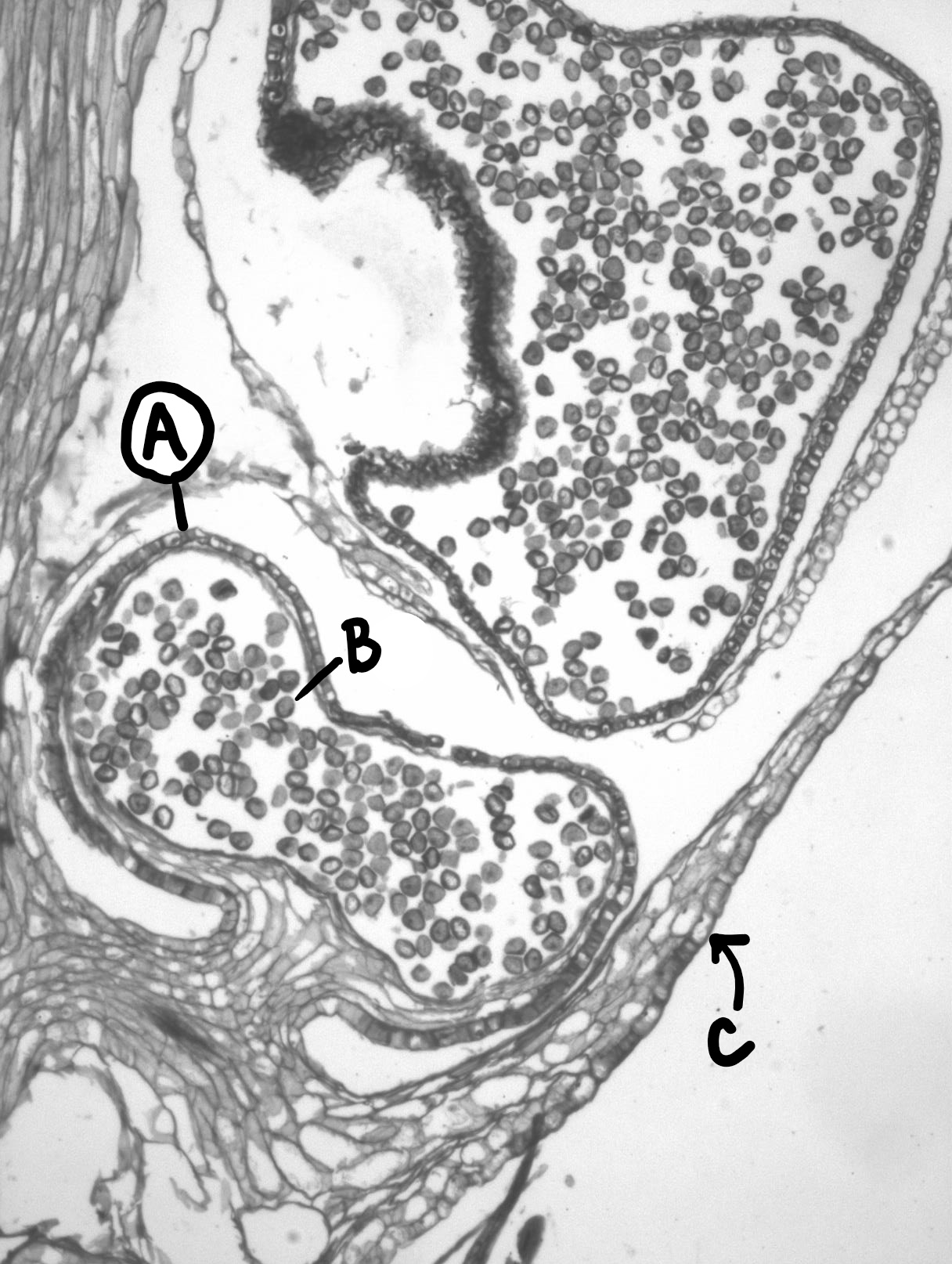

In seedless vascular plants, the sporophyte is the longer-lived, larger, leafy generation. This trend of sporophyte dominance throughout the evolutionary timeline of plants leads to continually smaller, less complex gametophytes. Gametophytes of this group are seldom seen. They are small and thalloid (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). In Lycopodium, the gametophyte grows from a homospore and is bisexual, producing both antheridia and archegonia.

Sporophyte Morphology

Sporophytes branch dichotomously and have true roots, stems, and leaves due to the presence of lignified vascular tissue. This lignified vascular tissue provides rigid structural support, allowing sporophytes to grow tall. The leaves, called microphylls, have a single, unbranched vein of vascular tissue (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Asexual propogation of sporophytes can occur via an underground stem that travels horizontally, called a rhizome.

To sexually reproduce, these plants produce cone-like structures at the end of their branches, called strobili. A strobilus is composed of leaves called sporophylls that bear sporangia (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Meiosis occurs within the sporangia to produce haploid homospores. Unlike the bryophytes, a single sporophyte can produce many sporangia (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

Selaginella

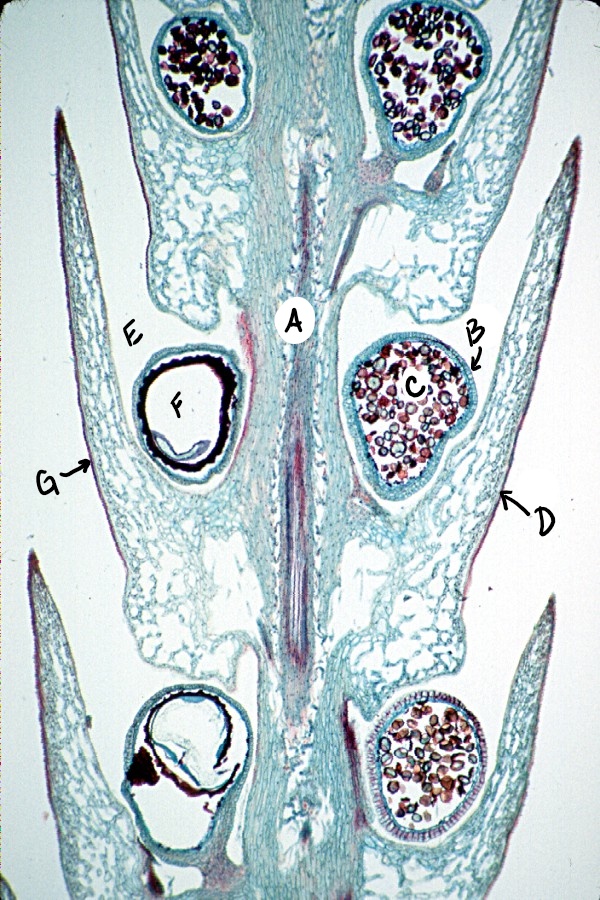

Members of the genus Selaginella are heterosporous, meaning they produce two different types of spores. Larger spores (megaspores) develop within megasporangia and are subtended by megasporophylls. Megaspores develop into gametophytes that produce archegonia. Smaller spores (microspores) develop within microsporangia and are subtended by microsporophylls. Microspores develop into gametophytes that produce antheridia. Megasporangia and microsporangia are found in the same strobilus (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\))

Extinct SVPs

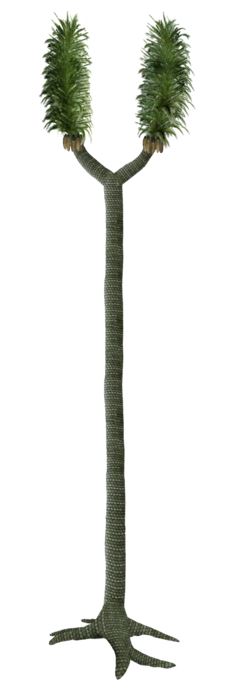

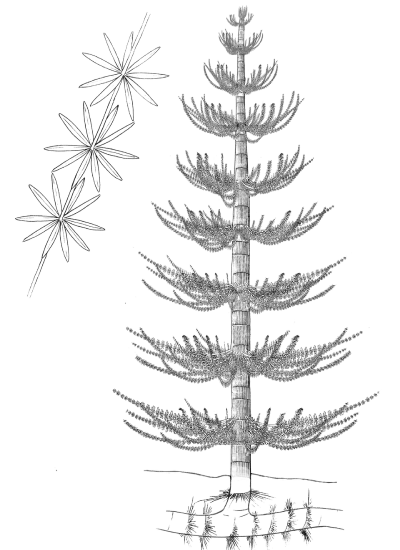

Extinct lycophytes like Lepidodendron and Sigillaria grew into tall trees, branching dichotomously and producing a moss-like canopy of microphylls over 100 feet (30 m) in the air (Figures \(\PageIndex{7-8}\)). Some of these microphylls were several feet long! Lycophytes first appear in the fossil record over 400 million years ago. By the Carboniferous period (around 300 mya), the landscape was covered with lycophyte forests and shallow swamps. Much of the fossil fuels we use today are derived from these extinct arboreal lycophytes falling into swamps, slowing decomposition and creating layers of carbon-rich material that we now find as coal seams.

An ancestor of modern-day Equisetum, Calamites, is thought to look much like the Equisetum species we see today, excepting that it would have been 60 feet (20 m) tall (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Most ancient pteridophytes appeared in Silurian period, they were rhyniophytes. Rhyniophyles had well-developed aboveground gametophytes and relatively short, dichotomously branched leafless sporophytes. The next important steps were formation of leaves and further reduction of gametophytes.

Attribution

- Curated and authored by Maria Morrow using 19.1.5 Diversity and Evolutionary Relationships of the Plants from Biology by John. W. Kimball (licensed CC-BY)

- Microphyll evolution added by Melissa Ha