Spring_2024_Bis2A_Igo_Reading_07

- Page ID

- 133363

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives Associated with Spring_2024_Bis2A_Igo_Reading_07CS.1 Explain how molecules move in and out of cells. CS.2 Discuss the various functional roles carried out by a biological membrane. Invoke the Design Challenge to describe the problems they solve and the costs and benefits associated with their construction and use. CS.3 Describe the qualities and components of the plasma membrane. CS.4 Define and correctly use the properties of molecules that can travel through the plasma membrane and contrast them to properties that render other molecules incapable of penetrating the membrane. MS.22 Describe how the chemical structures and properties of lipids contribute to their functions (e.g. formation of membrane structures, contribution to membrane fluidity, etc.). |

Membranes

Plasma membranes enclose and define the borders between the inside and the outside of cells. They are typically composed of dynamic bilayers of phospholipids into which various other lipid-soluble molecules and proteins have also been embedded. These bilayers are asymmetric—the outer leaf differing from the inner leaf in lipid composition and in the proteins and carbohydrates that are displayed to either the inside or outside of the cell. One major function of the outer cell membrane is to communicate the cell’s unique identity to other cells. The proteins, lipids, and sugars displayed on the cell membrane allow for cells to be detected by and to interact with specific partners.

Various factors influence fluidity, permeability, and various other physical properties of the membrane. These include temperature, the configuration of the fatty acid tails (some are kinked by double bonds), sterols (i.e., cholesterol) embedded in the membrane, and the mosaic nature of the many proteins embedded within it. The plasma membrane is “selectively permeable”. This means it allows only some substances through while excluding others. In addition, the plasma membrane must, sometimes, be flexible enough to allow certain cells, such as amoebae, to change shape and direction as they move through the environment, hunting smaller, single-celled organisms.

Amoebae Hunting Video

Cellular membranes

A subgoal in our "build-a-cell" design challenge is to create a boundary that separates the "inside" of the cell from the environment "outside". This boundary needs to serve multiple functions that include:

- Act as a barrier by blocking some compounds from moving in and out of the cell.

- Be selectively permeable in order to transport specific compounds into and out of the cell.

- Receive, sense, and transmit signals from the environment to inside of the cell.

- Project "self" to others by communicating identity to other nearby cells.

Figure 1. The diameter of a typical balloon is 25cm and the thickness of the plastic of the balloon of around 0.25mm. This is a 1000X difference. A typical eukaryotic cell will have a cell diameter of about 50µm and a cell membrane thickness of 5nm. This is a 10,000X difference.

Fluid mosaic model

The fluid mosaic model describes the dynamic movement of the numerous proteins, sugars, and lipids embedded in the cell’s plasma membrane.

For some insight into the history of our understanding of the plasma membrane structure, click here.

It is sometimes useful to start our discussion by recalling the size of the cell membrane relative to the size of the entire cell cell. Plasma membranes range from 5 to 10 nm in thickness. For comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm wide, or approximately 1,000 times wider than a plasma membrane is thick. This means that the cellular barrier is very thin compared to the size of the volume it encloses. Despite this dramatic size differential, the cellular membrane must nevertheless still carry out its key barrier, transport and cellular recognition capacities and so must be a relatively “sophisticated” and dynamic structure.

Figure 2. The fluid mosaic model of the plasma membrane describes the plasma membrane as a fluid combination of phospholipids, cholesterol, and proteins. Carbohydrates attached to lipids (glycolipids) and to proteins (glycoproteins) extend from the outward-facing surface of the membrane.

The principal components of a plasma membrane are lipids (phospholipids and cholesterol), proteins, and carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are present only on the exterior surface of the plasma membrane and are attached to proteins, forming glycoproteins, or to lipids, forming glycolipids. The proportions of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates in the plasma membrane may vary with organism and cell type. In a typical human cell, proteins account for a massive 50 percent of the composition by mass, lipids (of all types) account for about 40 percent of the composition by mass, and carbohydrates account for the remaining 10 percent of the composition by mass. However, cellular functional specialization may cause these ratios of components to vary dramatically. For example, myelin, an outgrowth of the membrane of specialized cells, insulates the axons of the peripheral nerves, contains only 18 percent protein and 76 percent lipid. By contrast, the mitochondrial inner membrane contains 76 percent protein and only 24 percent lipid and the plasma membrane of human red blood cells is 30 percent lipid.

Phospholipids

Phospholipids are major constituents of the cell membrane. Phospholipids are made of a glycerol backbone to which two fatty acid tails and a phosphate group have been attached - one to each of each of the glycerol carbons atoms. The phospholipid is therefore an amphipathic molecule, meaning it has a hydrophobic part (fatty acid tails) and a hydrophilic part (phosphate head group).

Make sure to note in Figure 3 that the phosphate group has an R group linked to one of the oxygen atoms. R is a variable commonly used in these types of diagrams to indicate that some other atom or molecule is bound at that position. That part of the molecule can be different in different phospholipids—and will impart some different chemistry to the whole molecule. At the moment, however, you are responsible for being able to recognize this type of molecule (no matter what the R group is) because of the common core elements—the glycerol backbone, the phosphate group, and the two hydrocarbon tails.

Figure 3. A phospholipid is a molecule with two fatty acids and a modified phosphate group attached to a glycerol backbone. The phosphate may be modified by the addition of charged or polar chemical groups. Several chemical R groups may modify the phosphate. Choline, serine, and ethanolamine are shown here. These attach to the phosphate group at the position labeled R via their hydroxyl groups.

Attribution: Marc T. Facciotti (own work)

When many phospholipids are together exposed to an aqueous environment, they can spontaneously arrange themselves into various structures including micelles and phospholipid bilayers. The latter is the basic structure of the cell membrane. In a phospholipid bilayer, the phospholipids associate with one another into two oppositely-facing sheets. In each sheet nonpolar parts of the phospholipids face inward towards one another, composing the internal part of the membrane, and polar head groups facing oppositely to both the aqueous extracellular and intracellular environments.

Possible NB Discussion  Point

Point

Earlier in the course, we discussed the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which states that the overall entropy of the universe is always increasing. Apply this law in the context of the formation of the lipid bilayer membrane. How is it possible that the lipids are able to spontaneously arrange themselves into such an organized structure instead of scatter into a more disordered state? Or in other words -- if the second law holds true, then how exactly does the spontaneous lipid organization lead to increased entropy?

Figure 4. In the presence of water, some phospholipids will spontaneously arrange themselves into a micelle. The lipids will be arranged such that their polar groups will be on the outside of the micelle, and the nonpolar tails will be on the inside. A lipid bilayer can also form, a two layered sheet only a few nanometers thick. The lipid bilayer consists of two layers of phospholipids organized in a way that all the hydrophobic tails align side by side in the center of the bilayer and are surrounded by the hydrophilic head groups. Source: Created by Erin Easlon (own work)

Membrane proteins

Proteins make up the second major component of plasma membranes. Integral membrane proteins, as their name suggests, integrate completely into the membrane structure, and their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interact with the hydrophobic region of the phospholipid bilayer.

Some membrane proteins associate with only one half of the bilayer, while others stretch from one side of the membrane to the other, and are exposed to the environment on either side. Integral membrane proteins may have one or more transmembrane segments typically consisting of 20–25 amino acids. Within the transmembrane segments, hydrophobic amino acid variable groups arrange themselves to form a chemically complementary surface to the hydrophobic tails of the membrane lipids.

Peripheral proteins are found on only one side of the membrane, but never embed into the membrane. They can be on the intracellular side or the extracellular side, and weakly or temporarily associated with the membranes.

Figure 5. Integral membranes proteins may have one or more α-helices (pink cylinders) that span the membrane (examples 1 and 2), or they may have β-sheets (blue rectangles) that span the membrane (example 3). (credit: “Foobar”/Wikimedia Commons)

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are a third major component of plasma membranes. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids). These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2–60 monosaccharide units and can be either straight or branched. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other (one of the core functional requirements noted above.

Membrane fluidity

The integral proteins and lipids exist in the membrane as separate molecules and they "float" in the membrane, moving with respect to one another. The membrane is not like a balloon, however; because of the elastic properties of its plastic a balloon can easily grow and shrink its surface area without popping and while also maintaining the same rough circular shape. By contrast the plasma membrane is not able to withstand isotropic stretching or compression and can be easily popped when an imbalance of solute between inside and out causes water to rush in suddenly. A sudden loss of water will cause it to shrivel and wrinkle, dramatically changing the shape of the cell. it is fairly rigid and can burst if penetrated or if a cell takes in too much water and the membrane is stretched too far. However, because of its mosaic nature, a very fine needle can easily penetrate a plasma membrane without causing it to burst (the lipids flow around the needle point), and the membrane will self-seal when the needle is extracted.

Different organisms and cell types in multicellular organisms can tune fluidity of their membrane to be more compatible with specialized functions and/or in response to environmental factors. This tuning can be accomplished by adjusting the type and concentration of various components of the membrane, including the lipids, their degree of saturation, the lipids, their degree of saturation, the proteins, and other molecules like cholesterol. There are two other factors that help maintain this fluid characteristic. One factor is the nature of the phospholipids themselves. In their saturated form, the fatty acids in phospholipid tails are saturated with hydrogen atoms. There are no double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms, resulting in tails that are relatively straight. By contrast, unsaturated fatty acids do not have a full complement of hydrogen atoms on their fatty acid tails and therefore contain some double bonds between adjacent carbon atoms; a double bond results in a bend in the string of carbons of approximately 30 degrees.

Figure 6. Any given cell membrane will be composed of a combination of saturated and unsaturated phospholipids. The ratio of the two will influence the permeability and fluidity of the membrane. A membrane composed of completely saturated lipids will be dense and less fluid, and a membrane composed of completely unsaturated lipids will be very loose and very fluid.

Saturated fatty acids, with straight tails, are compressed by decreasing temperatures, and they will press in on each other, making a dense and fairly rigid membrane. Conversely, when unsaturated fatty acids are compressed, the “kinked” tails elbow adjacent phospholipid molecules away, maintaining some space between the phospholipid molecules. This “elbow room” helps to maintain fluidity in the membrane at temperatures at which membranes with high concentrations of saturated fatty acid tails would “freeze” or solidify. The relative fluidity of the membrane is particularly important in a cold environment. Many organisms (fish are one example) are capable of adapting to cold environments by changing the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in their membranes in response to the lowering of the temperature.

Cholesterol

Animal cells have cholesterol, an additional membrane constituent that assists in maintaining fluidity. Cholesterol, which lies right in between the phospholipids in the membrane, tends to dampen the effects of temperature on the membrane.Cholesterol both stiffens and increases membrane fluidity, depending on the temperature. Low temperatures cause phospholipids to pack together more tightly, creating a stiffer membrane. In this case, the cholesterol molecules serve to space the phospholipids apart and prevent the membrane from becoming totally rigid. Conversely, higher temperatures contribute to phospholipids moving farther apart from each other and therefore a more fluid membrane, but cholesterol molecules in the membrane take up space and prevent the complete dissociation of phospholipids.

Thus, cholesterol extends, in both directions, the range of temperature in which the membrane is appropriately fluid and consequently functional. Cholesterol also serves other functions, such as organizing clusters of transmembrane proteins into lipid rafts.

Figure 7. Cholesterol fits between the phospholipid groups within the membrane.

Review of the components of the membrane

| The components and functions of the plasma membrane | |

|---|---|

| Component | Location |

| Phospholipid | Main fabric of the membrane |

| Cholesterol | Between phospholipids and between the two phospholipid layers of animal cells |

| Integral proteins (e.g., integrins) | Embedded within the phospholipid layer(s); may or may not penetrate through both layers |

| Peripheral proteins | On the inner or outer surface of the phospholipid bilayer; not embedded within the phospholipids |

| Carbohydrates (components of glycoproteins and glycolipids) | Generally attached to proteins on the outside membrane layer |

Transport across the membrane

Design challenge problem and subproblems

General Problem: The cell membrane must simultaneously act as a barrier between "IN" and "OUT" and control specifically which substances enter and leave the cell and how quickly and efficiently they do so.

Subproblems: The chemical properties of molecules that must enter and leave the cell are highly variable. Some subproblems associated with this are: (a) Large and small molecules or collections of molecules must be able to pass across the membrane. (b) Both hydrophobic and hydrophilic substances must have access to transport. (c) Substances must be able to cross the membrane with and against concentration gradients. (d) Some molecules look very similar (e.g. Na+ and K+) but transport mechanisms must still be able to distinguish between them.

Energy story perspective

We can consider transport across a membrane from an energy story perspective; it is a process after all. For instance, at the beginning of the process a generic substance X may be on the inside or outside of the cell. At the end of the process, the substance will be on the opposite side from which it started.

e.g. X(in) ---> X(out),

where in and out refer to inside the cell and outside the cell, respectively.

At the beginning the matter in the system might be a very complicated collection of molecules inside and outside of the cell but with one molecule of X more inside the cell than out. At the end, there is one more molecule of X on the outside of the cell and one less on the inside. The energy in the system at the beginning is stored largely in the molecular structures and their motions and in electrical and chemical concentration imbalances across the cell membrane. The transport of X out of the cell will not change the energies of the molecular structures significantly but it will change the energy associated with the imbalance of concentration and or charge across the membrane. That is the transport will, like all other reactions, be exergonic or endergonic. Finally, some mechanism or sets of mechanisms of transport will need to be described.

One of the great wonders of the cell membrane is its ability to regulate the concentration of substances inside the cell. These substances include: ions such as Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl–; nutrients including sugars, fatty acids, and amino acids; and waste products, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), which must leave the cell.

The membrane’s lipid bilayer structure provides the first level of control. The phospholipids pack tightly, and the membrane has a hydrophobic interior. This structure alone creates what is known as a selectively permeable barrier, one that only allows substances meeting certain physical criteria to pass through it. In the case of the cell membrane, only relatively small, nonpolar materials can move through the lipid bilayer at biologically relevant rates (remember, the lipid tails of the membrane are nonpolar).

Selective permeability of the cell membrane refers to its ability to differentiate between different molecules, only allowing some molecules through while blocking others. Some of this selective property stems from the intrinsic diffusion rates for different molecules across a membrane. A second factor affecting the relative rates of movement of various substances across a biological membrane is the activity of various protein-based membrane transporters, both passive and active, that will be discussed in more detail in subsequent sections. First, we take on the notion of intrinsic rates of diffusion across the membrane.

Relative permeability

That different substances might cross a biological membrane at different rates should be relatively intuitive. There are differences in the mosaic composition of membranes in biology and differences in the sizes, flexibility, and chemical properties of molecules so it stands to reason that the permeability rates vary. It is a complicated landscape. The permeability of a substance across a biological membrane can be measured experimentally and we can report the rate of movement across a membrane in what are known as membrane permeability coefficients.

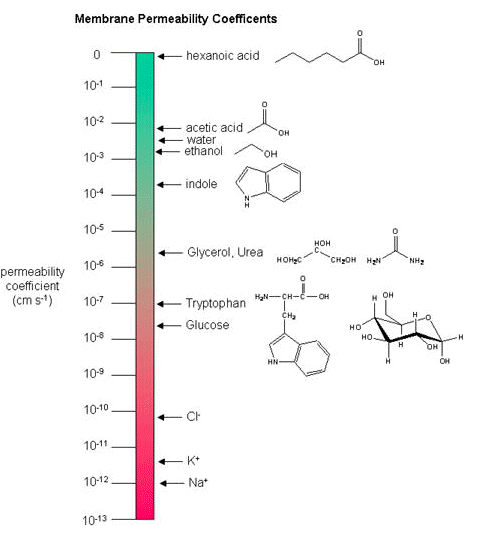

Membrane permeability coefficients

Below, we plot a variety of compounds with respect to their membrane permeability coefficients (MPC) as measured against a simple biochemical approximation of a real biological membrane. The reported permeability coefficient for this system is the rate at which simple diffusion through a membrane occurs and is reported in units of centimeters per second (cm/s). The permeability coefficient is proportional to the partition coefficient and is inversely proportional to the membrane thickness.

It is important that you can read and interpret the diagram below. The larger the coefficient, the more permeable the membrane is to the solute. For example, hexanoic acid is very permeable, a MPC of 0.9; acetic acid, water, and ethanol have MPCs between 0.01 and 0.001, and they are less permeable than hexanoic acid. Whereas ions, such as sodium (Na+), have an MPC of 10-12, and cross the membrane at a comparatively slow rate.

Figure 1. Membrane permeability coefficient diagram. The diagram was taken from BioWiki and can be found at http://biowiki.ucdavis.edu/Biochemis...e_Permeability.

While there are certain trends or chemical properties that can be roughly associated with a different compound permeability (small things go through "fast", big things "slowly", charged things not at all etc.), we caution against over-generalizing. The molecular determinants of membrane permeability are complicated and involve many factors including: the specific composition of the membrane, temperature, ionic composition, hydration; the chemical properties of the solute; the potential chemical interactions between the solute in solution and in the membrane; the dielectric properties of materials; and the energy trade-offs associated with moving substances into and out of various environments. So, in this class, rather than try to apply "rules" and try to develop too many arbitrary "cut-offs", we will strive to develop a general sense of some properties that can influence permeability and leave the assignment of absolute permeability to experimentally reported rates. In addition, we will also try to minimize the use of vocabulary that depends on a frame of reference. For instance, saying that compound A diffuses "quickly" or "slowly" across a bilayer only means something if the terms "quickly" or "slow" are numerically defined or the biological context is understood.

Osmosis

Osmosis is the movement of water through a semipermeable membrane according to the concentration gradient of water across the membrane, which is inversely proportional to the concentration of solutes. While diffusion transports material across membranes and within cells, osmosis transports only water across a membrane and the membrane limits the diffusion of solutes in the water. The aquaporins that facilitate water movement play a large role in osmosis, most prominently in red blood cells and the membranes of kidney tubules.

Mechanism

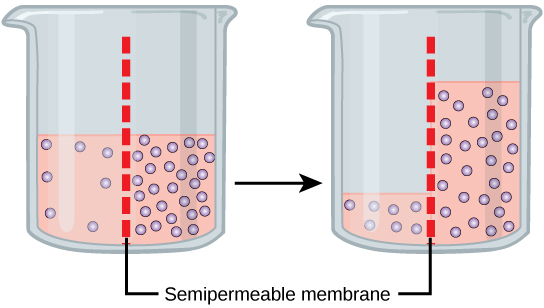

Osmosis is a special case of diffusion. Water, like other substances, moves from an area of high concentration to one of low concentration. An obvious question is what makes water move at all? Imagine a beaker with a semipermeable membrane separating the two sides or halves. On both sides of the membrane the water level is the same, but there are different concentrations of a dissolved substance, or solute, that cannot cross the membrane (otherwise the concentrations on each side would be balanced by the solute crossing the membrane). If the volume of the solution on both sides of the membrane is the same, but the concentrations of solute are different, then there are different amounts of water, the solvent, on either side of the membrane.

Figure 8. In osmosis, water always moves from an area of higher water concentration to one of lower concentration. In the diagram shown, the solute cannot pass through the selectively permeable membrane, but the water can.

To illustrate this, imagine two full glasses of water. One has a single teaspoon of sugar in it, whereas the second one contains one-quarter cup of sugar. If the total volume of the solutions in both cups is the same which cup contains more water? Because the large amount of sugar in the second cup takes up much more space than the teaspoon of sugar in the first cup, the first cup has more water in it.

Returning to the beaker example, recall that it has a mixture of solutes on either side of the membrane. A principle of diffusion is that the molecules move around and will spread evenly throughout the medium if they can. However, only the material capable of getting through the membrane will diffuse through it. In this example, the solute cannot diffuse through the membrane, but the water can. Water has a concentration gradient in this system. Thus, water will diffuse down its concentration gradient, crossing the membrane to the side where it is less concentrated. This diffusion of water through the membrane—osmosis—will continue until the concentration gradient of water goes to zero or until the hydrostatic pressure of the water balances the osmotic pressure. Osmosis proceeds constantly in living systems.

Tonicity

Tonicity describes how an extracellular solution can change the volume of a cell by affecting osmosis. A solution's tonicity often directly correlates with the osmolarity of the solution. Osmolarity describes the total solute concentration of the solution. A solution with low osmolarity has a greater number of water molecules relative to the number of solute particles; a solution with high osmolarity has less water molecules with respect to solute particles. In a situation in which solutions of two different osmolarities are separated by a membrane permeable to water, though not to the solute, water will move from the side of the membrane with lower osmolarity (and more water) to the side with higher osmolarity (and less water). This effect makes sense if you remember that the solute cannot move across the membrane, and thus the only component in the system that can move—the water—moves along its own concentration gradient. An important distinction that concerns living systems is that osmolarity measures the number of particles (which may be molecules) in a solution. Therefore, a solution that is cloudy with cells may have a lower osmolarity than a solution that is clear if the second solution contains more dissolved molecules than there are cells.

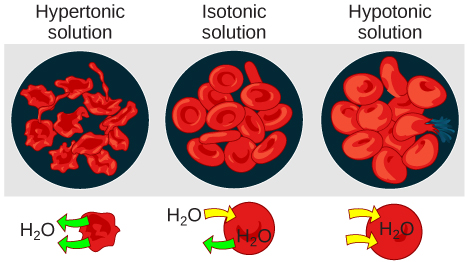

Hypotonic solutions

Three terms—hypotonic, isotonic, and hypertonic—are used to relate the osmolarity of a cell to the osmolarity of the extracellular fluid that contains the cells. In a hypotonic situation, the extracellular fluid has lower osmolarity than the fluid inside the cell, and water enters the cell (in living systems, the point of reference is always the cytoplasm, so the prefix hypo- means that the extracellular fluid has a lower concentration of solutes, or a lower osmolarity, than the cell cytoplasm). It also means that the extracellular fluid has a higher concentration of water in the solution than does the cell. In this situation, water will follow its concentration gradient and enter the cell.

Hypertonic solutions

As for a hypertonic solution, the prefix hyper- refers to the extracellular fluid having a higher osmolarity than the cell’s cytoplasm; therefore, the fluid contains less water than the cell does. Because the cell has a relatively higher concentration of water, water will leave the cell.

Isotonic solutions

In an isotonic solution, the extracellular fluid has the same osmolarity as the cell. If the osmolarity of the cell matches that of the extracellular fluid, there will be no net movement of water into or out of the cell, although water will still move in and out. Blood cells and plant cells in hypertonic, isotonic, and hypotonic solutions take on characteristic appearances.

Figure 9. Osmotic pressure changes the shape of red blood cells in hypertonic, isotonic, and hypotonic solutions. (credit: Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

Possible NB Discussion  Point

Point

Of course there is such thing as drinking too little water... but is there such thing as drinking too much water? Discuss what you think happens when you drink an excessive amount of water -- what is happening at the level of the cell membrane? What is happening to the cell size? Is drinking too much water actually a health hazard? Predict what would happen if we changed the beverage to Gatorade instead of water.

Tonicity in living systems

In a hypotonic environment, water enters a cell, and the cell swells. In an isotonic condition, the relative concentrations of solute and solvent are equal on both sides of the membrane. There is no net water movement; therefore, there is no change in the size of the cell. In a hypertonic solution, water leaves a cell and the cell shrinks. If either the hypo- or hyper- condition goes to excess, the cell’s functions become compromised, and the cell may be destroyed.

A red blood cell will burst, or lyse, when it swells beyond the plasma membrane’s capability to expand. Remember, the membrane resembles a mosaic, with discrete spaces between the molecules composing it. If the cell swells, and the spaces between the lipids and proteins become too large, and the cell will break apart.

In contrast, when excessive amounts of water leave a red blood cell, the cell shrinks. This has the effect of concentrating the solutes left in the cell, making the cytosol denser and interfering with diffusion within the cell. The cell’s ability to function will be compromised and may also result in the cell's death.

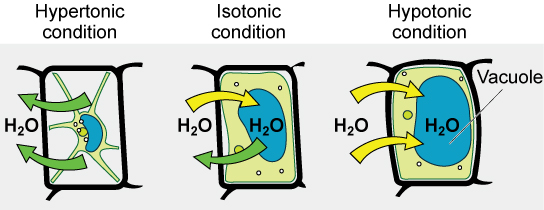

Various living things have ways of controlling the effects of osmosis—a mechanism called osmoregulation. Some organisms, such as plants, fungi, bacteria, and some protists, have cell walls that surround the plasma membrane and prevent cell lysis in a hypotonic solution. The plasma membrane can only expand to the limit of the cell wall, so the cell will not lyse. In fact, the cytoplasm in plants is always slightly hypertonic to the cellular environment, and water will always enter a cell if water is available. This inflow of water produces turgor pressure, which stiffens the cell walls of the plant. In nonwoody plants, turgor pressure supports the plant. Conversely, if the plant is not watered, the extracellular fluid will become hypertonic, causing water to leave the cell. In this condition, the cell does not shrink because the cell wall is not flexible. However, the cell membrane detaches from the wall and constricts the cytoplasm. This is called plasmolysis. Plants lose turgor pressure in this condition and wilt.

Figure 10. The turgor pressure within a plant cell depends on the tonicity of the solution that it is bathed in. (credit: modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal)

Figure 11. Without adequate water, the plant on the left has lost turgor pressure, visible in its wilting; the turgor pressure is restored by watering it (right). (credit: Victor M. Vicente Selvas)

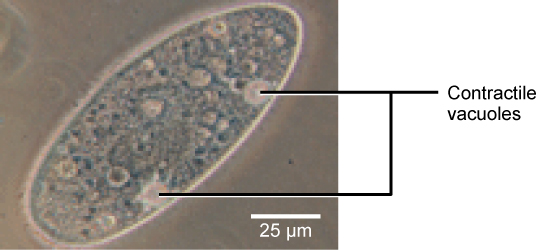

Tonicity is a concern for all living things. For example, paramecia and amoebas, which are protists that lack cell walls, have contractile vacuoles. This vesicle collects excess water from the cell and pumps it out, keeping the cell from bursting as it takes on water from its environment.

Figure 12. A paramecium’s contractile vacuole, here visualized using bright field light microscopy at 480x magnification, continuously pumps water out of the organism’s body to keep it from bursting in a hypotonic medium. (credit: modification of work by NIH; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Many marine invertebrates have internal salt levels matched to their environments, making them isotonic with the water in which they live. Fish, however, must spend approximately five percent of their metabolic energy maintaining osmotic homeostasis. Freshwater fish live in an environment that is hypotonic to their cells. These fish actively take in salt through their gills and excrete diluted urine to rid themselves of excess water. Saltwater fish live in the reverse environment, which is hypertonic to their cells, and they secrete salt through their gills and excrete highly concentrated urine.

In vertebrates, the kidneys regulate the amount of water in the body. Osmoreceptors are specialized cells in the brain that monitor the concentration of solutes in the blood. If the levels of solutes increase beyond a certain range, a hormone is released that retards water loss through the kidney and dilutes the blood to safer levels. Animals also have high concentrations of albumin, which is produced by the liver, in their blood. This protein is too large to pass easily through plasma membranes and is a major factor in controlling the osmotic pressures applied to tissues.