8.10: Synapsis and Invasion of Single Strands

- Page ID

- 362

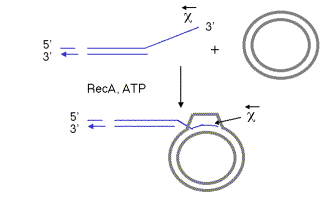

The pairing of the two recombining DNA molecules (synapsis) and invasion of a single strand from the initiating duplex into the other duplex are both catalyzed by the multi-functional protein RecA. This invasion of the duplex DNA by a single stranded DNA results in the replacement of one of the strands of the original duplex with the invading strand, and the replaced strand is displaced from the duplex. Hence this reaction can also be called strand assimilation or strand exchange. RecA has many activities, including stimulating the protease function of LexA and UmuD (see Chapter 7), binding to and coating single-stranded DNA, stimulating homologous pairing between single-stranded and duplex DNA, assimilating single-stranded DNA into a duplex, and catalyzing the hydrolysis of ATP in the presence of DNA (i.e. it is a DNA-dependent ATPase). It is required in all 3 pathways for recombination. For instance, the DNA molecule with a single-stranded 3’ end generated by the RecBCD enzyme can be assimilated into a homologous region of another duplex, catalyzed by RecA and requiring the hydrolysis of ATP (Figure 8.14).

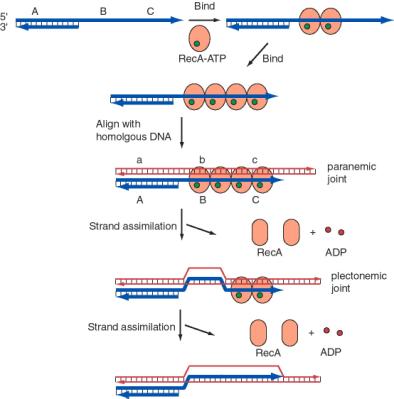

The process of single-strand assimilation occurs in three steps, as illustrated in Figure 8.15. First, RecA polymerizes onto single-stranded DNA in the presence of ATP to form the presynaptic filament. The single strand of DNA lies within a deep groove of the RecA protein, and many RecA-ATP molecules coat the single-stranded DNA. One molecule of the RecA protein covers 3 to 5 nucleotides of single-stranded DNA. The nucleotides are extended axially so they are about 5 Angstroms apart in the single-stranded DNA, about 1.5 times longer than in the absence of RecA-ATP.

Next, the presynaptic filament aligns with homologous regions in the duplex DNA. A substantial length of the three strands are held together by a polumer of RecA-ATP molecules. The aligned duplex and single strand forms a paranemic joint, meaning that the single strand is not intertwined with the double strand at this point. The duplex DNA, like the single-stranded DNA, is extended to about 1.5 times longer than in normal B form DNA (18.6 bp per turn). This extension is thought to be important in homologous pairing.

Finally, the strands are exchanged from to form a plectonemic joint. In this stage, the invading single strand is now intertwined with the complementary strand in the duplex, and one strand of the invaded duplex is now displaced. In E. coli, exchange occurs in a 5' to 3' direction relative to the single strand and requires ATP hydrolysis. In contrast, the yeast homolog, Rad51, causes the single-strand to invade with the opposite polarity, i.e. 3' to 5'. Thus the direction of this polarity is not a universally conserved feature of recombination mechanisms.

The product of strand assimilation is a heteroduplex in which one strand of the duplex was the original single-stranded DNA. The other strand of the original duplex is displaced.

Many details of the activity of RecA have been revealed by in vitroassays for single strand assimilation, or strand exchange. The DNA substrates for strand exchange catalyzed by RecA must meet three requirements. There must be a region of single stranded DNA on which RecA can bind and polymerize, the two molecules undergoing strand exchange must have a region of homology, and there must be a afree end within the region of homology. The latter requirement can be overcome by providing a topoisomerase.

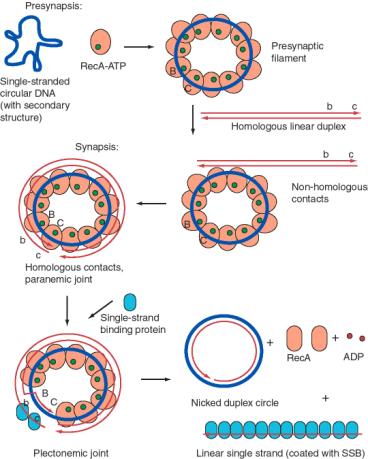

One such assay is the conversion of a single-stranded circular DNA to a duplex circle (Figure 8.16). The substrates for this reaction are a circular single-stranded DNA and a homologous linear duplex. These are mixed together in the presence of RecA and ATP. Many RecA-ATP molecules coat the single-stranded circle to form the nucleoprotein presynaptic filament, as discussed above. During synapsis, annealing is initiated with the 3' end of the strand complementary to the single-stranded circle. Thus the single strand invades with 5' to 3' polarity (with reference to its own polarity). Strand displacement, driven by ATP hydrolysis to dissociate the RecA, results in the formation of a nicked circle (one strand of which was the original single-stranded circle) and a linear single strand of DNA.

Exercise

Try to relate this in vitro assay to the steps in the double-strand-break model for recombination. What step(s) in the model does this mimic? What else is needed for to get to the recombinant joints (Holliday junctions)?

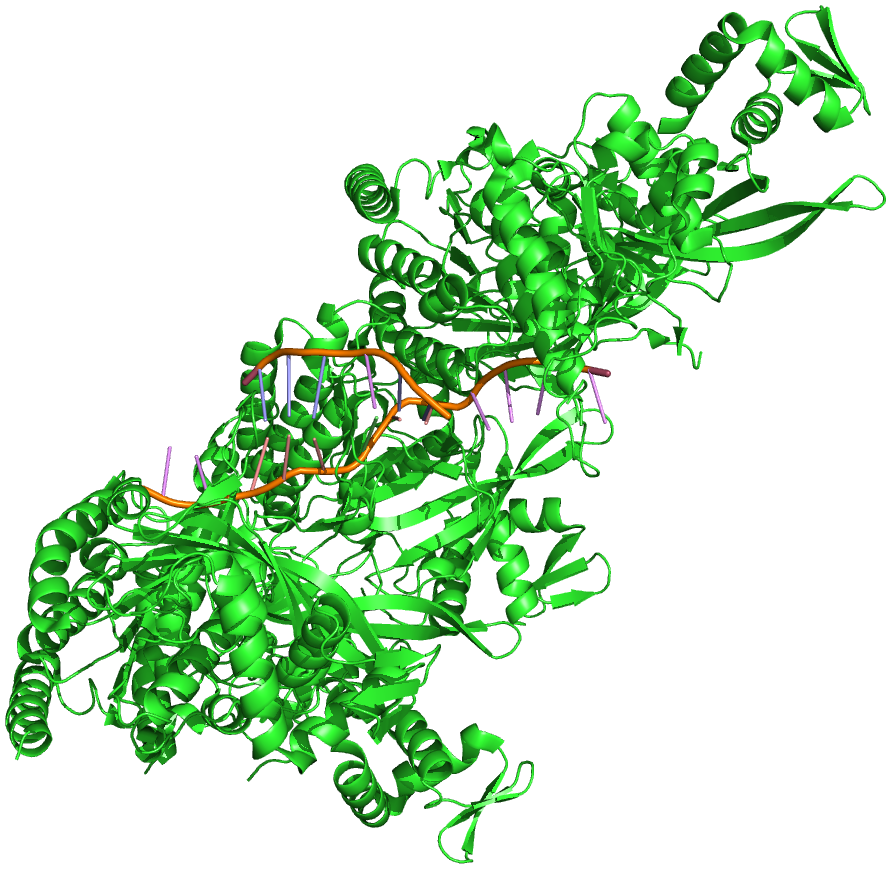

The structure of E. coliRecA bound by ADP, both monomer and polymer, have been solved by X-ray crystallography. As shown in Figure 8.17, the central domain has the binding site for ATP and ADP, and is presumably the site of binding of the single-stranded and double-stranded DNA. The domains extending away from the central region are involved in polymerization of RecA proteins and in interactions between the presynaptic fibers.

Proteins homologous to the E. coli RecA are found in yeast (Rad51 and Dmc1) and in mice (Rad51). Given the universality of recombination, it is likely that homologs will be found in virtually all species. Mutations in the E. coli recA gene reduce conjugational recombination by as much as 10,000 fold, so it is clear that RecA plays a central role in recombination. However, null mutations in recA are not lethal, nor are null mutations in the yeast homologs RAD51 and DMC1. In contrast, mice homozygous for a knockout mutation in the Rad51 gene die very early in development, at the 4-cell stage. This indicates that in mice, this RecA homolog is playing a novel role in replication or repair, presumably in addition to its role in recombination.