12.1: Normal Microbiota of the Body

- Page ID

- 31846

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast the microbiomes of various body sites

- Identify features of the body sites that might affect with microbes reside in each space

PART 1

Michael, a 10-year-old boy in generally good health, went to a birthday party on Sunday with his family. He ate many different foods but was the only one in the family to eat the undercooked hot dogs served by the hosts. Monday morning, he woke up feeling achy and nauseous, and he was running a fever of 38 °C (100.4 °F). His parents, assuming Michael had caught the flu, made him stay home from school and limited his activities. But after 4 days, Michael began to experience severe headaches, and his fever spiked to 40 °C (104 °F). Growing worried, his parents finally decide to take Michael to a nearby clinic.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- What signs and symptoms is Michael experiencing?

- What do these signs and symptoms tell us about the stage of Michael’s disease?

Normal Flora

Microbes are ubiquitous is a phrase that has been repeated often, but many people do not realize how close to home it is. Microbes not only live all around us, but also on our bodies- skin, nose, and gut. Many are living with us side-by-side in a mutualistic relationship that benefits everyone. In this section we explore those that live in harmony with us, at least temporarily.

Normal Microbiota of the Skin

The skin is home to a wide variety of normal microbiota, consisting of commensal organisms that derive nutrition from skin cells and secretions such as sweat and sebum. The normal microbiota of skin tends to inhibit transient-microbe colonization by producing antimicrobial substances and outcompeting other microbes that land on the surface of the skin. This helps to protect the skin from pathogenic infection.

The skin’s properties differ from one region of the body to another, as does the composition of the skin’s microbiota. The availability of nutrients and moisture partly dictates which microorganisms will thrive in a particular region of the skin. Relatively moist skin, such as that of the nares (nostrils) and underarms, has a much different microbiota than the dryer skin on the arms, legs, hands, and top of the feet. Some areas of the skin have higher densities of sebaceous glands. These sebum-rich areas, which include the back, the folds at the side of the nose, and the back of the neck, harbor distinct microbial communities that are less diverse than those found on other parts of the body.

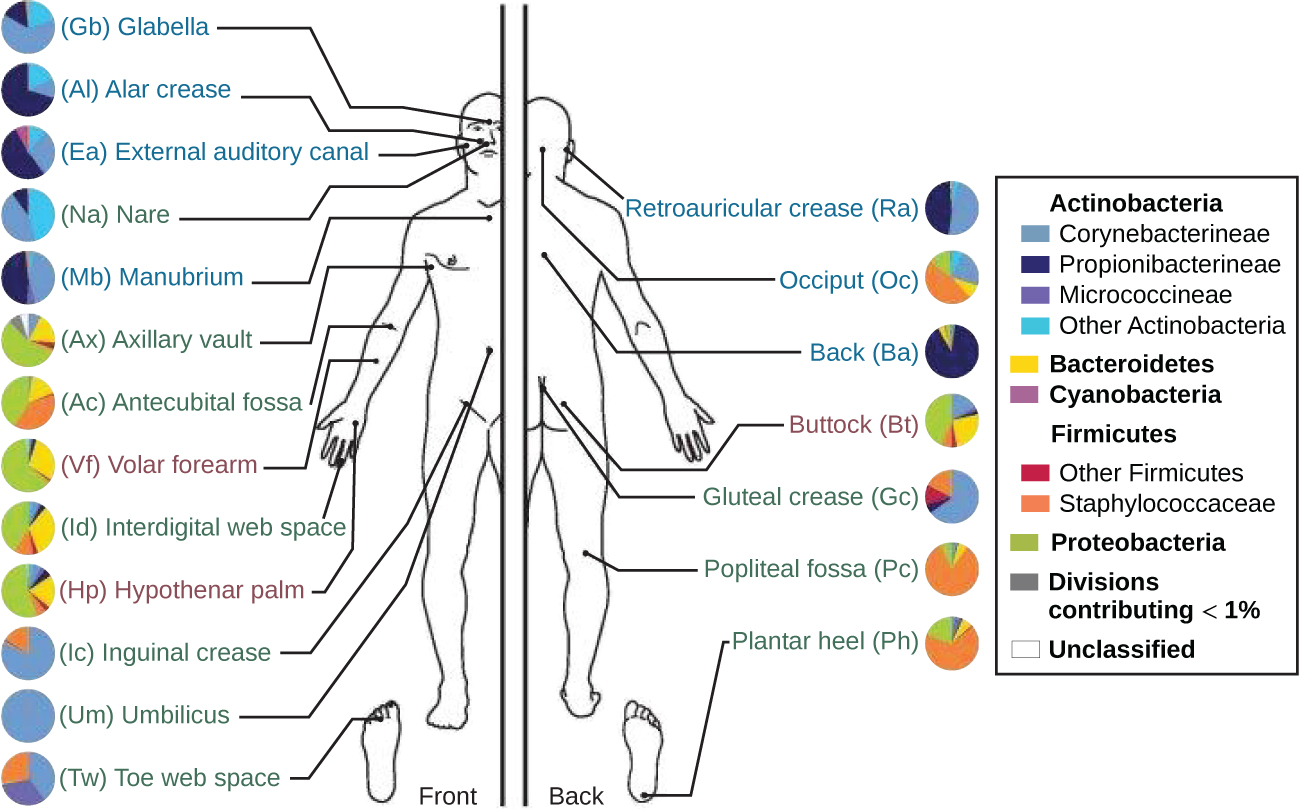

Different types of bacteria dominate the dry, moist, and sebum-rich regions of the skin. The most abundant microbes typically found in the dry and sebaceous regions are Betaproteobacteria and Propionibacteria, respectively. In the moist regions, Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus are most commonly found (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Viruses and fungi are also found on the skin, with Malassezia being the most common type of fungus found as part of the normal microbiota. The role and populations of viruses in the microbiota, known as viromes, are still not well understood, and there are limitations to the techniques used to identify them. However, Circoviridae, Papillomaviridae, and Polyomaviridaeappear to be the most common residents in the healthy skin virome.123

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

What are the four most common bacteria that are part of the normal skin microbiota?

Microbiota of the Eye

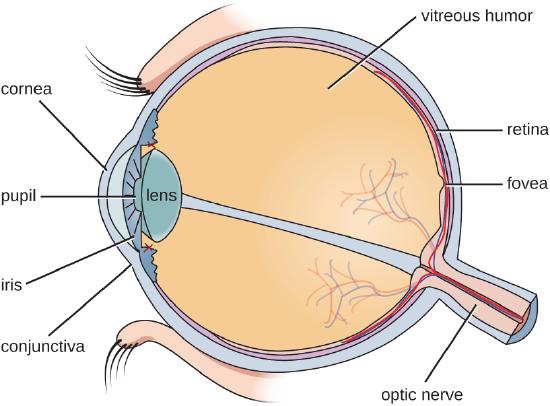

The surfaces of the eyeball and inner eyelid are mucous membranes called conjunctiva. The normal conjunctival microbiota has not been well characterized, but does exist. One small study (part of the Ocular Microbiome project) found twelve genera that were consistently present in the conjunctiva.4 These microbes are thought to help defend the membranes against pathogens. However, it is still unclear which microbes may be transient and which may form a stable microbiota.5

Use of contact lenses can cause changes in the normal microbiota of the conjunctiva by introducing another surface into the natural anatomy of the eye. Research is currently underway to better understand how contact lenses may impact the normal microbiota and contribute to eye disease. The watery material inside of the eyeball is called the vitreous humor. Unlike the conjunctiva, it is protected from contact with the environment and is almost always sterile, with no normal microbiota (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Mouth and GI tract

Microbes such as bacteria and archaea are abundant in the mouth and coat all of the surfaces of the oral cavity. The most well known genus is Streptococcus, but there are many others that have not been well characterized. Even within the mouth, different structures, such as the teeth or cheeks, host unique communities of both aerobic and anaerobic microbes. The number of microbes goes down and is essentially zero by the stomach. But after the stomach, microorganisms present in the small intestine can include lactobacilli, diptherioids and the fungus Candida. On the other hand, the large intestine (colon) contains a diverse and abundant microbiota that is important for normal function. These microbes include Bacteriodetes (especially the genera Bacteroides and Prevotella) and Firmicutes (especially members of the genus Clostridium). Methanogenic archaea and some fungi are also present, among many other species of bacteria. These microbes all aid in digestion and contribute to the production of feces, the waste excreted from the digestive tract, and flatus, the gas produced from microbial fermentation of undigested food. They can also produce valuable nutrients. For example, lactic acid bacteria such as bifidobacteria can synthesize vitamins, such as vitamin B12, folate, and riboflavin, that humans cannot synthesize themselves. E. coli found in the intestine can also break down food and help the body produce vitamin K, which is important for blood coagulation.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Microbes abound in the mouth down to the end of the esophagus. The stomach is generally not colonized, but the intestines have many microbes.

Normal Microbiota of the Respiratory System

The upper respiratory tract contains an abundant and diverse microbiota. The nasal passages and sinuses are primarily colonized by members of the Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. The most common bacteria identified include Staphylococcus epidermidis, viridans group streptococci (VGS), Corynebacterium spp. (diphtheroids), Propionibacterium spp., and Haemophilus spp. The oropharynx includes many of the same isolates as the nose and sinuses, with the addition of variable numbers of bacteria like species of Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Moraxella, and Eikenella, as well as some Candida fungal isolates. In addition, many healthy humans asymptomatically carry potential pathogens in the upper respiratory tract. As much as 20% of the population carry Staphylococcus aureus in their nostrils.6 The pharynx, too, can be colonized with pathogenic strains of Streptococcus, Haemophilus, and Neisseria.

The lower respiratory tract, by contrast, is scantily populated with microbes. Of the organisms identified in the lower respiratory tract, species of Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, and Veillonella are the most common. It is not clear at this time if these small populations of bacteria constitute a normal microbiota or if they are transients.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Microbes generally have a lot of mixing with the GI tract until the trachea. Microbes then decrease until the lungs, which should be sterile.

Normal Microbiota of the Urogenital System

Below the bladder, the normal microbiota of the male urogenital system is found primarily within the distal urethra and includes bacterial species that are commonly associated with the skin microbiota- think Staphylococcus. In women, the normal microbiota is found within the distal one third of the urethra and the vagina. The normal microbiota of the vagina becomes established shortly after birth and is a complex and dynamic population of bacteria that fluctuates in response to environmental changes. Members of the vaginal microbiota play an important role in the nonspecific defense against vaginal infections and sexually transmitted infections by occupying cellular binding sites and competing for nutrients. In addition, the production of lactic acid by members of the microbiota provides an acidic environment within the vagina that also serves as a defense against infections. For the majority of women, the lactic-acid–producing bacteria in the vagina are dominated by a variety of species of Lactobacillus. For women who lack sufficient lactobacilli in their vagina, lactic acid production comes primarily from other species of bacteria such as Leptotrichia spp., Megasphaera spp., and Atopobium vaginae. Lactobacillus spp. use glycogen from vaginal epithelial cells for metabolism and production of lactic acid. This process is tightly regulated by the hormone estrogen. Increased levels of estrogen correlate with increased levels of vaginal glycogen, increased production of lactic acid, and a lower vaginal pH. Therefore, decreases in estrogen during the menstrual cycle and with menopause are associated with decreased levels of vaginal glycogen and lactic acid, and a higher pH. In addition to producing lactic acid, Lactobacillus spp. also contribute to the defenses against infectious disease through their production of hydrogen peroxide and bacteriocins (antibacterial peptides).

Key Concepts and Summary

- Normal flora lives in a mutualistic relationship with humans. Humans benefit from microbes being there and microbes benefit too.

- What genera of microbes are represented in each area are highly diverse and dependent on defenses and resources are available in each area.

Footnotes

- 1 Belkaid, Y., and J.A. Segre. “Dialogue Between Skin Microbiota and Immunity,” Science 346 (2014) 6212:954–959.

- 2 Foulongne, Vincent, et al. “Human Skin Microbiota: High Diversity of DNA Viruses Identified on the Human Skin by High Throughput Sequencing.” PLoS ONE (2012) 7(6): e38499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038499.

- 3 Robinson, C.M., and J.K. Pfeiffer. “Viruses and the Microbiota.” Annual Review of Virology (2014) 1:55–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085550.

- 4 Abelson, M.B., Lane, K., and Slocum, C.. “The Secrets of Ocular Microbiomes.” Review of Ophthalmology June 8, 2015. www.reviewofophthalmology.com...isease/c/55178. Accessed Sept 14, 2016.

- 5 Shaikh-Lesko, R. “Visualizing the Ocular Microbiome.” The Scientist May 12, 2014. http://www.the-scientist.com/?articl...lar-Microbiome. Accessed Sept 14, 2016.

- 6 J. Kluytmans et al. “Nasal Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology, Underlying Mechanisms, and Associated Risks.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 10 no. 3 (1997):505–520.

Contributor

Nina Parker, (Shenandoah University), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University), Anh-Hue Thi Tu (Georgia Southwestern State University), Philip Lister (Central New Mexico Community College), and Brian M. Forster (Saint Joseph’s University) with many contributing authors. Original content via Openstax (CC BY 4.0; Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction)