1.2: Microscopy

- Page ID

- 24728

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Light Microscope

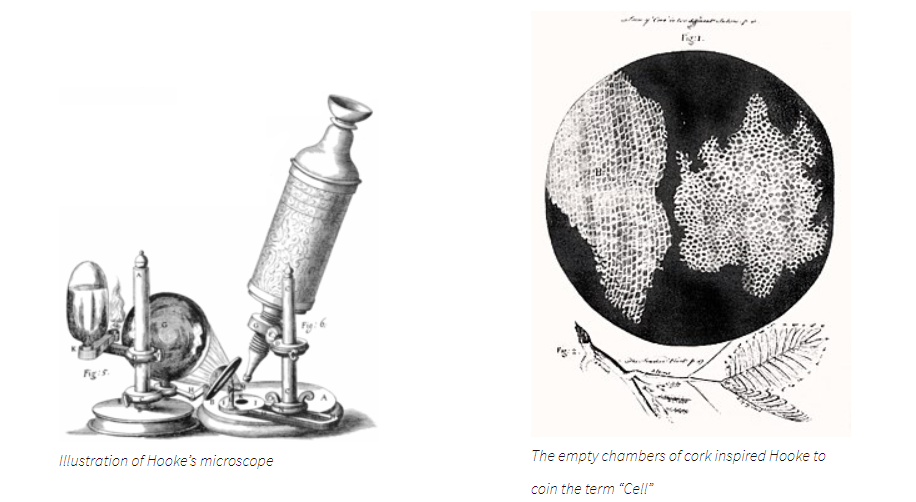

Hooke’s Cell

In 1665, Robert Hooke published Micrographia, a book that illustrated highly magnified items that included insects and plants. This book spurred on interest in the sciences to examine the microscopic world using lenses but is also notable for Hooke’s observations of cork where he used the word “cell” in a biological sense for the first time.

The Father of Microbiology: van Leeuwenhoek

The Dutch tradesman Antonie van Leeuwenhoek used high power magnifying lenses to examine the parts of insects and to examine the quality of fabric in his drapery business. He began to experiment with pulling glass to generate lenses and developed a simple microscope to observe samples. Using a simple single lens with a specimen mounted on a point, he was able to identify the first microscopic “animalcules” (little animals) that will be later known as protozoa (original animals).

The Dutch tradesman Antonie van Leeuwenhoek used high power magnifying lenses to examine the parts of insects and to examine the quality of fabric in his drapery business. He began to experiment with pulling glass to generate lenses and developed a simple microscope to observe samples. Using a simple single lens with a specimen mounted on a point, he was able to identify the first microscopic “animalcules” (little animals) that will be later known as protozoa (original animals).

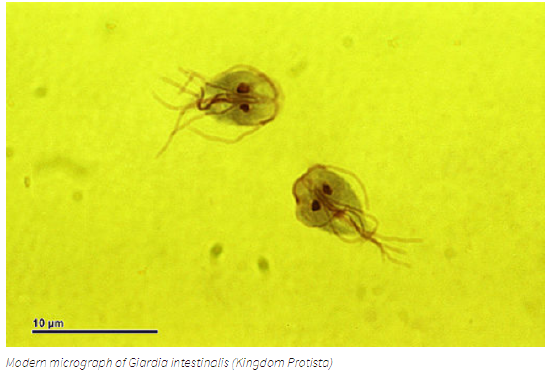

Though van Leeuwenhoek’s apparatus was simple, the magnifying power of his lenses and his curiosity enabled him to perform great scientific observations on the microscopic world. He was ridiculed for fabricating his observations of protists at first. Ever the scientist, van Leeuwenhoek examined samples of his own diarrhea to discover Giardia intestinalis. While he did not make the connection of the causative nature of this microorganism, he described the details of the way this organism could propel itself through the medium in great detail.

Modern Compound Microscope

Unlike van Leeuwenhoek’s single-lens microscope, we now combine the magnifying power of multiple lenses in what is called a compound microscope.

- Ocular lens or eyepiece

- Nose Piece/ Lens Carousel

- Objective lens

- Course Focus Knob

- Fine Focus Knob

- Stage

- Lamp

- Condenser

- Stage control

Using the Light Microscope

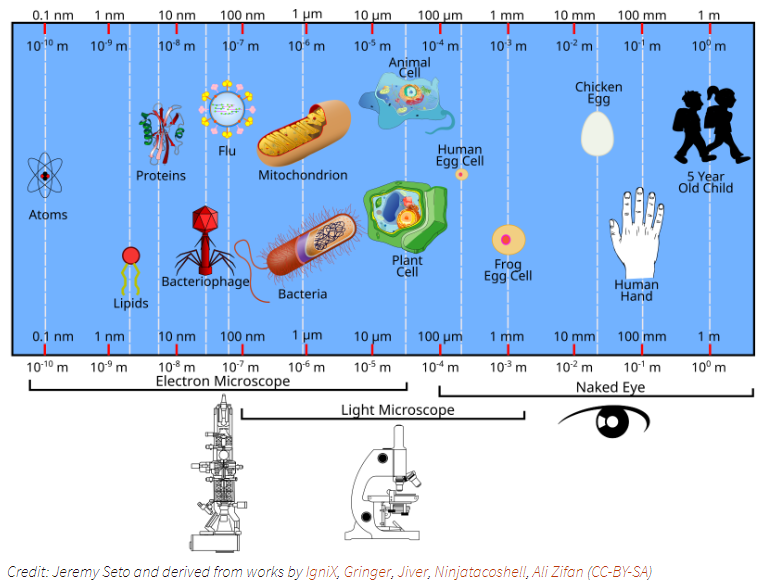

Microscopic World

Scale

Magnification

Magnification is the process of enlarging the appearance of an object. We calculate the magnification of an object by indicating the fold change in size. So if something appears to be double the size of the real item, then it is obviously magnified 2X. Because there is a magnification by the eye-piece (ocular lens), as well as the objective lenses, our final magnification of an item is the product of those two lenses.

The lowest magnification objective lens (usually 4X or 5X) is referred to as a scanning lens. There is also usually a low power lens at 10X and a higher magnification lens at 40X. There may be a higher magnification lens at 100X but these usually require oil to function properly and are often reserved for microbiology labs.

- What is the power of the ocular lens?

- We can calculate that as:

Magnificationtotal = Magnificationobjective X Magnificationocular - With this in mind, fill in the following table:

Field of View (FOV)

In a microscope, we ordinarily observe things within a circular space (or field) as defined by the lenses. We refer to this observable area as the field of view (FOV). Understanding the size of the FOV is important because actual sizes of the object can be calculated using the Magnification of the lenses.

FOV can be described as the area of a circle:

What are the effects of magnification on FOV?

In image 1, we can see a model of DNA on a table with a water bottle and a large area of the room. Image 2 displays less of the room in the background but the DNA model is larger in appearance because the magnification is greater. In image 3, we no longer see evidence of a door and the DNA model is much larger than before. In image 4, we no longer see the table the model and water bottle rest upon. While the last image is largest, we see less of the surrounding objects. We have higher magnification at the cost of the field of view. FOV is inversely related to the magnification level.

Field of View Calculation

- Examine a ruler under scanning magnification

- Measure the diameter in mm.

- Diameter= _________________

- Radius= ____________________

- Calculate the field of view at this magnification= __________________

- Examine a ruler under low magnification (10x)

- Measure the diameter in mm.

- Diameter= _________________

- Radius= ____________________

- Calculate the field of view at this magnification= ____________________

- What is the relationship in the between the magnification and field of view?_______________________________________________________________________________

- What is the proportion of change in the field of view when doubling the magnification?______________________________________________________________________

The Letter “e”

- Orient a slide with the Letter “e” so that it is read as an “e” without magnification

- Draw the “e” at scanning, low and high magnification

Depth of Field

1. Examine the slide of colored threads under scanning power so the cross-point of the threads is at the center of the field.

2. Raise the magnification to the low power objective

- What do we notice about the threads and the focus?

- How can we explain this observation with respect to the threads?

- Close the diaphragm so allow a pinpoint of light through the slide. What effect does this have on the image?

We notice that when we observe 3 overlapping threads of different color under a microscope, we can focus on one thread at a time. Similarly, when we zoom in a great deal on the DNA model below, we notice that the print on the water bottle is not sharp.

Highest Magnification with shallow depth of field. Notice how the label on the water bottle is blurry while the lettering on the DNA model is sharp.

We know that the water bottle is behind the DNA molecule. Under the microscope, the threads of differing color are also stacked on top of each other. We recognize that they are on different planes because they are three dimensional. Each thread has depth and does not occupy the same exact space. If we focus on the print of the water bottle on the image above, we would no longer see the lettering on the DNA molecule sharply. We refer to this concept as Depth of Field (DOF). Under the microscope, at low magnification, we can make out fewer finer details. However, most items appear on the same plane in this case and or comparably sharp. But as we increase the magnification and see finer details, the distances between the various planes in view become more apparent. We can see a similar phenomenon at low magnification of the DNA model. At the low magnification, we may not be able to read the print on the water bottle, but the bottle and DNA molecule are of a similar distance from our view that the small difference in apparent depth is not as noticeable. We can still draw on other visual cues to know that the bottle is behind the model, but the sharpness of both items are equivalent.

Examining Cells

- Choose a prepared slide of a Protist (Euglena, Amoeba, Paramecium)

- Prepare a wet mount of a drop of pond water and place a coverslip over the drop.

- Swab the inside of your cheek

- Roll the swab across a slide

- Drop some methylene blue onto the slide

- Place a coverslip over the drop

- Visualize and draw your cheek cells

- Document your observations by drawing the cells and by using your phone to snap an image.

Real Biological Examples

We can see the concepts of FOV and DOF in the following pictures.

In an even more extreme close-up (higher magnification), we would have difficulty focusing on both the eyes and beak since there is depth and distance between those features.

How Do We Use Microscopes

In our lab, we look at some pond water. What do we see? Why is this significant? How does the microscope help us study these items? What is the utility of the concepts of magnification, FOV, and DOF when we use microscopes to study biological samples?