9.1: Introduction to lipids

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 102280

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Search Fundamentals of Biochemistry

Learning Goals (ChatGPT o3-mini, 2/2/25)

-

Define Lipids and Their Key Properties:

• Describe what lipids are, focusing on their organic nature, hydrophobicity, and solubility in organic solvents versus aqueous solutions. -

Classify Lipids Based on Structural Components:

• Distinguish between lipids that contain fatty acids and those that contain isoprenoid units, and explain the significance of each class. -

Analyze Fatty Acid Structure and Conformation:

• Explain the structure of fatty acids, including chain length, saturation, and the impact of cis (and trans) double bonds on the conformation (zig-zag vs. kinked structures) and melting points. -

Understand the Nomenclature and Stereochemistry of Fatty Acids:

• Interpret symbolic, systematic, and common names of fatty acids and explain concepts like prochirality and the stereospecific numbering (sn system) in glycerolipids. -

Connect Lipid Structure to Function in Energy Storage and Membrane Architecture:

• Discuss how the highly reduced state of fatty acids in triacylglycerols makes them excellent energy storage molecules and compare this with the structure and hydration of polysaccharides like glycogen.

• Explain how the amphiphilic nature of lipids leads to the formation of micelles and bilayers, which are critical for membrane structure and function. -

Evaluate the Diversity of Lipid Types and Their Physiological Roles:

• Describe the roles of storage lipids (triacylglycerols) versus membrane lipids (glycerophospholipids, glyceroglycolipids, and sphingolipids), and how variations in fatty acid composition (saturated vs. unsaturated) influence their physical properties and biological functions. -

Interpret the Functional Importance of Essential Fatty Acids:

• Discuss why certain fatty acids (n-6 and n-3 classes) are essential, their metabolic precursors, and their roles in health, including effects on inflammation and brain development. -

Understand Isoprenoid Lipid Biosynthesis and Function:

• Explain how isoprenoid lipids are synthesized from DMAPP and IPP, and describe the roles of key isoprenoid derivatives such as cholesterol, terpenes, and vitamins in cellular physiology. -

Relate Lipid Aggregation to Biological Function:

• Describe how fatty acids aggregate into micelles in aqueous environments, and how this self-association influences their function, including transport by fatty acid-binding proteins (e.g., albumin). -

Integrate Lipid Structural Variability with Membrane Dynamics:

• Explain how differences in lipid shape (e.g., cone-like versus cylindrical) determine their self-assembly into specific structures like micelles or bilayers and how this impacts membrane fluidity, signaling, and vesicle formation.

These goals are intended to guide your exploration of lipid biochemistry, linking the detailed molecular structure of lipids with their diverse roles in energy storage, membrane architecture, and cellular signaling.

Introduction to Lipids

(Thanks to Rebecca Roston for providing a cohesive organizational framework and image templates)

Lipids are organic molecules soluble in organic solvents, such as chloroform/methanol, but sparingly soluble in aqueous solutions. These solubility properties arise since lipids are primarily hydrophobic. One type, triglycerides, is used for energy storage since they are highly reduced and get oxidized to release energy. Their hydrophobic nature allows them to pack efficiently through self-association in an aqueous environment. Triglycerides are also used for insulation since they conduct heat poorly, which is good if you live in a cold climate but bad if you wish to dissipate heat in a hot one. Triglycerides also offer padding and mechanical protection from shocks (think walruses). Another type of lipid forms membrane bilayers, which separate cellular contents from the outside environment or separate intracellular compartments (organelles) from the cytoplasm. Some lipids are released from cells to signal other cells to respond to specific stimuli in a process called cell signaling. From a more molecular perspective, lipids can act as cofactors for enzymes, pigments, antioxidants, and water repellents. As we saw with proteins, lipid structure mediates their function. So, let's probe their structures.

Lipids can be split into structural classes in a variety of ways. An earlier classification divided them into those that release fatty acids under base-catalyzed hydrolysis to form soaps in a saponification reaction and those that don't. A much better and broader classification is based on whether the lipids contain fatty acids or isoprenoids, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) below.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Fatty acids and isoprenoid lipids

The nonpolar chains of the fatty acid are drawn in the figure above in the lowest energy zig-zag fashion, as we saw when we discussed the main chain conformation of proteins (Chapter 4.1). In that chapter, we started by exploring a long 12-C chain of carboxylic acid, dodecanoic acid. In the lowest energy conformation, the dihedral angles are all + 1800 to minimize torsional strain in the molecule. Rotation around one C-C bond can produce a gauche form, which introduces a kink into the chain, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Fatty Acids

Fatty acids can be free or covalently linked by ester or amide link to a base molecule like triglycerides or membrane lipids. The key principle we learned in our study of proteins, which is that structure determines function, also applies to lipids. The figure below shows three types of molecules: a free fatty acid, a wax with an esterified fatty acid, and a glycolipid with a fatty acid connected by an amide link in another type of lipid (glycosphingolipid). Each has different properties, leading to different functions. Waxes, for instance, are very nonpolar and water-insoluble. They are amorphous solids at room temperature but, depending on their structure, can melt to form high-viscosity liquids. They are used as a coating on the surfaces of leaves to help prevent water loss. The glycolipids (glyco- as they contain a monosaccharide group) are constituents of membrane bilayers. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the general structures of fatty acid-containing waxes and other lipids.

Fatty acids vary in length, usually contain an even number of carbon atoms, and can be saturated (have no double bonds in the acyl chain) or unsaturated (with either one -monounsaturated - or multiple - polyunsaturated - cis double bond(s)). The double bonds are NOT conjugated as they are separated by a methylene (-CH2-) spacer. Fatty acids can be named in many ways.

- Symbolic name: given as x:y Δ a,b,c, where x is the number of carbon atoms in the chain, y is the number of double bonds, and a, b, and c are the positions of the start of the double bonds, counting from C1 - the carboxyl carbon. Double bonds are usually cis (Z).

- Systematic name using IUPAC nomenclature. The systematic name gives the number of carbon atoms in the chain (e.g., hexadecanoic acid for 16:0). If the fatty acid is unsaturated, the base name reflects the number of double bonds (e.g., octadecenoic acid for 18:1 Δ 9 and octadecatrienoic acid for 18:3Δ 9,12,15).

- Common name: (e.g., oleic acid, 18:1Δ9), which is found in high concentration in olive oil.

They can be named most efficiently with a symbolic name. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows examples of fatty acids and their symbolic names.

There is an alternative to the symbolic representation of fatty acids, in which the carbon atoms are numbered from the distal end (the n or ω end) of the acyl chain (the opposite end from the alpha carbon). Hence, 18:3 Δ 9,12,15 could be written as 18:3 (ω -3) or 18:3 (n -3), where the terminal C is numbered one and the first double bond starts at C3.

The most common saturated fatty acids in biochemistry textbooks are listed in the table below. Note how the melting point increases with the length of the hydrocarbon chain. This arises from increasing noncovalent induced dipole-induced dipole attractions between the long chains. Heat must be added to lessen these attractions to allow melting. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) below shows examples of fatty acids and their symbolic names.

| Symbolic | common name | systematic name | structure | mp(C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12:0 | Lauric acid | dodecanoic acid | CH3(CH2)10COOH | 44.2 |

| 14:0 | Myristic acid | tetradecanoic acid | CH3(CH2)12COOH | 52 |

| 16:0 | Palmitic acid | Hexadecanoic acid | CH3(CH2)14COOH | 63.1 |

| 18:0 | Stearic acid | Octadecanoic acid | CH3(CH2)16COOH | 69.6 |

| 20:0 | Arachidic acid | Eicosanoic acid | CH3(CH2)18COOH | 75.4 |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Examples of fatty acids and their symbolic names

Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) below shows common unsaturated fatty acids. Arachidonic acid is an (ω -6) fatty acid, while docosahexaenoic acid is an (ω -3) fatty acid. Note the decreasing melting point for the 18:X series with increasing double bonds.

| Symbol | common name | systematic name | structure | mp(C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16:1Δ9 | Palmitoleic acid | Hexadecenoic acid | CH3(CH2)5CH=CH-(CH2)7COOH | -0.5 |

| 18:1Δ9 | Oleic acid | 9-Octadecenoic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH-(CH2)7COOH | 13.4 |

| 18:2Δ9,12 | Linoleic acid | 9,12 -Octadecadienoic acid | CH3(CH2)4(CH=CHCH2)2(CH2)6COOH | -9 |

| 18:3Δ9,12,15 | α-Linolenic acid | 9,12,15 -Octadecatrienoic acid | CH3CH2(CH=CHCH2)3(CH2)6COOH | -17 |

| 20:4Δ5,8,11,14 | arachidonic acid | 5,8,11,14- Eicosatetraenoic acid | CH3(CH2)4(CH=CHCH2)4(CH2)2COOH | -49 |

| 20:5Δ5,8,11,14,17 | EPA | 5,8,11,14,17-Eicosapentaenoic- acid | CH3CH2(CH=CHCH2)5(CH2)2COOH | -54 |

| 22:6Δ4,7,10,13,16,19 | DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid | 22:6w3 |

Table \(\PageIndex{2}\): Common unsaturated fatty acids

Let's consider how double bonds in fatty acids influence their melting points. Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows common variants of fatty acids, each with 18 carbon atoms. Compare the Lewis structure and spacefill models below. What a difference a cis double bond makes!

The double bonds in fatty acids are cis (Z), which introduces a "permanent" kink into the chain, similar to the"temporary" kink in the saturated dodecanoic acid carboxylic acid with a single gauche bond (Figure 2). The kink is permanent since there is no rotation around the double bond unless it is broken (which can happen through photoisomerization reactions). The more double bonds, the greater the kinking. The more kinks, the less chance for van der Waals contacts between the acyl chains, and the reduced induced-dipole-induced dipole interactions between the chains lead to lowered melting points.

In your mind, replace the cis double bond in oleic acid with a trans double bond. You should now see a long "zig-zag" shaped molecule with no kinks. Trans fatty acids are rare in biology but are produced in the industrial partial hydrogenation of fats, which decreases the number of double bonds and makes the fats more solid-like and tastier while decreasing rancidity. These trans fatty acids would pack closer together and affect the structure and function of the lipid in a given environment (such as a membrane bilayer). Increased consumption of trans fatty acids is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Table \(\PageIndex{3}\): shows the percentages of fatty acids in different oils/fats

| FAT | <16:0 | 16:1 | 18:0 | 18:1 | 18:2 | 18:3 | 20:0 | 22:1 | 22:2 | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut | 87 | . | 3 | 7 | 2 | . | . | . | . | . |

| Canola | 3 | . | 11 | 13 | 10 | . | 7 | 50 | 2 | |

| Olive Oil | 11 | . | 4 | 71 | 11 | 1 | . | . | . | . |

| Butter-fat | 50 | 4 | 12 | 26 | 4 | 1 | 2 | . | . | . |

Table \(\PageIndex{3}\): Percentages of fatty acids in different oils/fats

The fatty acid composition differs in different organisms:

- animals have 5-7% of fatty acids with 20-22 carbons, while fish have 25-30%

- animals have <1% of their fatty acids with 5-6 double bonds, while plants have 5-6% and fish 15-30%

As there are essential amino acids that humans cannot synthesize, there are also essential fatty acids that the diet must supply. There are only two, one each, in the n-6 and n-3 classes:

- n-6 class: α-linoleic acid (18:2 n-6, or 18:2Δ9,12) is a biosynthetic precursor of arachidonic acid (20:4 n-6 or 20:4Δ5,8,11,14)

- n-3 class: linolenic acid (18:3 n-3, or 18:3Δ9,12,15) is a biosynthetic precursor of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 n-3 or 20:5Δ5,8,11,14,17) and to a much smaller extent, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 n-3 or 22:6Δ4,7,10,13,16,19).

These two fatty acids are essential since mammals cannot introduce double bonds in fatty acids beyond carbon 9. These essential precursor fatty acids are substrates for intracellular enzymes such as elongases and desaturases (to produce 20:4 n-6, 20:5 n-3, and 22:6 n-3 fatty acids), and beta-oxidation type enzymes in the endoplasmic reticulum and another organelle, the peroxisome. The peroxisome is involved in the oxidative metabolism of straight-chain and branched fatty acids, peroxide metabolism, and cholesterol/bile salt synthesis. Animals fed diets high in plant 18:2(n-6) fats accumulate 20:4(n-6) fatty acids in their tissues, while those fed diets high in plant 18:3(n-3) accumulate 22:6(n-3). Animals fed diets high in fish oils accumulate 20:5 (EPA) and 22:6 (DHA) at the expense of 20:4(n-6).

Many studies support the claim that diets high in fish containing abundant ω-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, reduce inflammation and cardiovascular disease. ω-3 fatty acids are abundant in high-oil fish (salmon, tuna, sardines) and lower in cod, flounder, snapper, shark, and tilapia.

Some suggest that, contrary to images of early hominids as hunters and scavengers of meat, human brain development might have required the consumption of fish, which is highly enriched in arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids. The brain contains lipids that are highly enriched in these two fatty acids. These fatty acids are necessary for the proper development of the human brain. Deficiencies in these might contribute to ADHD, dementia, and dyslexia. These fatty acids are essential in the diet. The mechanism for the protective effects of n-3 fatty acids in health will be explored later in the course when we discuss prostaglandin synthesis and signal transduction.

Aggregates of Fatty Acids in Aqueous Solution: Micelles

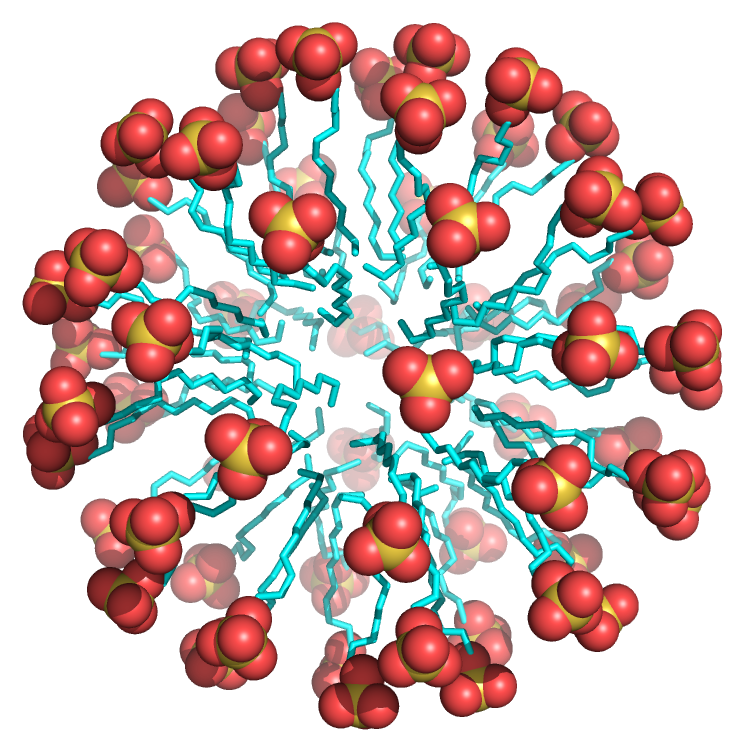

Structure determines both properties and function. It should be evident that free, unesterified fatty acids are very (but not completely) insoluble in water. When added to water, they saturate the solution at very low concentrations and then undergo a phase separation to produce aggregates called micelles. The micelle structure formed from dodecyl sulfate, a common detergent with a sulfate instead of a carboxylate head group, is shown below. All the nonpolar Cs and Hs of the long alkyl chains are "buried" and are not exposed to water, whereas the sulfate head groups are solvent-exposed.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of image

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Sodium dodecylsulfate micelle (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...KECTiGaPPScED7

Fatty acids (carboxylates and sulfates) are amphiphilic, with a larger polar/charged head group that tapers down to a hydrophobic tail, forming a cone-like structure. This cone structure allows the packing of many of these single-chain amphiphiles into a micelle, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

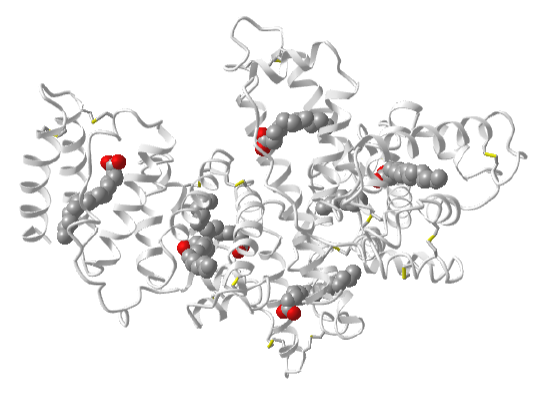

Free fatty acids are transported in the cell and the blood, not in micelles, but by fatty acid-binding proteins. The most abundant protein in the blood, albumin, binds and transports fatty acids. Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of hexadecanoic acid bound to human albumin (1E7H). The fatty acids are shown in colored spacefill rendering.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Hexadecanoic acid bound to human albumin (1E7H). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...CGUdMj11vNevF6

Waxes

You are familiar with earwax and also the waxy surface of plants. Ear wax contains long-chain fatty acids (saturated and unsaturated) and alcohols derived from them. (They also contain isoprenoid derivatives like squalene and cholesterol, discussed below). The waxy cuticle surface layers of plants contain very long-chain fatty acids ( C20–C34) and their derivatives, including alkanes, aldehydes, primary and secondary alcohols, ketones, and esters. We will consider waxes as very long-chain fatty acids and their derivatives, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\).

These molecules are extremely nonpolar and, as such, make great barriers preventing water loss through leaves and water penetration into the ear. This group of molecules clearly shows that the properties (insolubility, high melting point) and function (hydrophobic barrier/protection) arise from structure (very long chain carbon molecules, few electronegative atoms, and lack of C=C double bonds).

Fatty Acid-Containing Lipids

We can categorize these lipids based on function or structure (even though these are related).

Function

- storage lipids - triacylglycerols

- membrane lipids - many different lipids

Structure

- glycerolipids, which use glycerol as a backbone for fatty acid attachment

- sphingolipids, which use sphingosine as a backbone

The structures of glycerol and sphingosine are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\). Fatty acids are connected to these two "backbone" structures by either ester (mostly) or amide links.

Let's explore the classes of fatty acid-containing lipids that use these two "backbone" structures.

Storage Lipids - Triacylglycerols (TAGs)

Most fatty acids in species that store fatty acids for energy are found in triacylglycerols. You will often see them named triglycerides or triacylglycerides, but this term is used more in clinical chemistry and industry (and often in the media). Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) shows a schematic diagram of the glycerol backbone with three fatty acids esterified. They are glycerolipids as they contain a glycerol base.

Glycerol is not chiral, but given the incredible diversity of fatty acids, glycerols likely have three different fatty acids esterified to them, making them chiral. If triacylglycerols contain predominantly saturated fatty acids, they are solids at room temperature and are called fats. Those with multiple double bonds in the fatty acids are likely liquids at room temperature. These are called oils. Triacylglycerols are even more insoluble than fatty acids, which contain a polar and mostly charged carboxylate.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) shows a triacylglycerol containing all 16:0 saturated fatty acids (left) and one containing all 16:2Δ9,12 polyunsaturated fatty acids. The figures were constructed with a specific set of dihedral angles to illustrate a point that polyunsaturated fats in a triacylglycerol don't pack as tightly and have lower induced dipole-induced dipole attractions between the acyl chains than is possible with saturated fatty acyl chains. Hence, the melting point of triacylglycerols containing polyunsaturated fatty acids is lower than that of those with saturated ones.

Let's repeat the key mantra: the structure of lipids determines their function. Consider the very insoluble triacylglycerol used as the body's predominant storage form of chemical energy. In contrast to polysaccharides such as glycogen (a glucose polymer), the carbon atoms in the acyl chains of the triacylglycerol are in a highly reduced state. The main energy source that drives our bodies and society is oxidizing carbon-based molecules to carbon dioxide and water in a highly exergonic and exothermic reaction. Sugars are already partway down the free energy "hill" since each carbon is partially oxidized. 9 kcal/mol (38 kJ/mol) can be derived from the complete oxidation of fats, in contrast to 4.5 kcal/mol (19 kJ/mol) from proteins or carbohydrates.

In addition, glycogen is highly hydrated. For every 1 g of glycogen, 2 g of water is H-bonded. Hence, storing the equivalent mass of carbohydrates would take 3 times more weight than triacylglycerol, which is stored in anhydrous lipid "droplets" within cells. In addition, fats are more flexible, given the large number of conformations available to the acyl chain C-C bonds by simple rotation around the C-C bonds. Polysaccharides have monomeric cyclohexane-like chair structures and are much more rigid.

Triacylglycerols are predominantly stored in special cells called adipocytes, which comprise adipose or fat tissue and must be mobilized by signaling agents and transported as fatty acids to cells for utilization. Again, triacylglycerols don't form membranes, which separate the outside and inside aqueous environments. They are simply so insoluble that they phase-separate into lipid droplets. Their formation and structure are a bit more complex than that, though, and we will discuss lipid droplets more in the next section.

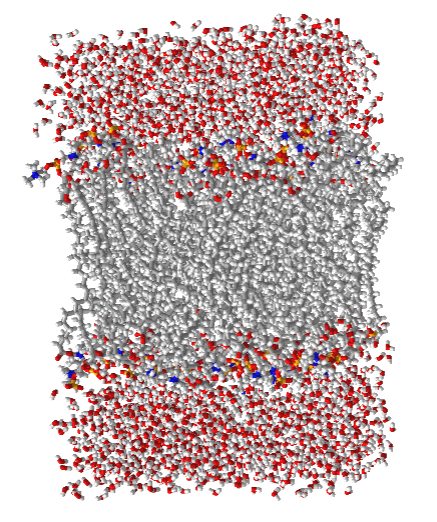

Membrane Lipids

Membranes are bilayers of amphiphilic lipids that separate the outside and inside (cytoplasm) aqueous environments in cells and the cytoplasm and interior contents of organelles within cells. In general, single-chain lipid amphiphiles form micelles. Amphiphilic membrane lipids typically have two nonpolar tails connected to a polar head, giving them a less conical and more cylindrical shape that disallows micelle formation while favoring bilayer formation. Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows a short section of a bilayer membrane made from lipids with a polar (and charged) head group (phosphocholine) and two 16:0 chains. The red and blue spheres represent the O and N atoms of the head groups, which are sequestered to the exterior parts of the bilayer, where they interact with water. The nonpolar 16:0 tails are shown in cyan, clearly illustrating the nonpolar nature of the interior of the bilayer.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a hydrated bilayer of the di16:0 phosphatidylcholine bilayer.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Hydrated di16:0 phosphatidycholine bilayer (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup.

We will consider two general types of fatty acid-containing membrane lipids: glycerolipids, with two fatty acids esterified to a glycerol base, and sphingolipids, with one fatty acid in amide linked to a different base, sphingosine. Sphingosine has a built-in long alkyl chain that provides the "second" nonpolar chain. There are many different polar/charged head groups for these membrane lipids.

Let's look more at the double-chain amphiphiles comprising these membrane bilayers.

Glycerolipids

There are two main glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids and glyceroglycolipids, the most common lipids in membranes.

Glycerophospholipids

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) shows glycerophospholipids' structural features and nomenclature.

These lipids have enormous structural variability, given the large number of different fatty acids (both saturated and unsaturated) and head groups that can be attached to a phosphate attached to carbon 3 of glycerol. Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) shows the structures of the most common glycerophospholipids.

Phosphatidylcholine (PC) is commonly called lecithin, while phosphatidylserine (PS) is called cephalin.

Note that the head groups have charges since they all have a negatively charged phosphate. PS has two additional charged atoms, which would effectively cancel out. PE has a charged amine but could become uncharged at pH values approaching its pKa. PC has a quaternary amine, which is positively charged at all pHs. Hence, PC has a positive and negative charge but a zero net charge.

Glyceroglycolipids

These do not have a phosphate group attached to the oxygen on C3 of glycerol. Rather, they have a mono- or oligosaccharide or, more loosely, a betaine group, each attached by an ether linkage to the glycerol C3 carbon. Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) Structural features and nomenclature for glyceroglycolipids.

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) shows some examples of glyceroglycolipids.

Again, there are an enormous number of different glycoglycerolipids, owing to the diversity of head groups and fatty acids esterified to glycerol at C1 and C2.

The betaine lipids (top right in the figure above) have neither a phosphate nor a sugar in the head group. The head group is betaine (trimethylglycine or any N-trimethylated amino acid). Betaine glycerolipids are found in lower eukaryotic organisms (algae, fungi, and some protozoa), photosynthetic bacteria, and spore-producing plants like ferns. Some would call these lipoamino acids.

A new malarial vaccine with a glycoglycerolipid adjuvant

It is extremely difficult to develop a vaccine against malaria. The resident time of the Plasmodium parasite in the blood after a mosquito bite is quite short (just a few hours), so any immune response against it must be very fast. The sporozoite parasite soon migrates to the liver, proliferating before leaving the liver and infecting red blood cells. The parasite is more sequestered in the liver from the antibody response engendered by typical vaccination, which promotes B-cell differentiation and proliferation into antibody-producing cells. Another type of lymphocyte, T cells, can also be activated in an immune response. In particular, CD8 memory T cells (Trm cells) are produced in the liver against parasites, but high levels are needed. Mouse liver cells make modest levels of Trm cells when vaccinated with mRNAs encoding the Plasmodium's large ribosomal subunit protein L6 (RPL6). This is found in the liver for about a week after infection. However, when an "adjuvant" (something that increases the immune response, usually in a nonspecific way) containing α-galactosylceramide (αGC) is used, there is an increase in the production of liver Trm cells. Chemically modifying the αGC adjuvant greatly increases the production of Trm cells. The structure of αGC and its derivatives is shown below.

The adjuvant interacts as an agonist with type I natural killer T cells, activating them and amplifying the liver's immune response. Mice vaccinated with an mRNA vaccine containing the modified αGC adjuvant were afforded protection against the Plasmodium parasite. The protection extended to mice previously exposed to the parasite as well.

Membrane Lipids - Sphingolipids

Sphingolipids contain a sphingosine backbone and a fatty acid linked through an amide bond. The simplest sphingolipids are the ceramides, which are double-chain amphiphiles but without further modification of the functional groups on the polar head of sphingosine. The structures of both sphingosine and ceramide are shown below in Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\):

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\): Structures of sphingosine and ceramide

Ceramides are abundant in the skin and help provide a protective barrier. Skin creams also contain ceramides. These lipids comprise only about 1% of body lipids, and over 200 different ceramides in humans arise from the different fatty acids linked to sphingosine. They have a key role in cell signaling and can also affect cardiovascular health in ways that are just being appreciated. Since they are double-chain amphiphiles, they are found in membranes where they alter the properties of the bilayer (including membrane fluidity). Ceramides with long acyl tails (especially those with 16, 18, or 24 carbons) are especially abundant in the skin.

Phosphosphingolipids and glycosphingolipids

These membrane lipids have a ceramide base but also contain modifications at the polar functional groups of the sphingosine head. Let's consider the phosphosphingolipids and the glycosphingolipids together. These groups do not use glycerol as a base for the attachment of fatty acids and head groups. Rather, they use the molecule sphingosine. Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) shows sphingolipids' structural features and nomenclature.

Examples of both classes are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\). Note that the base sphingosine (in red) provides an amine to attach a fatty acid through an amide bond and an OH for attachment to the head group.

Sugar-containing glycosphingolipids are found largely in the outer face of plasma membranes. The primary lipid of myelin, which coats neuronal axons and insulates them from loss of electrical signaling down the axon, is galactocerebroside

Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\) shows a summary of all of the different types of fatty acid-containing lipids

The complexity of biological lipids can be overwhelming. They are derived from two building blocks, ketoacyl and isoprene groups, which are modified with other groups. The Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy (LIPID MAPS) consortium has offered a very detailed and encompassing definition of lipids: "hydrophobic or amphipathic small molecules that may originate entirely or in part by carbanion-based condensations of thioesters (fatty acids, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides) and/or by carbocation-based condensations of isoprene units (prenol lipids and sterol lipids)." Eight different categories of lipids are listed in the parentheses above.

Shapes of membrane lipids

Let's look at the general shape of the double-chain amphiphiles that make bilayers. We saw the long-chain fatty or sulfate acids form conical structures that fit nicely together when they self-aggregate to form micelles. In contrast, membrane-forming double-chain amphiphiles have more cylindrical shapes that can't be fitted together in micelles but form a less curved bilayer structure, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\). We will consider the variety of membrane structures in the next section.

Triacylglycerol/Phospholipid Stereochemistry

Glycerol is an achiral molecule since C2 has two identical substituents, -CH2OH. Biologically, glycerol can be chemically converted to chiral phospholipids (PL) of just one enantiomer. How can this be possible if the two CH2OH groups on C2 of glycerol are identical? It turns out that even though these groups are stereochemically equivalent, we can differentiate them as described in the figure below. Let's replace the -CH2OH in one of the end carbons with -CH2OD. With this simple change, glycerol is now chiral. Look at the top half of Figure \(\PageIndex{24}\).

Glycerol is oriented with the OH on C2 (the middle carbon) pointing to the left. The OH of the top carbon in this orientation, C1, is replaced with OD, where D is deuterium, to make the molecule chiral (four different groups attached to C2). By rotating the molecule such that the H on C2 points to the back and assigning priorities to the other substituents on C2 (OH =1, DOCH2 =2, and CH2OH = 3), it can be seen that the resulting molecule is in the S configuration. We simply name the C1 carbon, which we modified with deuterium, the proS carbon. Likewise, if we replaced the OH on C3 with OD, we would form the R enantiomer. Hence, C3 is the proR carbon. This shows that we can actually differentiate between the two identical CH2OH substituents. We say that glycerol is not chiral, but prochiral. (Think of this as glycerol has the potential to become chiral by modifying one of two identical substituents.)

In the bottom half of Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\), we can relate the configuration of glycerol above (when OH on C2 is pointing to the left) to the absolute configuration of L-glyceraldehyde, a simple sugar (a polyhydroxyaldehyde or ketone), another 3C glycerol derivative. This molecule is chiral, with the OH on C2 (the only chiral carbon) pointing to the left. It is easy to remember that any L sugar has the OH on the Last chiral carbon pointing to the Left. The enantiomer (mirror image isomer) of L-glyceraldehyde is D-glyceraldehyde, in which the OH on C2 points to the right. Biochemists use L and D for lipid, sugar, and amino acid stereochemistry instead of the R and S nomenclature used in organic chemistry. The stereochemical designation of all the sugars, amino acids, and glycerolipids can be determined from the absolute configuration of L- and D-glyceraldehyde.

Now let's see how an enzyme can take a prochiral molecule like glycerol and phosphorylate only one of the -CH2OHs to make one specific isomer, glycerol-3-phosphate, a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of phosphatidic acid (PA), a glycerophospholipid, as well as chiral triacylglycerols, shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{25}\). The far left part of the pathway shows how the proR CH2OH of glycerol is phosphorylated to produce one specific enantiomer, L-glycerol-3-phosphate. (The top part of the figure shows another way to make this molecule from glucose through the glycolytic pathway, which we will encounter in a future chapter.

The first step (above figure) involves the phosphorylation of the OH on C3 by ATP (a phosphoanhydride similar in structure to acetic anhydride, an excellent acetylating agent) to produce the chiral glycerol phosphate. Based on the absolute configuration of L-glyceraldehyde and using this to draw glycerol (with the OH on C2 pointing to the left), we can see that the phosphorylated molecule can be named L-glycerol-3-phosphate. By rotating this molecule 180 degrees, without changing the stereochemistry of the molecule, we don't change the molecule at all, but using the D/L nomenclature above, we would name the rotated molecule D-glycerol-1-phosphate. This is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{26}\).

We can’t give the same molecule two different names. Hence, biochemists have developed the stereospecific numbering system (sn), which assigns the 1-position of a prochiral molecule to the group occupying the proS position. The proS C1 is, hence, at the sn-1 position. With that designation, C2 is at the sn-2 position, and C3 is at the sn-3 position. Using this nomenclature, we can see that the chiral molecule described above, glycerol-phosphate, can be unambiguously named sn-glycerol-3-phosphate. The hydroxyl substituent on the proR carbon was phosphorylated.

Interestingly, archaea use isoprenoid chains linked by ether bonds to sn-glycerol 1-phosphate in their synthetic pathways. As noted above, bacteria and eukaryotes use fatty acids attached by ester bonds to sn-glycerol 3-phosphate

The enzymatic phosphorylation of the proR CH2OH of glycerol to form sn-glycerol-3-phosphate is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{27}\). As we could differentiate the two identical CH2OH substituents as containing either the proS or proR carbons, so can the enzyme. The enzyme can differentiate identical substituents on a prochiral molecule if the prochiral molecule interacts with the enzyme at three points. Another example of a prochiral reactant/enzyme system involves the oxidation of the prochiral molecule ethanol by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, in which only the proR H of the 2 H’s on C2 is removed. (We will discuss this later.)

Isoprenoid-containing lipids

This is the last class of lipids we will consider. They do not contain fatty acids. Rather, they contain isoprene, a small branched alkadiene, which can polymerize into larger molecules containing isoprene monomer to form isoprenoids, often called terpenes. Instead of using isoprene as the polymerization monomer, either dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) or isopentenylpyrophosphate (IPP) is used biologically.

Figure \(\PageIndex{28}\) shows how DMAPP and IPP (both containing 5Cs) are used in a polymerization reaction to form geranyl-pyrophosphate (C10), farnesyl pyrophosphate (C15), and geranyl-geranyl pyrophosphate (C20).

Many isoprenoid lipids are made from farnesyl pyrophosphate. For membrane purposes, the most important of these is cholesterol. Figure \(\PageIndex{29}\) shows an overview of the synthesis of cholesterol from two farnesyl pyrophosphates linking together in a "tail-to-tail" reaction to form squalene, a precursor of cholesterol. Each isoprene unit (5Cs) is shown in different colors for easier visualization.

Figure \(\PageIndex{30}\) shows other biologically important isoprenoid-containing vitamins.

The smell of fresh rain

Everyone who has walked in the woods after a fresh rain knows the smell of a terpene called geosmin, "an Earthy-smelling substance" found in abundance in a group of substances collectively called petrichor, derived from the Greek petra (rock) and ichor (blood of gods). The structure of geosmin is shown below.

These substances are released when water falls on soils and rocks and seep into pores from which aerosols are released. Too much rain will saturate the pores in rocks and prevent the release of geosmin. Some insects, like the springtail, are attracted to geosmin. The synthesis of geosmin by bacteria and blue-green algae is controlled by transcription factors, which also affect bacterial spore formation. The attracted insects carry away the spores. Flies are repelled by geosmin, which is detected by a receptor at very low geosmin concentrations. In contrast, the Aedes aegypti mosquito is attracted to geosmin, which parallels the fact that the mosquito is unaffected by bacterial toxins.

One last look at lipid structure and shapes

With the exclusion of waxes and triacylglycerols, the other lipids we have discussed, including the mostly planar molecule cholesterol, are amphiphilic. Single-chain fatty acids form micelles, while lipids with two nonpolar chains and a polar/charged head group form bilayers. Given the relative size of the head group and the degree of unsaturation of the double bonds in fatty acids, the overall shapes of the membrane-forming lipids differ, as illustrated below. They are arranged like dominoes in the membrane based on their geometric volumes. Preferential clustering of identical types can cause local and extended changes in a prototypical bilayer structure.

Membranes and their components must be dynamic to enable all the functions and activities of a membrane. Ligands bind to membrane receptors (usually proteins), which can invaginate and pinch off to form an intracellular vesicle containing the receptor for processing. Likewise, vesicles can pinch off into the extracellular space. Cells must divide. Think of the membrane changes necessary for that! Also, consider that the length of cholesterol is half that of a typical double-chain amphiphile. Hence, it fits into just one of the bilayer lipid leaflets, where it modulates lipid bilayer properties. Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\) shows a series of lipids and their shape profiles.

We will consider membranes in greater detail in Section 10.3. Next, we will explore the properties of micelle and lipid droplet systems in more detail before addressing the more structurally complicated lipid bilayers.

Summary

This chapter explores the structural diversity and multifaceted functions of lipids in biological systems, emphasizing the fundamental principle that structure determines function. Lipids are defined as organic molecules that are soluble in organic solvents but largely insoluble in water due to their hydrophobic nature. This property underlies their roles in energy storage, insulation, mechanical protection, membrane formation, and cellular signaling.

The chapter begins by classifying lipids based on their chemical building blocks into those derived from fatty acids and those composed of isoprenoids. Fatty acids, which can be saturated or unsaturated, exhibit structural variations such as chain length and the presence of cis or trans double bonds. These variations significantly influence their physical properties—for example, melting points—by affecting the packing of acyl chains. Essential fatty acids from the n-6 and n-3 families are discussed, highlighting their importance in health, including their roles in brain development and cardiovascular protection.

In addition to free fatty acids, the chapter reviews complex lipids. Storage lipids, particularly triacylglycerols, serve as anhydrous energy reserves, contrasting with hydrated carbohydrates like glycogen. Membrane lipids are predominantly amphiphilic, with two distinct classes highlighted: glycerolipids (including glycerophospholipids and glyceroglycolipids) and sphingolipids. These lipids self-assemble into bilayers, forming the structural basis of cellular membranes. The stereochemistry of glycerol, although initially achiral, becomes crucial upon esterification, leading to specific configurations (using the stereospecific numbering system) that affect membrane function.

The chapter also examines isoprenoid lipids, which are synthesized from five-carbon isoprene units. These lipids, including cholesterol and various terpenes, play key roles in membrane structure, serve as precursors for vitamin synthesis, and contribute to sensory properties like the characteristic earthy smell of geosmin.

Finally, the text discusses the self-assembly behavior of lipids in aqueous environments. It explains how amphiphilic lipids form micelles and bilayers based on the geometric differences between single-chain (conical) and double-chain (cylindrical) structures, which are critical for processes such as membrane fluidity and vesicle formation.

Overall, the chapter illustrates how the unique chemical structures of lipids enable them to fulfill diverse biological roles—from energy storage to forming the dynamic boundaries of cells—and sets the stage for deeper exploration of membrane biochemistry and lipid signaling pathways in later sections.