6.7: Viral Infections of the Reproductive System

- Page ID

- 79549

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common viruses that cause infections of the reproductive system

- Compare the major characteristics of specific viral diseases affecting the reproductive system

Several viruses can cause serious problems for the human reproductive system. Most of these viral infections are incurable, increasing the risk of persistent sexual transmission. In addition, such viral infections are very common in the United States. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common STI in the country, with an estimated prevalence of 79.1 million infections in 2008; herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) is the next most prevalent STI at 24.1 million infections.1 In this section, we will examine these and other major viral infections of the reproductive system.

Genital Herpes

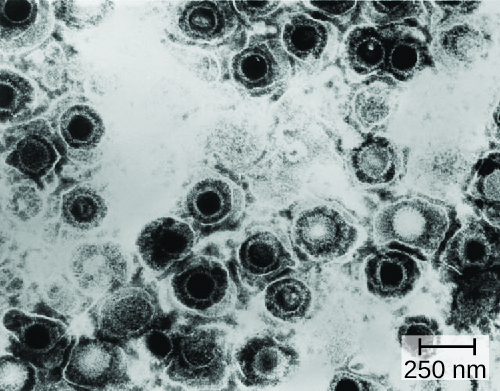

Genital herpes is a common condition caused by the herpes simplex virus (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), an enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus that is classified into two distinct types. Herpes simplex virus has several virulence factors, including infected cell protein (ICP) 34.5, which helps in replication and inhibits the maturation of dendritic cells as a mechanism of avoiding elimination by the immune system. In addition, surface glycoproteins on the viral envelope promote the coating of herpes simplex virus with antibodies and complement factors, allowing the virus to appear as “self” and prevent immune system activation and elimination.

There are two herpes simplex virus types. While herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is generally associated with oral lesions like cold sores or fever blisters (see Viral Infections of the Skin and Eyes), herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2)is usually associated with genital herpes. However, both viruses can infect either location as well as other parts of the body. Oral-genital contact can spread either virus from the mouth to the genital region or vice versa.

Many infected individuals do not develop symptoms, and thus do not realize that they carry the virus. However, in some infected individuals, fever, chills, malaise, swollen lymph nodes, and pain precede the development of fluid-filled vesicles that may be irritating and uncomfortable. When these vesicles burst, they release infectious fluid and allow transmission of HSV. In addition, open herpes lesions can increase the risk of spreading or acquiring HIV.

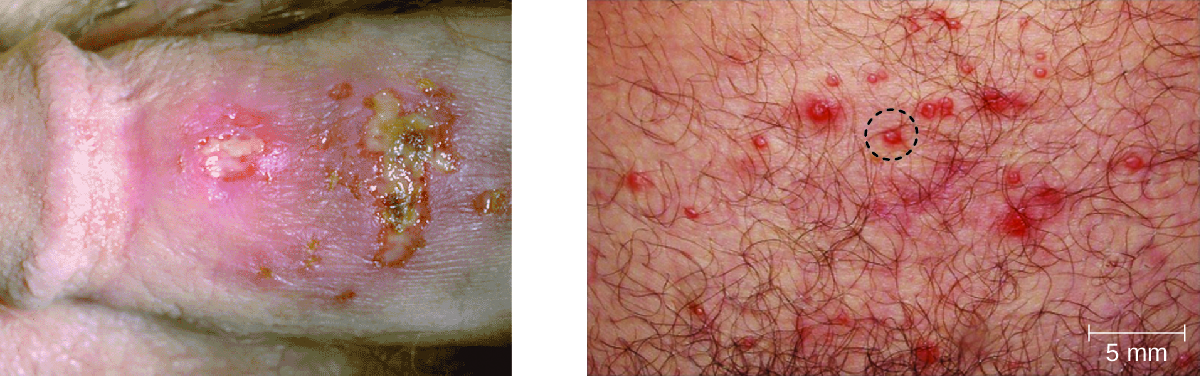

In men, the herpes lesions typically develop on the penis and may be accompanied by a watery discharge. In women, the vesicles develop most commonly on the vulva, but may also develop on the vagina or cervix (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The symptoms are typically mild, although the lesions may be irritating or accompanied by urinary discomfort. Use of condoms may not always be an effective means of preventing transmission of genital herpes since the lesions can occur on areas other than the genitals.

Herpes simplex viruses can cause recurrent infections because the virus can become latent and then be reactivated. This occurs more commonly with HSV-2 than with HSV-1.2 The virus moves down peripheral nerves, typically sensory neurons, to ganglia in the spine (either the trigeminal ganglion or the lumbar-sacral ganglia) and becomes latent. Reactivation can later occur, causing the formation of new vesicles. HSV-2 most effectively reactivates from the lumbar-sacral ganglia. Not everyone infected with HSV-2 experiences reactivations, which are typically associated with stressful conditions, and the frequency of reactivation varies throughout life and among individuals. Between outbreaks or when there are no obvious vesicles, the virus can still be transmitted.

Virologic and serologic techniques are used for diagnosis. The virus may be cultured from lesions. The immunostaining methods that are used to detect virus from cultures generally require less expertise than methods based on cytopathic effect (CPE), as well as being a less expensive option. However, PCR or other DNA amplification methods may be preferred because they provide the most rapid results without waiting for culture amplification. PCR is also best for detecting systemic infections. Serologic techniques are also useful in some circumstances, such as when symptoms persist but PCR testing is negative.

While there is no cure or vaccine for HSV-2 infections, antiviral medications are available that manage the infection by keeping the virus in its dormant or latent phase, reducing signs and symptoms. If the medication is discontinued, then the condition returns to its original severity. The recommended medications, which may be taken at the start of an outbreak or daily as a method of prophylaxis, are acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir.

Neonatal Herpes

Herpes infections in newborns, referred to as neonatal herpes, are generally transmitted from the mother to the neonate during childbirth, when the child is exposed to pathogens in the birth canal. Infections can occur regardless of whether lesions are present in the birth canal. In most cases, the infection of the newborn is limited to skin, mucous membranes, and eyes, and outcomes are good. However, sometimes the virus becomes disseminated and spreads to the central nervous system, resulting in motor function deficits or death.

In some cases, infections can occur before birth when the virus crosses the placenta. This can cause serious complications in fetal development and may result in spontaneous abortion or severe disabilities if the fetus survives. The condition is most serious when the mother is infected with HSV for the first time during pregnancy. Thus, expectant mothers are screened for HSV infection during the first trimester of pregnancy as part of the TORCH panel of prenatal tests (see How Pathogens Cause Disease). Systemic acyclovir treatment is recommended to treat newborns with neonatal herpes.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- Why are latent herpes virus infections still of clinical concern?

- How is neonatal herpes contracted?

Human Papillomas

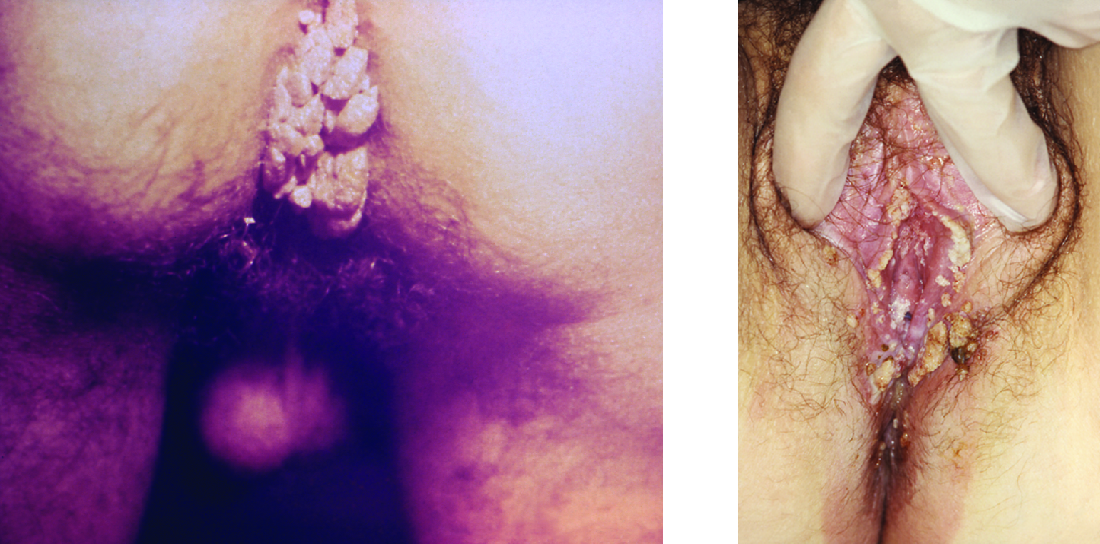

Warts of all types are caused by a variety of strains of human papillomavirus (HPV) (see Viral Infections of the Skin and Eyes). Condylomata acuminata, more commonly called genital warts or venereal warts (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), are an extremely prevalent STI caused by certain strains of HPV. Condylomata are irregular, soft, pink growths that are found on external genitalia or the anus.

HPV is a small, non-enveloped virus with a circular double-stranded DNA genome. Researchers have identified over 200 different strains (called types) of HPV, with approximately 40 causing STIs. While some types of HPV cause genital warts, HPV infection is often asymptomatic and self-limiting. However, genital HPV infection often co-occurs with other STIs like syphilis or gonorrhea. Additionally, some forms of HPV (not the same ones associated with genital warts) are associated with cervical cancers. At least 14 oncogenic (cancer-causing) HPV types are known to have a causal association with cervical cancers. Examples of oncogenic HPV are types 16 and 18, which are associated with 70% of cervical cancers.3 Oncogenic HPV types can also cause oropharyngeal cancer, anal cancer, vaginal cancer, vulvar cancer, and penile cancer. Most of these cancers are caused by HPV type 16. HPV virulence factors include proteins (E6 and E7) that are capable of inactivating tumor suppressor proteins, leading to uncontrolled cell division and the development of cancer.

HPV cannot be cultured, so molecular tests are the primary method used to detect HPV. While routine HPV screening is not recommended for men, it is included in guidelines for women. An initial screening for HPV at age 30, conducted at the same time as a Pap test, is recommended. If the tests are negative, then further HPV testing is recommended every five years. More frequent testing may be needed in some cases. The protocols used to collect, transport, and store samples vary based on both the type of HPV testing and the purpose of the testing. This should be determined in individual cases in consultation with the laboratory that will perform the testing.

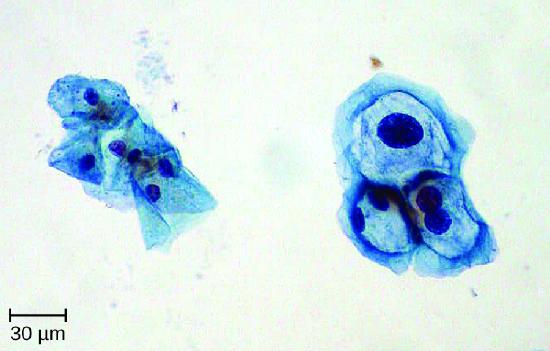

Because HPV testing is often conducted concurrently with Pap testing, the most common approach uses a single sample collection within one vial for both. This approach uses liquid-based cytology (LBC). The samples are then used for Pap smear cytology as well as HPV testing and genotyping. HPV can be recognized in Pap smears by the presence of cells called koilocytes (called koilocytosis or koilocytotic atypia). Koilocytes have a hyperchromatic atypical nucleus that stains darkly and a high ratio of nuclear material to cytoplasm. There is a distinct clear appearance around the nucleus called a perinuclear halo (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Most HPV infections resolve spontaneously; however, various therapies are used to treat and remove warts. Topical medications such as imiquimod (which stimulates the production of interferon), podofilox, or sinecatechins, may be effective. Warts can also be removed using cryotherapy or surgery, but these approaches are less effective for genital warts than for other types of warts. Electrocauterization and carbon dioxide laser therapy are also used for wart removal.

Regular Pap testing can detect abnormal cells that might progress to cervical cancer, followed by biopsy and appropriate treatment. Vaccines for some of the high risk HPV types are now available. Gardasil vaccine includes types 6, 11, 16 and 18 (types 6 and 11 are associated with 90% of genital wart infections and types 16 and 18 are associated with 70% of cervical cancers). Gardasil 9 vaccinates against the previous four types and an additional five high-risk types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58). Cervarix vaccine includes just HPV types 16 and 18. Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent infection with oncogenic HPV, but it is important to note that not all oncogenic HPV types are covered by the available vaccines. It is recommended for both boys and girls prior to sexual activity (usually between the ages of nine and fifteen).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

- What is diagnostic of an HPV infection in a Pap smear?

- What is the motivation for HPV vaccination?

Secret STIs

Few people who have an STI (or think they may have one) are eager to share that information publicly. In fact, many patients are even uncomfortable discussing the symptoms privately with their doctors. Unfortunately, the social stigma associated with STIs makes it harder for infected individuals to seek the treatment they need and creates the false perception that STIs are rare. In reality, STIs are quite common, but it is difficult to determine exactly how common.

A recent study on the effects of HPV vaccination found a baseline HPV prevalence of 26.8% for women between the ages of 14 and 59. Among women aged 20–24, the prevalence was 44.8%; in other words, almost half of the women in this age bracket had a current infection.4 According to the CDC, HSV-2 infection was estimated to have a prevalence of 15.5% in younger individuals (14–49 years of age) in 2007–2010, down from 20.3% in the same age group in 1988–1994. However, the CDC estimates that 87.4% of infected individuals in this age group have not been diagnosed by a physician.5

Another complicating factor is that many STIs can be asymptomatic or have long periods of latency. For example, the CDC estimates that among women ages 14–49 in the United States, about 2.3 million (3.1%) are infected with the sexually transmitted protozoan Trichomonas (see Protozoan Infections of the Urogenital System); however, in a study of infected women, 85% of those diagnosed with the infection were asymptomatic.6

Even when patients are treated for symptomatic STIs, it can be difficult to obtain accurate data on the number of cases. Whereas STIs like chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis are notifiable diseases—meaning each diagnosis must be reported by healthcare providers to the CDC—other STIs are not notifiable (e.g., genital herpes, genital warts, and trichomoniasis). Between the social taboos, the inconsistency of symptoms, and the lack of mandatory reporting, it can be difficult to estimate the true prevalence of STIs—but it is safe to say they are much more prevalent than most people think.

Viral Reproductive Tract Infections

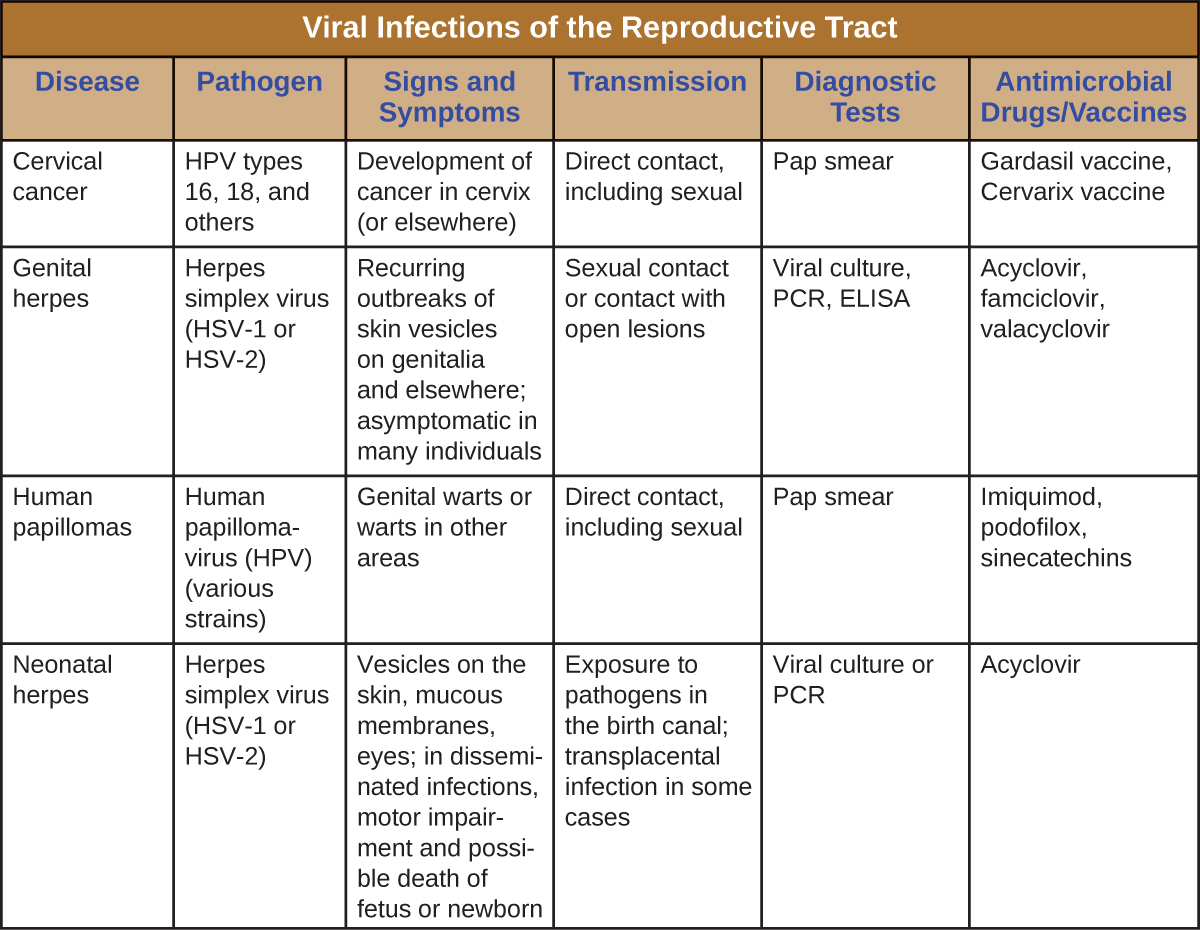

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) summarizes the most important features of viral diseases affecting the human reproductive tract.

Key Concepts and Summary

- Genital herpes is usually caused by HSV-2 (although HSV-1 can also be responsible) and may cause the development of infectious, potentially recurrent vesicles.

- Neonatal herpes can occur in babies born to infected mothers and can cause symptoms that range from relatively mild (more common) to severe.

- Human papillomaviruses are the most common sexually transmitted viruses and include strains that cause genital warts as well as strains that cause cervical cancer.

Footnotes

- 1 Catherine Lindsey Satterwhite, Elizabeth Torrone, Elissa Meites, Eileen F. Dunne, Reena Mahajan, M. Cheryl Bañez Ocfemia, John Su, Fujie Xu, and Hillard Weinstock. “Sexually Transmitted Infections Among US Women and Men: Prevalence and Incidence Estimates, 2008.” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 40, no. 3 (2013): 187–193.

- 2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “2015 Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment Guidelines: Genital Herpes,” 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/herpes.htm.

- 3 Lauren Thaxton and Alan G. Waxman. “Cervical Cancer Prevention: Immunization and Screening 2015.” Medical Clinics of North America 99, no. 3 (2015): 469–477.

- 4 Eileen F. Dunne, Elizabeth R. Unger, Maya Sternberg, Geraldine McQuillan, David C. Swan, Sonya S. Patel, and Lauri E. Markowitz. “Prevalence of HPV Infection Among Females in the United States.” Journal of the American Medical Association 297, no. 8 (2007): 813–819.

- 5 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Genital Herpes - CDC Fact Sheet,” 2015. www.cdc.gov/std/herpes/stdfac...s-detailed.htm.

- 6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Trichomoniasis Statistics,” 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/stats.htm.

Contributors and Attributions

Nina Parker, (Shenandoah University), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University), Anh-Hue Thi Tu (Georgia Southwestern State University), Philip Lister (Central New Mexico Community College), and Brian M. Forster (Saint Joseph’s University) with many contributing authors. Original content via Openstax (CC BY 4.0; Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction)