10.2: Lipids Aggregates in Water - Micelles and Liposomes

- Page ID

- 14977

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)-

Describe the Behavior of Single-Chain Amphiphiles in Water:

• Explain how single-chain amphiphiles interact with water, including their ability to dissolve as monomers, form a surface monolayer, or self-aggregate into micelles when their concentration exceeds the critical micelle concentration (CMC). -

Explain Micelle Formation Mechanisms:

• Describe the noncovalent interactions (e.g., induced dipole-induced dipole forces, ion-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonding) that stabilize the interior of micelles and the exposed polar head groups, and explain how "like dissolves like" underpins these processes. -

Analyze Thermodynamics of Self-Assembly:

• Apply the concepts of Gibbs free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) to explain why micelle formation is enthalpically favored but entropically disfavored, and how the balance of these forces determines the spontaneous formation of micelles. -

Differentiate Between Single-Chain and Double-Chain Amphiphile Aggregation:

• Compare the structural differences between single-chain amphiphiles (forming micelles) and double-chain amphiphiles (forming bilayers and vesicles), and explain how the number of hydrophobic chains and the area per head group influence aggregate shape and stability. -

Understand Phase Behavior and Aggregate Transitions:

• Discuss how changes in conditions (e.g., concentration, temperature, pH) can lead to transitions in aggregate shape—from spherical micelles to cylindrical micelles and eventually to planar bilayers—and relate these transitions to changes in head group repulsion and chain packing. -

Integrate Laboratory and In Vivo Perspectives:

• Relate the insights obtained from in vitro experiments with simple lipid solutions to the more complex in vivo environment, where lipids interact with proteins and other molecules, influencing membrane formation, dynamics, and cellular function.

These goals aim to deepen your understanding of how lipid structure governs self-assembly, the underlying thermodynamics of micelle and bilayer formation, and the broader relevance of these principles to biological membranes.

Single Chain Amphiphiles and Micelles

Understanding lipids in simple solutions is essential to understanding them in vivo. The same physical-chemical constraints would apply to the complex environment of the cell. What is different in the cell is that lipids are found in a cellular environment crowded with proteins that bind, synthesize, and break down lipids. Nevertheless, we can apply what we know from the test tube experiments to the cell.

To understand how molecules might react, it helps to pretend you are a molecule and ask yourself what you would do! We want to know how lipid molecules, specifically single and double-chain amphiphiles, interact with each other and the solvent when added to water. Before you read the answer, look at the image below and ask yourself: What would I do if I were a single chain amphiphile and jumped into water as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)?

Here is what they do. When added to water, some single-chain amphiphiles dissolve while others form a monolayer on the water's surface. If enough enter the solution and exceed their net solubility, they self-aggregate to form micelles. These outcomes are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

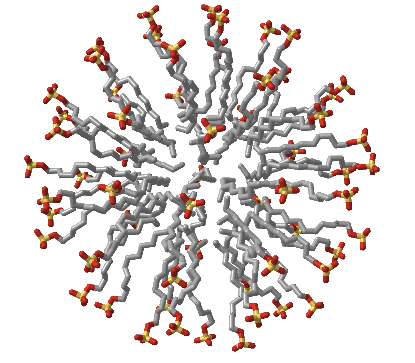

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of an sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) micelle

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) micelle (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: not available

Double-chain amphiphiles, in contrast, form bilayers instead of micelles. (Note: single and double-chain amphiphiles can also form other multimolecular aggregate structures, but micelles and bilayers are the most common and the only ones we will consider.)

The micelle interior is completely nonpolar. Spherical bilayers that enclose an aqueous compartment are called vesicles or liposomes. Micelles and bilayers, formed from single and double-chain amphiphiles, respectively, represent noncovalent aggregates and are formed by an entirely physical process. No covalent steps are required.

Common single-chain amphiphiles that form micelles are detergents (like sodium dodecyl sulfate - SDS) and fatty acids. Sodium hydroxide feels slippery on your skin since the base hydrolyses the fatty acids esterified to skin lipids. The free fatty acids then aggregate spontaneously to form micelles that act like detergents and are slippery.

Micelles/detergents in water are an example of an emulsion of two materials that are generally immiscible in each other unless one is dispersed into small droplets in the other. Fine oil drops can be dispersed in water, and fine aqueous drops can be dispersed in a nonpolar liquid. Many vaccines are formulated as this latter type of emulsion. Grease and oil in your clothes can be carried away by "diving" into the nonpolar part of the detergent micelle, which is dispersed in water as an emulsion. Another example of an emulsion or a colloid is a cloud, a dispersion of liquid water droplets in a solvent, the atmosphere.

The formation of these structures can be understood from the study of noncovalent interactions, as well as through thermodynamics. In a micelle, the buried acyl chains can interact and be stabilized by induced dipole-induced dipole forces as the nonpolar carbons and hydrogen are in van der Waals contact. They are sequestered from water. This view fits our simple axiom of "like-dissolves like." The polar head groups can be stabilized by ion-dipole bonds between charged head groups and water. Likewise, H-bonds between water and the head group stabilize the exposed head groups in water. Repulsive forces may also be involved. Head groups can repel each other through steric factors or ion-ion repulsion from like-charged head groups. The attractive forces must be greater than the repulsive forces, which lead to these molecular aggregates.

From a thermodynamic approach, one problem arises with this simple explanation. For a micelle or bilayer to form, many monomers must aggregate to form a single micelle or vesicle, which is entropically disfavored! So, let's delve into the thermodynamics of micelle formation.

ΔG, the free energy change for a reaction, determines the spontaneity and extent of a chemical or physical reaction. The system's free energy depends on three variables: temperature T, pressure P, and n, the number of moles of each substance. For the latter, think of solute X on two different sides of a permeable membrane. If the concentration of X is the same on each side, as shown in the system below, the system is in equilibrium, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

If the system is composed of two different parts, A and B, the system is at equilibrium (ΔG=0) if TA = TB, PA = PB, and the change in the absolute free energy per mole of A is ΔGA/Δn = ΔGB/Δn. More precisely, using simple calculus, we would discuss incremental changes in absolute free energy/mol, dGA/dn for A (often called the chemical potential of A, μA), and dGB/dn or μB)for B. At equilibrium, dGA/dn = dGB/dn. (We will use the symbol G here instead of μ). G is the absolute free energy/mol (again often called the chemical potential), where G=Go +RTln[A]. The equations you used in introductory chemistry can be written.

\begin{equation}

\begin{array}{l}

\Delta \mathrm{G}=\Delta \mathrm{G}^{0}+\mathrm{RTIn} \mathrm{Qr} \\

\Delta \mathrm{G}=\Delta \mathrm{H}-\mathrm{T} \Delta \mathrm{S} \\

\Delta \mathrm{G}^{0}=\Delta \mathrm{H}^{0}-\mathrm{T} \Delta \mathrm{S}^{0} \\

\Delta \mathrm{G}^{0}=-\mathrm{RTInK} \mathrm{eq}

\end{array}

\end{equation}

Now, let's apply this to the chemical equation for micelle formation:

n SCA <==> 1 micelle

where SCA represents a single-chain amphiphile. At first glance, we might suspect that:

- ΔH0 < 0 since the induced dipole-induced dipole interactions among the buried acyl chains in the micelle would be much more favorable than the water-acyl interactions for the monomeric amphiphile in the solution. Our aphorism supports this notion, "like dissolves like." Of course, we couldn't ignore polar interactions (H bonding, for example) among the head groups and water. Still, we might expect these to be equally favorable in the monomeric and micellar states.

- ΔS0 < 0 since we are forming a very ordered state (a single micelle) with much less entropy from a state (single chains of amphiphiles dispersed in solution) with much more entropy.

Hence, it would appear that micelle formation is enthalpically favored but entropically disfavored. Let's examine this issue more closely. First, we need to obtain a greater understanding of ΔGo, which should give us a clue as to where an SCA would "want" to be in this mixture. Remember, ΔG0 is a constant at a given T, P, and solvent conditions and depends only on the relative stability of a molecule in a given environment and not its concentration.

Traube, in 1891, noticed that single-chain amphiphiles tend to migrate to the surface of the water and decrease its surface tension (ST). He observed that the decrease in ST is directly proportional to the amount of amphiphile added until a certain point, at which point the added amphiphile has no additional effect. In other words, the response of ST saturates at some point.

We are more interested in what happens to amphiphiles in bulk water, not at the surface. As we showed in Figure 2 above, monomeric single-chain amphiphiles are in equilibrium with single-chain amphiphiles in micelles. Assume you have a way to measure a monomeric single-chain amphiphile in solution. What happens to its concentration as you add more and more SCA to the mixture? You observe the same effect that Traube noted with changes in surface tension. This explanation goes like this: as more amphiphile is added, more goes into the bulk solution as monomers. At some point, enough amphiphiles are added to form micelles. After this point, added amphiphiles form more micelles, and no further increases in monomeric single-chain amphiphiles are noted. The concentration of amphiphile at which this occurs is the critical micelle concentration (CMC). Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows a graph of a monomeric single-chain amphiphile in solution versus the concentration added to the solution.

This saturation effect can be observed with other systems as well.

- Consider the amount of NaCl(aq) in the solution as more NaCl(s) is added to water. The water is saturated with dissolved NaCl at some point, and no further increase in NaCl (aq) occurs.

- Consider the amount of a sparingly soluble hydrocarbon (HC) in water. After saturation, phase separation occurs.

Now consider the addition of a drop of a slightly soluble hydrocarbon liquid (HCL) into water, as pictured in the diagram below. At t=0, the system is not at equilibrium, and some of the HC will transfer from the pure liquid to water, so at time t=0, ΔGTOT < 0. This is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

The following equations can be derived.

\begin{equation}

\begin{array}{c}

\Delta \mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{TOT}}=\left(G_{\mathrm{HC}-\mathrm{W}}\right)-\left(G_{\mathrm{HC}-\mathrm{L}}\right)=\mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{HC}-\mathrm{W}}^{0}+R T \ln [\mathrm{HC}]_{\mathrm{W}}-\left(\mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{HC}-\mathrm{L}}^{0}+R T \ln [\mathrm{HC}]_{\mathrm{L}}\right)= \\

\Delta \mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{TOT}}=\left(\mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{HC}-\mathrm{W}}^{0}-\mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{HC}-\mathrm{L}}^{0}\right)+R T \ln \left([\mathrm{HC}]_{\mathrm{W}}-\ln [\mathrm{HC}]_{\mathrm{L}}\right)= \\

\Delta \mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{TOT}}=\Delta \mathrm{G}^{0}+R T \ln \frac{[\mathrm{HC}]_{\mathrm{W}}}{[\mathrm{HC}]_{\mathrm{L}}}

\end{array}

\end{equation}

Now, add a bit more complexity to the last example. Add a hydrocarbon x to a biphasic system of water and octanol and shake it vigorously as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). At equilibrium, x would have "partitioned" between the two mostly immiscible phases.

A simple favorable reaction can be written for this system: x aq → x oct.

If X is a hydrocarbon, ΔG < 0. Also, ΔGo < 0, since this term is independent of concentration and depends only on the intrinsic stability of x in water compared to that of octanol. This simple equation holds:

\begin{equation}

\Delta \mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{TOT}}=\left(\mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{oct}}^{0}-\mathrm{G}_{\mathrm{X}-\mathrm{w}}^{0}\right)+R T \ln \frac{[\mathrm{X}]_{\mathrm{oct}}}{[\mathrm{X}]_{\mathrm{w}}}=\Delta \mathrm{G}^{0}+R T \ln \frac{[\mathrm{X}]_{\mathrm{oct}}}{[\mathrm{X}]_{\mathrm{w}}}

\end{equation}

At equilibrium, ΔG0=0 and the equation can be rewritten as:

\begin{equation}

\Delta \mathrm{G}^{0}=-R T \ln \frac{[\mathrm{X}]_{\mathrm{oct}}}{[\mathrm{X}]_{\mathrm{w}}}=-\mathrm{RTlnK}_{\mathrm{part}}

\end{equation}

Kpart is the equilibrium partition coefficient for X in octanol and water. Kpart can readily be determined in the lab. Just shake a separatory flask with a biphasic system of octanol and water after injecting a bit of X. Then separate the layers and determine the concentration of X in each phase. Plug these numbers into the last equation. You should be able to predict the sign and relative magnitude of ΔGo since it does not depend on concentration but only on the intrinsic stability of the molecules in the different environments. Kpaft values are often determined for drugs since they often must diffuse across cell membranes to move into the cytoplasm, where they can act. Drugs, hence, must have a reasonable Kpart to pass through the membrane but not so high that they are insoluble.

Double Chain Amphiphiles and Bilayers

In contrast to single-chain amphiphiles, double-chain amphiphiles added to water form monolayers and vesicles called liposomes, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\).

They can be unilamellar, which consists of a single bilayer surrounding the internal aqueous compartment, or multilamellar, which consists of multiple bilayers surrounding the enclosed aqueous solution. Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) below shows images of a cross-section of a liposome/vesicle (diameter around 25 nm, so it is considered a small unilamellar vesicle or SUV). The bilayer is composed of 3298 DMPC (dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine) double-chain amphiphiles. The left image shows water molecules (over 9500) inside and outside the vesicle and the DMPCs as sticks, while the right image shows them in spacefill. Embedded in the top of the bilayer is the transmembrane helix of the cytokine receptor common subunit beta (PDB ID 2NA8), shown in red spacefill.

|

|

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Cross-section of a liposome/vesicle of diameter around 25 nm comprised of DMPC (dimyristoylphosphatidycholine), the transmembrane helix of the cytokine receptor common subunit beta (PDB ID 2NA8), and water molecules both inside and outside of the bilayer. PDB files and the images were made using MolCube and Pymol, respectively.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of 2NA8 with the bilayers shown as layers of dummy atoms and with no water molecules.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): 2NA8 with the bilayer represented with dummy atoms and with no water molecules. (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...vzJVvf3kSVuYb8

You can imagine that multilamellar vesicles resemble an onion with multiple layers. Cartoons of unilamellar and multilamellar liposomes are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\), where each concentric circle represents a bilayer.

Creative Commons Attribution License

Liposomes vary in diameter. They can be generally categorized into small (S, diameter < 25 nm), intermediate (I, diameter around 100 nm), and large (L, diameter from 250-1000 nm). If these vesicles are unilamellar, they are abbreviated as SUV, IUV, and LUV.

The chemical composition of liposomes made in the lab can be widely varied. Most contain neutral phospholipids like phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) or sphingomyelin (SM), supplemented, if desired, with negatively charged phospholipids, like phosphatidyl serine (PS) and phosphatidyl glycerol (PG). In addition, single-chain amphiphiles like cholesterol (C) and detergents can be incorporated into the bilayer membrane, which modulates the fluidity and transition temperature (Tm) of the bilayer. If present in too great a concentration, single-chain amphiphiles like detergents, which form micelles, can disrupt the membrane so completely that the double-chain amphiphiles become incorporated into detergent micelles, now called mixed micelles, in a process that effectively destroys the membrane bilayer.

The properties of liposomes (charge density, membrane fluidity, and permeability) are determined by the lipid composition and size of the vesicle. The desired properties will be, in turn, determined by the use of the particular liposome. The vesicles offer wonderful, simple models to study the biochemistry and biophysics of natural membranes. Membrane proteins can be incorporated into the liposome bilayer using the exact method you will be using. However, apart from these purposes, liposomes can encapsulate water-soluble molecules such as nucleic acids, proteins, and toxic drugs. These liposomes can be targeted to specific cells if antibodies or other molecules that will bind specifically to the target cell can be incorporated into the bilayer of the vesicle. Intraliposomal material may then be transferred into the cell by fusion of the vesicle with the cell or by endocytosis of the vesicle.

Liposomes could also be called lipid nanoparticles, with sizes ranging up to 1000 nm. Liposomes are vesicular, with small aqueous-filled compartments. They can be made with encapsulated drugs for delivery to target cells through blood transport. They act as an emulsion in water.

Lipid nanoparticles can also be particulate (insoluble), which slowly degrade and release their contents in situ. Most recently, particulate lipid nanoparticles have helped save the world by being used to encapsulate messenger RNA (mRNA) for the spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes the COVID-19 pandemic. These lipid nanoparticles are used in the vaccine against the coronavirus. The mRNA that encodes part of the spike protein is "encapsulated" in the lipid nanoparticle. The mRNA contains specially modified nucleotides to increase their stability. The lipid nanoparticles also contain positively charged lipids, which help stabilize the negatively charged mRNA from degradation. The nanoparticles are endocytosed into cells, where the mRNA can be translated into the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, required for whole virus entry into the cell. The immune system then recognizes the spike protein.

The lipids used in the formulation of these nanoparticles include fatty acids, mono-, di-, and triglycerols, glycerophospholipids, waxes (like cetyl palmitate), and other positively charged lipids including stearyl amine, benzalkonium chloride, cetrimide, cetyl pyridinium chloride, and dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide. These are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\): Amphiphiles used to make lipid nanoparticles

Why Micelles and Bilayers?

Micelles and liposomes form spontaneously - i.e., ΔG < 0. But why do single-chain amphiphiles form micelles and double-chain amphiphiles form bilayers? Let's think about this from a thermodynamic and structural point of view.

As the number of Cs in the nonpolar carbon (NC) chain increases, the ΔG for transferring into a micelle, or by analogy, for a single chain amphiphile entering a micelle, becomes more and more negative (i.e., more favored). The following equation seems to apply to the transfer of a single-chain amphiphile into a micelle:

ΔGo = Go (mic) - Go (aq) = + number - 709 NC

\begin{equation}

\Delta \mathrm{G}^{\circ}=\mathrm{G}^{\circ} \text { (mic) }-\mathrm{G}^{\circ}(\mathrm{aq})=+\text { number }-709 \mathrm{NC}

\end{equation}

where NC is the number of carbon atoms in the chain. The first positive term depends on the nature of the head group, while the second negative term is independent of the head group. These + and - terms bring us back to the principle of opposing forces we discussed when we looked at the noncovalent interactions involved in micelle and bilayer formation.

There are attractive interactions, including induced dipole-induced dipole interactions among the chains and dipole-ion and H-bond interactions with water and the head groups. Similar repulsive interactions arise from steric hindrance with bulky heady groups and ion-ion repulsions. Of course, there are also entropic considerations. Let us now consider these factors as we explore what might happen to a preformed micelle as we try to put more single-chain amphiphiles (sca) into it.

As we increase the number of Cs in the SCA, the micelles would have a larger radius. For a given SCA with a fixed number of Cs, once a spherical micelle is formed, it can no longer retain its spherical shape if more SCAs are added. Imagine increasing the diameter of a spherical micelle 10x. A large part of the inside would have no atoms or be filled with water, which would not be favorable. Therefore, if the micelle is to grow, it can do so only by changing shape to something other than a sphere. By squeezing a tennis ball, one can imagine that the shape could distort to a circular cylinder with end caps. In this way, the acyl chains can still interact. The only problem is that head groups will now be closer than they were in the sphere. This is simplistically illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\).

Imagine that in a sphere, the head groups radiate perpendicularly from the sphere's surface. As the sphere is distorted into a cylinder, the head groups come closer together, so they will experience more steric interference. If a cylinder can be formed, however, it could continue to grow as long as needed with no further compression required. Imagine you further compressed the cylinder into a planar "bilayer" structure. The head groups would be even closer and experience even more repulsion. This bilayer will not form since growth can occur in the cylindrical phase without the added repulsion.

Now consider a double-chain amphiphile (DCA). In the case of an SCA, the number (N) of head groups (HG) = the number of acyl chains (CH). Hence, the surface area per HG equals the area per HC. Or: As/N HG = As/ N CH. For a DCA, N HG = N CH/2, therefore As/N HG = 2As/NCH. There is twice the surface area available per head group compared to the SCA. Therefore, the DCA can tolerate more compression. It can easily be compressed to a bilayer, which, as we saw, has much less As/HG. The cylindrical form has too much space per head group since water can enter the structure. The extra closeness of head groups in the bilayer can be tolerated even more since the ΔGo for transfer of a DCA into a micelle is 60% more negative than that of an SCA. The As/HG for closed vesicles differs slightly from that of a truly planar bilayer since the vesicles are so large compared to a micelle.

Once again, we have discovered that structure mediates function. We can account for the fact that SCA and DCA form micelles and bilayers, respectively, by understanding the structure of the monomers!

In reality, things are more complicated.

The general rule holds that single-chain amphiphiles form micelles, and double-chain amphiphiles form bilayers. However, single-chain fatty acids can form bilayers under the right conditions if the pH is low enough that the head group is protonated and uncharged. Why would that make a difference? Fatty acids like oleic acid would be a candidate for components of the membranes of protocells in the evolution of life from abiotic conditions. Likewise, short double-chain amphiphiles can make micelles. A combination of double-chain amphiphiles with either short double-chain amphiphiles or single-chain amphiphiles can form a bicelle (a single structure with properties of both a bilayer and a micelle). In addition, other lipid phases can be observed. Which aggregates or phases ultimately form depends on the structure of the lipid, the solvent conditions, and the temperature. These include the following phases:

- lamellar gel (Lb) and lamellar liquid crystalline (La) phases

- hexagonal HI (cylinders packed in the shape of a hexagon with polar heads facing out into the water

- hexagonal HII (cylinders packed in the shape of a hexagon with acyl chains pointing out as in reverse micelles

- micellar (M).

We will discuss them in more detail in the next section.

Summary

This chapter explores how the physical-chemical properties of lipid molecules dictate their self-assembly in aqueous environments. This essential concept underpins our understanding of biological membranes and detergent function. Focusing on both single-chain and double-chain amphiphiles, the text explains how these molecules interact with water and with each other to form well-defined supramolecular structures.

Key Concepts:

-

Self-Assembly of Amphiphiles:

When introduced into water, single-chain amphiphiles can exist as dissolved monomers or form a monolayer at the water surface. Above a specific concentration, known as the critical micelle concentration (CMC), these molecules aggregate into micelles—spherical structures in which the hydrophobic acyl chains are sequestered away from water, while the polar head groups remain exposed to the aqueous environment. This behavior exemplifies the principle of "like dissolves like" and is governed by a balance of noncovalent interactions, such as van der Waals forces, ion-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonding. -

Thermodynamics of Micelle Formation:

The chapter delves into the thermodynamics driving self-assembly, using Gibbs free energy (ΔG) to describe the spontaneity of micelle formation. While aggregation is enthalpically favored (due to favorable interactions among hydrophobic chains), it is entropically disfavored because it leads to a decrease in molecular disorder. The net result—governed by the balance between these opposing forces—determines the stability and size of the micelle. -

Comparison with Double-Chain Amphiphiles:

In contrast to single-chain amphiphiles, double-chain amphiphiles (such as those found in membrane lipids) form bilayers rather than micelles. The presence of two hydrophobic chains per molecule allows for tighter packing and reduced steric repulsion between head groups, favoring the formation of planar bilayers that can assemble into vesicles (liposomes) with an internal aqueous compartment. -

Aggregate Phase Behavior:

The chapter also introduces the idea that the shape and size of lipid aggregates depend on the interplay between attractive forces (e.g., hydrophobic interactions) and repulsive forces (e.g., steric and ionic repulsions). As conditions change (e.g., concentration, temperature, pH), micelles can transition into other structures—such as cylindrical micelles or bilayers—demonstrating the versatile nature of lipid self-assembly. Various phase structures (lamellar, hexagonal, and micellar) are briefly mentioned as part of this dynamic behavior. -

Biological Relevance:

While these self-assembly processes are illustrated with simple in vitro systems, the same principles apply in the crowded, complex environment of cells. Here, lipids interact with proteins that bind, synthesize, or degrade them, yet the underlying thermodynamic and structural principles remain fundamentally important for understanding membrane formation and function.

In summary, the chapter ties together the structural characteristics of amphiphilic molecules with the thermodynamic forces driving their assembly into micelles and bilayers. This knowledge provides a critical foundation for understanding the behavior of lipids in both laboratory settings and living cells, and sets the stage for deeper exploration into membrane dynamics and lipid-protein interactions in subsequent chapters.