7.8: Groups of Protists

- Page ID

- 46153

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Differentiate between groups of protists

In the span of several decades, the Kingdom Protista has been disassembled because sequence analyses have revealed new genetic (and therefore evolutionary) relationships among these eukaryotes. Moreover, protists that exhibit similar morphological features may have evolved analogous structures because of similar selective pressures—rather than because of recent common ancestry. This phenomenon, called convergent evolution, is one reason why protist classification is so challenging. The emerging classification scheme groups the entire domain Eukaryota into six “supergroups” that contain all of the protists as well as animals, plants, and fungi that evolved from a common ancestor (Figure 1). The supergroups are believed to be monophyletic, meaning that all organisms within each supergroup are believed to have evolved from a single common ancestor, and thus all members are most closely related to each other than to organisms outside that group. There is still evidence lacking for the monophyly of some groups.

The classification of eukaryotes is still in flux, and the six supergroups may be modified or replaced by a more appropriate hierarchy as genetic, morphological, and ecological data accumulate. Keep in mind that the classification scheme presented here is just one of several hypotheses, and the true evolutionary relationships are still to be determined. When learning about protists, it is helpful to focus less on the nomenclature and more on the commonalities and differences that define the groups themselves.

Excavata

Many of the protist species classified into the supergroup Excavata are asymmetrical, single-celled organisms with a feeding groove “excavated” from one side. This supergroup includes heterotrophic predators, photosynthetic species, and parasites. Its subgroups are the diplomonads, parabasalids, and euglenozoans.

Diplomonads

Among the Excavata are the diplomonads, which include the intestinal parasite, Giardia lamblia (Figure 2). Until recently, these protists were believed to lack mitochondria. Mitochondrial remnant organelles, called mitosomes, have since been identified in diplomonads, but these mitosomes are essentially nonfunctional. Diplomonads exist in anaerobic environments and use alternative pathways, such as glycolysis, to generate energy. Each diplomonad cell has two identical nuclei and uses several flagella for locomotion.

Parabasalids

A second Excavata subgroup, the parabasalids, also exhibits semi-functional mitochondria. In parabasalids, these structures function anaerobically and are called hydrogenosomes because they produce hydrogen gas as a byproduct. Parabasalids move with flagella and membrane rippling. Trichomonas vaginalis, a parabasalid that causes a sexually transmitted disease in humans, employs these mechanisms to transit through the male and female urogenital tracts. T. vaginalis causes trichamoniasis, which appears in an estimated 180 million cases worldwide each year. Whereas men rarely exhibit symptoms during an infection with this protist, infected women may become more susceptible to secondary infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and may be more likely to develop cervical cancer. Pregnant women infected with T. vaginalis are at an increased risk of serious complications, such as pre-term delivery.

Euglenozoans

Euglenozoans includes parasites, heterotrophs, autotrophs, and mixotrophs, ranging in size from 10 to 500 µm. Euglenoids move through their aquatic habitats using two long flagella that guide them toward light sources sensed by a primitive ocular organ called an eyespot. The familiar genus, Euglena, encompasses some mixotrophic species that display a photosynthetic capability only when light is present. In the dark, the chloroplasts of Euglena shrink up and temporarily cease functioning, and the cells instead take up organic nutrients from their environment.

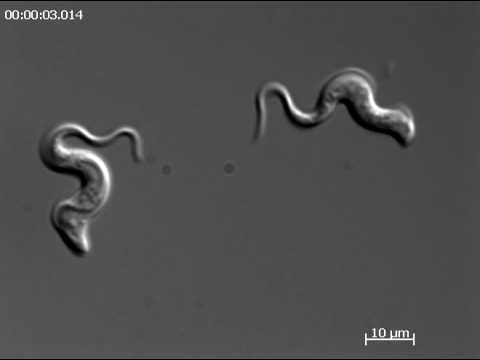

The human parasite, Trypanosoma brucei, belongs to a different subgroup of Euglenozoa, the kinetoplastids. The kinetoplastid subgroup is named after the kinetoplast, a DNA mass carried within the single, oversized mitochondrion possessed by each of these cells. This subgroup includes several parasites, collectively called trypanosomes, which cause devastating human diseases and infect an insect species during a portion of their life cycle. T. brucei develops in the gut of the tsetse fly after the fly bites an infected human or other mammalian host. The parasite then travels to the insect salivary glands to be transmitted to another human or other mammal when the infected tsetse fly consumes another blood meal. T. brucei is common in central Africa and is the causative agent of African sleeping sickness, a disease associated with severe chronic fatigue, coma, and can be fatal if left untreated.

Watch this video to see T. brucei swimming. Note that there is no audio in this video.

Chromalveolata

Current evidence suggests that species classified as chromalveolates are derived from a common ancestor that engulfed a photosynthetic red algal cell, which itself had already evolved chloroplasts from an endosymbiotic relationship with a photosynthetic prokaryote. Therefore, the ancestor of chromalveolates is believed to have resulted from a secondary endosymbiotic event. However, some chromalveolates appear to have lost red alga-derived plastid organelles or lack plastid genes altogether. Therefore, this supergroup should be considered a hypothesis-based working group that is subject to change. Chromalveolates include very important photosynthetic organisms, such as diatoms, brown algae, and significant disease agents in animals and plants. The chromalveolates can be subdivided into alveolates and stramenopiles.

Alveolates: Dinoflagellates, Apicomplexians, and Ciliates

A large body of data supports that the alveolates are derived from a shared common ancestor. The alveolates are named for the presence of an alveolus, or membrane-enclosed sac, beneath the cell membrane. The exact function of the alveolus is unknown, but it may be involved in osmoregulation. The alveolates are further categorized into some of the better-known protists: the dinoflagellates, the apicomplexans, and the ciliates.

Dinoflagellates exhibit extensive morphological diversity and can be photosynthetic, heterotrophic, or mixotrophic. Many dinoflagellates are encased in interlocking plates of cellulose. Two perpendicular flagella fit into the grooves between the cellulose plates, with one flagellum extending longitudinally and a second encircling the dinoflagellate (Figure 4). Together, the flagella contribute to the characteristic spinning motion of dinoflagellates. These protists exist in freshwater and marine habitats, and are a component of plankton, the typically microscopic organisms that drift through the water and serve as a crucial food source for larger aquatic organisms.

Some dinoflagellates generate light, called bioluminescence, when they are jarred or stressed. Large numbers of marine dinoflagellates (billions or trillions of cells per wave) can emit light and cause an entire breaking wave to twinkle or take on a brilliant blue color (Figure 5). For approximately 20 species of marine dinoflagellates, population explosions (also called blooms) during the summer months can tint the ocean with a muddy red color. This phenomenon is called a red tide, and it results from the abundant red pigments present in dinoflagellate plastids. In large quantities, these dinoflagellate species secrete an asphyxiating toxin that can kill fish, birds, and marine mammals. Red tides can be massively detrimental to commercial fisheries, and humans who consume these protists may become poisoned.

The apicomplexan protists are so named because their microtubules, fibrin, and vacuoles are asymmetrically distributed at one end of the cell in a structure called an apical complex (Figure 6). The apical complex is specialized for entry and infection of host cells. Indeed, all apicomplexans are parasitic. This group includes the genus Plasmodium, which causes malaria in humans. Apicomplexan life cycles are complex, involving multiple hosts and stages of sexual and asexual reproduction.

The ciliates, which include Paramecium and Tetrahymena, are a group of protists 10 to 3,000 micrometers in length that are covered in rows, tufts, or spirals of tiny cilia. By beating their cilia synchronously or in waves, ciliates can coordinate directed movements and ingest food particles. Certain ciliates have fused cilia-based structures that function like paddles, funnels, or fins. Ciliates also are surrounded by a pellicle, providing protection without compromising agility. The genus Paramecium includes protists that have organized their cilia into a plate-like primitive mouth, called an oral groove, which is used to capture and digest bacteria (Figure 7). Food captured in the oral groove enters a food vacuole, where it combines with digestive enzymes. Waste particles are expelled by an exocytic vesicle that fuses at a specific region on the cell membrane, called the anal pore. In addition to a vacuole-based digestive system, Paramecium also uses contractile vacuoles, which are osmoregulatory vesicles that fill with water as it enters the cell by osmosis and then contract to squeeze water from the cell.

Watch the video of the contractile vacuole of Paramecium expelling water to keep the cell osmotically balanced.

Paramecium has two nuclei, a macronucleus and a micronucleus, in each cell. The micronucleus is essential for sexual reproduction, whereas the macronucleus directs asexual binary fission and all other biological functions. The process of sexual reproduction in Paramecium underscores the importance of the micronucleus to these protists. Paramecium and most other ciliates reproduce sexually by conjugation. This process begins when two different mating types of Paramecium make physical contact and join with a cytoplasmic bridge (Figure 8). The diploid micronucleus in each cell then undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid micronuclei. Three of these degenerate in each cell, leaving one micronucleus that then undergoes mitosis, generating two haploid micronuclei. The cells each exchange one of these haploid nuclei and move away from each other. A similar process occurs in bacteria that have plasmids. Fusion of the haploid micronuclei generates a completely novel diploid pre-micronucleus in each conjugative cell. This pre-micronucleus undergoes three rounds of mitosis to produce eight copies, and the original macronucleus disintegrates. Four of the eight pre-micronuclei become full-fledged micronuclei, whereas the other four perform multiple rounds of DNA replication and go on to become new macronuclei. Two cell divisions then yield four new Paramecia from each original conjugative cell.

Which of the following statements about Paramecium sexual reproduction is false?

- The macronuclei are derived from micronuclei.

- Both mitosis and meiosis occur during sexual reproduction.

- The conjugate pair swaps macronucleii.

- Each parent produces four daughter cells.

[reveal-answer q=”294017″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a=”294017″]Statement c is false.[/hidden-answer]

Stramenopiles: Diatoms, Brown Algae, Golden Algae and Oomycetes

The other subgroup of chromalveolates, the stramenopiles, includes photosynthetic marine algae and heterotrophic protists. The unifying feature of this group is the presence of a textured, or “hairy,” flagellum. Many stramenopiles also have an additional flagellum that lacks hair-like projections (Figure 9). Members of this subgroup range in size from single-celled diatoms to the massive and multicellular kelp.

The diatoms are unicellular photosynthetic protists that encase themselves in intricately patterned, glassy cell walls composed of silicon dioxide in a matrix of organic particles (Figure 10). These protists are a component of freshwater and marine plankton. Most species of diatoms reproduce asexually, although some instances of sexual reproduction and sporulation also exist. Some diatoms exhibit a slit in their silica shell, called a raphe. By expelling a stream of mucopolysaccharides from the raphe, the diatom can attach to surfaces or propel itself in one direction.

During periods of nutrient availability, diatom populations bloom to numbers greater than can be consumed by aquatic organisms. The excess diatoms die and sink to the sea floor where they are not easily reached by saprobes that feed on dead organisms. As a result, the carbon dioxide that the diatoms had consumed and incorporated into their cells during photosynthesis is not returned to the atmosphere. In general, this process by which carbon is transported deep into the ocean is described as the biological carbon pump, because carbon is “pumped” to the ocean depths where it is inaccessible to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. The biological carbon pump is a crucial component of the carbon cycle that maintains lower atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

Like diatoms, golden algae are largely unicellular, although some species can form large colonies. Their characteristic gold color results from their extensive use of carotenoids, a group of photosynthetic pigments that are generally yellow or orange in color. Golden algae are found in both freshwater and marine environments, where they form a major part of the plankton community.

The brown algae are primarily marine, multicellular organisms that are known colloquially as seaweeds. Giant kelps are a type of brown algae. Some brown algae have evolved specialized tissues that resemble terrestrial plants, with root-like holdfasts, stem-like stipes, and leaf-like blades that are capable of photosynthesis. The stipes of giant kelps are enormous, extending in some cases for 60 meters. A variety of algal life cycles exists, but the most complex is alternation of generations, in which both haploid and diploid stages involve multicellularity. Compare this life cycle to that of humans, for instance. Haploid gametes produced by meiosis (sperm and egg) combine in fertilization to generate a diploid zygote that undergoes many rounds of mitosis to produce a multicellular embryo and then a fetus. However, the individual sperm and egg themselves never become multicellular beings. Terrestrial plants also have evolved alternation of generations. In the brown algae genus Laminaria, haploid spores develop into multicellular gametophytes, which produce haploid gametes that combine to produce diploid organisms that then become multicellular organisms with a different structure from the haploid form (Figure 11). Certain other organisms perform alternation of generations in which both the haploid and diploid forms look the same.

Which of the following statements about the Laminaria life cycle is false?

- 1n zoospores form in the sporangia.

- The sporophyte is the 2n plant.

- The gametophyte is diploid.

- Both the gametophyte and sporophyte stages are multicellular.

[reveal-answer q=”65382″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a=”65382″]Statement c is false.[/hidden-answer]

The water molds, oomycetes (“egg fungus”), were so-named based on their fungus-like morphology, but molecular data have shown that the water molds are not closely related to fungi. The oomycetes are characterized by a cellulose-based cell wall and an extensive network of filaments that allow for nutrient uptake. As diploid spores, many oomycetes have two oppositely directed flagella (one hairy and one smooth) for locomotion. The oomycetes are nonphotosynthetic and include many saprobes and parasites. The saprobes appear as white fluffy growths on dead organisms (Figure 12).

Most oomycetes are aquatic, but some parasitize terrestrial plants. One plant pathogen is Phytophthora infestans, the causative agent of late blight of potatoes, such as occurred in the nineteenth century Irish potato famine.

Rhizaria

The Rhizaria supergroup includes many of the amoebas, most of which have threadlike or needle-like pseudopodia (Ammoniatepida, a Rhizaria species, can be seen in Figure 13).

Pseudopodia function to trap and engulf food particles and to direct movement in rhizarian protists. These pseudopods project outward from anywhere on the cell surface and can anchor to a substrate. The protist then transports its cytoplasm into the pseudopod, thereby moving the entire cell. This type of motion, called cytoplasmic streaming, is used by several diverse groups of protists as a means of locomotion or as a method to distribute nutrients and oxygen.

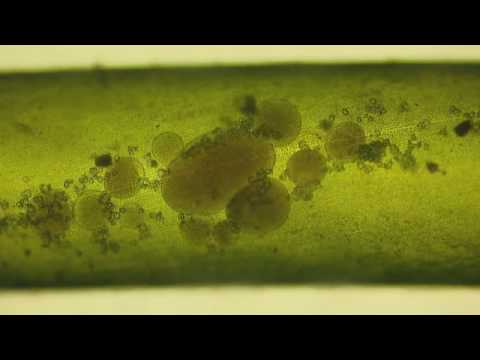

Take a look at this video to see cytoplasmic streaming in a green alga. Note that there is no audio in this video.

Forams

Foraminiferans, or forams, are unicellular heterotrophic protists, ranging from approximately 20 micrometers to several centimeters in length, and occasionally resembling tiny snails (Figure 14).

As a group, the forams exhibit porous shells, called tests that are built from various organic materials and typically hardened with calcium carbonate. The tests may house photosynthetic algae, which the forams can harvest for nutrition. Foram pseudopodia extend through the pores and allow the forams to move, feed, and gather additional building materials. Typically, forams are associated with sand or other particles in marine or freshwater habitats. Foraminiferans are also useful as indicators of pollution and changes in global weather patterns.

Radiolarians

A second subtype of Rhizaria, the radiolarians, exhibit intricate exteriors of glassy silica with radial or bilateral symmetry (Figure 15). Needle-like pseudopods supported by microtubules radiate outward from the cell bodies of these protists and function to catch food particles. The shells of dead radiolarians sink to the ocean floor, where they may accumulate in 100 meter-thick depths. Preserved, sedimented radiolarians are very common in the fossil record.

Archaeplastida

Red algae and green algae are included in the supergroup Archaeplastida. It was from a common ancestor of these protists that the land plants evolved, since their closest relatives are found in this group. Molecular evidence supports that all Archaeplastida are descendents of an endosymbiotic relationship between a heterotrophic protist and a cyanobacterium. The red and green algae include unicellular, multicellular, and colonial forms.

Red Algae

Red algae, or rhodophytes, are primarily multicellular, lack flagella, and range in size from microscopic, unicellular protists to large, multicellular forms grouped into the informal seaweed category. The red algae life cycle is an alternation of generations. Some species of red algae contain phycoerythrins, photosynthetic accessory pigments that are red in color and outcompete the green tint of chlorophyll, making these species appear as varying shades of red. Other protists classified as red algae lack phycoerythrins and are parasites. Red algae are common in tropical waters where they have been detected at depths of 260 meters. Other red algae exist in terrestrial or freshwater environments.

Green Algae: Chlorophytes and Charophytes

The most abundant group of algae is the green algae. The green algae exhibit similar features to the land plants, particularly in terms of chloroplast structure. That this group of protists shared a relatively recent common ancestor with land plants is well supported. The green algae are subdivided into the chlorophytes and the charophytes. The charophytes are the closest living relatives to land plants and resemble them in morphology and reproductive strategies. Charophytes are common in wet habitats, and their presence often signals a healthy ecosystem.

The chlorophytes exhibit great diversity of form and function. Chlorophytes primarily inhabit freshwater and damp soil, and are a common component of plankton. Chlamydomonas is a simple, unicellular chlorophyte with a pear-shaped morphology and two opposing, anterior flagella that guide this protist toward light sensed by its eyespot. More complex chlorophyte species exhibit haploid gametes and spores that resemble Chlamydomonas.

The chlorophyte Volvox is one of only a few examples of a colonial organism, which behaves in some ways like a collection of individual cells, but in other ways like the specialized cells of a multicellular organism (Figure 16). Volvox colonies contain 500 to 60,000 cells, each with two flagella, contained within a hollow, spherical matrix composed of a gelatinous glycoprotein secretion. Individual Volvox cells move in a coordinated fashion and are interconnected by cytoplasmic bridges. Only a few of the cells reproduce to create daughter colonies, an example of basic cell specialization in this organism.

True multicellular organisms, such as the sea lettuce, Ulva, are represented among the chlorophytes. In addition, some chlorophytes exist as large, multinucleate, single cells. Species in the genus Caulerpa exhibit flattened fern-like foliage and can reach lengths of 3 meters (Figure 17). Caulerpa species undergo nuclear division, but their cells do not complete cytokinesis, remaining instead as massive and elaborate single cells.

Amoebozoa

The amoebozoans characteristically exhibit pseudopodia that extend like tubes or flat lobes, rather than the hair-like pseudopodia of rhizarian amoeba (Figure 18). The Amoebozoa include several groups of unicellular amoeba-like organisms that are free-living or parasites.

Slime Molds

A subset of the amoebozoans, the slime molds, has several morphological similarities to fungi that are thought to be the result of convergent evolution. For instance, during times of stress, some slime molds develop into spore-generating fruiting bodies, much like fungi.

The slime molds are categorized on the basis of their life cycles into plasmodial or cellular types. Plasmodial slime molds are composed of large, multinucleate cells and move along surfaces like an amorphous blob of slime during their feeding stage (Figure 19). Food particles are lifted and engulfed into the slime mold as it glides along. Upon maturation, the plasmodium takes on a net-like appearance with the ability to form fruiting bodies, or sporangia, during times of stress. Haploid spores are produced by meiosis within the sporangia, and spores can be disseminated through the air or water to potentially land in more favorable environments. If this occurs, the spores germinate to form ameboid or flagellate haploid cells that can combine with each other and produce a diploid zygotic slime mold to complete the life cycle.

The cellular slime molds function as independent amoeboid cells when nutrients are abundant (Figure 20). When food is depleted, cellular slime molds pile onto each other into a mass of cells that behaves as a single unit, called a slug. Some cells in the slug contribute to a 2–3-millimeter stalk, drying up and dying in the process. Cells atop the stalk form an asexual fruiting body that contains haploid spores. As with plasmodial slime molds, the spores are disseminated and can germinate if they land in a moist environment. One representative genus of the cellular slime molds is Dictyostelium, which commonly exists in the damp soil of forests.

Watch this video to see the formation of a fruiting body by a cellular slime mold. Note that there isn’t any narration in the video.

Opisthokonta

The opisthokonts include the animal-like choanoflagellates, which are believed to resemble the common ancestor of sponges and, in fact, all animals.

Choanoflagellates include unicellular and colonial forms, and number about 244 described species. These organisms exhibit a single, apical flagellum that is surrounded by a contractile collar composed of microvilli. The collar uses a similar mechanism to sponges to filter out bacteria for ingestion by the protist. The morphology of choanoflagellates was recognized early on as resembling the collar cells of sponges, and suggesting a possible relationship to animals. The Mesomycetozoa form a small group of parasites, primarily of fish, and at least one form that can parasitize humans. Their life cycles are poorly understood.

These organisms are of special interest, because they appear to be so closely related to animals. In the past, they were grouped with fungi and other protists based on their morphology. Some phylogenetic trees still group animals and fungi into the Opisthokonta supergroup though this is also considered a protist specific group in other phylogenies.

Contributors and Attributions

- Introduction to Groups of Protists. Authored by: Shelli Carter and Lumen Learning. Provided by: Lumen Learning. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Biology. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72...f21b5eabd@10.8

- Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream form. Authored by: TheOtonII. Located at: https://youtu.be/EnsydwITLYk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Paramecium and Osmosis. Authored by: ppornelubio. Located at: https://youtu.be/iG6Dd3COug4. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- John Bonner's slime mold movies. Authored by: Princeton University. Located at: https://youtu.be/bkVhLJLG7ug. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

- Sphaeroeca colony. Authored by: Dhzanette. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sphaeroeca-colony.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright