2.5.2.2: Marchantiophyta

- Page ID

- 37010

Learning Objectives

- Use morphological traits and cellular components to distinguish between liverworts and other bryophytes.

- Identify structures and phases in the Marchantia life cycle; know their ploidy.

Liverworts, Phylum Marchantiophyta

The liverworts, formerly the Hepatophyta, got their name from their thalloid gametophytes being compared to the shape of a liver. However, many liverworts produce leafy gametophytes. This group is often presented as a basal lineage of bryophytes due to the lack of stomata present in either stage of the life cycle (among other traits). However, recent genetic evidence does not support this and instead places mosses and liverworts as sister taxa. Liverworts have a global distribution and can be found in many habitats, including a few desert and even arctic species. There are around 5,000 described species of liverworts, though estimates put this at about half of the actual number of species. The type genus for this group, Marchantia, is a common invader of greenhouses and potted plants.

Gametophyte Morphology

There are two distinct type of liverwort gametophytes: leafy liverworts and thalloid liverworts. Leafy liverworts have leaves (though not true leaves, as they lack vascular tissue) without a central costa, which you will see in mosses. The leaves are arranged in a flat plane (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) with a set of smaller underleaves (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Thalloid liverworts have no leaves and their gametophytes look more similar to hornwort gametophytes. Another similarity to hornworts is the presence of simple pores for gas exchange (no guard cells, meaning pores are permanently open). Unlike hornworts, liverwort cells have multiple chloroplasts. Rhizoids in this group are unicellular. Asexual clones, called gemmae (sing. gemma), are sometimes produced in structures called gemmae cups (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). These are haploid and genetically identical to the parent thallus.

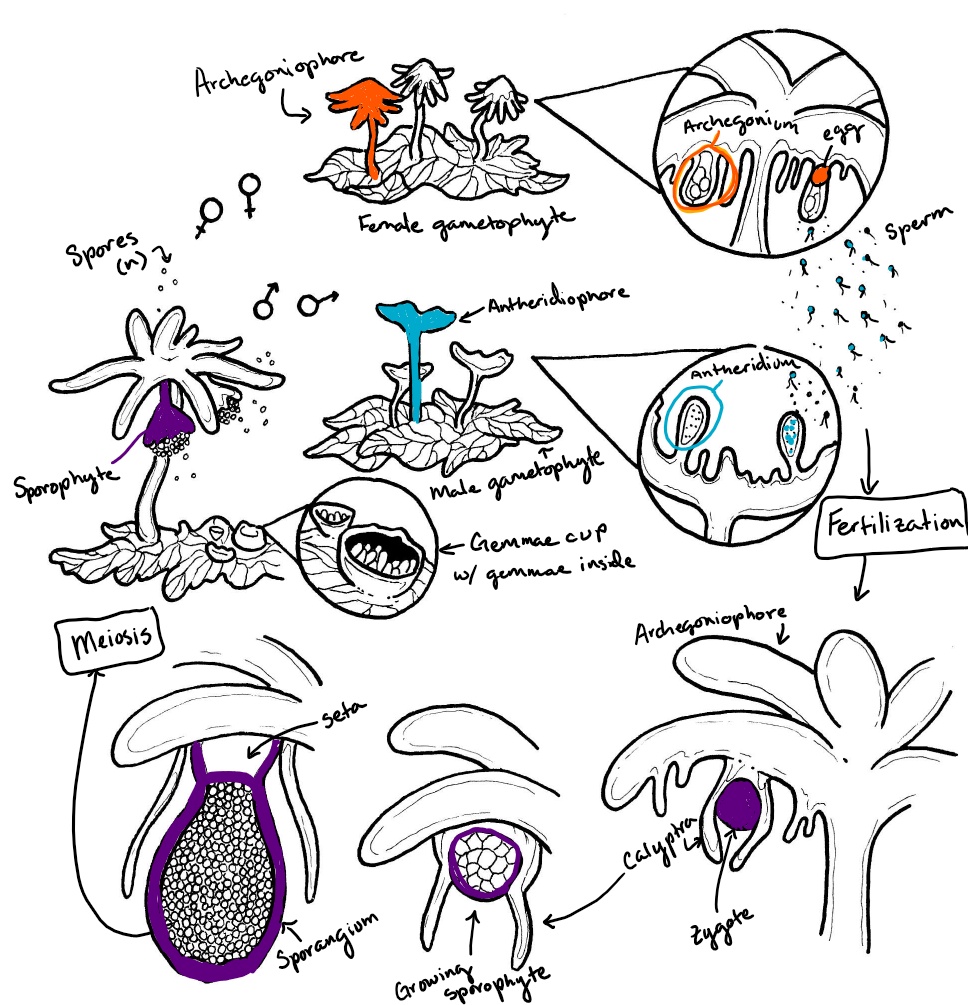

The thalloid liverwort Marchantia has complex reproductive structures. Palm tree-like structures called archegoniophores are formed from the haploid gametophyte tissue. Archegonia are produced on the underside of the extending arms. When fertilized, the sporophyte will grow within the archegonium and emerge on the underside of the archegoniophore (see the right side of Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The antheridia are produced in a separate stalked structure with a flat top called an antheridiophore (see the left side of Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Water droplets splash onto the flat top, dispersing flagellated spores from the embedded antheridia.

Sporophyte Morphology

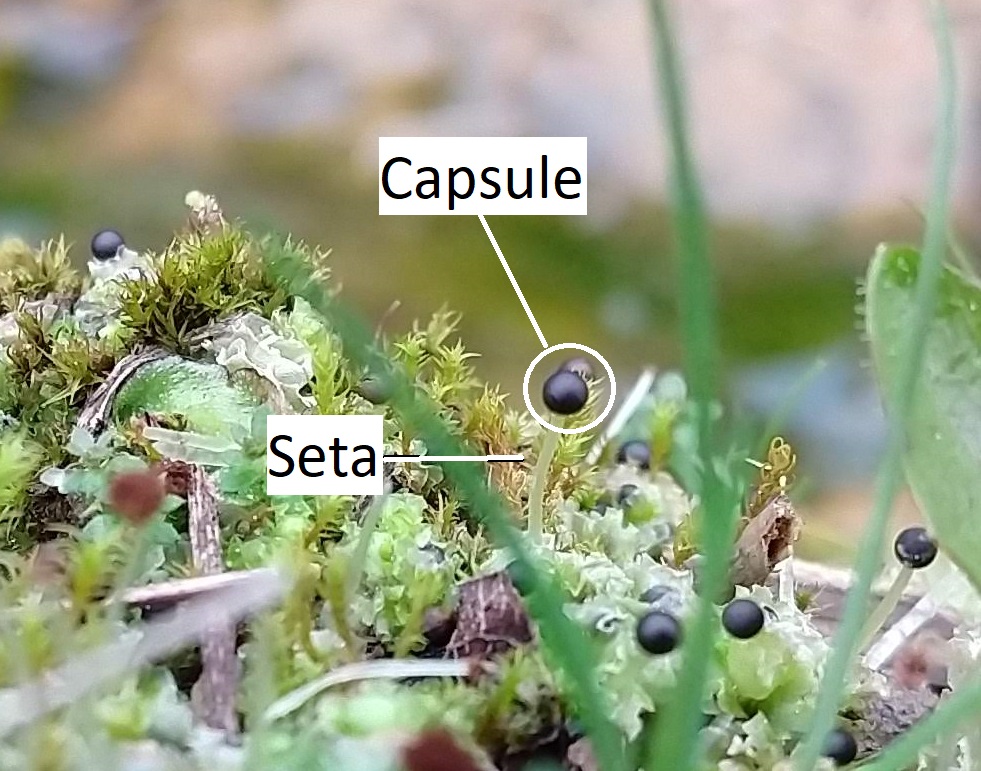

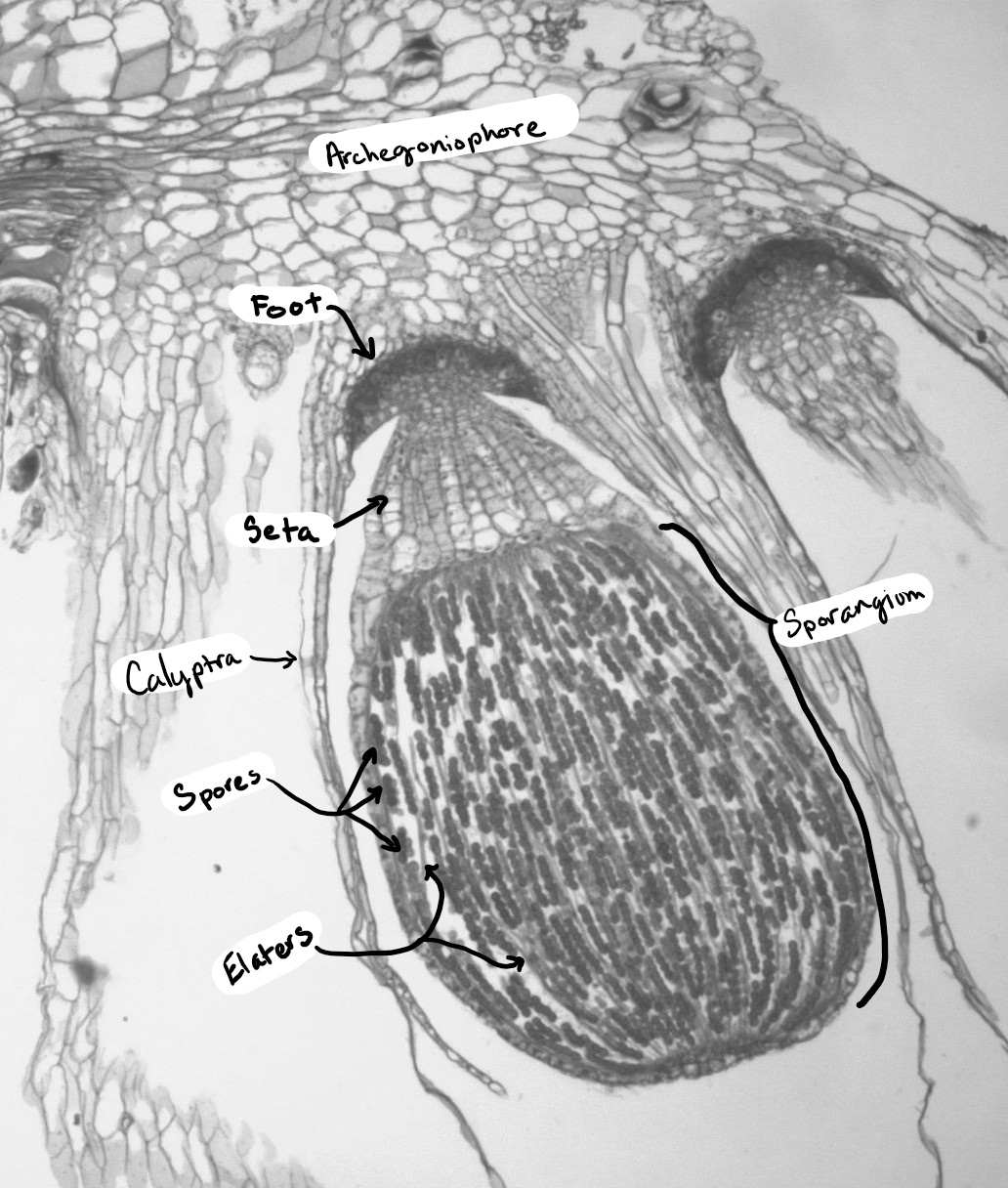

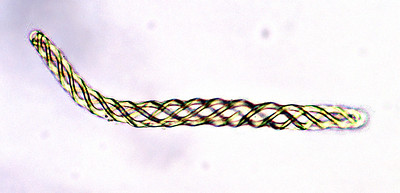

Liverworts produce a single sporangium (also called a capsule) at the end of a seta, which is often fragile and transparent (Figure \(\PageIndex{5-6}\)). The seta does not elongate until after the sporangium has formed. The sporangium dehisces, splitting into four valves (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). In thalloid liverworts, the sporophyte may emerge directly from the thallus or, as is the case with the genus Marchantia, from under archegoniophores. In leafy liverworts, the sporophyte often emerges laterally from the thallus. Within the sporangium, there are elaters (true unicellular elaters, Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) that aid in spore dispersal. Unlike the hornworts, there is no columella. Unlike the mosses, the capsule lacks an operculum.

Marchantia Life Cycle

Marchantia polymorpha is a thalloid liverwort with a complex life cycle (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Asexual reproduction is accomplished through the production of haploid gemmae from the gametophyte thallus. Sexual reproduction occurs from dioecious gametophytes: archegoniophores and antheridiophores are produced on separate gametophytes. Sperm splashed from the antheridial head swim through the water with their dual flagella to reach an egg at the base of an archegonium. These archegonia are situated on the underside of the archegonial head. The diploid zygote grows within the archegonium, surrounded by its remaining tissue (the calyptra). As the sporangium develops, meiosis occurs simultaneously to produce haploid spores. A short seta extends to push the developed sporangium outward, lifting the arms of the archegoniophore. The sporangium dehisces into four valves, exposing the elaters to the external environment where they rapidly twist, flinging the haploid spores into the air. These haploid spores can germinate and grow into male or female gametophytes.

Content by Maria Morrow, CC-BY-NC