7.1.3: Temperature and Microbial Growth

- Page ID

- 42498

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Illustrate and briefly describe minimum, optimum, and maximum temperature requirements for growth

- Identify and describe different categories of microbes with temperature requirements for growth: psychrophile, psychrotolerant, mesophile, thermophile, hyperthermophile

- Give examples of microorganisms in each category of temperature tolerance

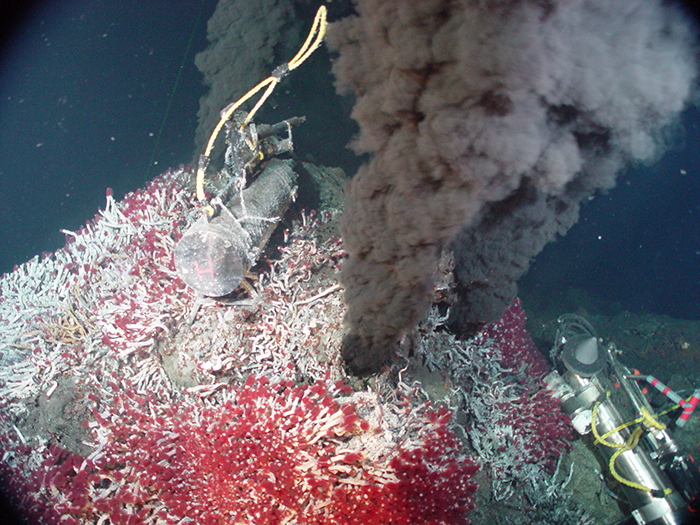

When the exploration of Lake Whillans started in Antarctica, researchers did not expect to find much life. Constant subzero temperatures and lack of obvious sources of nutrients did not seem to be conditions that would support a thriving ecosystem. To their surprise, the samples retrieved from the lake showed abundant microbial life. In a different but equally harsh setting, bacteria grow at the bottom of the ocean in sea vents (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), where temperatures can reach 340 °C (700 °F).

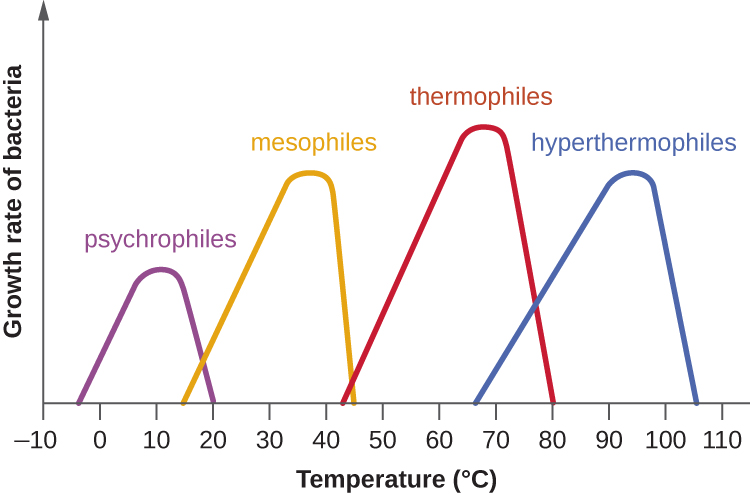

Microbes can be roughly classified according to the range of temperature at which they can grow. The growth rates are the highest at the optimum growth temperature for the organism. The lowest temperature at which the organism can survive and replicate is its minimum growth temperature. The highest temperature at which growth can occur is its maximum growth temperature. The following ranges of permissive growth temperatures are approximate only and can vary according to other environmental factors.

Organisms categorized as mesophiles (“middle loving”) are adapted to moderate temperatures, with optimal growth temperatures ranging from room temperature (about 20 °C) to about 45 °C. As would be expected from the core temperature of the human body, 37 °C (98.6 °F), normal human microbiota and pathogens (e.g., E. coli, Salmonella spp., and Lactobacillus spp.) are mesophiles.

Although their optimal growth temperatures resemeble those of mesophiles, organisms that are psychrotolerant, can survive in cooler environments, often down to refrigeration temperature about 4 °C. They are found in many natural environments in temperate climates. They are also responsible for the spoilage of refrigerated food.

The organisms retrieved from arctic lakes such as Lake Whillans are considered extreme psychrophiles (cold loving). Psychrophiles are microorganisms that have an optimal growth temperature at or below 15°C and can often grow at 0 °C or below. They usually do not survive at temperatures above 20 °C. They are found in permanently cold environments such as the deep waters of the oceans. Because they are active at low temperature, psychrophiles and psychrotolerant organisms are important decomposers in cold climates.

Organisms that grow at optimum temperatures of 50 °C to a maximum of 80 °C are called thermophiles (“heat loving”). They do not multiply at room temperature. Thermophiles are widely distributed in hot springs, geothermal soils, and manmade environments such as garden compost piles where the microbes break down kitchen scraps and vegetal material. Examples of thermophiles include Thermus aquaticus and Geobacillus spp. Higher up on the extreme temperature scale we find the hyperthermophiles, which are characterized by growth ranges from 80 °C to a maximum of 110 °C, with some extreme examples that survive temperatures above 121 °C, the average temperature of an autoclave. The hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean are a prime example of extreme environments, with temperatures reaching an estimated 340 °C (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Microbes isolated from the vents achieve optimal growth at temperatures higher than 100 °C. Noteworthy examples are Pyrobolus and Pyrodictium, archaea that grow at 105 °C and survive autoclaving. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the typical skewed curves of temperature-dependent growth for the categories of microorganisms we have discussed.

Life in extreme environments raises fascinating questions about the adaptation of macromolecules and metabolic processes. Very low temperatures affect cells in many ways. Membranes lose their fluidity and are damaged by ice crystal formation. Chemical reactions and diffusion slow considerably. Proteins become too rigid to catalyze reactions and may undergo denaturation. At the opposite end of the temperature spectrum, heat denatures proteins and nucleic acids. Increased fluidity impairs metabolic processes in membranes. Some of the practical applications of the destructive effects of heat on microbes are sterilization by steam, pasteurization, and incineration of inoculating loops. Proteins in psychrophiles are, in general, rich in hydrophobic residues, display an increase in flexibility, and have a lower number of secondary stabilizing bonds when compared with homologous proteins from mesophiles. Antifreeze proteins and solutes that decrease the freezing temperature of the cytoplasm are common. The lipids in the membranes tend to be unsaturated to increase fluidity. Growth rates are much slower than those encountered at moderate temperatures. Under appropriate conditions, mesophiles and even thermophiles can survive freezing. Liquid cultures of bacteria are mixed with sterile glycerol solutions and frozen to −80 °C for long-term storage as stocks. Cultures can withstand freeze drying (lyophilization) and then be stored as powders in sealed ampules to be reconstituted with broth when needed.

Macromolecules in thermophiles and hyperthermophiles show some notable structural differences from what is observed in the mesophiles. The ratio of saturated to polyunsaturated lipids increases to limit the fluidity of the cell membranes. Their DNA sequences show a higher proportion of guanine–cytosine nitrogenous bases, which are held together by three hydrogen bonds in contrast to adenine and thymine, which are connected in the double helix by two hydrogen bonds. Additional secondary ionic and covalent bonds, as well as the replacement of key amino acids to stabilize folding, contribute to the resistance of proteins to denaturation. The so-called thermoenzymes purified from thermophiles have important practical applications. For example, amplification of nucleic acids in the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) depends on the thermal stability of Taq polymerase, an enzyme isolated from T. aquaticus. Degradation enzymes from thermophiles are added as ingredients in hot-water detergents, increasing their effectiveness.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- What temperature requirements do most bacterial human pathogens have?

- What DNA adaptation do thermophiles exhibit?

Key Concepts and Summary

- Microorganisms thrive at a wide range of temperatures; they have colonized different natural environments and have adapted to extreme temperatures. Both extreme cold and hot temperatures require evolutionary adjustments to macromolecules and biological processes.

- Psychrophiles grow best in the temperature range of 0–15 °C whereas psychrotrophs thrive between 4°C and 25 °C.

- Mesophiles grow best at moderate temperatures in the range of 20 °C to about 45 °C. Pathogens are usually mesophiles.

- Thermophiles and hyperthemophiles are adapted to life at temperatures above 50 °C.

- Adaptations to cold and hot temperatures require changes in the composition of membrane lipids and proteins.

Contributors and Attributions

Nina Parker, (Shenandoah University), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University), Anh-Hue Thi Tu (Georgia Southwestern State University), Philip Lister (Central New Mexico Community College), and Brian M. Forster (Saint Joseph’s University) with many contributing authors. Original content via Openstax (CC BY 4.0; Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction)