7.3: Breathing

- Page ID

- 92698

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The swimmer in this photo is doing the butterfly stroke. This swimming style requires the swimmer to carefully control his breathing so it is coordinated with his swimming movements. Breathing is the process of moving air into and out of the lungs, which are the organs in which gas exchange takes place between the atmosphere and the body. Breathing is also called ventilation, and it is one of two parts of the life-sustaining process of respiration, the other part being gas exchange. Before you can understand how breathing is controlled, you need to know how breathing occurs.

How Breathing Occurs

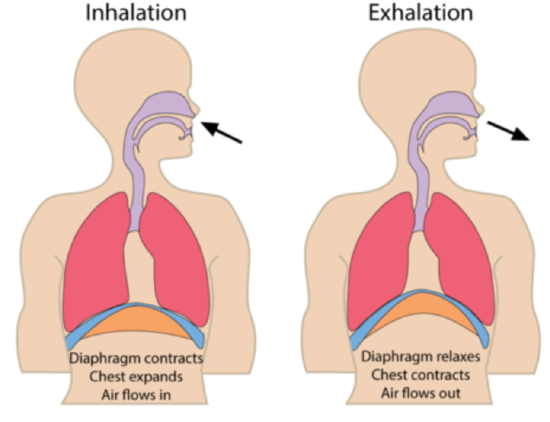

Breathing is a two-step process that includes drawing air into the lungs, or inhaling, and letting the air out of the lungs, or exhaling. Both processes are illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Inhaling

Inhaling is an active process that results mainly from the contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). The diaphragm is a large, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs that separates the thoracic (chest) and abdominal cavities. When the diaphragm contracts, the thoracic cavity expands and the contents of the abdomen are pushed downward. Other muscles, such as external intercostal muscles between the ribs, also contribute to the process of inhalation, especially when inhalation is forced, as when taking a deep breath. These muscles help increase thoracic volume by expanding the ribs outward. With the chest expanded, there is lower air pressure inside the lungs than outside the body, so outside air flows into the lungs via the respiratory tract.

Exhaling

Exhaling involves the opposite series of events. The diaphragm relaxes, so it moves upward and decreases the volume of the thorax ( Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). Air pressure inside the lungs increases so it is higher than the air pressure outside the lungs. Exhaling, unlike inhaling, is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs. With the change in air pressure, the lungs contract to their pre-inflated size, forcing out the air they contain in the process. Air flows out of the lungs, similar to the way air rushes out of a balloon when it is released. If exhalation is forced, internal intercostal and abdominal muscles may help move the air out of the lungs.

Control of Breathing

Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously as well as unconsciously. Think about using your breath to blow up a balloon. You take a long, deep breath, and then you exhale the air as forcibly as you can into the balloon. Both the inhalation and exhalation are consciously controlled.

Conscious Control of Breathing

You can control your breathing by holding your breath, slowing your breathing, or hyperventilating, which is breathing more quickly and shallowly than necessary. You can also exhale or inhale more forcefully or deeply than usual. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities besides blowing up balloons, including swimming, speech training, singing, playing many different musical instruments ( Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), and doing yoga, to name just a few.

There are limits on the conscious control of breathing. For example, it is not possible for a healthy person to voluntarily stop breathing indefinitely. Before long, there is an irrepressible urge to breathe. If you were able to stop breathing for a long enough time, you would lose consciousness. The same thing would happen if you were to hyperventilate for too long. Once you lose consciousness so you can no longer exert conscious control over your breathing, involuntary control of breathing takes over.

Unconscious Control of Breathing

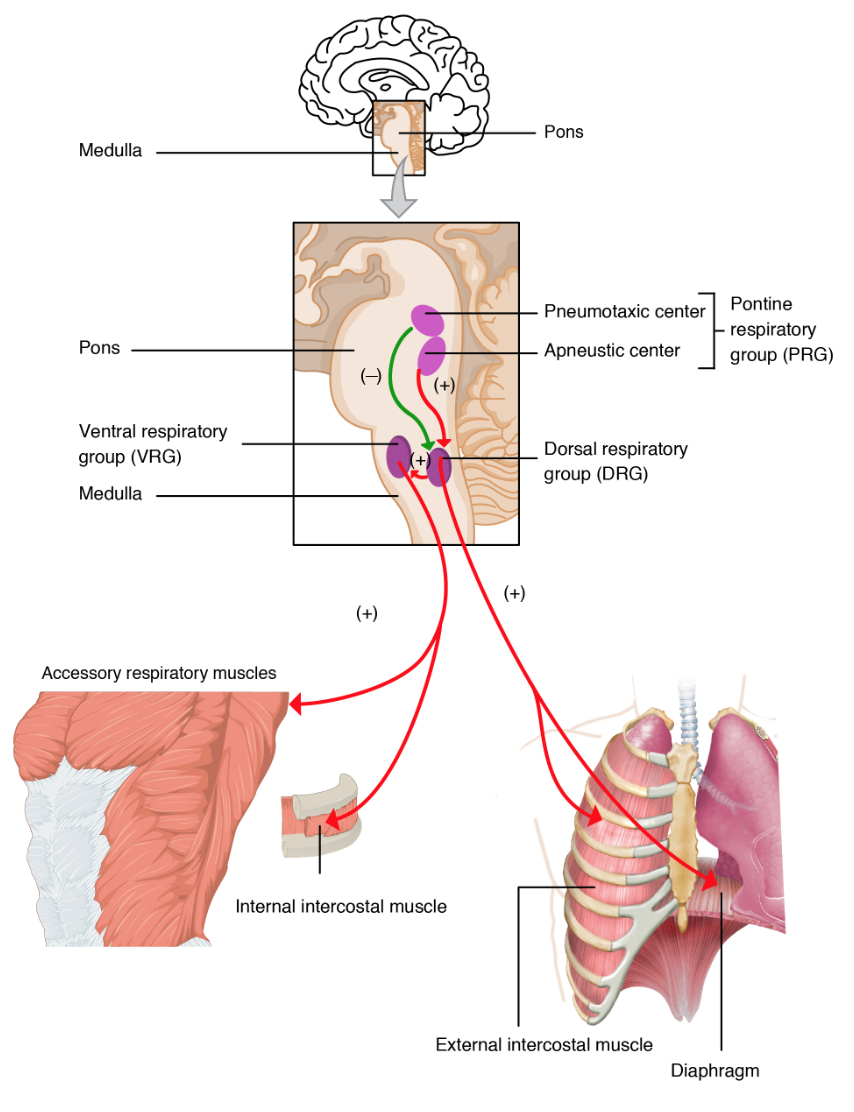

Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem ( Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The respiratory centers automatically and continuously regulate the rate of breathing depending on the body’s needs. These are determined mainly by blood acidity or pH. When you exercise, for example, carbon dioxide levels increase in the blood because of increased cellular respiration by muscle cells. The carbon dioxide reacts with water in the blood to produce carbonic acid, making the blood more acidic, so pH falls. The drop in pH is detected by chemoreceptors in the medulla. Blood levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide, in addition to pH, are also detected by chemoreceptors in major arteries, which send the “data” to the respiratory centers. The respiratory center responds by sending nerve impulses to the diaphragm, “telling” it to contract more quickly so the rate of breathing speeds up. With faster breathing, more carbon dioxide is released into the air from the blood, and blood pH returns to the normal range.

The opposite events occur when the level of carbon dioxide in the blood becomes too low and blood pH rises. This may occur with involuntary hyperventilation, which can happen in panic attacks, episodes of severe pain, asthma attacks, and many other situations. When you hyperventilate, you blow off a lot of carbon dioxide, leading to a drop in blood levels of carbon dioxide. The blood becomes more basic (alkaline), causing its pH to rise.

Nasal vs. Mouth Breathing

Nasal breathing is breathing through the nose rather than the mouth, and it is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing. The hair-lined nasal passages do a better job of filtering particles out of the air before it moves deeper into the respiratory tract. The nasal passages are also better at warning and moistening the air, so nasal breathing is especially advantageous in the winter when the air is cold and dry. In addition, the smaller diameter of the nasal passages creates greater pressure in the lungs during exhalation. This slows the emptying of the lungs, giving them more time to extract oxygen from the air.

Drowning is defined as respiratory impairment from being in or under a liquid. It is further classified according to its outcome into death, ongoing health problems, or no ongoing health problems (full recovery). In the United States, accidental drowning is the second leading cause of death (after motor vehicle crashes) in children aged 12 years and younger. There are some potentially dangerous myths about drowning. Knowing what they are might save your life or the life of a loved one, especially a child.

Myth: People drown when they aspirate water into their lungs.

Reality: Generally, in the early stages of drowning, very little water enters the lungs. A small amount of water entering the trachea causes a muscular spasm in the larynx that seals the airway and prevents the passage of water into the lungs. This spasm is likely to last until unconsciousness occurs.

Myth: You can tell when someone is drowning because they will shout for help and wave their arms to attract attention.

Reality: The muscular spasm that seals the airway prevents the passage of air as well as water, so a person who is drowning is unable to shout or call for help. In addition, instinctive reactions that occur in the final minute or so before a drowning person sinks under the water may look similar to calm, safe behavior. The head is likely to be low in the water, tilted back with the mouth open. The person may have uncontrolled movements of the arms and legs, but they are unlikely to be visible above the water.

Myth: It is too late to save a person who is unconscious in the water.

Reality: An unconscious person rescued with an airway still sealed from the muscular spasm of the larynx stands a good chance of full recovery if they start receiving CPR within minutes. Without water in the lungs, CPR is much more effective. Even if the cardiac arrest has occurred so the heart is no longer beating, there is still a chance of recovery. However, the longer the brain goes without oxygen, the more likely brain cells will die. Brain death is likely after about six minutes without oxygen, except in exceptional circumstances, such as young people drowning in very cold water. There are examples of children surviving, apparently without lasting ill effects, for as long as an hour in cold water (see Explore More below for an example). Therefore, rescuers retrieving a child from cold water should attempt resuscitation even after a protracted period of immersion.

Myth: If someone is drowning, you should start administering CPR immediately, even before you try to get the person out of the water.

Reality: Removing a drowning person from the water is the first priority because CPR is ineffective in the water. The goal should be to bring the person to stable ground as quickly as possible and then to start CPR.

Myth: You are unlikely to drown unless you are in water over your head.

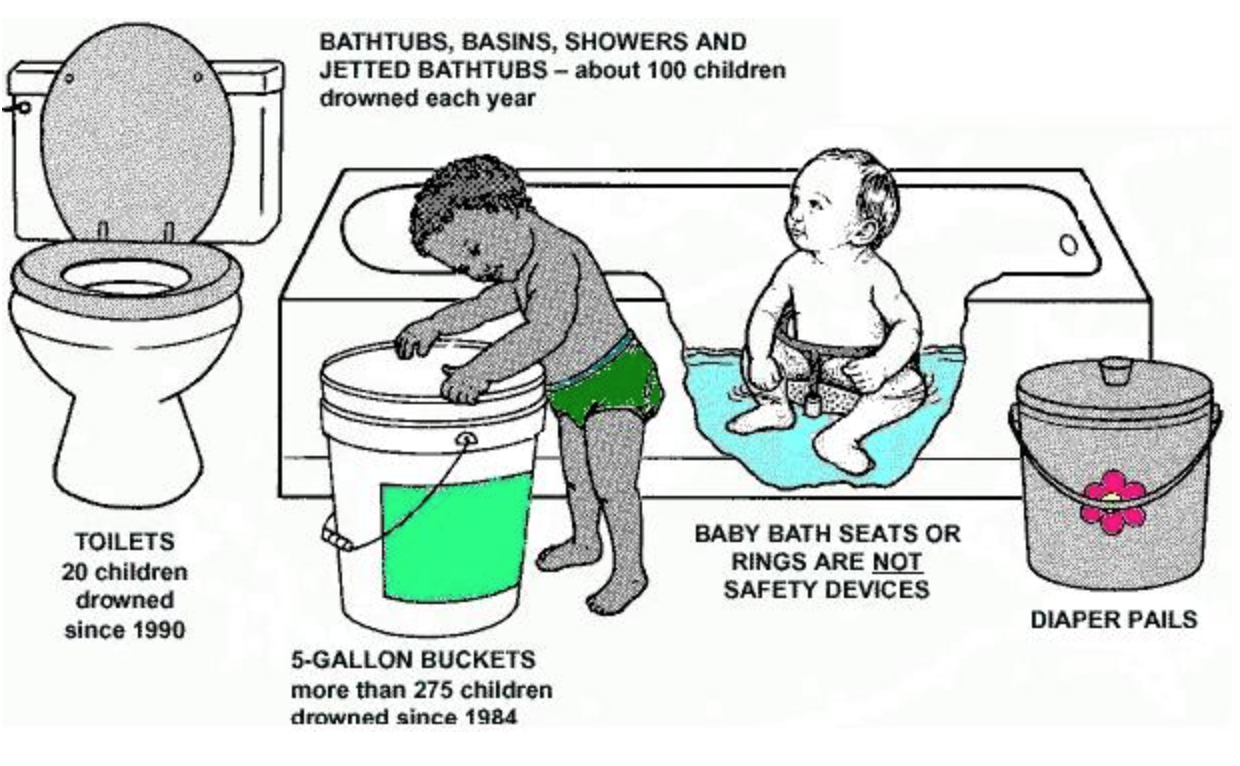

Reality: Depending on circumstances, people have drowned in as little as 30 mm (about 1 ½ in.) of water. For example, inebriated people or those under the influence of drugs have been known to have drowned in puddles. Hundreds of children have drowned in the water in toilets, bathtubs, basins, showers, pails, and buckets (see figure below).

Review

- Define breathing.

- What is another term for the process of breathing?

- What is the main difference between the processes of inhaling and exhaling?

- Give examples of activities in which breathing is consciously controlled.

- Young children sometimes threaten to hold their breath until they get something they want. Why is this an idle threat?

- Explain how unconscious breathing is controlled.

- Why is nasal breathing generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing?

- For each of the following, indicate whether it occurs during the process of inhalation (I) or exhalation (E).

- The diaphragm moves downward.

- The diaphragm relaxes.

- The thoracic cavity becomes smaller.

- The air pressure in the lungs is lower than outside the body.

- Give one example of a situation that would cause blood pH to rise excessively and explain why this occurs.

- Blood levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide and pH are detected by which of these:

- Mechanoreceptors

- Chemoreceptors

- Lung receptors

- Carbon receptors

- True or False. The diaphragm can contract due to conscious control.

- True or False. Hypoventilating is breathing that is fast and shallow.

Explore More

You may have heard of “miracles” in which young people survived for extended periods of time without breathing underwater and made a full recovery. How does this happen? Read the amazing story of an Italian boy who survived for 42 minutes underwater. The article explains the physiology behind the “miracle.”

Magician and stuntman extraordinaire David Blaine reportedly can hold his breath for 17 minutes underwater. In this TED talk, he explains how he manages to perform this feat:

Attributions

- Butterfly stroke by Cpl. Jasper Schwartz, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Breathing by Zachary Wilson from CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0

- Ivan Podyomov by Alexei Zoubov, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Respiratory Centers of the Brain by OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

- Drowning Situations by U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0