S2018_Lecture15_Reading

- Page ID

- 11499

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction to Respiration and Electron Transport Chains

General Overview and Points to Keep In Mind

In the next few modules, we start to learn about the process of respiration and the roles that electron transport chains play in this process. A definition of the word "respiration" that most people are familiar with is "the act of breathing". When we breath, air including molecular oxygen is brought into our lungs from outside of the body, the oxygen then becomes reduced, and waste products, including the reduced oxygen in the form of water, are exhaled. More generically, some reactant comes into the organism and then gets reduced and leaves the body as a waste product.

This generic idea, in a nutshell, can be generally applied across biology. Note that oxygen need not always be the compound that brought in, reduced, and dumped as waste. The compounds onto which the electrons that are "dumped" are more specifically known as "terminal electron acceptors." The molecules from which the electrons originate vary greatly across biology (we have only looked at one possible source - the reduced carbon-based molecule glucose).

In between the original electron source and the terminal electron acceptor are a series of biochemical reactions involving at least one red/ox reaction. These red/ox reactions harvest energy for the cell by coupling exergonic red/ox reaction to an energy-requiring reaction in the cell. In respiration, a special set of enzymes carry out a linked series of red/ox reactions that ultimately transfer electrons to the terminal electron acceptor.

These "chains" of red/ox enzymes and electron carriers are called electron transport chains (ETC). In aerobically respiring eukaryotic cells the ETC is composed of four large, multi-protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane and two small diffusible electron carriers shuttling electrons between them. The electrons are passed from enzyme to enzyme through a series of red/ox reactions. These reactions couple exergonic red/ox reactions to the endergonic transport of hydrogen ions across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This process contributes to the creation of a transmembrane electrochemical gradient. The electrons passing through the ETC gradually lose potential energy up until the point they are deposited on the terminal electron acceptor which is typically removed as waste from the cell. When oxygen acts as the final electron acceptor, the free energy difference of this multi-step red/ox process is ~ -60 kcal/mol when NADH donates electrons or ~ -45 kcal/mol when FADH2 donates.

Note: Oxygen is not the only, nor most frequently used, terminal electron acceptor in nature

Recall, that we use oxygen as an example of only one of numerous possible terminal electron acceptors that can be found in nature. The free energy differences associated with respiration in anaerobic organisms will be different.

In prior modules we discussed the general concept of red/ox reactions in biology and introduced the Electron Tower, a tool to help you understand red/ox chemistry and to estimate the direction and magnitude of potential energy differences for various red/ox couples. In later modules, substrate level phosphorylation and fermentation were discussed and we saw how exergonic red/ox reactions could be directly coupled by enzymes to the endergonic synthesis of ATP.

These processes are hypothesized to be one of the oldest forms of energy production used by cells. In this section we discuss the next evolutionary advancement in cellular energy metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation. First and foremost recall that, oxidative phosphorylation does not imply the use of oxygen. Rather the term oxidative phosphorylation is used because this process of ATP synthesis relies on red/ox reactions to generate a electrochemical transmembrane potential that can then be used by the cell to do the work of ATP synthesis.

A Quick Overview of Principles Relevant to Electron Transport Chains

An ETC begins with the addition of electrons, donated from NADH, FADH2 or other reduced compounds. These electrons move through a series of electron transporters, enzymes that are embedded in a membrane, or other carriers that undergo red/ox reactions. The free energy transferred from these exergonic red/ox reactions is often coupled to the endergonic movement of protons across a membrane. Since the membrane is an effective barrier to charged species, this pumping results in an unequal accumulation of protons on either side of the membrane. This in turn "polarizes" or "charges" the membrane, with a net positive (protons) on one side of the membrane and a negative charge on the other side of the membrane. The separation of charge creates an electrical potential. In addition, the accumulation of protons also causes a pH gradient known as a chemical potential across the membrane. Together these two gradients (electrical and chemical) are called an electro-chemical gradient.

Review: The Electron Tower

Since red/ox chemistry is so central to the topic we begin with a quick review of the table of reduction potential - sometimes called the "red/ox tower" or "electron tower". You may hear your instructors use these terms interchangeably. As we discussed in previous modules, all kinds of compounds can participate in biological red/ox reactions. Making sense of all of this information and ranking potential red/ox pairs can be confusing. A tool has been developed to rate red/ox half reactions based on their reduction potentials or E0' values. Whether a particular compound can act as an electron donor (reductant) or electron acceptor (oxidant) depends on what other compound it is interacting with. The red/ox tower ranks a variety of common compounds (their half reactions) from most negative E0', compounds that readily get rid of electrons, to the most positive E0', compounds most likely to accept electrons. The tower organizes these half reactions based on the ability of electrons to accept electrons. In addition, in many red/ox towers each half reaction is written by convention with the oxidized form on the left followed by the reduced form to its right. The two forms may be either separated by a slash, for example the half reaction for the reduction of NAD+ to NADH is written: NAD+/NADH + 2e-, or by separate columns. An electron tower is shown below.

Note

Use the red/ox tower above as a reference guide to orient you as to the reduction potential of the various compounds in the ETC. Red/ox reactions may be either exergonic or endergonic depending on the relative red/ox potentials of the donor and acceptor. Also remember there are many different ways of looking at this conceptually; this type of red/ox tower is just one way.

Note: Language shortcuts reappear

In the red/ox table above some entries seem to be written in unconventional ways. For instance Cytochrome cox/red. There only appears to be one form listed. Why? This is another example of language shortcuts (likely because someone was too lazy to write cytochrome twice) that can be confusing - particularly to students. The notation above could be rewritten as Cytochrome cox/Cytochrome cred to indicate that the cytochrome c protein can exist in either and oxidized state Cytochrome cox or reduced state Cytochrome cred.

Review Red/ox Tower Video

For a short video on how to use the red/ox tower in red/ox problems click here. This video was made by Dr. Easlon for Bis2A students.

Using the red/ox tower: A tool to help understand electron transport chains

By convention the tower half reactions are written with the oxidized form of the compound on the left and the reduced form on the right. Notice that compounds such as glucose and hydrogen gas are excellent electron donors and have very low reduction potentials E0'. Compounds, such as oxygen and nitrite, whose half reactions have relatively high positive reduction potentials (E0') generally make good electron acceptors are found at the opposite end of the table.

Example: Menaquinone

Let's look at menaquinoneox/red. This compound sits in the middle of the red/ox tower with an half-reaction E0' value of -0.074 eV. Menaquinoneox can spontaneously (ΔG<0) accept electrons from reduced forms of compounds with lower half-reaction E0'. Such transfers form menaquinonered and the oxidized form of the original electron donor. In the table above, examples of compounds that could act as electron donors to menaquinone include FADH2, an E0' value of -0.22, or NADH, with an E0' value of -0.32 eV. Remember the reduced forms are on the right hand side of the red/ox pair.

Once menaquinone has been reduced, it can now spontaneously (ΔG<0) donate electrons to any compound with a higher half-reaction E0' value. Possible electron acceptors include cytochrome box with an E0' value of 0.035 eV; or ubiquinoneox with an E0' of 0.11 eV. Remember that the oxidized forms lie on the left side of the half reaction.

Electron Transport Chains

An electron transport chain, or ETC, is composed of a group of protein complexes in and around a membrane that help energetically couple a series of exergonic/spontaneous red/ox reactions to the endergonic pumping of protons across the membrane to generate an electrochemical gradient. This electrochemical gradient creates a free energy potential that is termed a proton motive force whose energetically "downhill" exergonic flow can later be coupled to a variety of cellular processes.

ETC overview

Step 1: Electrons enter the ETC from an electron donor, such as NADH or FADH2, which are generated during a variety of catabolic reactions, including those associated glucose oxidation. Depending on the number and types of electron carriers of the ETC being used by an organism, electrons can enter at a variety of places in the electron transport chain. Entry of electrons at a specific "spot" in the ETC depends upon the respective reduction potentials of the electron donors and acceptors.

Step 2: After the first red/ox reaction, the initial electron donor will become oxidized and the electron acceptor will become reduced. The difference in red/ox potential between the electron acceptor and donor is related to ΔG by the relationship ΔG = -nFΔE, where n = the number of electrons transferred and F = Faraday's constant. The larger a positive ΔE, the more exergonic the red/ox reaction is.

Step 3: If sufficient energy is transferred during an exergonic red/ox step, the electron carrier may couple this negative change in free energy to the endergonic process of transporting a proton from one side of the membrane to the other.

Step 4: After usually multiple red/ox transfers, the electron is delivered to a molecule known as the terminal electron acceptor. In the case of humans, the terminal electron acceptor is oxygen. However, there are many, many, many, other possible electron acceptors in nature; see below.

Note: possible discussion

Electrons entering the ETC do not have to come from NADH or FADH2. Many other compounds can serve as electron donors; the only requirements are (1) that there exists an enzyme that can oxidize the electron donor and then reduce another compound, and (2) that the ∆E0' is positive (e.g., ΔG<0). Even a small amounts of free energy transfers can add up. For example, there are bacteria that use H2 as an electron donor. This is not too difficult to believe because the half reaction 2H+ + 2 e-/H2 has a reduction potential (E0') of -0.42 V. If these electrons are eventually delivered to oxygen, then the ΔE0' of the reaction is 1.24 V, which corresponds to a large negative ΔG (-ΔG). Alternatively, there are some bacteria that can oxidize iron, Fe2+ at pH 7 to Fe3+ with a reduction potential (E0') of + 0.2 V. These bacteria use oxygen as their terminal electron acceptor, and, in this case, the ΔE0' of the reaction is approximately 0.62 V. This still produces a -ΔG. The bottom line is that, depending on the electron donor and acceptor that the organism uses, a little or a lot of energy can be transferred and used by the cell per electrons donated to the electron transport chain.

What are the complexes of the ETC?

ETCs are made up of a series (at least one) of membrane-associated red/ox proteins or (some are integral) protein complexes (complex = more than one protein arranged in a quaternary structure) that move electrons from a donor source, such as NADH, to a final terminal electron acceptor, such as oxygen. This particular donor/terminal acceptor pair is the primary one used in human mitochondria. Each electron transfer in the ETC requires a reduced substrate as an electron donor and an oxidized substrate as the electron acceptor. In most cases, the electron acceptor is a member of the enzyme complex itsef. Once the complex is reduced, the complex can serve as an electron donor for the next reaction.

How do ETC complexes transfer electrons?

As previously mentioned, the ETC is composed of a series of protein complexes that undergo a series of linked red/ox reactions. These complexes are in fact multi-protein enzyme complexes referred to as oxidoreductases or simply, reductases. The one exception to this naming convention is the terminal complex in aerobic respiration that uses molecular oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor. That enzyme complex is referred to as an oxidase. Red/ox reactions in these complexes are typically carried out by a non-protein moiety called a prosthetic group. The prosthetic groups are directly involved in the red/ox reactions being catalyzed by their associated oxidoreductases. In general, these prosthetic groups can be divided into two general types: those that carry both electrons and protons and those that only carry electrons.

Note

This use of prosthetic groups by members of ETC is true for all of the electron carriers with the exception of quinones, which are a class of lipids that can directly be reduced or oxidized by the oxidoreductases. Both the Quinone(red) and the Quinone(ox) forms of these lipids are soluble within the membrane and can move from complex to complex to shuttle electrons.

The electron and proton carriers

- Flavoproteins (Fp), these proteins contain an organic prosthetic group called a flavin, which is the actual moiety that undergoes the oxidation/reduction reaction. FADH2 is an example of an Fp.

- Quinones are a family of lipids, which means they are soluble within the membrane.

- It should also be noted that NADH and NADPH are considered electron (2e-) and proton (2 H+) carriers.

Electron carriers

- Cytochromes are proteins that contain a heme prosthetic group. The heme is capable of carrying a single electron.

- Iron-Sulfur proteins contain a nonheme iron-sulfur cluster that can carry an electron. The prosthetic group is often abbreviated as Fe-S

Aerobic versus anaerobic respiration

We humans use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor for the ETCs in our cells. This is also the case for many of the organisms we intentionally and frequently interact with (e.g. our classmates, pets, food animals, etc). We breath in oxygen; our cells take it up and transport it into the mitochondria where it is used as the final acceptor of electrons from our electron transport chains. That process - because oxygen is used as the terminal electron acceptor - is called aerobic respiration.

While we may use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor for our respiratory chains, this is not the only mode of respiration on the planet. Indeed, the more general processes of respiration evolved at a time when oxygen was not a major component of the atmosphere. As a consequence, many organisms can use a variety of compounds including nitrate (NO3-), nitrite (NO2-), even iron (Fe3+) as terminal electron acceptors. When oxygen is NOT the terminal electron acceptor, the process is referred to as anaerobic respiration. Therefore, respiration or oxidative phosphorylation does not require oxygen at all; it simply requires a compound with a high enough reduction potential to act as a terminal electron acceptor, accepting electrons from one of the complexes within the ETC.

The ability of some organisms to vary their terminal electron acceptor provides metabolic flexibility and can ensure better survival if any given terminal acceptor is in limited supply. Think about this: in the absence of oxygen, we die; but other organisms can use a different terminal electron acceptor when conditions change in order to survive.

A generic example: A simple, two-complex ETC

The figure below depicts a generic electron transport chain, composed of two integral membrane complexes; Complex I(ox) and Complex II(ox). A reduced electron donor, designated DH (such as NADH or FADH2) reduces Complex I(ox), giving rise to the oxidized form D (such as NAD+ or FAD+). Simultaneously, a prosthetic group within Complex I is now reduced (accepts the electrons). In this example, the red/ox reaction is exergonic and the free energy difference is coupled by the enzymes in Complex I to the endergonic translocation of a proton from one side of the membrane to the other. The net result is that one surface of the membrane becomes more negatively charged, due to an excess of hydroxyl ions (OH-), and the other side becomes positively charged due to an increase in protons on the other side. Complex I(red) can now reduce a mobile electron carrier Q, which will then move through the membrane and transfer the electron(s) to the prosthetic group of Complex II(red). Electrons pass from Complex I to Q then from Q to Complex II via thermodynamically spontaneous red/ox reactions, regenerating Complex I(ox), which can repeat the previous process. Complex II(red) then reduces A, the terminal electron acceptor to regenerate Complex II(ox) and create the reduced form of the terminal electron acceptor, AH. In this specific example, Complex II can also translocate a proton during the process. If A is molecular oxygen, AH represents water and the process would be considered to be a model of an aerobic ETC. By contrast, if A is nitrate, NO3-, then AH represents NO2- (nitrite) and this would be an example of an anaerobic ETC.

Figure 1. Generic 2 complex electron transport chain. In the figure, DH is the electron donor (donor reduced), and D is the donor oxidized. A is the oxidized terminal electron acceptor, and AH is the final product, the reduced form of the acceptor. As DH is oxidized to D, protons are translocated across the membrane, leaving an excess of hydroxyl ions (negatively charged) on one side of the membrane and protons (positively charged) on the other side of the membrane. The same reaction occurs in Complex II as the terminal electron acceptor is reduced to AH.

Attribution: Marc T. Facciotti (original work)

Exercise 1

Thought question

Based on the figure above, use an electron tower to figure out the difference in the electrical potential if (a) DH is NADH and A is O2, and (b) DH is NADH and A is NO3-. Which pairs of electron donor and terminal electron acceptor (a) or (b) "extract" the greatest amount of free energy?

Detailed look at aerobic respiration

The eukaryotic mitochondria has evolved a very efficient ETC. There are four complexes composed of proteins, labeled I through IV depicted in the figure below. The aggregation of these four complexes, together with associated mobile, accessory electron carriers, is called also called an electron transport chain. This type of electron transport chain is present in multiple copies in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes.

Figure 2. The electron transport chain is a series of electron transporters embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane that shuttles electrons from NADH and FADH2 to molecular oxygen. In the process, protons are pumped from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space, and oxygen is reduced to form water.

Complex I

To start, two electrons are carried to the first protein complex aboard NADH. This complex, labeled I in Figure 2, includes flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and iron-sulfur (Fe-S)-containing proteins. FMN, which is derived from vitamin B2, also called riboflavin, is one of several prosthetic groups or cofactors in the electron transport chain. Prosthetic groups are organic or inorganic, nonpeptide molecules bound to a protein that facilitate its function; prosthetic groups include coenzymes, which are the prosthetic groups of enzymes. The enzyme in Complex I is also called NADH dehydrogenase and is a very large protein containing 45 individual polypeptide chains. Complex I can pump four hydrogen ions across the membrane from the matrix into the intermembrane space thereby helping to generate and maintain a hydrogen ion gradient between the two compartments separated by the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Q and Complex II

Complex II directly receives FADH2, which does not pass through Complex I. The compound connecting the first and second complexes to the third is ubiquinone (Q). The Q molecule is lipid soluble and freely moves through the hydrophobic core of the membrane. Once it is reduced, (QH2), ubiquinone delivers its electrons to the next complex in the electron transport chain. Q receives the electrons derived from NADH from Complex I and the electrons derived from FADH2 from Complex II, succinate dehydrogenase. Since these electrons bypass and thus do not energize the proton pump in the first complex, fewer ATP molecules are made from the FADH2 electrons. As we will see in the following section, the number of ATP molecules ultimately obtained is directly proportional to the number of protons pumped across the inner mitochondrial membrane.

Complex III

The third complex is composed of cytochrome b, another Fe-S protein, Rieske center (2Fe-2S center), and cytochrome c proteins; this complex is also called cytochrome oxidoreductase. Cytochrome proteins have a prosthetic group of heme. The heme molecule is similar to the heme in hemoglobin, but it carries electrons, not oxygen. As a result, the iron ion at its core is reduced and oxidized as it passes the electrons, fluctuating between different oxidation states: Fe2+ (reduced) and Fe3+ (oxidized). The heme molecules in the cytochromes have slightly different characteristics due to the effects of the different proteins binding them, giving slightly different characteristics to each complex. Complex III pumps protons through the membrane and passes its electrons to cytochrome c for transport to the fourth complex of proteins and enzymes (cytochrome c is the acceptor of electrons from Q; however, whereas Q carries pairs of electrons, cytochrome c can accept only one at a time).

Complex IV

The fourth complex is composed of cytochrome proteins c, a, and a3. This complex contains two heme groups (one in each of the two Cytochromes, a, and a3) and three copper ions (a pair of CuA and one CuB in Cytochrome a3). The cytochromes hold an oxygen molecule very tightly between the iron and copper ions until the oxygen is completely reduced. The reduced oxygen then picks up two hydrogen ions from the surrounding medium to make water (H2O). The removal of the hydrogen ions from the system contributes to the ion gradient used in the process of chemiosmosis.

Chemiosmosis

In chemiosmosis, the free energy from the series of red/ox reactions just described is used to pump protons across the membrane. The uneven distribution of H+ ions across the membrane establishes both concentration and electrical gradients (thus, an electrochemical gradient), owing to the proton's positive charge and their aggregation on one side of the membrane.

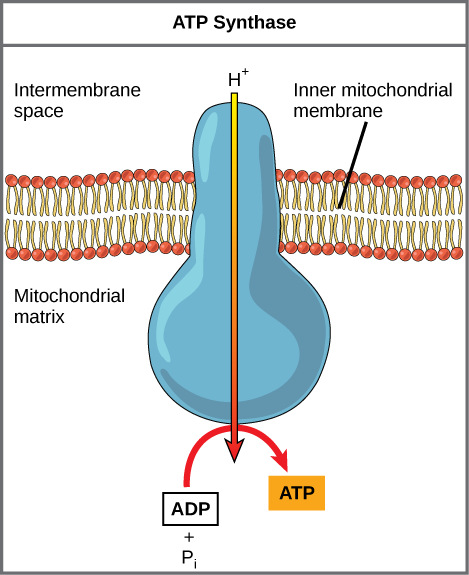

If the membrane were open to diffusion by protons, the ions would tend to diffuse back across into the matrix, driven by their electrochemical gradient. Ions, however, cannot diffuse through the nonpolar regions of phospholipid membranes without the aid of ion channels. Similarly, protons in the intermembrane space can only traverse the inner mitochondrial membrane through an integral membrane protein called ATP synthase (depicted below). This complex protein acts as a tiny generator, turned by transfer of energy mediated by protons moving down their electrochemical gradient. The movement of this molecular machine (enzyme) serves to lower the activation energy of reaction and couples the exergonic transfer of energy associated with the movement of protons down their electrochemical gradient to the endergonic addition of a phosphate to ADP, forming ATP.

Figure 3. ATP synthase is a complex, molecular machine that uses a proton (H+) gradient to form ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi).

Credit: modification of work by Klaus Hoffmeier

Note: possible discussion

Dinitrophenol (DNP) is a small chemical that serves to uncouple the flow of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane to the ATP synthase, and thus the synthesis of ATP. DNP makes the membrane leaky to protons. It was used until 1938 as a weight-loss drug. What effect would you expect DNP to have on the difference in pH across both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane? Why do you think this might be an effective weight-loss drug? Why might it be dangerous?

In healthy cells, chemiosmosis (depicted below) is used to generate 90 percent of the ATP made during aerobic glucose catabolism; it is also the method used in the light reactions of photosynthesis to harness the energy of sunlight in the process of photophosphorylation. Recall that the production of ATP using the process of chemiosmosis in mitochondria is called oxidative phosphorylation and that a similar process can occur in the membranes of bacterial and archaeal cells. The overall result of these reactions is the production of ATP from the energy of the electrons removed originally from a reduced organic molecule like glucose. In the aerobic example, these electrons ultimatel reduce oxygen and thereby create water.

Figure 4. In oxidative phosphorylation, the pH gradient formed by the electron transport chain is used by ATP synthase to form ATP in a Gram-bacteria.

Helpful link: How ATP is made from ATP synthase

Note: possible discussion

Cyanide inhibits cytochrome c oxidase, a component of the electron transport chain. If cyanide poisoning occurs, would you expect the pH of the intermembrane space to increase or decrease? What effect would cyanide have on ATP synthesis?

A Hypothesis for How ETC May Have Evolved

A proposed link between SLP/fermentation and the evolution of ETCs:

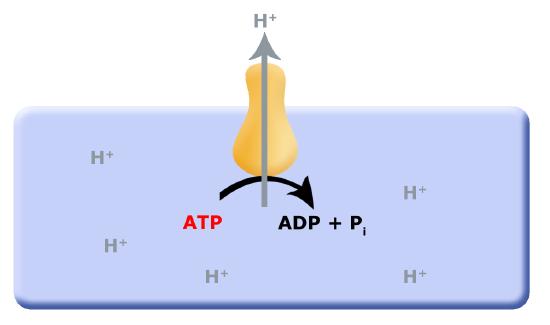

In a previous discussion of energy metabolism, we explored substrate level phosphorylation (SLP) and fermentation reactions. One of the questions in the discussion points for that discussion was: what are the short- and long-term consequences of SLP to the environment? We discussed how cells needed to co-evolve mechanisms in order to remove protons from the cytosol (interior of the cell), which led to the evolution of the F0F1-ATPase, a multi-subunit enzyme that translocates protons from the inside of the cell to the outside of the cell by hydrolyzing ATP, as shown below in the first picture below. This arrangement works as long as small reduced organic molecules are freely available, making SLP and fermentation advantageous. However, as these biological processes continue, the small reduced organic molecules begin to be used up, and their concentration decreases; this puts a demand on cells to be more efficient.

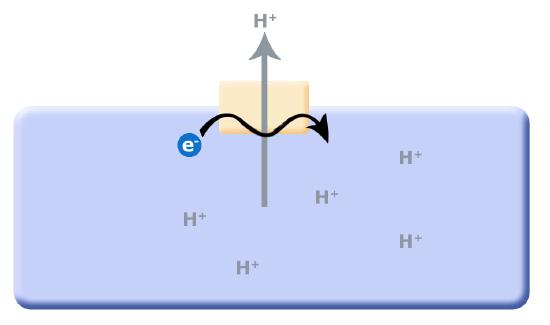

One source of potential "ATP waste" is in the removal of protons from the cell's cytosol; organisms that could find other mechanisms to expel accumulating protons while still preserving ATP could have a selective advantage. It is hypothesized that this selective evolutionary pressure potentially led to the evolution of the first membrane-bound proteins that used red/ox reactions as their energy source (depicted in second picture) to pump the accumulating protons. Enzymes and enzyme complexes with these properties exist today in the form of the electron transport complexes like Complex I, the NADH dehydrogenase.

Figure 1. Proposed evolution of an ATP dependent proton translocator

Figure 2. As small reduced organic molecules become limited, organisms that can find alternative mechanisms to remove protons from the cytosol may have an advantage. The evolution of a proton translocator that uses red/ox reactions rather than ATP hydrolysis could substitute for the ATPase.

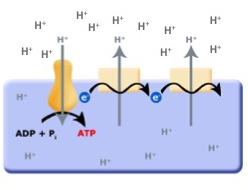

Continuing with this line of logic, if organisms evolved that could now use red/ox reactions to translocate protons across the membrane they would create a an electrochemical gradient, separating both charge (positive on the outside and negative on the inside; an electrical potential) and pH (low pH outside, higher pH inside). With excess protons on the outside of the cell membrane, and the F0F1-ATPase no longer consuming ATP to translocate protons, it is hypothesized that the electrochemical gradient could then be used to power the F0F1-ATPase "backwards" — that is, to form or produce ATP by using the energy in the charge/pH gradients set up by the red/ox pumps (as depicted below). This arrangement is called an electron transport chain (ETC).

Figure 3. The evolution of the ETC; the combination of the red/ox driven proton translocators coupled to the production of ATP by the F0F1-ATPase.

NoTE: Extended reading on the evolution of electron transport chains

If you're interested in the story of the evolution of electron transport chains, check out this more in-depth discussion of the topic at NCBI.