6.2.1: Gene Expression in Evolution

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 102513

Learning Objectives

- Using examples, describe how changes in gene expression can be association with changes in phenotype and evolution.

Mutations can occur in both cis-elements and trans-factors; both can result in altered patterns of gene expression. If an altered pattern of gene expression results in a selective advantage (or at least do not produce a major disadvantage), they may be selected and maintained in future populations. They may even contribute to the evolution of new species. An example of a sequence change in an enhancer is found in the Pitx gene.

Pitx expression in Stickleback

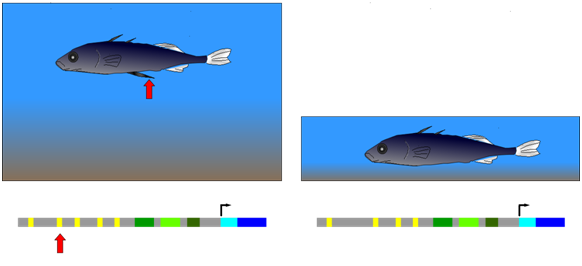

The three-spined stickleback provides an example of natural selection of a mutation in a cis-regulatory element. This fish occurs in two forms: (1) populations that inhabit deep, open water and have a spiny pelvic fin that deters larger predator fish from feeding on them; (2) populations from shallow water environments and lack this spiny pelvic fin. In shallow water, it appears that a long, spiny pelvic fin would be a disadvantage because it frequently contacts the sediment at the bottom of the pond and allows parasitic insects in the sediment to invade the stickleback. Researchers compared gene sequences of individuals from both deep and shallow water environments. They observed that in embryos from the deep-water population, a gene called Pitx was expressed in several groups of cells, including those that developed into the pelvic fin. Embryos from the shallow-water population expressed Pitx in the same groups of cells as the other population, with an important exception: Pitx was not expressed in the pelvic fin primordium (the cells that will generate the fin) in the shallow-water population. Further genetic analysis showed that the absence of Pitx gene expression from the developing pelvic fin of shallow-water stickleback was due to the absence (mutation) of a particular enhancer element upstream of Pitx.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Development of a large, spiny pelvic fin in deep-water stickleback (left) depends on the presence of a particular enhancer element upstream of a gene called Pitx. Mutants lacking this element, and therefore the large pelvic fin (right), have been selected for in shallow-water environments. (Wikipedia-Richard Wheeler-GFDL)

Thinking about the mutation

Consider the enhancer element mutated in the shallow-water sticklebacks:

- What is the function of that DNA sequence? What type of protein would bind there?

- Do you think this mutation acts in a dominant or recessive manner?

- Which of these processes are affected by the mutation: DNA replication, transcription, splicing, and/or translation?

- Would it be possible for another mutation to reverse the effects of this mutation and a shallow-water stickleback with a long fin?

Example: Hemoglobin expression in placental mammals.

Hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying component of red blood cells (erythrocytes). Hemoglobin usually exists as tetramers of four non-covalently bound hemoglobin molecules. Each hemoglobin molecule consists of a globin polypeptide with a covalently attached heme molecule. Heme is made through a specialized metabolic pathway and is then bound to globin polypeptide through post-translational modification.

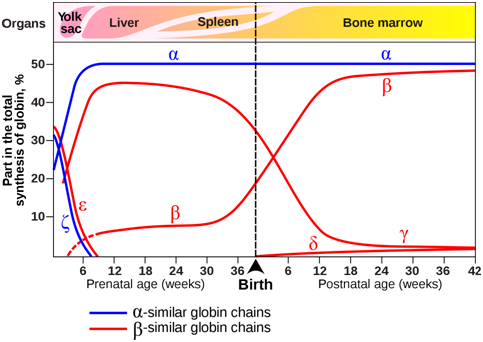

The composition of the hemoglobin tetramers changes during development. From early childhood onward, most tetramers are of the type \(\alpha\)2\(\beta\)2, which means they contain of two copies of each of two slightly different globin proteins named \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). A small amount of adult hemoglobin is \(\alpha\)2\(\delta\)2, which has \(\delta\) globin instead of the more common \(\beta\) globin. Other tetrameric combinations predominate before birth: \(\zeta\)2\(\varepsilon\)2 is most abundant in embryos, and \(\alpha\)2\(\gamma\)2 is most abundant in fetuses. Although the six globin proteins (\(\alpha\) = alpha, \(\beta\) = beta , \(\gamma\) = gamma, \(\delta\) =delta, \(\varepsilon\) =epsilon , \(\zeta\) = zeta) are very similar to each other, they do have slightly different functional properties. For example, fetal hemoglobin has a higher oxygen affinity than adult hemoglobin, allowing the fetus to more effectively extract oxygen from maternal blood. The specialized \(\gamma\) globin genes that are characteristic of fetal hemoglobin are found only in placental mammals.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Expression of globin genes during prenatal and postnatal development in humans. The organs in which globin genes are primarily expressed at each developmental stage are also indicated. (Origianl-Deyholos-CC:AN)

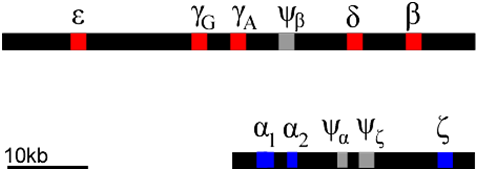

Each of these globin polypeptides is encoded by a different gene. In humans, globin genes are located in clusters on two chromosomes. We can infer that these clusters arose through a series of duplications of an ancestral globin gene. Gene duplication events can occur through rare errors in processes such as DNA replication, meiosis, or transposition (5.2: Changes in Chromosome Structure). The duplicated genes can then accumulate mutations independently of each other. Mutations can occur in either the regulatory regions (e.g. promoter regions), or in the coding regions, or both. In this way, the promoters of globin genes have evolved to be expressed at different phases of development, and to produce proteins optimized for the prenatal environment.

Of course, not all mutations are beneficial: some mutations can lead to inactivation of one or more of the products of a gene duplication. This can produce what is called a pseudogene. Examples of pseudogenes (\(\psi\)) are also found in the globin clusters. Pseudogenes have mutations that prevent them from being expressed at all. The globin genes provide an example of how gene duplication and mutation, followed by selection, allows genes to evolve specialized expression patterns and functions. Many genes have evolved as gene families in this way, although they are not always clustered together as are the globins.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Individuals with diseases such as sickle cell disease or \(\beta\)-thalassemia have mutations that either cause a malformed protein or the absence of the HBB (beta-globin) protein. How could understanding the normal expression of other hemoglobin proteins help develop new therapies for these patients? What tools and processes might be used?

- Answer

-

Recent clinical trials are exploring the possibility of using gene editing to express fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell and beta-thalessemia patients. This process isolates stem cells from patients, edits the DNA in vitro, and then transplants the edited cells back into the patient (reviewed in https://academic.oup.com/hmg/advance-article/doi/10.1093/hmg/ddaa088/5836961).

A news report about one of these patients is at this link https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/06/23/877543610/a-year-in-1st-patient-to-get-gene-editing-for-sickle-cell-disease-is-thriving.

Selected references:

Ye L, Wang J, Tan Y, et al. (2016) Genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9 to create the HPFH genotype in HSPCs: An approach for treating sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(38):10661-10665. doi:10.1073/pnas.1612075113 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5035856/)

Weber L, Frait G, Felix T, et al. (2020) Editing a γ-globin repressor binding site restores fetal hemoglobin synthesis and corrects the sickle cell disease phenotype. Science Advances 12 Feb 2020 (https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/6/7/eaay9392?utm_source=TrendMD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=TrendMD_1)

Demirci S, Leonard A, Tisdale JF. (2020) Genome editing strategies for fetal hemoglobin induction in beta-hemoglobinopathies. Human Molecular Genetics 14 May 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddaa088

Contributors and Attributions

Dr. Todd Nickle and Isabelle Barrette-Ng (Mount Royal University) The content on this page is licensed under CC SA 3.0 licensing guidelines.