20.5: Esophagus and Stomach

- Page ID

- 53820

Esophagus and Stomach

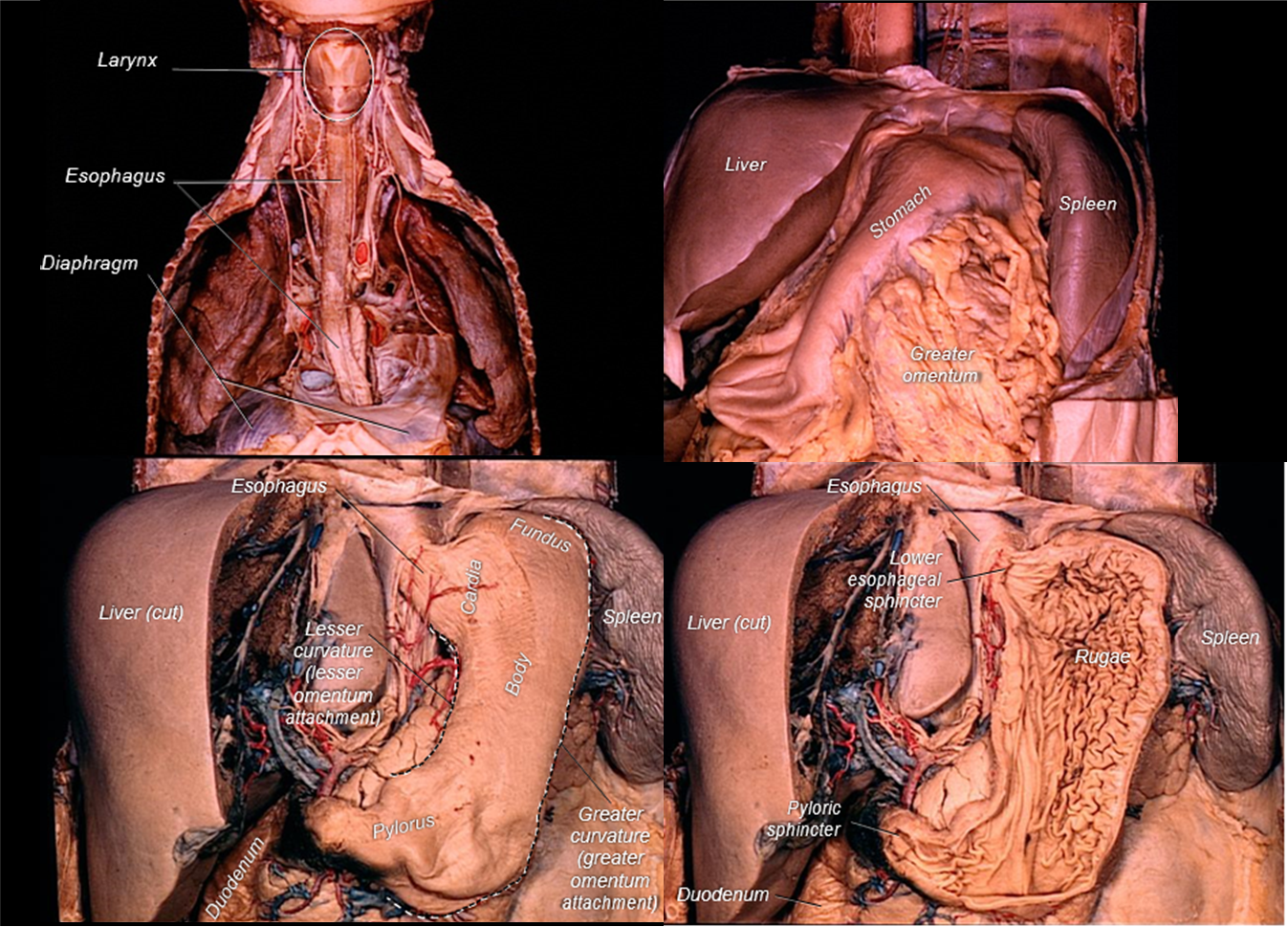

Above: Esophagus and stomach.

Sphincters, typically composed of a circular muscle, regulate the movement of digesting materials through the alimentary canal. The first sphincter the bolus passes through is the upper esophageal sphincter at the pharynx-esophageal transition. This sphincter prevents air from entering the esophagus and prevents reflux of materials within the esophagus into the pharynx. A lower esophageal sphincter is present where the esophagus meets the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes to let a bolus into the stomach and contracts to prevent regurgitation of stomach contents into the esophagus.

Above: Histology of the esophagus, magnified by 10x.

Above: A sharp transition in the mucosal epithelium, from stratified squamous moist (esophagus) to simple columnar (cardiac stomach), marks the transition of these two organs. Additional features of the stomach include the presence of gastric pits extending from the surface to the gastric glands in the lamina propria. This region can also be referred to as the gastro-esophageal junction. Tissue is magnified by 40x.

Muscularis externa is formed of inner circular and outer longitudinal layers. In the upper third of the esophagus, these layers are formed of skeletal muscle, which is involved with swallowing, a voluntary action. In the middle one-third, skeletal and smooth muscles are intermixed. In the lower one-third, only smooth muscle is present.

Above: Stomach.

The stomach is composed of four main parts: the cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. The cardiac region is where the esophagus meets the stomach. The fundus is a the dome-like region of the stomach, the main part is the body, and then the funnel-shaped area leading to the duodenum is called the pylorus. The pylorus leads to the pyloric sphincter that separates the stomach from the duodenum (first compartment of the small intestine). Inside the stomach are folds called rugae. When a large meal is eaten and the stomach is really full, the rugae stretch, becoming smoother to enable the stomach to stretch to accommodate the large meal. There are two curvatures of the stomach: the greater curvature and the lesser curvature. Unlike other regions of the alimentary canal, the stomach has three layers of muscularis externa (listed from inside out): oblique layer (fibers are diagonally-oriented), circular layer (fibers are oriented to form circle around the stomach), and longitudinal layer (fibers are oriented along the long axis of the stomach).

Above: Cadaver images showing the esophagus and stomach as well as other nearby abdominal organs.

The mucosal epithelium of the stomach is modified to form a sheet gland that invaginates into lamina propria, forming gastric pits. Gastric glands begin at the bases of these pits and extend to muscularis mucosae. The submucosa is composed of dense connective tissue. The gastric muscularis externa is composed of three layers of smooth muscle instead of the usual two; however, the additional internal oblique layer is inconsistently present. The stomach is covered on its exterior surface by a serosa because this organ protrudes into the peritoneal cavity.

Above: Histology of the stomach wall magnified by 10x.

The simple columnar epithelium lining the stomach is modified to form a sheet gland, with each cell in the sheet actively producing mucus that protects the stomach from its acidic environment. Mucin (a glycoprotein that mixes with water to form mucus) accumulates in the apex of each cell while the cytoplasm and nucleus are squeezed into the slender stem of the cell.

Above: The three regions of the stomach can be distinguished by the ratio of the length of the gastric pits to the length of the gastric glands. In the cardiac region (left), pits and glands are roughly equal in length; in the body and fundic regions (middle), the pits are much shorter than the glands; in the pyloric region, the pits are longer than the glands (right). Tissues are magnified by 100x.

The stomach continues digestion by secreting pepsin to aid in protein digestion, producing an acidic fluid, and churning via the thick muscularis externa. Hormones secreted by enteroendocrine cells modulate digestion.

Gastric pits contain specialized cells including goblet cells producing and secreting mucus, parietal cells producing and secreting hydrochloric acid, and G cells producing and secrete gastrin which stimulate the parietal cells to produce and secrete hydrochloric acid.

The gastric glands contain cells including parietal cells and G cells as well as chief cells and foveolar cells. Chief cells produce pepsinogen (pepsinogen is a zymogen and precursor to pepsin). Foveolar cells produce mucus. Mucus is essential for protecting the stomach tissues from the highly acidic environment of the stomach. Within the protective mucus, the stomach acids would eat away at the stomach tissues.

When the bolus transitions from the stomach to the small intestine, it is now called chyme.

Clinical Application: Gastric Bypass

Gastric bypass is a surgical procedure where the stomach is divided into a smaller upper portion and larger lower portion, and then both portions are reconnected to the small intestine. Because the functional volume of the usable portion of the stomach is significantly reduced, the physical and physiological response to consuming food is also altered. In effect, patients will feel full from consuming less food, and less calories will be absorbed by the body because a significant part of the gastrointestinal tract has been bypassed. The need to lose/control weight is the typical reason for gastric bypass surgery, and physicians often prescribe this surgery as treatment for patients fighting and struggling with morbid obesity.

Above: Diagram of gastric bypass.

Attributions

- "Anatomy 204L: Laboratory Manual (Second Edition)" by Ethan Snow, University of North Dakota is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- "Digital Histology" by Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology and the Office of Faculty Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine and the ALT Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- "Gray's Anatomy plates" by Henry Vandyke Carte is in the Public Domain

- "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014" by Blausen.com staff is licensed under