14.4: Functions of the Male Reproductive System

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 30721

Colorful Sperm

The false-color image in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows real human sperm. The tiny gametes are obviously greatly magnified in the picture because they are actually the smallest of all human cells. In fact, human sperm cells are small, even when compared with sperm cells of other animals. Mice sperm are about twice the length of human sperm! Human sperm may be small in size, but in a normal, healthy man, huge numbers of them are usually released during each ejaculation. There may be hundreds of millions of sperm cells in a single teaspoon of semen. Producing sperm is one of the major functions of the male reproductive system.

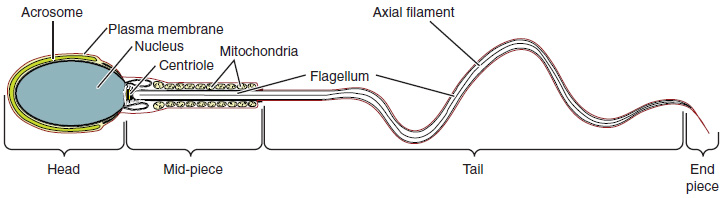

Sperm Anatomy

A mature sperm cell has several structures that help it reach and penetrate an egg. These are labeled in the drawing of a sperm shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

- The head is the part of the sperm that contains the nucleus — and not much else. The nucleus, in turn, contains tightly coiled DNA that is the male parent’s contribution to the genetic makeup of a zygote (if one forms). Each sperm is a haploid cell, containing half the chromosomal complement of a normal, diploid body cell.

- The front of the head is an area called the acrosome. The acrosome contains enzymes that help the sperm penetrate an egg (if it reaches one).

- The midpiece is the part of the sperm between the head and the flagellum tail. The midpiece is packed with mitochondria that produce the energy needed to move the flagellum.

- The flagellum (also called the tail) can rotate like a propeller, allowing the sperm to “swim” through the female reproductive tract to reach an egg if one is present.

Spermatogenesis

The process of producing sperm is known as spermatogenesis. Spermatogenesis normally starts when a boy reaches puberty, and it usually continues uninterrupted until death, although a decrease in sperm production generally occurs at older ages. A young, healthy male may produce hundreds of millions of sperm a day! Only about half of these, however, are likely to become viable, mature sperm.

Where Sperm Are Produced

Spermatogenesis occurs in the seminiferous tubules in the testes. Spermatogenesis requires high concentrations of testosterone. Testosterone is secreted by Leydig cells, which are adjacent to the seminiferous tubules in the testes.

Sperm production in the seminiferous tubules is very sensitive to temperature. This may be the most important reason the testes are located outside the body in the scrotum. The temperature inside the scrotum is generally about 2 degrees Celsius (almost 4 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than core body temperature. This lower temperature is optimal for spermatogenesis. The scrotum regulates its internal temperature as needed by contractions of the smooth muscles lining the scrotum. When the temperature inside the scrotum becomes too low, the scrotal muscles contract. The contraction of the muscles pulls the scrotum higher against the body, where the temperature is warmer. The opposite occurs when the temperature inside the scrotum becomes too high.

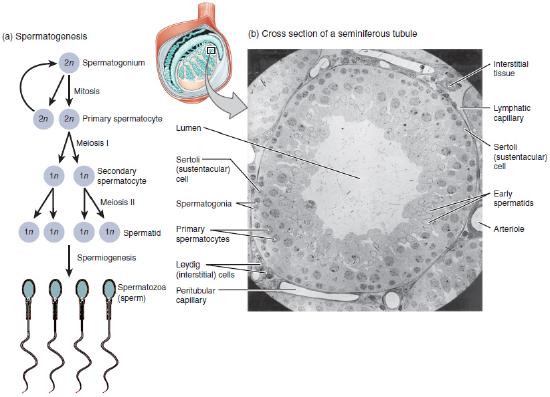

Events of Spermatogenesis

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) summarizes of the main cellular events that occur in the process of spermatogenesis. The process begins with a diploid stem cell called a spermatogonium (plural, spermatogonia), and involves several cell divisions. The entire process takes at least ten weeks to complete, including maturation in the epididymis.

- A spermatogonium undergoes mitosis to produce two diploid cells called primary spermatocytes. One of the primary spermatocytes goes on to produce sperm. The other replenishes the reserve of spermatogonia.

- The primary spermatocyte undergoes meiosis I to produce two haploid daughter cells called secondary spermatocytes.

- The secondary spermatocytes rapidly undergo meiosis II to produce a total of four haploid daughter cells called spermatids.

- The spermatids begin to form a tail, and their DNA becomes highly condensed. Unnecessary cytoplasm and organelles are removed from the cells, and they form a head, midpiece, and flagellum. The resulting cells are sperm (spermatozoa).

As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), the events of spermatogenesis begin near the wall of the seminiferous tubule — where spermatogonia are located — and continue inward toward the lumen of the tubule. Sertoli cells extend from the wall of the seminiferous tubule inward toward the lumen, so they are in contact with developing sperm at all stages of spermatogenesis. Sertoli cells play several roles in spermatogenesis:

- They secrete endocrine hormones that help regulate spermatogenesis.

- They secrete substances that initiate meiosis.

- They concentrate testosterone (from Leydig cells), which is needed at high levels to maintain spermatogenesis.

- They phagocytize the extra cytoplasm that is shed from developing sperm cells.

- They secrete a testicular fluid that helps carry sperm into the epididymis.

- They maintain a blood-testis barrier, so immune system cells cannot reach and attack the sperm

Maturation in the Epididymis

Although the sperm produced in the testes have tails, they are not yet motile (able to “swim”). The non-motile sperms are transported to the epididymis in the testicular fluid that is secreted by Sertoli cells with the help of peristaltic contractions. In the epididymis, the sperms gain motility, so they are capable of swimming up the female genital tract and reaching an egg. The mature sperms are stored in the epididymis until ejaculation occurs.

Ejaculation

Sperms are released from the body during ejaculation, which typically occurs during orgasm. Hundreds of millions of mature sperm — contained within a small amount of thick, whitish fluid called semen — are propelled from the penis during a normal ejaculation.

How Ejaculation Occurs

Ejaculation occurs when peristalsis of the muscle layers of the vas deferens and other accessory structures propel sperm from the epididymes, where mature sperm are stored. The muscle contractions force the sperm through the vas deferens and the ejaculatory ducts, and then out of the penis through the urethra. Due to the peristaltic action of the muscles, the ejaculation occurs in a series of spurts.

The Role of Semen

As sperms travel through the ejaculatory ducts during ejaculation, they mix with secretions from the seminal vesicles, prostate gland, and bulbourethral glands to form semen (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The average amount of semen per ejaculate is about 3.7 mL, which is a little less than a teaspoonful. Most of this volume of semen consists of glandular secretions, with the hundreds of millions of sperm cells actually contributing relatively little to the total volume.

The secretions in semen are important for the survival and motility of sperm. They provide a medium through which sperm can swim. They also include sperm-sustaining substances, such as high concentrations of the sugar fructose, which is the main source of energy for sperm. In addition, semen contains many alkaline substances that help neutralize the acidic environment in the female vagina. This protects the DNA in sperm from being denatured by the acid and prolongs the life of sperm in the female reproductive tract.

Erection

Besides providing a way for sperm to leave the body, the main role of the penis in reproduction is intromission or depositing sperm in the vagina of the female reproductive tract. Intromission depends on the ability of the penis to become stiff and erect, a state referred to as an erection. The human penis, unlike that of most other mammals, contains no erectile bone. Instead, in order to reach its erect state, it relies entirely on engorgement with the blood of its columns of spongy tissue. During sexual arousal, the arteries that supply blood to the penis dilate, allowing more blood to fill the spongy tissue. The now-engorged spongy tissue presses against and constricts the veins that carry blood away from the penis. As a result, more blood enters than leaves the penis, until a constant erectile size is achieved.

In addition to sperm, the penis also transports urine out of the body. These two functions cannot occur simultaneously. During an erection, the sphincters that prevent urine from leaving the bladder are controlled by centers in the brain so they cannot relax and allow urine to enter the urethra.

Testosterone Production

The final major function of the male reproductive system is the production of the male sex hormone testosterone. In mature males, this occurs mainly in the testes. Testosterone production is under the control of luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland. LH stimulates Leydig cells in the testes to secrete testosterone.

Testosterone is important for male sexual development at puberty. It stimulates maturation of the male reproductive organs, as well as the development of secondary male sex characteristics (such as facial hair). Testosterone is also needed in mature males for normal spermatogenesis to be maintained in the testes. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary gland is also needed for spermatogenesis to occur, in part because it helps Sertoli cells in the testes concentrate testosterone to high enough levels to maintain sperm production. Testosterone is also needed for the proper functioning of the prostate gland. In addition, testosterone plays a role in erection, allowing sperm to be deposited within the female reproductive tract.

Feature: My Human Body

If you’re a man and you use a laptop computer on your lap for long periods of time, you may be decreasing your fertility. The reason? A laptop computer generates considerable heat, and its proximity to the scrotum during typical use results in a significant rise in temperature inside the scrotum. Spermatogenesis is very sensitive to high temperatures, so it may be adversely affected by laptop computer use. If you want to avoid the potentially fertility-depressing effect of laptop computer use, you might want to consider using your laptop computer on a table or other surface rather than on your lap — at least when you log on for long computer sessions. Other activities that raise scrotal temperature and have the potential to reduce spermatogenesis including soaking in hot tubs, wearing tight clothing, and biking. Although the effects of short-term scrotal heating on fertility seem to be temporary, years of such heat exposure may cause irreversible effects on sperm production.

Review

- List parts of mature sperm.

- What is spermatogenesis? When does it occur?

- Where does spermatogenesis take place? State one role of Sertoli cells in spermatogenesis.

- Summarize the steps of sperm production, naming the cells and processes involved.

- What must happen to sperm before they are able to “swim”?

- What is ejaculation?

- Describe semen and its components.

- Define intromission. How is it related to erection?

- Explain how an erection occurs.

- What cells secrete testosterone? What controls this process?

- Identify the functions of testosterone in males.

- Which of the following cells are haploid? Choose all that apply.

- spermatids

- spermatogonia

- primary spermatocytes

- secondary spermatocytes

- mature sperm

- Describe one way in which Leydig and Sertoli cells work together to maintain spermatogenesis.

- True or False: When it is cold outside the body, the scrotal muscles relax.

- True or False: During an erection, the arteries and veins of the penis dilate.

Explore More

How do queer couples have babies? Learn more here:

Watch this video to learn more about spermatogenesis:

Attributions

- Sperm by Gilberto Santa Rosa licensed CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- sperm anatomy by Anatomy & Physiology OpenStax CNX. CC BY 4.0 via lumen learning

- spermatogenesis and seminiferous tubule by OpenStax College licensed CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia.org

- Human semen in a Petri dish by Digitalkil, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Homework by Tony Alter, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0