19.2: Waste Disposal

- Page ID

- 35011

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)There are three primary methods for waste disposal: open dumps, sanitary landfills, and incineration. Sanitary landfills and incineration prevent reuse, recycling, and proper decomposition. While open dumps promote decomposition better than other methods of waste disposal and allow discarded materials to be salvaged or recycled, they promote disease spread and cause water pollution. They are thus illegal in many countries.

Open Dumps

Open dumps involve simply piling up trash in a designated area and is thus the easiest method of waste disposal (figure \(\PageIndex{a}\)). Open dumps can support populations of organisms that house and transmit disease (reservoirs and vectors, respectively). Additionally, contaminants from the trash mix with rain water forming leachate, which infiltrates into the ground or runs off. This liquid leachate may contain toxic chemicals such as dioxin (a persistent organic pollutant), mercury, and pesticides.

Sanitary Landfills

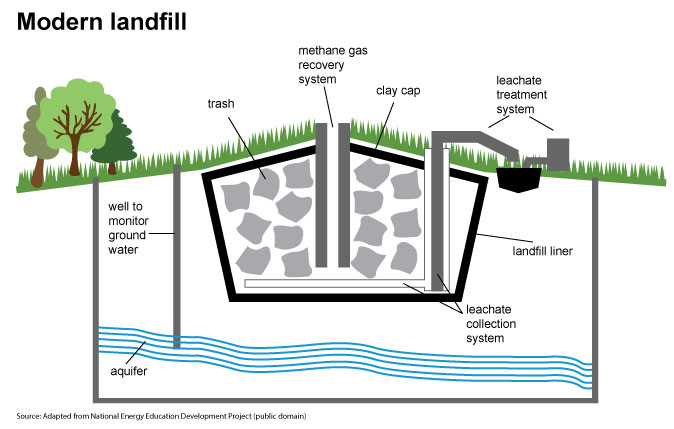

After recycling, composting, and incineration, the remaining 50% of municipal solid waste (MSW) in the U.S. was discarded in sanitary landfills (figure \(\PageIndex{b}\)). Trash is sealed from the top and the bottom to reduce contamination of surroundings (figure \(\PageIndex{c}\)). Rainwater that percolates through a sanitary landfill is collected in the bottom liner, and this bottom layer thus prevents contamination of groundwater. The groundwater near the landfill is closely monitored for signs of contamination from the leachate. Layers of soil on top prevent disease spread. Each day after garbage is dumped in the landfill, it is covered with clay or plastic to prevent redistribution by animals or the wind.

Several practices can reduce the environmental impact of sanitary landfills. Compacting in landfills reduces water and oxygen levels, slowing decomposition and promoting methane release. In the U.S., the Clear Air Act requires that landfills of a certain size collect landfill gas (biogas), which can be used as a biofuel for heating or electricity generation. Other gases such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide may also be released by the landfill, contributing to air pollution. These gases are also monitored and, if necessary, collected for disposal. To address the often dry condition of wastes within landfills, the concept of bioreactor landfills has emerged. These recirculate leachate and/or inject other liquids to increase moisture and promote decomposition (and therefore increasing the rate of biogas production). Upon closure, many landfills undergo "land recycling" and can be redeveloped as golf courses, recreational parks, and other beneficial uses.

With respect to waste mitigation options, landfilling is quickly evolving into a less desirable or feasible option. Landfill capacity in the United States has been declining for several reasons. Older existing landfills are increasingly reaching their authorized capacity. Additionally, stricter environmental regulations have made establishing new landfills increasingly difficult. Finally, public opposition delays or, in many cases, prevents the approval of new landfills or expansion of existing facilities.

Incineration

Incineration is simply burning trash. This has several advantages: it reduces volume and can be used to generate electricity (waste-to-energy). In fact, the sheer volume of the waste is reduced by about 85%. Incineration is costly, however, and it pollutes air and water. Air pollutants released by incineration include particulates, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, methane, heavy metals (such as lead and mercury), and dioxins. The byproduct of incineration, ash, is often toxic. Depending on its composition, ash might require special disposal; other types of ash can be repurposed.

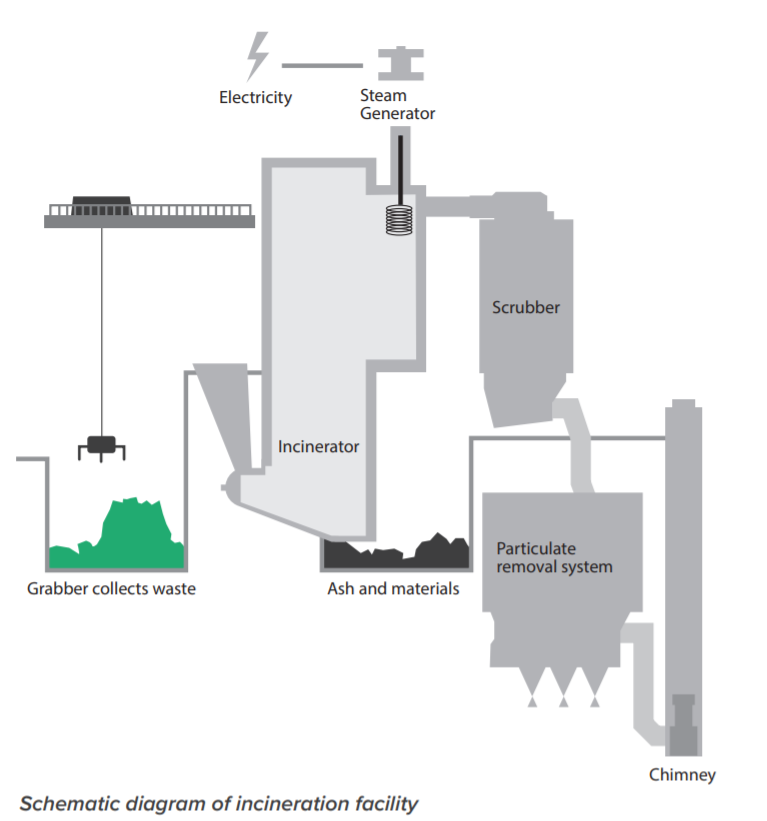

An incinerator processes trash and burns it in a combustion chamber (figure \(\PageIndex{d-e}\)). The heat boils water, and the resultant steam is used to generate electricity. The smoke (called flue gases) goes through a pollution-removal before it is released, but it still contains some pollutants. The U.S. incinerated 11.8% of MSW in 2018.

There are two kinds of waste-to-energy systems: mass burn incinerators and refuse-derived incinerators. In mass burn incinerators all of the solid waste is incinerated. The heat from the incineration process is used to produce steam. This steam is used to drive electric power generators. Acid gases from the burning are removed by chemical scrubbers. Any particulates (small particles that remain suspended in the air) in the combustion gases are removed by electrostatic precipitators, which charge particulates and remove them with electrodes. The cleaned gases are then released into the atmosphere through a tall stack. The ashes from the combustion are sent to a landfill for disposal.

It is best if only combustible items (paper, wood products, and plastics) are burned. In a refuse-derived incinerator, non-combustible materials are separated from the waste. Items such as glass and metals may be recycled. The combustible wastes are then formed into fuel pellets which can be burned in standard steam boilers. This system has the advantage of removing potentially harmful materials from waste before it is burned. It also provides for some recycling of materials.

Attribution

Modified by Melissa Ha from the following sources:

- Systems of Waste Management from Sustainability: A Comprehensive Foundation by Tom Theis and Jonathan Tomkin, Editors (CC-BY). Download for free at CNX.

- Solid Waste from AP Environmental Science by University of California College Prep (CC-BY). Download for free at CNX.

- Biomass explained: Landfill gas and biogas. 2020. EIA. Accessed 01-18-2021 (public domain).