17.4: Blood Vessels

- Page ID

- 16826

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Why do bodybuilders have such prominent veins? Bulging muscles push surface veins closer to the skin. Couple that with a virtual lack of subcutaneous fat, and you have bulging veins as well as bulging muscles. Veins are one of three major types of blood vessels in the cardiovascular system.

Types of Blood Vessels

Blood vessels are part of the cardiovascular system that transports blood throughout the human body. There are three major types of blood vessels: veins, arteries, and capillaries.

Arteries are defined as blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart. Blood flows through arteries largely because it is under pressure from the pumping action of the heart. It should be noted that coronary arteries, which supply heart muscle cells with blood, travel toward the heart but not as part of the blood flow that travels through the chambers of the heart. Most arteries, including coronary arteries, carry oxygenated blood, but there are a few exceptions, most notably the pulmonary artery. This artery carries deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs, where it picks up oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. In virtually all other arteries, the hemoglobin in red blood cells is highly saturated with oxygen (95-100 percent). These arteries distribute oxygenated blood to tissues throughout the body.

The largest artery in the body is the aorta, which is connected to the heart and extends down into the abdomen (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The aorta has high-pressure, oxygenated blood pumped directly into it from the left ventricle of the heart. The aorta has many branches, and the branches subdivide repeatedly, with the subdivisions growing smaller and smaller in diameter. The smallest arteries are called arterioles.

Veins

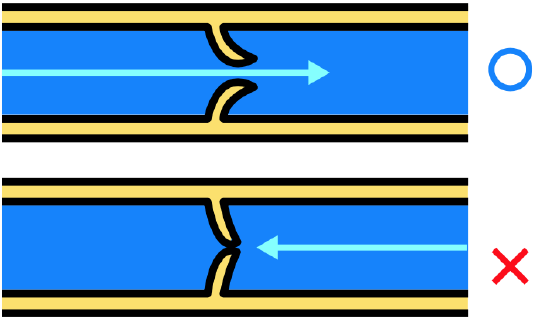

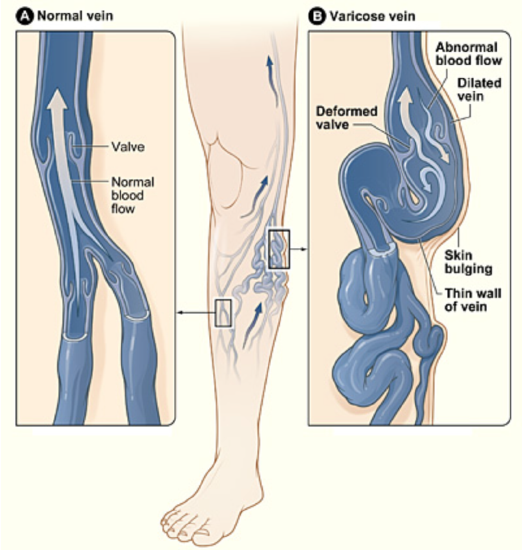

Veins are defined as blood vessels that carry blood toward the heart. Blood traveling through veins is not under pressure from the beating heart. It gets help moving along by the squeezing action of skeletal muscles, for example, when you walk or breathe. It is also prevented from flowing backward by valves in the larger veins, as illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Veins are called capacitance blood vessels because the majority (about 60 percent) of the body’s total volume of blood is contained within veins.

Most veins carry deoxygenated blood, but there are a few exceptions, including the four pulmonary veins. These veins carry oxygenated blood from the lungs to the heart, which then pumps the blood to the rest of the body. In virtually all other veins, hemoglobin is relatively unsaturated with oxygen (about 75 percent).

The two largest veins in the body are the superior vena cava, which carries blood from the upper body directly to the right atrium of the heart, and the inferior vena cava, which carries blood from the lower body directly to the right atrium. The inferior vena cava is labeled in the figure below. The superior vena cava is not labeled in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) but is clearly visible entering the right atrium of the heart. Like arteries, veins form a complex, branching system of larger and smaller vessels. The smallest veins are called venules. They receive blood from capillaries and transport it to larger veins. Each venule receives blood from multiple capillaries.

Capillaries

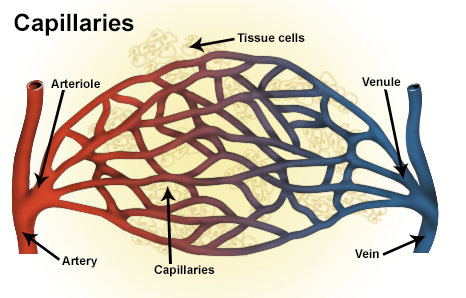

Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels in the cardiovascular system. They are so small that only one red blood cell at a time can squeeze through a capillary, and then only if the red blood cell deforms. Capillaries connect arterioles and venules, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Capillaries generally form a branching network of vessels, called a capillary bed, that provides a large surface area for the exchange of substances between the blood and surrounding tissues.

Structure of Blood Vessels

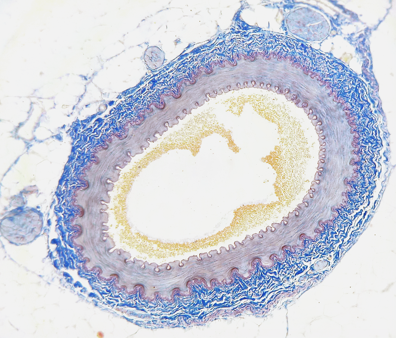

All blood vessels are basically hollow tubes with an internal space, called a lumen, through which blood flows. The lumen of an artery is shown in cross-section in the photomicrograph below. The width of blood vessels varies, but they all have a lumen. The walls of blood vessels differ depending on the type of vessel. In general, arteries and veins are more similar to one another than capillaries in the structure of their walls.

Walls of Arteries and Veins

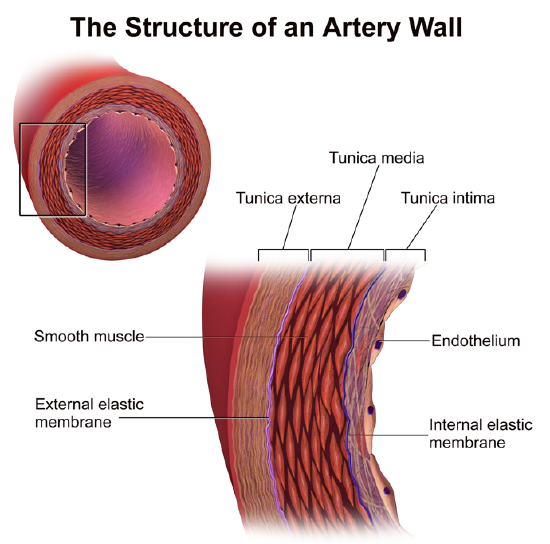

The walls of both arteries and veins have three layers: the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. You can see the three layers for an artery in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

- The tunica intima is the inner layer of arteries and veins. It is also the thinnest layer, consisting of a single layer of endothelial cells surrounded by a thin layer of connective tissues. It reduces friction between the blood and the inside of the blood vessel walls.

- The tunica media is the middle layer of arteries and veins. In arteries, this is the thickest layer. It consists mainly of elastic fibers and connective tissues. In arteries, this is the thickest layer because it also contains smooth muscle tissues, which control the diameter of the vessels.

- The tunica externa (also called tunica adventitia) is the outer layer of arteries and veins. It consists of connective tissue and also contains nerves. In veins, this is the thickest layer. In general, the tunica externa protects and strengthens vessels and attaches them to surrounding structures.

Capillary Walls

The walls of capillaries consist of little more than a single layer of epithelial cells. Being just one cell thick, the walls are well suited for the exchange of substances between the blood inside them and the cells of surrounding tissues. Substances including water, oxygen, glucose, and other nutrients as well as waste products such as carbon dioxide can pass quickly and easily through the extremely thin walls of capillaries.

Blood Pressure

The blood in arteries is normally under pressure because of the beating of the heart. The pressure is highest when the heart contracts and pumps out blood, and lowest when the heart relaxes and refills with blood. (You can feel this variation in pressure in your wrist or neck when you count your pulse.) Blood pressure is a measure of the force that blood exerts on the walls of arteries. It is generally measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) and expressed as a double number: a higher number for systolic pressure when the ventricles contract; and a lower number for diastolic pressure when the ventricles relax. Normal blood pressure is generally defined as less than 120 mm Hg (systolic)/80 mm Hg (diastolic) when measured in the arm at the level of the heart. It decreases as blood flows farther away from the heart and into smaller arteries.

As arteries grow smaller, there is increasing resistance to blood flow through them because of the friction of the blood against the arterial walls. This resistance restricts blood flow so less blood reaches smaller, downstream vessels, thus reducing blood pressure before the blood flows into the tiniest vessels, the capillaries. Without this reduction in blood pressure, capillaries would not be able to withstand the pressure of the blood without bursting. By the time blood flows through the veins, it is under very little pressure. The pressure of blood against the walls of veins is always about the same and normally no more than 10 mm Hg.

Vasoconstriction and Vasodilation

Smooth muscles in the walls of arteries can contract or relax to cause vasoconstriction (narrowing of the lumen of blood vessels) or vasodilation (widening of the lumen of blood vessels). This allows the arteries — especially the arterioles — to contract or relax as needed to help regulate blood pressure. In this regard, the arterioles act like an adjustable nozzle on a garden hose. When they narrow, the increased friction with the arterial walls causes less blood to flow downstream from the narrowing, resulting in a drop in blood pressure. These actions are controlled by the autonomic nervous system in response to pressure-sensitive sensory receptors in the walls of larger arteries.

Arteries can also dilate or constrict to help regulate body temperature by allowing more or less blood to flow from the warm body core to the body’s surface. In addition, vasoconstriction and vasodilation play roles in the fight-or-flight response, under the control of the sympathetic nervous system. For example, vasodilation allows more blood to flow to skeletal muscles and vasoconstriction reduces blood flow to digestive organs.

The lumpy appearance of this man’s leg is caused by varicose veins. Do you have varicose veins? If you do, you may wonder whether they are a sign of a significant health problem. You may also wonder whether you should have them treated, and if so, what treatments are available. As is usually the case, when it comes to your health, “knowledge is power.”

First, the “back story:” varicose veins are veins that have become enlarged and twisted because their valves have become ineffective (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). As a consequence, blood pools in the veins and stretches them out. Varicose veins occur most frequently in the superficial veins of the legs, but they may also occur in other parts of the body. They are most common in older adults, females, and people who have a family history of the condition. Obesity and pregnancy also increase the risk of developing varicose veins. A job that requires standing for long periods of time, chronic constipation, and long-term alcohol consumption are additional risk factors.

Varicose veins usually are not serious. In many people, they are only a cosmetic issue. However, in severe cases, varicose veins may cause pain and other problems. For example, the affected leg(s) may feel heavy and achy, especially after long periods of standing. Ankles may become swollen by the end of the day. Minor injuries may bleed more than normal. The skin over varicosity may become red, dry, and itchy. In very severe cases, skin ulcers may develop.

If you are concerned about varicose veins, call them to the attention of your doctor, who can determine the best course of action for your case. There are many potential treatments for varicose veins. Some of the treatments have potential adverse side effects; and with many of the treatments, varicose veins may return. Which treatment is best for a given patient depends in part on the severity of the condition.

- If varicose veins are not serious, then conservative treatment options may be recommended. These include avoiding standing or sitting for long periods, frequently elevating the legs, and wearing graduated compression stockings.

- For more serious cases, less conservative but non-surgical options may be advised. These include sclerotherapy, in which medicine is injected into the veins to make them shrink. Another non-surgical approach is endovenous thermal ablation. In this type of treatment, laser light, radio-frequency energy, or steam is used to heat the walls of the veins, causing them to shrink and collapse.

- For the most serious cases, surgery may be the best option. The most invasive surgery is vein stripping, in which all or part of the main trunk of a vein is tied off and removed from the leg while the patient is under general anesthesia. In a less invasive surgery, called ambulatory phlebectomy, short segments of a vein are removed through tiny incisions under local anesthesia.

Review

- What are the blood vessels? Name the three major types of blood vessels.

- Describe arteries. Identify the largest artery in the body.

- How are veins defined? What are the two largest veins in the body?

- Compare and contrast how blood moves through arteries and veins.

- What are capillaries, and what is their function?

- Compare and contrast the structure of the walls of arteries, veins, and capillaries.

- What is blood pressure, and how is it expressed? What blood pressure is considered normal?

- Identify the functions of vasoconstriction and vasodilation of arteries.

- Does the blood in most veins have any oxygen at all? Explain your answer.

- True or False. Only one red blood cell can pass through the lumen of a capillary at a given time.

- True or False. The pulmonary artery carries oxygenated blood.

- Which tissue in blood vessels is responsible for vasodilation and vasoconstriction? Where is it located?

- The blood pressure at the arterioles is generally _________ the blood pressure at the aorta.

A. lower than

B. higher than

C. the same as

D. not related to

- Explain why it is important that the walls of capillaries are very thin.

- Most of the blood in the body is in the:

A. Capillaries

B. Arteries

C. Heart

D. Veins

Explore More

Attributions

- Fist Pump by istolethetv licensed CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Arterial System by LadyofHats; public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Venous valve by Was a bee; Vectorized by ZooFari; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Venous system by LadyofHats, Mariana Ruiz Villarreal; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Capillaries by National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Artery by Lord of Konrad licensed CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Structure of artery wall by Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. licensed CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Leg before; public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Varicose Veins by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0