4.1: Understanding Evolution

- Page ID

- 69368

- Describe how the present-day theory of evolution was developed

- Define adaptation

- Explain convergent and divergent evolution

- Describe homologous and vestigial structures

- Discuss misconceptions about the theory of evolution

Evolution by natural selection describes a mechanism for how species change over time. That species change had been suggested and debated well before Darwin began to explore this idea. The view that species were static and unchanging was grounded in the writings of Plato, yet there were also ancient Greeks who expressed evolutionary ideas. In the eighteenth century, ideas about the evolution of animals were reintroduced by the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc Comte de Buffon who observed that various geographic regions have different plant and animal populations, even when the environments are similar. It was also accepted that there were extinct species.

During this time, James Hutton, a Scottish naturalist, proposed that geological change occurred gradually by the accumulation of small changes from processes operating like they are today over long periods of time. This contrasted with the predominant view that the geology of the planet was a consequence of catastrophic events occurring during a relatively brief past. Hutton’s view was popularized in the nineteenth century by the geologist Charles Lyell who became a friend to Darwin. Lyell’s ideas were influential on Darwin’s thinking: Lyell’s notion of the greater age of Earth gave more time for gradual change in species, and the process of change provided an analogy for gradual change in species. In the early nineteenth century, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a book that detailed a mechanism for evolutionary change. This mechanism is now referred to as an inheritance of acquired characteristics by which modifications in an individual are caused by its environment, or the use or disuse of a structure during its lifetime, could be inherited by its offspring and thus bring about change in a species. While this mechanism for evolutionary change was discredited, Lamarck’s ideas were an important influence on evolutionary thought.

Charles Darwin and Natural Selection

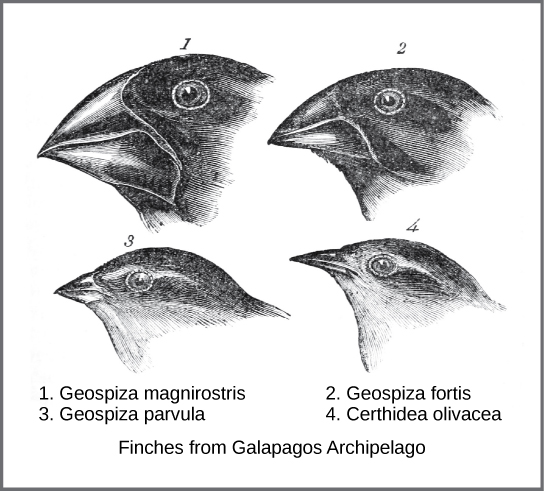

In the mid-nineteenth century, the actual mechanism for evolution was independently conceived of and described by two naturalists: Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Importantly, each naturalist spent time exploring the natural world on expeditions to the tropics. From 1831 to 1836, Darwin traveled around the world on H.M.S. Beagle, including stops in South America, Australia, and the southern tip of Africa. Wallace traveled to Brazil to collect insects in the Amazon rainforest from 1848 to 1852 and to the Malay Archipelago from 1854 to 1862. Darwin’s journey, like Wallace’s later journeys to the Malay Archipelago, included stops at several island chains, the last being the Galápagos Islands west of Ecuador. On these islands, Darwin observed species of organisms on different islands that were clearly similar, yet had distinct differences. For example, the ground finches inhabiting the Galápagos Islands comprised several species with a unique beak shape (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The species on the islands had a graded series of beak sizes and shapes with very small differences between the most similar. He observed that these finches closely resembled another finch species on the mainland of South America. Darwin imagined that the island species might be species modified from one of the original mainland species. Upon further study, he realized that the varied beaks of each finch helped the birds acquire a specific type of food. For example, seed-eating finches had stronger, thicker beaks for breaking seeds, and insect-eating finches had spear-like beaks for stabbing their prey.

Wallace and Darwin both observed similar patterns in other organisms and they independently developed the same explanation for how and why such changes could take place. Darwin called this mechanism natural selection. Natural selection, also known as “survival of the fittest,” is the more prolific reproduction of individuals with favorable traits that survive environmental change because of those traits; this leads to evolutionary change.

For example, a population of giant tortoises found in the Galapagos Archipelago was observed by Darwin to have longer necks than those that lived on other islands with dry lowlands. These tortoises were “selected” because they could reach more leaves and access more food than those with short necks. In times of drought when fewer leaves would be available, those that could reach more leaves had a better chance to eat and survive than those that couldn’t reach the food source. Consequently, long-necked tortoises would be more likely to be reproductively successful and pass the long-necked trait to their offspring. Over time, only long-necked tortoises would be present in the population.

Natural selection, Darwin argued, was an inevitable outcome of three principles that operated in nature. First, most characteristics of organisms are inherited, or passed from parent to offspring. Although no one, including Darwin and Wallace, knew how this happened at the time, it was a common understanding. Second, more offspring are produced than are able to survive, so resources for survival and reproduction are limited. The capacity for reproduction in all organisms outstrips the availability of resources to support their numbers. Thus, there is competition for those resources in each generation. Both Darwin and Wallace’s understanding of this principle came from reading an essay by the economist Thomas Malthus who discussed this principle in relation to human populations. Third, offspring vary among each other in regard to their characteristics and those variations are inherited. Darwin and Wallace reasoned that offspring with inherited characteristics which allow them to best compete for limited resources will survive and have more offspring than those individuals with variations that are less able to compete. Because characteristics are inherited, these traits will be better represented in the next generation. This will lead to change in populations over generations in a process that Darwin called descent with modification. Ultimately, natural selection leads to greater adaptation of the population to its local environment; it is the only mechanism known for adaptive evolution.

Papers by Darwin and Wallace (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) presenting the idea of natural selection were read together in 1858 before the Linnean Society in London. The following year Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, was published. His book outlined in considerable detail his arguments for evolution by natural selection.

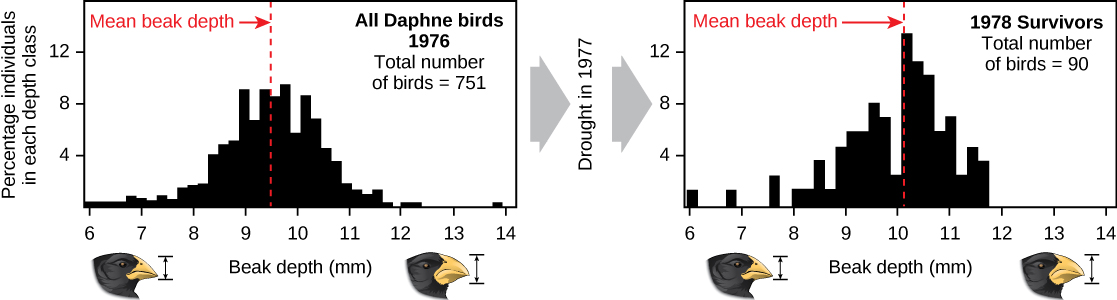

Demonstrations of evolution by natural selection are time consuming and difficult to obtain. One of the best examples has been demonstrated in the very birds that helped to inspire Darwin’s theory: the Galápagos finches. Peter and Rosemary Grant and their colleagues have studied Galápagos finch populations every year since 1976 and have provided important demonstrations of natural selection. The Grants found changes from one generation to the next in the distribution of beak shapes with the medium ground finch on the Galápagos island of Daphne Major. The medium ground finch feeds on seeds. The birds have inherited variation in the bill shape with some birds having wide deep bills and others having thinner bills. Large-billed birds feed more efficiently on large, hard seeds, whereas smaller billed birds feed more efficiently on small, soft seeds. During 1977, a drought period altered vegetation on the island. After this period, the number of seeds declined dramatically: the decline in small, soft seeds was greater than the decline in large, hard seeds. The large-billed birds were able to survive better than the small-billed birds the following year. The year following the drought when the Grants measured beak sizes in the much-reduced population, they found that the average bill size was larger ((Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\))). This was clear evidence for natural selection (differences in survival) of bill size caused by the availability of seeds. The Grants had studied the inheritance of bill sizes and knew that the surviving large-billed birds would tend to produce offspring with larger bills, so the selection would lead to evolution of bill size.

((Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\))): A drought on the Galápagos island of Daphne Major in 1977 reduced the number of small seeds available to finches, causing many of the small-beaked finches to die. This caused an increase in the finches’ average beak size between 1976 and 1978.

During a period in which rainfall was higher than normal because of an El Niño, the large hard seeds that large-billed birds ate were reduced in number; however, there was an abundance of the small soft seeds which the small-billed birds ate. Therefore, survival and reproduction were much better in the following years for the small-billed birds. In the years following this El Niño, the Grants measured beak sizes in the population and found that the average bill size was smaller. Since bill size is an inherited trait, parents with smaller bills had more offspring and the size of bills had evolved to be smaller. As conditions improved in 1987 and larger seeds became more available, the trend toward smaller average bill size ceased. Subsequent studies by the Grants have demonstrated selection on and evolution of bill size in this species in response to changing conditions on the island. The evolution has occurred both to larger bills, as in this case, and to smaller bills when large seeds became rare.

Many people hike, explore caves, scuba dive, or climb mountains for recreation. People often participate in these activities hoping to see wildlife. Experiencing the outdoors can be incredibly enjoyable and invigorating. What if your job was to be outside in the wilderness? Field biologists by definition work outdoors in the “field.” The term field in this case refers to any location outdoors, even under water. A field biologist typically focuses research on a certain species, group of organisms, or a single habitat (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

One objective of many field biologists includes discovering new species that have never been recorded. Not only do such findings expand our understanding of the natural world, but they also lead to important innovations in fields such as medicine and agriculture. Plant and microbial species, in particular, can reveal new medicinal and nutritive knowledge. Other organisms can play key roles in ecosystems or be considered rare and in need of protection. When discovered, these important species can be used as evidence for environmental regulations and laws.

Processes and Patterns of Evolution

Natural selection can only take place if there is variation, or differences, among individuals in a population. Importantly, these differences must have some genetic basis; otherwise, the selection will not lead to change in the next generation. This is critical because variation among individuals can be caused by non-genetic reasons such as an individual being taller because of better nutrition rather than different genes.

Genetic diversity in a population comes from two main mechanisms: mutation and sexual reproduction. Mutation, a change in DNA, is the ultimate source of new alleles, or new genetic variation in any population. The genetic changes caused by mutation can have one of three outcomes on the phenotype. A mutation affects the phenotype of the organism in a way that gives it reduced fitness—lower likelihood of survival or fewer offspring. A mutation may produce a phenotype with a beneficial effect on fitness. And, many mutations will also have no effect on the fitness of the phenotype; these are called neutral mutations. Mutations may also have a whole range of effect sizes on the fitness of the organism that expresses them in their phenotype, from a small effect to a great effect. Sexual reproduction also leads to genetic diversity: when two parents reproduce, unique combinations of alleles assemble to produce the unique genotypes and thus phenotypes in each of the offspring.

A heritable trait that helps the survival and reproduction of an organism in its present environment is called an adaptation. Scientists describe groups of organisms becoming adapted to their environment when a change in the range of genetic variation occurs over time that increases or maintains the “fit” of the population to its environment. The webbed feet of platypuses are an adaptation for swimming. The snow leopards’ thick fur is an adaptation for living in the cold. The cheetahs’ fast speed is an adaptation for catching prey.

Whether or not a trait is favorable depends on the environmental conditions at the time. The same traits are not always selected because environmental conditions can change. For example, consider a species of plant that grew in a moist climate and did not need to conserve water. Large leaves were selected because they allowed the plant to obtain more energy from the sun. Large leaves require more water to maintain than small leaves, and the moist environment provided favorable conditions to support large leaves. After thousands of years, the climate changed, and the area no longer had excess water. The direction of natural selection shifted so that plants with small leaves were selected because those populations were able to conserve water to survive the new environmental conditions.

The evolution of species has resulted in enormous variation in form and function. Sometimes, evolution gives rise to groups of organisms that become tremendously different from each other. When two species evolve in diverse directions from a common point, it is called divergent evolution. Such divergent evolution can be seen in the forms of the reproductive organs of flowering plants which share the same basic anatomies; however, they can look very different as a result of selection in different physical environments and adaptation to different kinds of pollinators (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

In other cases, similar phenotypes evolve independently in distantly related species. For example, flight has evolved in both bats and insects, and they both have structures we refer to as wings, which are adaptations to flight. However, the wings of bats and insects have evolved from very different original structures. This phenomenon is called convergent evolution, where similar traits evolve independently in species that do not share a recent common ancestry. The two species came to the same function, flying, but did so separately from each other.

These physical changes occur over enormous spans of time and help explain how evolution occurs. Natural selection acts on individual organisms, which in turn can shape an entire species. Although natural selection may work in a single generation on an individual, it can take thousands or even millions of years for the genotype of an entire species to evolve. It is over these large time spans that life on earth has changed and continues to change.

Evidence of Evolution

The evidence for evolution is compelling and extensive. Looking at every level of organization in living systems, biologists see the signature of past and present evolution. Darwin dedicated a large portion of his book, On the Origin of Species, to identifying patterns in nature that were consistent with evolution, and since Darwin, our understanding has become clearer and broader.

Fossils

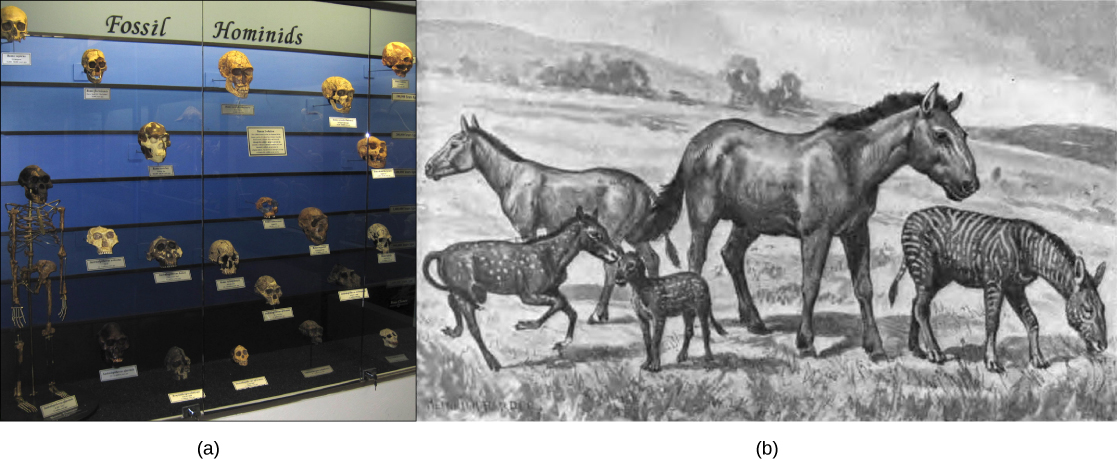

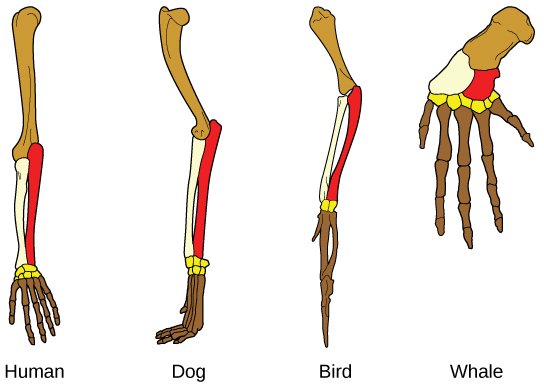

Fossils provide solid evidence that organisms from the past are not the same as those found today, and fossils show a progression of evolution. Scientists determine the age of fossils and categorize them from all over the world to determine when the organisms lived relative to each other. The resulting fossil record tells the story of the past and shows the evolution of form over millions of years (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). For example, scientists have recovered highly detailed records showing the evolution of humans and horses (Figure \(\PageIndex{6-7}\)). The whale flipper shares a similar morphology to appendages of birds and mammals (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) indicating that these species share a common ancestor.

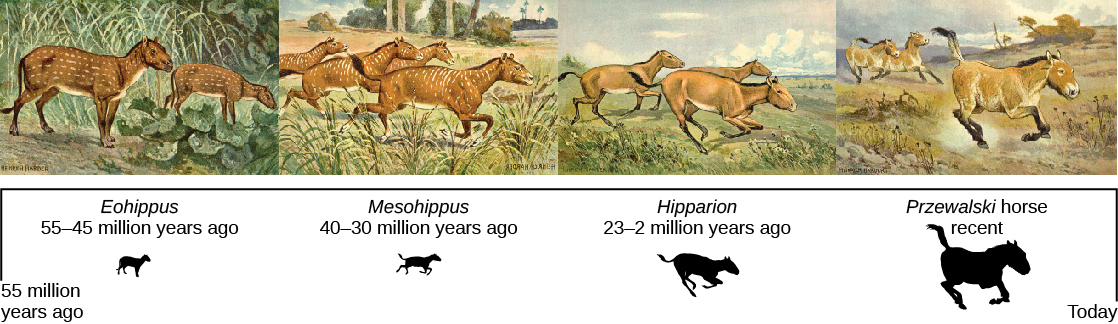

The fossil record of horses in North America is especially rich and many contain transition fossils: those showing intermediate anatomy between earlier and later forms (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). The fossil record extends back to a dog-like ancestor some 55 million years ago that gave rise to the first horse-like species 55 to 42 million years ago in the genus Eohippus. The series of fossils tracks the change in anatomy resulting from a gradual drying trend that changed the landscape from a forested one to a prairie. Successive fossils show the evolution of teeth shapes and foot and leg anatomy to a grazing habit, with adaptations for escaping predators, for example in species of Mesohippus found from 40 to 30 million years ago. Later species showed gains in size, such as those of Hipparion, which existed from about 23 to 2 million years ago. The fossil record shows several adaptive radiations in the horse lineage, which is now much reduced to only one genus, Equus, with several species.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): This illustration shows an artist’s renderings of these species derived from fossils of the evolutionary history of the horse and its ancestors. The species depicted are only four from a very diverse lineage that contains many branches, dead ends, and adaptive radiations. One of the trends, depicted here is the evolutionary tracking of a drying climate and increase in prairie versus forest habitat reflected in forms that are more adapted to grazing and predator escape through running. Przewalski's horse is one of a few living species of horse.

Anatomy and Embryology

Another type of evidence for evolution is the presence of structures in organisms that share the same basic form. For example, the bones in the appendages of a human, dog, bird, and whale all share the same overall construction (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). That similarity results from their origin in the appendages of a common ancestor. Over time, evolution led to changes in the shapes and sizes of these bones in different species, but they have maintained the same overall layout, evidence of descent from a common ancestor. Scientists call these synonymous parts homologous structures. Some structures exist in organisms that have no apparent function at all, and appear to be residual parts from a past ancestor. For example, some snakes have pelvic bones despite having no legs because they descended from reptiles that did have legs. These unused structures without function are called vestigial structures. Other examples of vestigial structures are wings on flightless birds (which may have other functions), leaves on some cacti, traces of pelvic bones in whales, and the sightless eyes of cave animals.

Visit this interactive site to guess which bones structures are homologous and which are analogous, and see examples of evolutionary adaptations to illustrate these concepts.

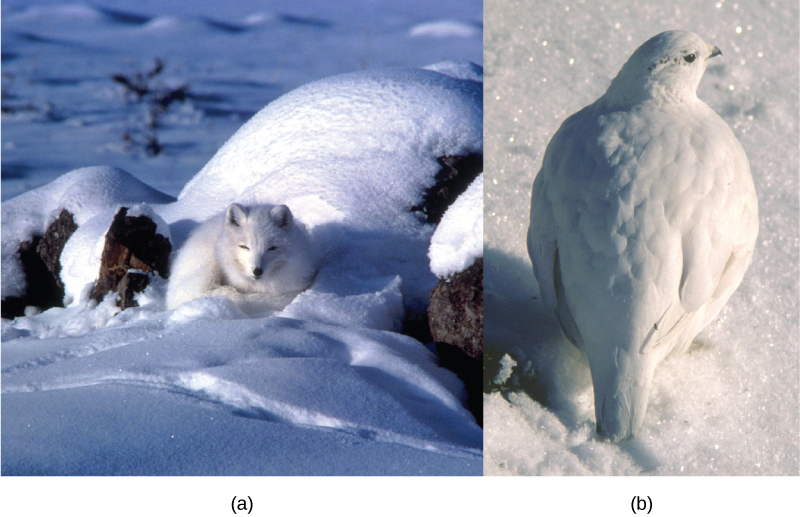

Another evidence of evolution is the convergence of form in organisms that share similar environments. For example, species of unrelated animals, such as the arctic fox and ptarmigan, living in the arctic region have been selected for seasonal white phenotypes during winter to blend with the snow and ice (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). These similarities occur not because of common ancestry, but because of similar selection pressures—the benefits of not being seen by predators.

Embryology, the study of the development of the anatomy of an organism to its adult form, also provides evidence of relatedness between now widely divergent groups of organisms. Mutational tweaking in the embryo can have such magnified consequences in the adult that embryo formation tends to be conserved. As a result, structures that are absent in some groups often appear in their embryonic forms and disappear by the time the adult or juvenile form is reached. For example, all vertebrate embryos, including humans, exhibit gill slits and tails at some point in their early development. These disappear in the adults of terrestrial groups but are maintained in adult forms of aquatic groups such as fish and some amphibians. Great ape embryos, including humans, have a tail structure during their development that is lost by the time of birth.

Biogeography

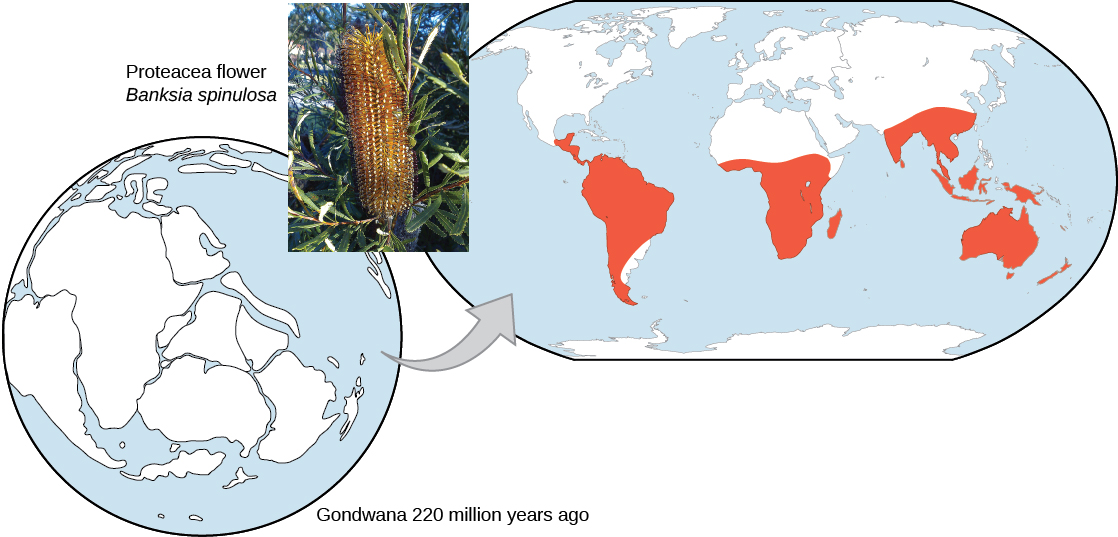

The geographic distribution of organisms on the planet follows patterns that are best explained by evolution in conjunction with the movement of tectonic plates over geological time. Broad groups that evolved before the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea (about 200 million years ago) are distributed worldwide. Groups that evolved since the breakup appear uniquely in regions of the planet, such as the unique flora and fauna of northern continents that formed from the supercontinent Laurasia and of the southern continents that formed from the supercontinent Gondwana. The presence of members of the plant family Proteaceae in Australia, southern Africa, and South America is best explained by their presence prior to the southern supercontinent Gondwana breaking up (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)).

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): The Proteacea family of plants evolved before the supercontinent Gondwana broke up. Today, members of this plant family are found throughout the southern hemisphere (shown in red). (credit “Proteacea flower”: modification of work by “dorofofoto”/Flickr)

The great diversification of marsupials in Australia and the absence of other mammals reflect Australia’s long isolation. Australia has an abundance of endemic species—species found nowhere else—which is typical of islands whose isolation by expanses of water prevents species from migrating. Over time, these species diverge evolutionarily into new species that look very different from their ancestors that may exist on the mainland. The marsupials of Australia, the finches on the Galápagos, and many species on the Hawaiian Islands are all unique to their one point of origin, yet they display distant relationships to ancestral species on mainlands.

Molecular Biology

Like anatomical structures, the structures of the molecules of life reflect descent with modification. Evidence of a common ancestor for all of life is reflected in the universality of DNA as the genetic material and in the near universality of the genetic code and the machinery of DNA replication and expression. Fundamental divisions in life between the three domains are reflected in major structural differences in otherwise conservative structures such as the components of ribosomes and the structures of membranes. In general, the relatedness of groups of organisms is reflected in the similarity of their DNA sequences—exactly the pattern that would be expected from descent and diversification from a common ancestor.

DNA sequences have also shed light on some of the mechanisms of evolution. For example, it is clear that the evolution of new functions for proteins commonly occurs after gene duplication events that allow the free modification of one copy by mutation, selection, or drift (changes in a population’s gene pool resulting from chance), while the second copy continues to produce a functional protein.

Population Genetics

Recall that a gene for a particular character may have several variants, or alleles, that code for different traits associated with that character. For example, in the ABO blood type system in humans, three alleles determine the particular blood-type protein on the surface of red blood cells. Each individual in a population of diploid organisms can only carry two alleles for a particular gene, but more than two may be present in the individuals that make up the population. Mendel followed alleles as they were inherited from parent to offspring. In the early twentieth century, biologists began to study what happens to all the alleles in a population in a field of study known as population genetics.

Until now, we have defined evolution as a change in the characteristics of a population of organisms, but behind that phenotypic change is genetic change. In population genetic terms, evolution is defined as a change in the frequency of an allele in a population. Using the ABO system as an example, the frequency of one of the alleles, IA, is the number of copies of that allele divided by all the copies of the ABO gene in the population. For example, a study in Jordan found a frequency of IA to be 26.1 percent.2 The IB, I0 alleles made up 13.4 percent and 60.5 percent of the alleles respectively, and all of the frequencies add up to 100 percent. A change in this frequency over time would constitute evolution in the population.

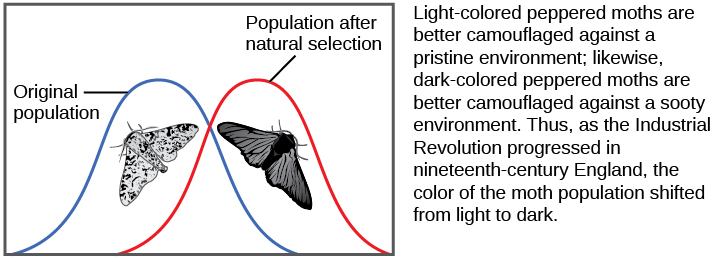

There are several ways the allele frequencies of a population can change. One of those ways is natural selection. If a given allele confers a phenotype that allows an individual to have more offspring that survive and reproduce, that allele, by virtue of being inherited by those offspring, will be in greater frequency in the next generation. Since allele frequencies always add up to 100 percent, an increase in the frequency of one allele always means a corresponding decrease in one or more of the other alleles. Highly beneficial alleles may, over a very few generations, become “fixed” in this way, meaning that every individual of the population will carry the allele. Similarly, detrimental alleles may be swiftly eliminated from the gene pool, the sum of all the alleles in a population. Part of the study of population genetics is tracking how selective forces change the allele frequencies in a population over time, which can give scientists clues regarding the selective forces that may be operating on a given population. The studies of changes in wing coloration in the peppered moth from mottled white to dark in response to soot-covered tree trunks and then back to mottled white when factories stopped producing so much soot is a classic example of studying evolution in natural populations (Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)).

In the early twentieth century, English mathematician Godfrey Hardy and German physician Wilhelm Weinberg independently provided an explanation for a somewhat counterintuitive concept. Hardy’s original explanation was in response to a misunderstanding as to why a “dominant” allele, one that masks a recessive allele, should not increase in frequency in a population until it eliminated all the other alleles. The question resulted from a common confusion about what “dominant” means, but it forced Hardy, who was not even a biologist, to point out that if there are no factors that affect an allele frequency those frequencies will remain constant from one generation to the next. This principle is now known as the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The theory states that a population’s allele and genotype frequencies are inherently stable—unless some kind of evolutionary force is acting on the population, the population would carry the same alleles in the same proportions generation after generation. Individuals would, as a whole, look essentially the same and this would be unrelated to whether the alleles were dominant or recessive. The four most important evolutionary forces, which will disrupt the equilibrium, are natural selection, mutation, genetic drift, and migration into or out of a population. A fifth factor, nonrandom mating, will also disrupt the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium but only by shifting genotype frequencies, not allele frequencies. In nonrandom mating, individuals are more likely to mate with like individuals (or unlike individuals) rather than at random. Since nonrandom mating does not change allele frequencies, it does not cause evolution directly. Natural selection has been described. Mutation creates one allele out of another one and changes an allele’s frequency by a small, but continuous amount each generation. Each allele is generated by a low, constant mutation rate that will slowly increase the allele’s frequency in a population if no other forces act on the allele. If natural selection acts against the allele, it will be removed from the population at a low rate leading to a frequency that results from a balance between selection and mutation. This is one reason that genetic diseases remain in the human population at very low frequencies. If the allele is favored by selection, it will increase in frequency. Genetic drift causes random changes in allele frequencies when populations are small. Genetic drift can often be important in evolution, as discussed in the next section. Finally, if two populations of a species have different allele frequencies, migration of individuals between them will cause frequency changes in both populations. As it happens, there is no population in which one or more of these processes are not operating, so populations are always evolving, and the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium will never be exactly observed. However, the Hardy-Weinberg principle gives scientists a baseline expectation for allele frequencies in a non-evolving population to which they can compare evolving populations and thereby infer what evolutionary forces might be at play. The population is evolving if the frequencies of alleles or genotypes deviate from the value expected from the Hardy-Weinberg principle.

Darwin identified a special case of natural selection that he called sexual selection. Sexual selection affects an individual’s ability to mate and thus produce offspring, and it leads to the evolution of dramatic traits that often appear maladaptive in terms of survival but persist because they give their owners greater reproductive success. Sexual selection occurs in two ways: through male–male competition for mates and through female selection of mates. Male–male competition takes the form of conflicts between males, which are often ritualized, but may also pose significant threats to a male’s survival. Sometimes the competition is for territory, with females more likely to mate with males with higher quality territories. Female choice occurs when females choose a male based on a particular trait, such as feather colors, the performance of a mating dance, or the building of an elaborate structure. In some cases male–male competition and female choice combine in the mating process. In each of these cases, the traits selected for, such as fighting ability or feather color and length, become enhanced in the males. In general, it is thought that sexual selection can proceed to a point at which natural selection against a character’s further enhancement prevents its further evolution because it negatively impacts the male’s ability to survive. For example, colorful feathers or an elaborate display make the male more obvious to predators.

Genetic Drift

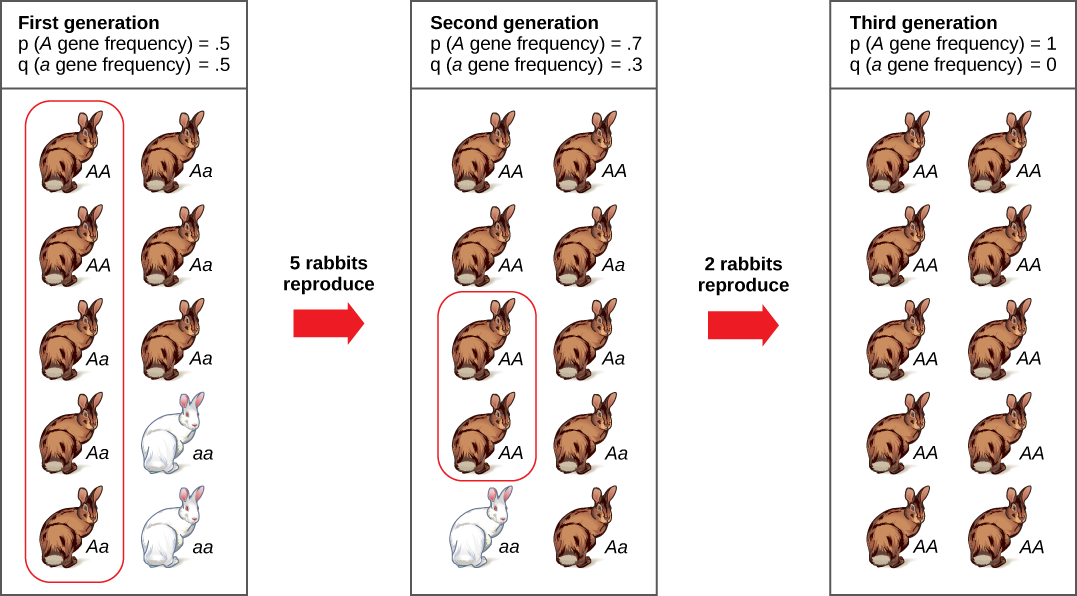

Another way a population’s allele frequencies can change is genetic drift (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)), which is simply the effect of chance. Genetic drift is most important in small populations. Drift would be completely absent in a population with infinite individuals, but, of course, no population is this large. Genetic drift occurs because the alleles in an offspring generation are a random sample of the alleles in the parent generation. Alleles may or may not make it into the next generation due to chance events including mortality of an individual, events affecting finding a mate, and even the events affecting which gametes end up in fertilizations. If one individual in a population of ten individuals happens to die before it leaves any offspring to the next generation, all of its genes—a tenth of the population’s gene pool—will be suddenly lost. In a population of 100, that 1 individual represents only 1 percent of the overall gene pool; therefore, it has much less impact on the population’s genetic structure and is unlikely to remove all copies of even a relatively rare allele.

Imagine a population of ten individuals, half with allele A and half with allele a (the individuals are haploid). In a stable population, the next generation will also have ten individuals. Choose that generation randomly by flipping a coin ten times and let heads be A and tails be a. It is unlikely that the next generation will have exactly half of each allele. There might be six of one and four of the other, or some different set of frequencies. Thus, the allele frequencies have changed and evolution has occurred. A coin will no longer work to choose the next generation (because the odds are no longer one half for each allele). The frequency in each generation will drift up and down on what is known as a random walk until at one point either all A or all a are chosen and that allele is fixed from that point on. This could take a very long time for a large population. This simplification is not very biological, but it can be shown that real populations behave this way. The effect of drift on frequencies is greater the smaller a population is. Its effect is also greater on an allele with a frequency far from one half. Drift will influence every allele, even those that are being naturally selected.

Do you think genetic drift would happen more quickly on an island or on the mainland?

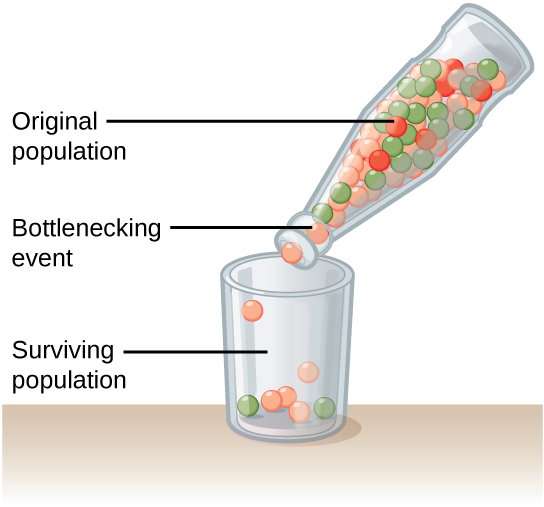

Genetic drift can also be magnified by natural or human-caused events, such as a disaster that randomly kills a large portion of the population, which is known as the bottleneck effect that results in a large portion of the genome suddenly being wiped out (Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)). In one fell swoop, the genetic structure of the survivors becomes the genetic structure of the entire population, which may be very different from the pre-disaster population. The disaster must be one that kills for reasons unrelated to the organism’s traits, such as a hurricane or lava flow. A mass killing caused by unusually cold temperatures at night, is likely to affect individuals differently depending on the alleles they possess that confer cold hardiness.

Another scenario in which populations might experience a strong influence of genetic drift is if some portion of the population leaves to start a new population in a new location, or if a population gets divided by a physical barrier of some kind. In this situation, those individuals are unlikely to be representative of the entire population which results in the founder effect. The founder effect occurs when the genetic structure matches that of the new population’s founding fathers and mothers. The founder effect is believed to have been a key factor in the genetic history of the Afrikaner population of Dutch settlers in South Africa, as evidenced by mutations that are common in Afrikaners but rare in most other populations. This is likely due to a higher-than-normal proportion of the founding colonists, which were a small sample of the original population, carried these mutations. As a result, the population expresses unusually high incidences of Huntington’s disease (HD) and Fanconi anemia (FA), a genetic disorder known to cause bone marrow and congenital abnormalities, and even cancer.3

Visit this site to learn more about genetic drift and to run simulations of allele changes caused by drift.

Gene Flow

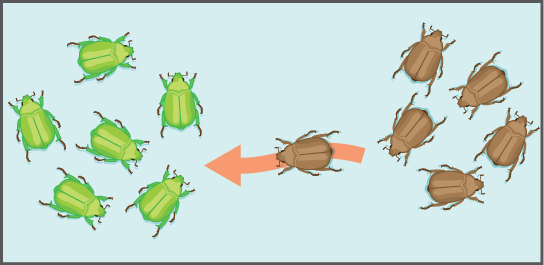

Another important evolutionary force is gene flow, or the flow of alleles in and out of a population resulting from the migration of individuals or gametes (Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)). While some populations are fairly stable, others experience more flux. Many plants, for example, send their seeds far and wide, by wind or in the guts of animals; these seeds may introduce alleles common in the source population to a new population in which they are rare.

Misconceptions of Evolution

Although the theory of evolution generated some controversy when it was first proposed, it was almost universally accepted by biologists, particularly younger biologists, within 20 years after publication of On the Origin of Species. Nevertheless, the theory of evolution is a difficult concept and misconceptions about how it works abound

This site addresses some of the main misconceptions associated with the theory of evolution.

Evolution Is Just a Theory

Critics of the theory of evolution dismiss its importance by purposefully confounding the everyday usage of the word “theory” with the way scientists use the word. In science, a “theory” is understood to be a body of thoroughly tested and verified explanations for a set of observations of the natural world. Scientists have a theory of the atom, a theory of gravity, and the theory of relativity, each of which describes understood facts about the world. In the same way, the theory of evolution describes facts about the living world. As such, a theory in science has survived significant efforts to discredit it by scientists. In contrast, a “theory” in common vernacular is a word meaning a guess or suggested explanation; this meaning is more akin to the scientific concept of “hypothesis.” When critics of evolution say evolution is “just a theory,” they are implying that there is little evidence supporting it and that it is still in the process of being rigorously tested. This is a mischaracterization.

Individuals Evolve

Evolution is the change in genetic composition of a population over time, specifically over generations, resulting from differential reproduction of individuals with certain alleles. Individuals do change over their lifetime, obviously, but this is called development and involves changes programmed by the set of genes the individual acquired at birth in coordination with the individual’s environment. When thinking about the evolution of a characteristic, it is probably best to think about the change of the average value of the characteristic in the population over time. For example, when natural selection leads to bill-size change in medium-ground finches in the Galápagos, this does not mean that individual bills on the finches are changing. If one measures the average bill size among all individuals in the population at one time and then measures the average bill size in the population several years later, this average value will be different as a result of evolution. Although some individuals may survive from the first time to the second, they will still have the same bill size; however, there will be many new individuals that contribute to the shift in average bill size.

Evolution Explains the Origin of Life

It is a common misunderstanding that evolution includes an explanation of life’s origins. Conversely, some of the theory’s critics believe that it cannot explain the origin of life. The theory does not try to explain the origin of life. The theory of evolution explains how populations change over time and how life diversifies the origin of species. It does not shed light on the beginnings of life including the origins of the first cells, which is how life is defined. The mechanisms of the origin of life on Earth are a particularly difficult problem because it occurred a very long time ago, and presumably it just occurred once. Importantly, biologists believe that the presence of life on Earth precludes the possibility that the events that led to life on Earth can be repeated because the intermediate stages would immediately become food for existing living things.

However, once a mechanism of inheritance was in place in the form of a molecule like DNA either within a cell or pre-cell, these entities would be subject to the principle of natural selection. More effective reproducers would increase in frequency at the expense of inefficient reproducers. So while evolution does not explain the origin of life, it may have something to say about some of the processes operating once pre-living entities acquired certain properties.

Organisms Evolve on Purpose

Statements such as “organisms evolve in response to a change in an environment” are quite common, but such statements can lead to two types of misunderstandings. First, the statement must not be understood to mean that individual organisms evolve. The statement is shorthand for “a population evolves in response to a changing environment.” However, a second misunderstanding may arise by interpreting the statement to mean that the evolution is somehow intentional. A changed environment results in some individuals in the population, those with particular phenotypes, benefiting and therefore producing proportionately more offspring than other phenotypes. This results in change in the population if the characteristics are genetically determined.

It is also important to understand that the variation that natural selection works on is already in a population and does not arise in response to an environmental change. For example, applying antibiotics to a population of bacteria will, over time, select a population of bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. The resistance, which is caused by a gene, did not arise by mutation because of the application of the antibiotic. The gene for resistance was already present in the gene pool of the bacteria, likely at a low frequency. The antibiotic, which kills the bacterial cells without the resistance gene, strongly selects individuals that are resistant, since these would be the only ones that survived and divided. Experiments have demonstrated that mutations for antibiotic resistance do not arise as a result of antibiotic.

In a larger sense, evolution is not goal directed. Species do not become “better” over time; they simply track their changing environment with adaptations that maximize their reproduction in a particular environment at a particular time. Evolution has no goal of making faster, bigger, more complex, or even smarter species, despite the commonness of this kind of language in popular discourse. What characteristics evolve in a species are a function of the variation present and the environment, both of which are constantly changing in a non-directional way. What trait is fit in one environment at one time may well be fatal at some point in the future. This holds equally well for a species of insect as it does the human species.

References

- 1 Charles Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N, 2nd. ed. (London: John Murray, 1860), http://www.archive.org/details/journalofresea00darw.

- 2 Sahar S. Hanania, Dhia S. Hassawi, and Nidal M. Irshaid, “Allele Frequency and Molecular Genotypes of ABO Blood Group System in a Jordanian Population,” Journal of Medical Sciences 7 (2007): 51-58, doi:10.3923/jms.2007.51.58

- 1 A. J. Tipping et al., “Molecular and Genealogical Evidence for a Founder Effect in Fanconi Anemia Families of the Afrikaner Population of South Africa,” PNAS 98, no. 10 (2001): 5734-5739, doi: 10.1073/pnas.091402398.

Contributors and Attributions

- Modified from the Original by Kyle Whittinghill (University of Pittsburgh)

Connie Rye (East Mississippi Community College), Robert Wise (University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh), Vladimir Jurukovski (Suffolk County Community College), Jean DeSaix (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Jung Choi (Georgia Institute of Technology), Yael Avissar (Rhode Island College) among other contributing authors. Original content by OpenStax (CC BY 4.0; Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72...f21b5eabd@9.87).

- Samantha Fowler (Clayton State University), Rebecca Roush (Sandhills Community College), James Wise (Hampton University). Original content by OpenStax (CC BY 4.0; Access for free at https://cnx.org/contents/b3c1e1d2-83...4-e119a8aafbdd).

- 18.1: Understanding Evolution by OpenStax, is licensed CC BY

- 11.3 Evidence of Evolution by OpenStax, is licensed CC BY

- 11.2 Mechanisms of Evolution by OpenStax, is licensed CC BY

- 11.1: Discovering How Populations Change by OpenStax, is licensed CC BY