14.6: DNA Repair

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 74574

Skills to Develop

- Discuss the different types of mutations in DNA

- Explain DNA repair mechanisms

DNA replication is a highly accurate process, but mistakes can occasionally occur, such as a DNA polymerase inserting a wrong base. Uncorrected mistakes may sometimes lead to serious consequences, such as cancer. Repair mechanisms correct the mistakes. In rare cases, mistakes are not corrected, leading to mutations; in other cases, repair enzymes are themselves mutated or defective.

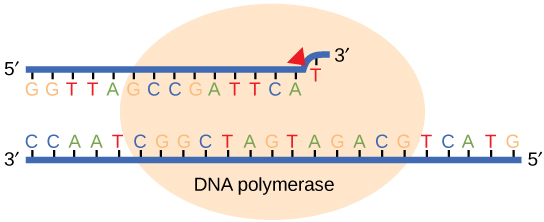

Most of the mistakes during DNA replication are promptly corrected by DNA polymerase by proofreading the base that has been just added (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). In proofreading, the DNA pol reads the newly added base before adding the next one, so a correction can be made. The polymerase checks whether the newly added base has paired correctly with the base in the template strand. If it is the right base, the next nucleotide is added. If an incorrect base has been added, the enzyme makes a cut at the phosphodiester bond and releases the wrong nucleotide. This is performed by the exonuclease action of DNA pol III. Once the incorrect nucleotide has been removed, a new one will be added again.

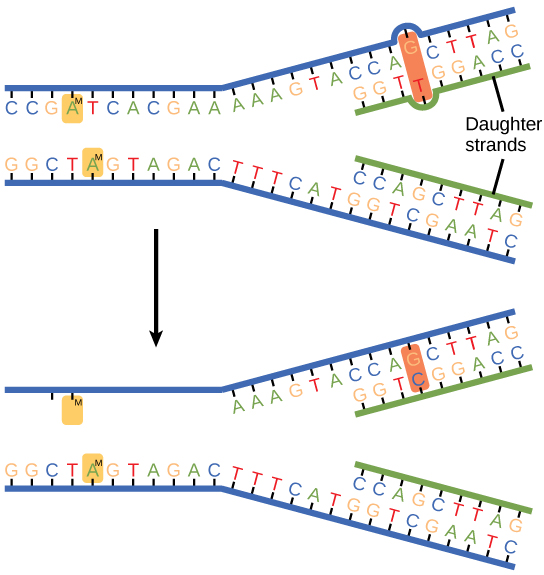

Some errors are not corrected during replication, but are instead corrected after replication is completed; this type of repair is known as mismatch repair (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The enzymes recognize the incorrectly added nucleotide and excise it; this is then replaced by the correct base. If this remains uncorrected, it may lead to more permanent damage. How do mismatch repair enzymes recognize which of the two bases is the incorrect one? In E. coli, after replication, the nitrogenous base adenine acquires a methyl group; the parental DNA strand will have methyl groups, whereas the newly synthesized strand lacks them. Thus, DNA polymerase is able to remove the wrongly incorporated bases from the newly synthesized, non-methylated strand. In eukaryotes, the mechanism is not very well understood, but it is believed to involve recognition of unsealed nicks in the new strand, as well as a short-term continuing association of some of the replication proteins with the new daughter strand after replication has completed.

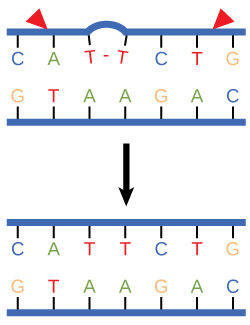

In another type of repair mechanism, nucleotide excision repair, enzymes replace incorrect bases by making a cut on both the 3' and 5' ends of the incorrect base (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The segment of DNA is removed and replaced with the correctly paired nucleotides by the action of DNA pol. Once the bases are filled in, the remaining gap is sealed with a phosphodiester linkage catalyzed by DNA ligase. This repair mechanism is often employed when UV exposure causes the formation of pyrimidine dimers.

A well-studied example of mistakes not being corrected is seen in people suffering from xeroderma pigmentosa (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Affected individuals have skin that is highly sensitive to UV rays from the sun. When individuals are exposed to UV, pyrimidine dimers, especially those of thymine, are formed; people with xeroderma pigmentosa are not able to repair the damage. These are not repaired because of a defect in the nucleotide excision repair enzymes, whereas in normal individuals, the thymine dimers are excised and the defect is corrected. The thymine dimers distort the structure of the DNA double helix, and this may cause problems during DNA replication. People with xeroderma pigmentosa may have a higher risk of contracting skin cancer than those who dont have the condition.

Errors during DNA replication are not the only reason why mutations arise in DNA. Mutations, variations in the nucleotide sequence of a genome, can also occur because of damage to DNA. Such mutations may be of two types: induced or spontaneous. Induced mutations are those that result from an exposure to chemicals, UV rays, x-rays, or some other environmental agent. Spontaneous mutations occur without any exposure to any environmental agent; they are a result of natural reactions taking place within the body.

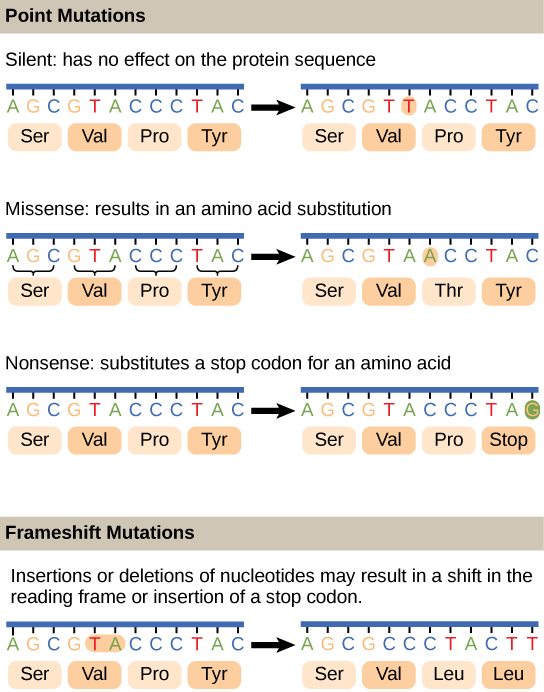

Mutations may have a wide range of effects. Some mutations are not expressed; these are known as silent mutations. Point mutations are those mutations that affect a single base pair. The most common nucleotide mutations are substitutions, in which one base is replaced by another. These can be of two types, either transitions or transversions. Transition substitution refers to a purine or pyrimidine being replaced by a base of the same kind; for example, a purine such as adenine may be replaced by the purine guanine. Transversion substitution refers to a purine being replaced by a pyrimidine, or vice versa; for example, cytosine, a pyrimidine, is replaced by adenine, a purine. Mutations can also be the result of the addition of a base, known as an insertion, or the removal of a base, also known as deletion. Sometimes a piece of DNA from one chromosome may get translocated to another chromosome or to another region of the same chromosome; this is also known as translocation. These mutation types are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A frameshift mutation that results in the insertion of three nucleotides is often less deleterious than a mutation that results in the insertion of one nucleotide. Why?

- Answer

-

If three nucleotides are added, one additional amino acid will be incorporated into the protein chain, but the reading frame won't shift.

Mutations in repair genes have been known to cause cancer. Many mutated repair genes have been implicated in certain forms of pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, and colorectal cancer. Mutations can affect either somatic cells or germ cells. If many mutations accumulate in a somatic cell, they may lead to problems such as the uncontrolled cell division observed in cancer. If a mutation takes place in germ cells, the mutation will be passed on to the next generation, as in the case of hemophilia and xeroderma pigmentosa.

Summary

DNA polymerase can make mistakes while adding nucleotides. It edits the DNA by proofreading every newly added base. Incorrect bases are removed and replaced by the correct base, and then a new base is added. Most mistakes are corrected during replication, although when this does not happen, the mismatch repair mechanism is employed. Mismatch repair enzymes recognize the wrongly incorporated base and excise it from the DNA, replacing it with the correct base. In yet another type of repair, nucleotide excision repair, the incorrect base is removed along with a few bases on the 5' and 3' end, and these are replaced by copying the template with the help of DNA polymerase. The ends of the newly synthesized fragment are attached to the rest of the DNA using DNA ligase, which creates a phosphodiester bond.

Most mistakes are corrected, and if they are not, they may result in a mutation defined as a permanent change in the DNA sequence. Mutations can be of many types, such as substitution, deletion, insertion, and translocation. Mutations in repair genes may lead to serious consequences such as cancer. Mutations can be induced or may occur spontaneously.

Glossary

- induced mutation

- mutation that results from exposure to chemicals or environmental agents

- mutation

- variation in the nucleotide sequence of a genome

- mismatch repair

- type of repair mechanism in which mismatched bases are removed after replication

- nucleotide excision repair

- type of DNA repair mechanism in which the wrong base, along with a few nucleotides upstream or downstream, are removed

- proofreading

- function of DNA pol in which it reads the newly added base before adding the next one

- point mutation

- mutation that affects a single base

- silent mutation

- mutation that is not expressed

- spontaneous mutation

- mutation that takes place in the cells as a result of chemical reactions taking place naturally without exposure to any external agent

- transition substitution

- when a purine is replaced with a purine or a pyrimidine is replaced with another pyrimidine

- transversion substitution

- when a purine is replaced by a pyrimidine or a pyrimidine is replaced by a purine