5.2: Components and Structure - Fluid Mosaic Model

- Page ID

- 12739

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe the fluid mosaic model of cell membranes

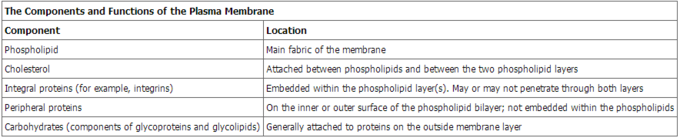

The fluid mosaic model was first proposed by S.J. Singer and Garth L. Nicolson in 1972 to explain the structure of the plasma membrane. The model has evolved somewhat over time, but it still best accounts for the structure and functions of the plasma membrane as we now understand them. The fluid mosaic model describes the structure of the plasma membrane as a mosaic of components —including phospholipids, cholesterol, proteins, and carbohydrates—that gives the membrane a fluid character. Plasma membranes range from 5 to 10 nm in thickness. For comparison, human red blood cells, visible via light microscopy, are approximately 8 µm wide, or approximately 1,000 times wider than a plasma membrane. The proportions of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates in the plasma membrane vary with cell type. For example, myelin contains 18% protein and 76% lipid. The mitochondrial inner membrane contains 76% protein and 24% lipid.

The main fabric of the membrane is composed of amphiphilic or dual-loving, phospholipid molecules. The hydrophilic or water-loving areas of these molecules are in contact with the aqueous fluid both inside and outside the cell. Hydrophobic, or water-hating molecules, tend to be non- polar. A phospholipid molecule consists of a three-carbon glycerol backbone with two fatty acid molecules attached to carbons 1 and 2, and a phosphate-containing group attached to the third carbon. This arrangement gives the overall molecule an area described as its head (the phosphate-containing group), which has a polar character or negative charge, and an area called the tail (the fatty acids), which has no charge. They interact with other non-polar molecules in chemical reactions, but generally do not interact with polar molecules. When placed in water, hydrophobic molecules tend to form a ball or cluster. The hydrophilic regions of the phospholipids tend to form hydrogen bonds with water and other polar molecules on both the exterior and interior of the cell. Thus, the membrane surfaces that face the interior and exterior of the cell are hydrophilic. In contrast, the middle of the cell membrane is hydrophobic and will not interact with water. Therefore, phospholipids form an excellent lipid bilayer cell membrane that separates fluid within the cell from the fluid outside of the cell.

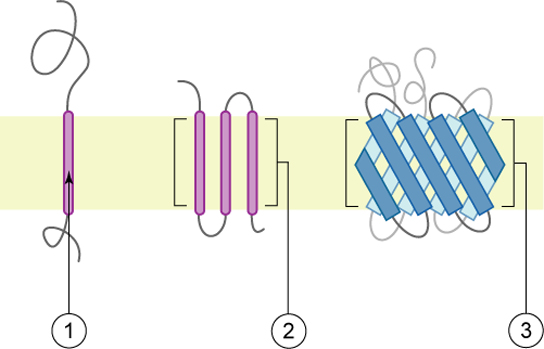

Proteins make up the second major component of plasma membranes. Integral proteins (some specialized types are called integrins) are, as their name suggests, integrated completely into the membrane structure, and their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interact with the hydrophobic region of the the phospholipid bilayer. Single-pass integral membrane proteins usually have a hydrophobic transmembrane segment that consists of 20–25 amino acids. Some span only part of the membrane—associating with a single layer—while others stretch from one side of the membrane to the other, and are exposed on either side. Some complex proteins are composed of up to 12 segments of a single protein, which are extensively folded and embedded in the membrane. This type of protein has a hydrophilic region or regions, and one or several mildly hydrophobic regions. This arrangement of regions of the protein tends to orient the protein alongside the phospholipids, with the hydrophobic region of the protein adjacent to the tails of the phospholipids and the hydrophilic region or regions of the protein protruding from the membrane and in contact with the cytosol or extracellular fluid.

Carbohydrates are the third major component of plasma membranes. They are always found on the exterior surface of cells and are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins) or to lipids (forming glycolipids). These carbohydrate chains may consist of 2–60 monosaccharide units and can be either straight or branched. Along with peripheral proteins, carbohydrates form specialized sites on the cell surface that allow cells to recognize each other. This recognition function is very important to cells, as it allows the immune system to differentiate between body cells (called “self”) and foreign cells or tissues (called “non-self”). Similar types of glycoproteins and glycolipids are found on the surfaces of viruses and may change frequently, preventing immune cells from recognizing and attacking them. These carbohydrates on the exterior surface of the cell—the carbohydrate components of both glycoproteins and glycolipids—are collectively referred to as the glycocalyx (meaning “sugar coating”). The glycocalyx is highly hydrophilic and attracts large amounts of water to the surface of the cell. This aids in the interaction of the cell with its watery environment and in the cell’s ability to obtain substances dissolved in the water.

Key Points

- The main fabric of the membrane is composed of amphiphilic or dual-loving, phospholipid molecules.

- Integral proteins, the second major component of plasma membranes, are integrated completely into the membrane structure with their hydrophobic membrane-spanning regions interacting with the hydrophobic region of the phospholipid bilayer.

- Carbohydrates, the third major component of plasma membranes, are always found on the exterior surface of cells where they are bound either to proteins (forming glycoproteins ) or to lipids (forming glycolipids).

Key Terms

- amphiphilic: Having one surface consisting of hydrophilic amino acids and the opposite surface consisting of hydrophobic (or lipophilic) ones.

- hydrophilic: Having an affinity for water; able to absorb, or be wetted by water, “water-loving.”

- hydrophobic: Lacking an affinity for water; unable to absorb, or be wetted by water, “water-fearing.”