34.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 105982

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

What is a Natural History Collection?

Historic definition: “Anything connected with NATURE.”

Modern definition: Definitions from biologists often focus on the scientific study of individual organisms in their environment.

"Natural history is the study of animals and plants – of organisms. ... I like to think, then, of natural history as the study of life at the level of the individual – of what plants and animals do, how they react to each other and their environment, how they are organized into larger groupings like populations and communities“- Marston Bates, 1954

"The close observation of organisms—their origins, their evolution, their behavior, and their relationships with other species“- D.S. Wilcove and T. Eisner, 2000

Marston Bates, The nature of natural history, Scribners, 1954.

D. S Wilcove and T. Eisner, "The impending extinction of natural history," Chronicle of Higher Education 15 (2000): B24

Paleolithic cave paintings- identified “species”

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Chauvet horses(opens in new window) ~31,000BP is licensed under Public Domain(opens in new window)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Altamira Bison(opens in new window) by Rameessos is licensed under Public Domain(opens in new window)

Early Natural History

Naturalists: Gaining much knowledge, but no durable preservation techniques

Bacteria and microbes were unknown

Drawings and written descriptions only

- Aristotle (History of Animals)

- Aelian (De Natura Animalium)

- Pliny the Elder (Natural History)

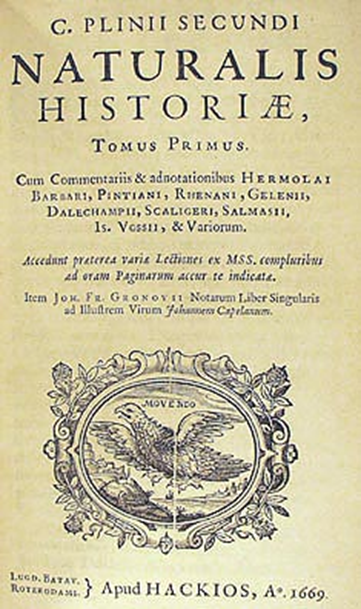

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Naturalis Historia, 1669 edition, title page. The title at the top reads: "Volume I of the Natural History of Gaius Plinius Secundus".

Why Collect Specimens?

Article: Why Collections Matter(opens in new window) from The Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections [SPNHC] - an international organization devoted to the preservation, conservation and management of natural history collections.

1. A physical record to identify new species and subspecies. New, unidentified species can be compared to "type specimens" to determine relatedness.

- Holotype- a single type specimen upon which the description and name of a new species is based.

- Paratype- a specimen of an organism that helps define what the scientific name of a species actually represents, but it is not the holotype.

- Topotype- a specimen of a species collected at the locality at which the original type was obtained.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): [Ichthyology • 2013] Spectrolebias brousseaui • A New Annual Fish (Cyprinodontiformes: Rivulidae: Cynolebiatinae) from the upper río Mamoré basin, Bolivia

- Monitor physical &/or physiological changes in a population. (See the case studies below for examples.)

- Law enforcement- identify endangered species and wildlife trafficking.

- Tissue samples for contaminant/disease analysis. (See the case studies below for examples.)

- Isotope analysis for determining relatedness or territory distributions, or in the case of Arctic waders, determining how they utilize nutrients to make eggs.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Arctic waders are “income breeders,” not “capital breeders” from Klaassen, M., Lindström, Å., Meltofte, H. et al. Arctic waders are not capital breeders. Nature 413, 794 (2001). [doi.org]

- Detailed scientific drawings for field identification guides

- “Teaching collections” which allow students to see and hold various species from other parts of the world.

Types of collections

Microbiological- World Federation of Culture Collections(opens in new window)

Fungi- USDA Database(opens in new window)

Plants- Plant Collection Network- NA(opens in new window)

Invertebrates- Field Museum, Chicago

Herpetological- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History(opens in new window)

Fish- Northern Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences(opens in new window)

Avian- Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology

Mammals- American Museum of Natural History(opens in new window)

The History of Collecting

Collecting natural history and geological specimens was a “fad” in the 18th and 19th centuries. Conservation of species was not considered, and collectors gathered as much as they could to sell to the public. Those in the military would often collect specimens from overseas while on deployment.

"Market collectors took about 10 million Common Murre eggs between 1850 and 1900 from the Farallon Islands off the northern Californian coast, for sale to markets and restaurants in San Francisco. Good egg collectors took egg clutches early in a field season so that birds could re-lay; in contrast, destructive egg collectors would take all of the eggs of all of the birds in a locality – for example, a nesting colony – during the entire breeding season. This type of collecting, combined with the detrimental effects of the millinery trade on birds, caused outrage among ornithologists and interested lay-people around the world, and led to the enaction of laws in the early 20th century limiting bird and egg collecting to those specimens needed only for scientific purposes.”- from WFVZ The History of Bird and Egg Collecting(opens in new window)

Laws on Collecting

In the UK, it is illegal to sell eggs, regardless of age.

In the US, State and Federal permits are required to “take” or “salvage” specimens, and to “house” collections- Scientific Collecting permits- California Dept of Fish and Wildlife(opens in new window)

Must follow Endangered Species Act(opens in new window) and CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora)(opens in new window) laws.

The primary sources for animal specimens currently are wildlife rehabilitation organizations; wildlife research agencies; birds killed by cats, window strikes, and car impacts. It is rare to actively go out into the wild to collect animal specimens.

It's All About The Data!

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Labels on specimen- Original tag and museum catalog tag (From Field Museum of Natural History.)

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Data card- More in-depth information kept on file at the museum where the specimen is housed (from The WFVZ)

Methods of preservation

Study skins- skin of animal preserved, often with bones intact

Mammals, birds, reptiles, (and fish)

Flat skin- For large animals that take up a large amount of space

Nests

Egg- egg blowing

Spirit specimens

Skeletons

Fossils

Plant press

Seed banks

Case Study- Influenza

1918 influenza outbreak- 20 million to 40 million people were killed worldwide, including 675,000 people in the United States (peak of 10,000 per week) (Crosby 1989). Influenza virus from preserved bird specimens in the Smithsonian was compared with that in tissue samples from humans infected in 1918 (Taubenberger et al. 1997, Fanning et al. 2002).

These studies showed that the virus responsible for the 1918 pandemic was more similar to strains infecting swine and humans than to avian influenza, suggesting that the pandemic was not caused by the virus jumping from birds to humans, as previously suspected.

Other recent studies have used historical samples to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the virus, providing guidance for future vaccine development (e.g., Ferguson et al. 2003)

[academic.oup.com]

Case Study- Hantavirus

In 1993, the hantavirus outbreak in SW United States killed 70 percent of afflicted individuals. The virus had been found in deer mice in the Southwest before the human outbreak, but little was known about its abundance in natural populations or the causes for its sudden jump into human populations (Yates et al. 2002).

Some citizens expressed concern that the new human infections might be linked to military weapons testing at nearby Fort Wingate (Horgan 1993).

Genetic analysis conclusively showed that hantavirus had been present in rodent populations before the 1993 outbreak, and the close relationships between different strains of the virus and different rodent hosts suggested an ancient association between virus and host (Yates et al. 2002).

Wet El Nino years allow rodent populations to expand, and increase the probability of infecting humans.

[academic.oup.com]

Case Study- Lead Poisoning

California Condors (Gymnogyps californianus) were brought to the brink of extinction, in part, because of lead poisoning, and lead poisoning remains a significant threat today. Condors in California remain chronically exposed to harmful levels of lead. 30% of the annual blood samples collected from condors indicate lead exposure (blood lead ≥ 200 ng/mL) that causes significant subclinical health effects. Each year, ∼20% of free-flying birds have blood lead levels (≥450 ng/mL) that indicate the need for clinical intervention to avert morbidity and mortality.

Lead isotopic analysis shows that lead-based ammunition is the principle source of lead poisoning in condors.

The condor’s apparent recovery is solely because of intensive ongoing management, with the only hope of achieving true recovery dependent on the elimination or substantial reduction of lead poisoning rates.

[www.pnas.org]

Case study- Mercury

More than 1.6 million Americans are at risk of mercury poisoning. Mercury deposition in fish is the leading cause of governmental advisories against fish consumption in the United States—over 2200 such advisories were issued in 2000 (EPA 2002, Stoner 2002.) Researchers can estimate historical levels of contamination in museum specimens, and construct a baseline against which current levels can be compared.

Analysis of preserved bird specimens from the Swedish Museum of Natural History has shown that concentrations of accumulated mercury increased during the 1940s and 1950s, probably as a result of human industry (Berg et al. 1966)

Museum collections can also be used to allay unwarranted fears. Some studies have demonstrated that the accumulation of toxic compounds, such as mercury, is not occurring in all oceanic fish (Barber et al. 1972, Miller et al. 1972).

Notable Collections

Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy(opens in new window)

Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology(opens in new window)

Local Natural History Collections

U.C. Berkeley- Museum of Vertebrate Zoology(opens in new window)