2.6.2.1: Cycads and Ginkos

- Page ID

- 37020

Learning Objectives

- Use morphological characteristics and life history traits to distinguish between ginkgos and flowering plants.

- Explain why Ginkgo biloba is called a living fossil.

- Use morphological characteristics and life history traits to distinguish between cycads and ferns.

- Define the term dioecious and provide an example.

Ginkgophyta

As of 2019, the most recent genetic studies have placed ginkgos as the oldest of the extant gymnosperms. This does not mean that it was the first gymnosperm. From the fossil record, it seems that most early gymnosperms went extinct. The sole remaining species in this group, Ginkgo biloba, is a living fossil virtually unchanged from its fossilized ancestors (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). This plant is almost extinct in the wild--a few natural populations remain in China--but has a wide distribution as an ornamental tree. It is possible that this species was only kept alive due to cultivation efforts by Buddhist monks for its medicinal properties.

Ginkgo biloba is dioecious (as an exception among plants, Ginkgo has sexual chromosomes like birds and mammals) and the pollen is transported by wind to ovulate trees. The microstrobili are reminiscent of the catkins produced on some flowering plants (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Pollen grains of ginkgos produce two multi-flagellate spermatozoa.

Ovulate have paired ovules at the tips of branches that look much like fruits (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The fleshy coating of the seed emits a foul odor as it decays, making staminate trees a more popular choice in ornamental settings.

This species is also long-lived, a single tree can live for thousands of years (the oldest is 3,500 years old!), and they are resistant to most pests. This pest resistance, as well as the medicinal properties, can be attributed to a wide variety of secondary metabolites produced in the leaves, including terpenes and flavonoids. A ginkgo tree at the Zenpuku temple in Tokyo, Japan is approximately 750 years old (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Ginkgos were the first plants to regenerate after the Hiroshima bombing and were not found to contain any genetic abnormalities.

Cycadophyta

Although seed ferns are now extinct, some of their living descendants, the cycads, resemble them closely (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). Cycads are one of the more ancient gymnosperm lineages, appearing in the fossil record around 300 million years ago. Similar to Ginkgo biloba, cycads have sperm with multiple flagella that swim toward the egg. For plants, this is considered an ancestral trait. Cycads and ginkgos emerge as sister taxa that are ancestral to the conifers.

Cycads produce leaves that are large and pinnately compound (have leaflets arising from a central axis, like a feather), making them appear frond-like. Unlike ferns, but like other gymnosperms, these leaves are xerophytic (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)): tough, waxy, and more resistant to desiccation.

Cycads are dioecious. The microstrobilus is produced on the "male" plant and consists of many microsporophylls bearing microsporangia. It is called a microstrobilus, not because it is small (these can be over a meter in height), but because the it produces smaller and more numerous spores than the megasporangium. Microstrobili are often larger than megastrobili in cycads (see Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) and Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). In cycads, pollen is carried to the megastrobilus by insects. The megastrobilus is produced on the "female" plant, and is composed of overlapping megasporophylls. In some cycads, such as Cycas spp., the megasporophylls do not form into a strobilus structure. Ovules are produced on megasporophylls (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)); these ovules will develop into seeds after fertilization. Seeds are then dispersed by animals.

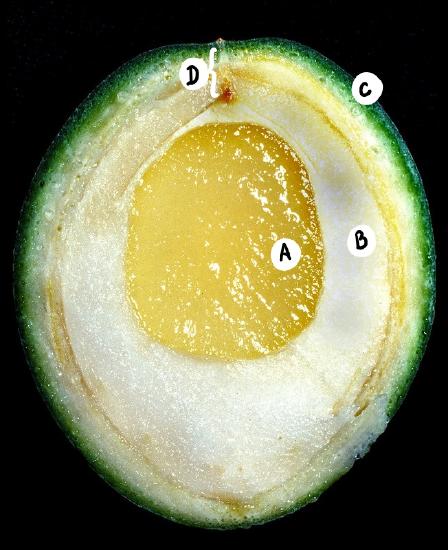

Descriptive text for the second image: The megagametophyte is gelatinous looking and at the center, connected to the exterior by the micropyle. The megagametophyte is surrounded by a pithy-looking nucellus, which is encased by a rind-like integument.

Attribution

Curated and authored by Maria Morrow, CC-BY-NC, using 7.6 Spermatophyta – Seed Plants from Introduction to Botany by Alexey Shipunov (public domain)