1.4: Ethical Reasoning and Conservation Planning

- Page ID

- 110290

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)I have purposely presented the land ethic as a product of social evolution because nothing so important as an ethic is ever “written.” . . . It evolves in the minds of a thinking community.

—Aldo Leopold, The Land Ethic, A Sand County Almanac

- Identify ethical dilemmas, intrinsic and extrinsic values, and value chains.

- Distinguish between normative and factual statements in an ethical argument.

- Compare and contrast common ethical theories and advantages and disadvantages.

- Recognize ethical dilemmas common to managing different types of fisheries and conserving rare and endangered species.

- Examine our personal values and how they influence our ethical norms.

- Identify the ethical principles involved in co-management and collaborative planning.

- Examine different ethical codes of conduct.

- Apply ethical reasoning steps in issues involving uses of fish.

4.1 Ethical Questions and Practical Ethics

Ethics involves deliberating about the moral principles that inform (or should inform) our actions. The human and natural worlds are too complex to expect easy-to-identify rules and absolute truths to guide our actions. In our modern world, people follow many different ethical theories to help them identify what actions are right. Ethical thinkers are needed today more than ever to help us understand our own and each other’s ethics and work together to develop policies for humans to coexist with each other and fish in natural and human-altered ecosystems.

In policy making, just as in our personal lives, we are often faced with a difficult choice between two possible moral imperatives, neither of which is clearly acceptable nor preferable. For example, regulating the take from a fish population to conserve options for future generations conflicts with the moral imperative of freedom to pursue fishing without restriction. The complexity arises because following one moral imperative (freedom) would result in transgressing another (conservation). For example, is it ever acceptable to kill one animal in order to save another (e.g., kill sea lamprey to protect more valuable fish)? Is it acceptable to displace people from their local community to create a protected area to save an endangered species? Should we kill all nonnative trout to restore a unique population of Cutthroat Trout? How do you restrict access to fishing to maintain productivity of fish and provide livelihood opportunities for future generations? Should we compensate for salmon losses at hydroelectric projects with mass release of hatchery-reared salmon from large-scale artificial production facilities? Should you eat farmed fish raised in cages or wild-caught fish?

Depending on your needs, preferences, and interests, you may differ in how you answer these questions. Our conscience is that inner feeling or voice that guides us to a morally right behavior, yet when two actions with morally laudable goals conflict, we have an ethical dilemma. In these cases, explicit consideration of values at stake should be part of careful debate about human involvement and what constitutes good or bad interventions. The explicit application of ethical principles while considering the opportunities, constraints, and interests is what we refer to as practical ethics.

Can you characterize your prevailing use of fish? Do you consider fish to be primarily valuable to you as a source of food, sport, livelihood, cultural or spiritual connections, or are there other ways that you value fish?

4.2 Values

Philosophers provide us with many useful tools to help us think through these questions. Though they often disagree on their theories and answers to very difficult questions, there is surprising agreement on what we need to do morally in our everyday life. An essential tool we use to explore moral choices and dilemmas is to distinguish different types of values.

Intrinsic values lie at the very heart of ethics. When we speak of the value a fish has in and of itself, we are speaking of its intrinsic value. Many philosophers maintain that all animals have some type of intrinsic value in themselves, irrespective of their usefulness to other animals (human or otherwise), such as the beauty of a sailfish. The opposite of intrinsic value is extrinsic value (also called use or instrumental values), such as the value we place on a highly palatable food fish because it is useful for eating. Fish, lobsters, crabs, and oysters all have extrinsic value to various people because they eat them, enjoy delicious flavors, and are provided with valuable livelihoods and economic benefits.

It is common for fish to hold both intrinsic and instrumental values. For example, marlin have very high extrinsic value when used in sashimi and in big game fishing. They also have a high intrinsic value because of their unique size, power, and rareness among offshore fish. Table 4.1 shows many different types of values, categorized into instrumental and intrinsic values.

| Value | Examples |

|---|---|

| Instrumental | |

| Food | Prevents hunger with lean protein, low in saturated fat |

| Nutrition | Lowers risk of heart disease and hypertension and source of calcium, phosphorus, niacin, vitamin B-12, and omega-3 fatty acids |

| Products | Fish oils, fish meal, glue, biofuels, candles, gelatin, isinglass, biopolymers, bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator, cosmetics, biomedicine, tools, apparel, jewelry, musical instruments, souvenirs (Olden et al. 2020) |

| Livelihood | Employing workers in capture fisheries, aquaculture, recreational tourism, and boats and fishing tackle |

| Recreation | Pleasure, competition, sport, pets, aquarium and pond displays |

| Culture | Music, cooking, and products that are related to local fish and fishing traditions |

| Art | Depictions of fish from ancient Egypt to the present, reflecting importance of fish |

| Ecological | Regulating nutrient cycles and disease vectors, biological control |

| Educational | Examples of vertebrate evolutionary change, specimens for laboratory dissection |

| Scientific | Medaka and zebra fish are research models for laboratory studies of genetics and developmental biology |

| Intrinsic | |

| Spiritual | Fish offerings to gods, symbols (Ichthys, Figure 4.2) of the faithful not driven by passions |

| Art | Beauty of fish |

| Existence | Their existence has value in and of itself |

A problem arises when fish are viewed only as resources that provide benefits to humans—we are holding exclusively extrinsic or instrumental values. When fish are viewed only as resources for humans, we tend to overexploit fisheries and not conserve them for future human uses. When people overexploit a fishery, this is more of a problem of short-term thinking, or immediate needs, since they are destroying the fishery they presumably want to continue to use. The conservation movement arose to help ensure that we could maintain the use value of natural resources, including fisheries, for the long run for human uses.[1] A potential problem with viewing fish as having only use value is that management of fish for the long run can still have cascading ecological impacts that cause harm to the environment (e.g., salmon farms that spread disease to wild salmon populations and alter ecosystems from excess nutrients). Conservationists who recognize that these adverse impacts to the environment harm the use value of the environment have proposed actions to reduce those impacts.

Some argue that we must believe that fish and ecosystems have only intrinsic value so we do everything we can to protect them. Generally, a belief that something has only intrinsic value leads to the conclusion that we are not allowed to use it at all. For fish, then, if someone believes that they have only intrinsic value, the logical conclusion is that the use of fish for fishing and food should be banned because these are uses of fish. Some accept this conclusion, but it is unlikely that many people would accept this conclusion as reasonable. Fortunately, philosophers reasoned long ago that things with intrinsic value, such as our fellow humans, also have use value to each other through the work we do for each other. The problem is when a person’s intrinsic value—and our obligation to respect them—is violated by abusing how we use their work, through stealing their labor through wage theft or slavery, for example.

The Latin phrase abusus non tollit usum (“abuse does not cancel use”) in this case means that there is no justifiable reason to condemn all uses of fish because some individuals may overexploit them. Norton (2005) argued that people logically can and do believe that fish have only use value and still accept their obligation to protect fisheries and ecosystems, while others logically can and do believe that fish have both intrinsic and use value and support the same policies.

4.3 Ethical Obligations and Actions

Our understanding of ethics and fishing needs to recognize four categories of actions. These are (1) morally forbidden, (2) permissible, (3) obligatory, and (4) supererogatory. The first three consider the actions that are easily understood as right or wrong or good or bad. Supererogatory actions are acts that are morally praiseworthy but not morally obligatory or beyond the call of duty. Most ethical dilemmas involve distinguishing two very different types of moral obligations: direct obligations and indirect obligations. Disagreements over beliefs in intrinsic versus extrinsic values can become quite vehement, and they can prevent us from finding agreement that we both want to protect fish. Likewise, disagreements over whether we have direct moral obligations to fish to protect them, or whether we have indirect moral obligations to protect them, too often get in the way of realizing that we both believe we have moral obligations to protect fish. Let’s examine these definitions so we can figure out how to find agreements when possible.

Direct obligations are defined as those we have directly to a fish, usually because we believe that a fish has some type of intrinsic value that gives it direct moral considerability. People have widely differing views about the intrinsic value of fish, as a result of having different views about the facts concerning whether or not fish can feel pain similar to people and can make plans and suffer if they don’t get to fulfill those plans.

For example, if we believe that a fish has the capacity to feel pain similarly to humans, then we would generally conclude that fish require our moral consideration regarding pain. They are in our moral circle for feeling pain. The moral consideration can be said to be a direct moral obligation to avoid causing it pain similar to human pain. Likewise, if we think that fish create long-term plans like humans and that fish feel some kind of mental loss and suffering from not executing those plans, then we can logically conclude that we have a direct moral obligation to fish to allow them to fulfill their plans. In this situation, it is logical that fish can both feel pain similarly to humans and suffer from not fulfilling their plans, so we have stronger direct moral obligations to fish. These obligations depend on the capacity of fish to feel pain similarly to humans or to have aims like humans and feel mental loss like humans. This relationship of facts and intrinsic value and moral obligations is important to understand, since people have very different beliefs about the facts, and science is making new discoveries. What if we disagree that fish can feel pain similarly enough to humans to require our moral consideration? If they can’t feel pain like that, but they are under stress due to an aquatic habitat that is so polluted by heat, nutrients, or lack of food that they die, do we have some type of obligation to them? This is where the concept of an indirect moral obligation is helpful.

Indirect moral obligations are those that we must fish because we have direct obligations to something else (usually humans) to protect the fish. For example, most people believe we have a moral obligation to sustainably protect fisheries so other humans have access to fisheries for economic and food benefits they provide. It is a direct obligation to other people to protect the fisheries. It is an indirect obligation to the fishery to protect it so we can fulfill our direct obligations to other people. This is a rather complex way to talk about our obligations, so why do it? It makes it easier to identify if we have agreement on whether or not we have any type of obligation to fish.

For example, if we believe we have a moral obligation (be it indirect or direct) to protect the many individual fish that comprise a fishery from dying from adverse environmental conditions, then we can agree that we need to eliminate those environmental conditions by passing policies to do so. Policies to reduce heat pollution or nonpoint source pollution can be supported by those who have different beliefs about intrinsic versus use values and direct versus indirect moral obligations. Similarly, we may disagree over whether or not any catching of fish that causes pain similarly to humans could be allowed, but progress would be made to reduce waste and bycatch. The effort, and habit, of finding commonalities in support for protection of fish is critical to passing policies that can be passed now, while laying groundwork for discussions on more sophisticated policies. As scientific research discovers facts about fish and other animals’ capacities to feel pain and make plans similarly to humans, we can identify how we can (or ought not to) fish in ways to meet our direct or indirect obligations to reduce suffering of fish.

An important concept in ethics concerns our moral obligations to act. We all likely have wondered if we are really obligated to perform an action that would help another person but would cost us greatly in terms of money, physical or mental or social harm, or our life. In ethics, an act is supererogatory if it is good but not morally required to be done. For example, let’s imagine that you conclude that the destruction of a fishery through overfishing is morally wrong and that you are obligated to help protect the fishery. Different ethical systems might conclude that you have slightly different moral obligations, but none would say that you needed to starve yourself to death rather that eat fish from such a fishery if that were your only way to survive. Neither would an ethical system require you to put your life in danger to stop a commercial fishing boat from fishing. Rather, they might require you to make sure that you purchase only from sustainable fisheries or to educate others and make efforts to change policies to stop overexploitation of fisheries. These latter obligations would meet the obligation to act without being supererogatory.

4.4 Burden of Proof in Value Systems

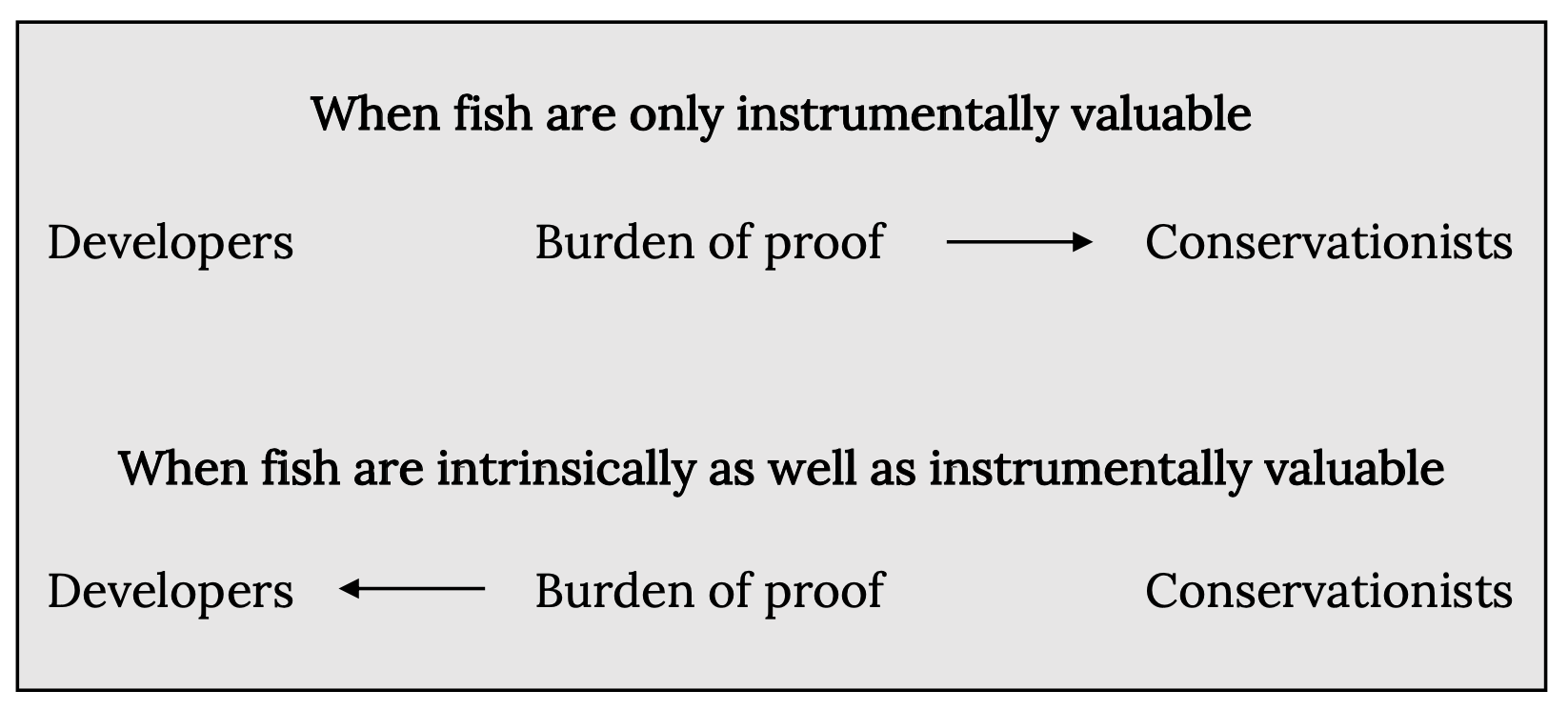

Now we turn to consideration of how beliefs in intrinsic or use value affect discussions about policies. An important difference between intrinsic and instrumental values that is relevant to fish conservation relates to who must demonstrate harm in disputes (Figure 4.1). For example, the burden of proof lies with the conservationists if values are only instrumental. On the other hand, if values are intrinsic as well as instrumental, the burden of proof will be on the fishers or others who are harming fish or their environment (Callicott 1995).

The diversity of values associated with fish and fishing complicates conservation. Two main approaches to conservation include (1) the wise use of nature and (2) the preservation of nature. These two approaches both reject the unthinking marginalization or destruction of nature. But when it comes to the actual management of fish, the two approaches differ. The wise-use approach aims to accommodate humanity’s continuous use of wild nature as a resource for food, oils, and other raw materials, as well as for recreation. The idea of wise use appeals to the best interests of humans, or to the interests of humans over time, including future people (this approach is often called “sustainable use”). The goal of management is to enhance and maintain nature’s yield as a valuable resource for human beings.

For the preservationist, on the other hand, the goal is to protect pristine nature, not to use it, carefully or otherwise. If human intervention has damaged wild nature (e.g., by pollution), then it is important to restore nature to something like its former state. From a preservationist perspective, wild places should be allowed to develop on their own with as little interference from humans as possible. The “otherness” or “naturalness” of the non-human world is what is most valued here. The only use allowed by humans in protected areas is for recreation, and this is only if recreation leaves no trace behind. Values beside resource values and the value of “untouched” nature have become increasingly important. These include the value of untouched nature, whole ecological systems, the value of species, and, in particular, the importance of animal welfare.

Preservationists tend to recognize that humans need to use natural resources to survive and thrive. So how do they reconcile the fact that humans need to use natural resources to survive while they are against using natural resources? Generally, it is by supporting the idea that humans should only use what is necessary for our welfare and to use natural resources in ways that protect nature.

4.5 Ethical Norms

When communicating about fishing and conservation issues, we should distinguish between normative and descriptive language. Descriptive language in ethics refers to observable facts about the world. Science can explain facts and descriptive patterns. For example, we know much about the behavior and competitive displacement of trout species and the effects of fishing on survival of fish. When we describe, not evaluate, the ethical beliefs of the public through interviews and surveys, our findings are descriptive ethics.

Normative language is used in ethics to make claims about how things should be, which actions are right or wrong, and so on. Ethical norms are patterns of behavior generally acceptable for a society, company, or organization. Norms reflect the way the group believes the world should be. The statement “Do not harvest juvenile fish” is a normative claim of fish conservationists. Norms may be formalized in policies, regulations, or standards of conduct. For example, when recreational anglers treat the fish they catch in a humane manner or avoid disturbing another angler’s fishing spot, they are following fishing norms.

However, deciding what is right or wrong involves consideration of values. David Hume (1711–1776) articulated the “is-ought” problems or the fact-value gap. His philosophical law maintains that one cannot make statements about what ought to be based on descriptive statements about what is. The NOFI (No-Ought-From-Is) idea that one cannot deduce an “ought” from an “is” means that we can make no logically valid arguments from the nonmoral (descriptive) to the moral (normative) without clearly introducing a normative argument. A much-needed skill in working with others is the ability to identify the facts and the values being used in discussions about conservation policy. When faced with a normative question, after the values that are sought are identified, then it is usually important to identify the facts of the situation.

Think about a favorite fish or a fish that you know well. Describe examples of the different ways in which the fish has value to you or others. Review Table 4.1 for types of values. Can you write a normative statement and a descriptive statement about this fish? Can you write a descriptive statement about the value of fish to someone other than yourself?

4.6 Where Do Ethics Come From?

Metaethics is a branch of philosophy that explores the foundations and existence of moral values. There are many different philosophical arguments for morality and ethics, some based on religious beliefs and some not. In this section, we explore various religious traditions and their environmental ethics toward fish. Those raised in the same religious tradition tend to hold common beliefs and follow common norms. In some religions, there are specific beliefs about values of fish and wildlife, and in other religions values are ambiguous. From the first book of Genesis, one gets a clear view of the prevailing Christian view of our relationship with fish and fowl until about the latter half of the 20th century (i.e., 1960s to 1990s).

And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion[2] over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

Genesis 1:26–28

During the latter half of the 20th century, coinciding with the rise of the environmental movement, the “greening” of Christianity led to a new mainstream view that did not focus on human domination of nature but rather on human stewardship of nature. It was based on the second book of Genesis.

Yahweh God took the man and settled him in the garden of Eden to cultivate and take care of it.

Genesis 2:15

In the Buddhist view, however, “One should not kill a living being, nor cause it to be killed, nor should one incite another to kill” (Nalaka Sutta, Sutta Nipāta III:11, 26–27). The fact that Buddhist teachings considered animals to have moral significance is evident in his condemnation of occupations that involve slaughtering animals (Saṃyutta Nikāya 19), instruction for monks to avoid wearing animal skins, and prohibition of behavior that intentionally causes harm to animals. A Buddhist-based tradition maintains that it is compassionate not to kill or harm animals. One should be compassionate. So, one should not kill or harm animals (Chengzhong 2014).

Buddhism believes in reincarnation and teaches us that all living beings around you can be or may have been your mother in a previous or next incarnation or life. The very animal you shoot may have been your friend in a previous life. Whether you believe in reincarnation or not, it is true that every being’s fate can once become your fate as well. There are no or very few hunters or fishers in Buddhist traditions. The only exception is killing in self-defense or in order to end its physical suffering when an animal is severely wounded.

Any well-functioning social group depends on ethical norms for behavior. These norms often reflect society and the collective beliefs and values of its citizens, and they may or may not reflect religion (Crabtree 2014; Guglielmo 2015). Major religions influence our perspectives about biodiversity conservation and hunting and fishing. Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Daoism (also known as Taoism), Buddhism, Jainism, Judaism, and Shinto are some religions practiced globally. Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest, continuously practiced religions, shaped Judaism, Christianity, and Islam with concepts of a single god, heaven, hell, and a day of judgment.

One of the oldest conservation tools for biodiversity conservation of ancient people practiced was to declare certain natural areas as sacred or taboo. Today, conservationists engage religious and other spiritually motivated communities for their support of and advocacy for marine protected areas (Schaefer 2017; Murray and Agyare 2018). Beliefs about what wild foods are permissible were derived by ancient religions. For example, Jews did not eat catfish because it was considered “unclean,” as it did not have fins and scales (Leviticus 11:19). According to the Shafi’i, Maliki, and Hanbali branches of Islam (Quran 2:173), “all fish and shellfish would be halal” (permissible to eat). Off the coast of Tanzania, fishers used dynamite, a very damaging technique, to harvest fish. Local Muslim sheikhs used passages from the Koran that promote pro-environmental behavior to convince the fishers that dynamite fishing was against Muslim teaching (Bauman et al. 2017).

Religions provide a long history of symbols associated with use and values of fish and fishing (Figure 4.2; Lynch 2014). Ichthys is a Christian symbol of a fish and signifies the person who uses it is a Christian. In Islam, according to the Quran, the fish is a symbol of eternal life and also of knowledge. In Hinduism, in the sect of Vaishnavism’s Supreme God (Vishnu) first appeared as Matsya, a fish that helped the first man survive the great flood.

What religious or cultural tradition(s) most influenced you during your childhood? How does your upbringing and early learning through your early social interactions influence your perspectives on fishing or conservation?

4.7 Ethical Theories: Schools of Thought

The ethical systems and conclusions that societies believe and act upon change over time for many reasons. The disadvantages of ethical systems lead philosophers to develop new ethical theories. Changing needs and scientific understandings lead to new conclusions about how to achieve the moral goals of each system. Because there are few clear ethical judgments, each of us needs to take ownership of our ethical beliefs—sometimes referred to as first-person ethics (Elliott 2006).

In Western philosophy, three traditions dominate ethical reasoning: virtue theory, deontological or duty-based theories, and teleological or consequentialism. Here I summarize these, in addition to ethical pragmatism and ethics of caring. The three schools are virtue ethics, consequentialist ethics, and deontological or duty-based ethics. Virtue ethics can be traced to Aristotle (384–322 BCE) and involves aspiring to a set of virtues, avoiding vices, and finding the right balance among values.

Duty-based ethics (deontological) asks “What are my duties and obligations regarding the treatment of others?” Kant’s (1787, 1998) categorical imperative held that the rightness or wrongness of actions does not depend on their consequences but on whether they fulfill our duty. Duties are obligatory. Common duties include “respect for humanity,” because persons have intrinsic value and should not be treated as things merely to be used for the benefit of others.

Consequentialist ethics can be traced to David Hume, Jeremy Bentham (1789), and John Stuart Mill (1863). There are two types of consequentialist schools of thought: ethical egoism, which treats self-interest as the foundation, and utilitarianism. Utilitarianism aims to bring about the greatest good for the greatest number of people or the greatest balance of good over evil. Actions are right if they tend to promote happiness (more formally, well-being), wrong if they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. Unfortunately, much critique of Mill did not recognize that his utilitarianism also profoundly advocated that individual liberty and strong government to promote education and culture were the foundation to promoting well-being, and that he was a strong abolitionist and suffragist (Mill 1859, 1975; Eggleston and Miller. 2014).

The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. (Mill 1859, 10)

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. (Spock, Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan)

Moral relativism is the view that judgments are true or false only relative to some standpoint (for instance, that of a culture or a historical period) and that no standpoint is uniquely privileged over all others. Although the public may understand the concept, moral relativism is discredited among philosophers.

Pragmatic ethics was developed by William James and John Dewey at the turn of the 20th century to synthesize the best of prior ethical theories and to approach ethics more scientifically. From virtue theory, it recognized that character was very important; from duty-based theory it drew the importance of gradually changing society by keeping the best of the old and improving with new understandings. From utilitarianism, it focuses on the actual consequences of our actions. It emphasized the use of emotion, evidence, and reason when individuals were confronted with an actual situation that required a moral choice. Pragmatism focused on guiding people to consider the real choices that were possible to them and the impacts those choices would have on other people (Dewey 1932). The moral rule can be summed up as making sure you take the time to gather evidence, reflect, and take actions that improve the good in a specific situation, including consideration of the long-term impacts of that action.

Each school of ethics has advantages and disadvantages. We must consider these when choosing the school of ethics we will use to help us make ethical decisions (Table 4.2).

Which ethical system (Table 4.2) do you prefer? Why?

| Type of theory | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Consequence-based

(Utilitarian) |

Stresses promotion of happiness and utility | Permits “tyranny of the majority,“ Mill (1859, 1975; p. 6) which ignores concerns of justice for the minority population |

| Duty-based (Deontology) | Stresses the role of duty and respect for persons | Underestimates the importance of happiness and social utility between different people |

| Feminist ethics of caring | Stresses caring in personal relationships, for animals and the environment | Unequal moral consideration of others (friends and family cared for more than others) |

| Pragmatism | Simple moral rule—improve individual and social well-being, use science to achieve | Requires individuals to take responsibility for moral reasoning |

| Contract-based (rights) | Provides a motivation for morality | Emphasized individualism, offers only a minimal morality |

| Character-based (virtue) | Stresses moral development and moral education | Depends on homogeneous community standards for morality |

| Ethics of caring | Highlights the differences between men’s and women’s situations in life | Differs from most Western traditions and many may not relate to orientation of caring |

4.8 Comparing Ethical Theories and Their Use

The ethical theories developed and modified over time have been used and abused in many ways. As noted above, their abuse does not prohibit their proper use. Like the physical and biological sciences, doing ethics well requires study and practice. In this section I briefly address which ethical theories are in common use in the last one hundred years and how they have been used or abused.

Figure 4.3 provides another way to understand the relationship of ethical theories. It makes no judgment as to which is better or worse.

On the left side of the figure is ethical egoism, a form of consequentialism. Ethical egoism is widely regarded as a very weak ethical theory, antithetical to ethics, since it does not guide action to consider others. In short, any ethical theory that argues that it is good to be inconsiderate of others doesn’t seem to be very ethical.

Utilitarianism is applied frequently in fish conservation and dominates the public policy arena. Utilitarianism is the basis of contemporary economic theories, which commonly hold or assume that individuals are best served when they are able to pursue and satisfy their preferences within a free market. Utilitarianism is often justified because (1) happiness does matter, (2) flexibility is important, (3) it appeals to our commonsense intuitions, and (4) it ensures equal consideration of all interests. Utilitarianism, like most ethical theories, is not a practical approach when individuals differ in how they measure utility or happiness, in identifying duties in a specific situation, or on what is virtuous (pluralism). As an example of how consequentialism is often misinterpreted, John Rawls, one of the most famous and influential political philosophers in the 20th century, did not recognize utilitarianism’s founding principle of the need to respect individual liberties. Rawls (1971) and Cochrane (2000) criticized utilitarianism for not considering how in many fisheries, justice, fairness, and rights may be more important than consequences.

Utilitarians may recognize human rights of those who fish (Ratner et al. 2014) and private ownership of fishing rights. Conservationist Roderick Haig-Brown (1939, 135) recognized that “When angling rights are privately owned, the owners spend a great deal of money on the preservation of value and restrict themselves and their friends to catches and practices that will ensure preservation.” In practice, in regulating harvest of fish, it is difficult to predict future responses to reduced harvest, and harvesters often adopt the “if-I-don’t-get-’em-somebody-else-will” philosophy.

Duty-, rights-, and responsibility-based ethics tend to ignore crucial ethical questions, such as: “What is the best life for me?” “How do I go about living?” or “What actions will make a better society?” These questions are the focus of ethics of character, or virtue ethics. Proponents of virtue ethics focus on actions and character (Taylor 2002; Sandler and Cafaro 2005; Westra 2005). A virtue ethics approach can and often does inform best practices for welfare in aquariums and fish farms and in codes of angler ethics. It does so by guiding us to ask what a virtuous person would do in various situations. In ordinary situations, like whether or not we should treat animals and fish well, it and most other ethical theories agree that yes, we should treat them well.

In contrast to the Western philosophies of moral reasoning, ethics of indigenous peoples and ecological feminism focus on ethics of caring. Many indigenous peoples follow an ethic of care for all kinds of others, as well as the complex value of ecological interdependencies (Figure 4.3; Gilligan 1982; Whyte 2015; Whyte and Cuomo 2016). Ecological feminism often focuses on the ethics of care and links their analysis to beliefs about gender roles in patriarchy (Gilligan 1988). Gilligan argues that many commercial and subsistence fisheries are based on male-dominated decision making, and the role and contributions of females in the fisheries is undervalued (Thompson 1985; Frangoudes and Gerrard 2018). Care ethics maintains that ethical living depends on mutually beneficial caring relationships that do not exploit the caregivers and value animals and dependencies (Gaard and Gruen 1993).

4.9 Ethics and the Expanding Moral Circle

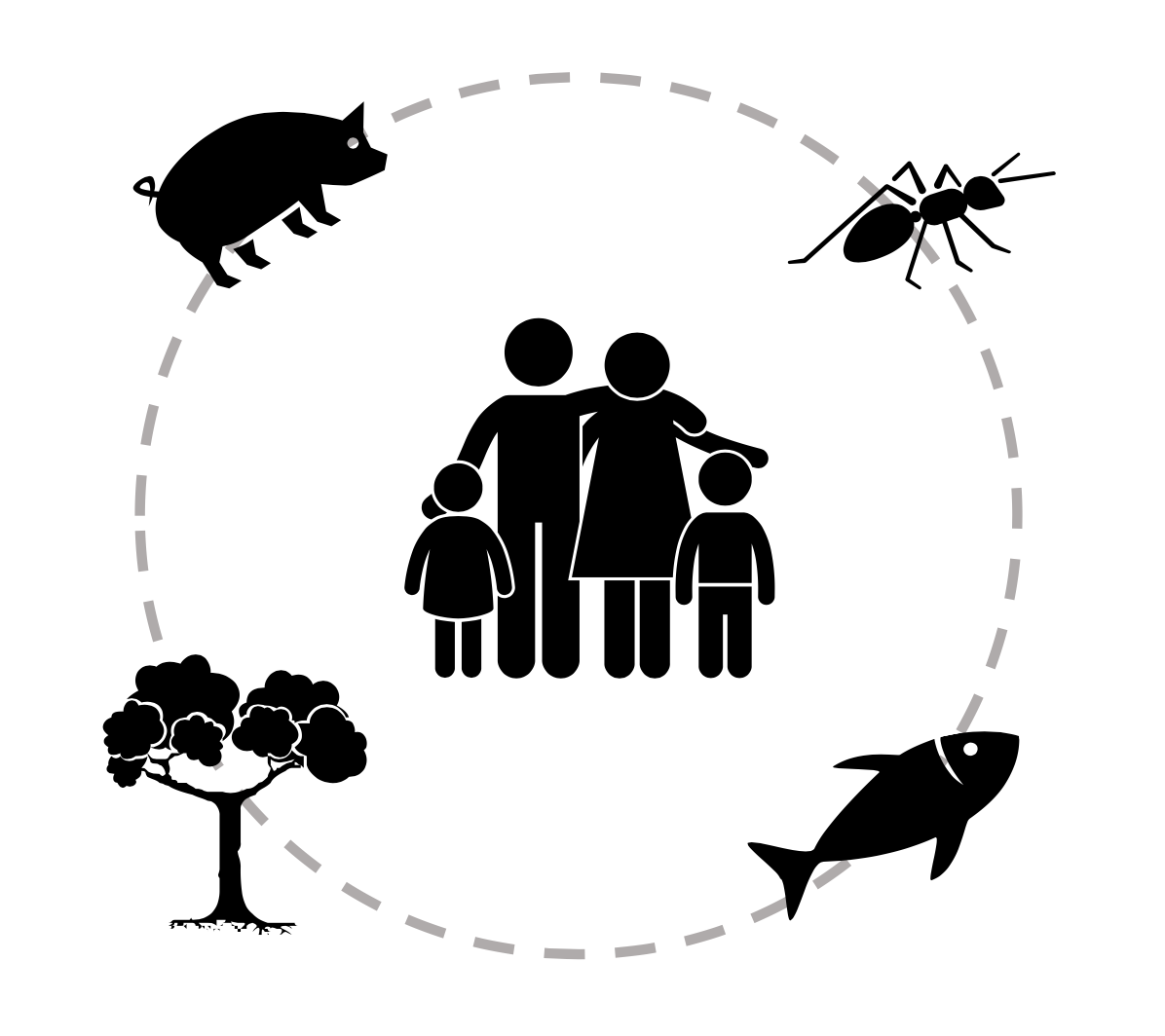

Over the course of human history, more and more beings in the world have been deemed to be worthy of serious moral consideration (Singer 2011a). The boundary drawn around those entities in the world deemed worthy of moral consideration, referred to as the moral circle, has expanded (Figure 4.4). Many people think that sentience, the ability to feel sensations like pain and pleasure, determines membership in our moral circle. If that’s the case, we need to ask what degree of sentience is required to make the cut?

Your personal beliefs about membership in the moral circle are likely a product of your culture. Use your reasoning to think beyond your inherited biases. For example, those raised in the Jain religion have always included all animals and all of nature in the circle. Extending the moral circle led to concerns for animal welfare and a code of conduct in use of animals to reduce suffering of people and animals. Singer’s notion of the expanding circle proposes that our moral sense, though shaped by evolutionary forces to overvalue self, kin, and clan, can propel us on a path of moral progress, as ethical reasoning will force us to include larger circles of sentient beings in our ethical deliberations.

Question to ponder:

Consider who is part of your moral circle of consideration. Yourself, your family, and your siblings are at the center of the circle. Draw multiple circles around the center and describe considerations you use to consider whether humanity, members of your group, your neighborhood, the nation, mammals, birds, fish, insects, plants, ecosystems, and future human generations should be included. What ethical theories do you find to be most applicable in defining your moral circle of consideration?

4.10 Model of Ethical Reasoning

Moral education involves improving the ability to identify ethical issues and then make a justified choice of how to act. There are many ways to organize our ethical reasoning. Sternberg (2012) identified eight sequential steps that are involved in ethical reasoning:

- Recognize that there is an event to which to react,

- define the event as having an ethical dimension,

- decide that the ethical dimension is of sufficient significance to merit an ethics-guided response,

- take responsibility for generating an ethical solution to the problem,

- figure out what abstract ethical rule(s) might apply to the problem,

- decide how these abstract ethical rules apply to the problem so as to suggest a concrete solution,

- prepare for possible repercussions of having acted in what one considers an ethical manner, and

- act.

This model will be adopted in discussion of case studies described in subsequent chapters.

Your moral argument uses both normative and descriptive language and is organized as (1) premises, (2) general moral principle, and (3) conclusion. The premises on which you base your argument will be descriptive, factual statements, whereas the other parts of the moral argument are normative statements. Ethical reasoning assists us in participating in debates and policy deliberations as an individual or as members of a group. Adopting the ethical reasoning model in a formal way helps us prevent ethical drift—that is, the gradual erosion of standards when there is competition for time and resources or an organizational culture that tolerates ethical lapses.

Consider the many decisions related to fish and wildlife that are made by the Board of Game and Inland Fisheries in Virginia (see Virginia Code, Title 29.1 – Game, Inland Fisheries and Boating). Can you imagine any regulations regarding one of these articles having a significant ethical dimension? If so, what?

4.11 Ethical Perspectives Relevant to Fish and Fishing

Six perspectives consider common notions underlying ethical approaches to wild animals:

- A contractarian perspective. In this view, wild animals fall outside the moral circle and are viewed as a resource for human use.

- A utilitarian perspective. This view is a form of consequentialism taking into account everyone affected by decisions. Fish and wildlife can suffer, so they are inside the moral circle. Consequently, their welfare is taken into account in management decisions.

- An animal rights perspective. This view maintains that certain animals share similarities with humans that underpin moral rights, such as the ability to suffer, or for some, the fact that they are alive. Consequently, there are some things we may never do to them. We should not kill, confine, or otherwise interfere in the lives of wild animals unless necessary. It is neither our right nor our duty to cull or in other ways to manage wild animals. These are very complex theories with many variations.

- Respect for nature perspectives. This is an overlapping group of views on protecting values of naturalness itself, including whole species, ecosystems, and biodiversity. It was popularized by writings of Aldo Leopold (1949). The moral importance of individual animals depends on whether they promote or threaten environmental values. Keystone species are to be protected, while invasive species should be removed or killed. A popular quote from this perspective is, “Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise” (Leopold 1949).

- A contextual (or relational) view. This view emphasizes the nature of the human-animal relationships. For example, there are different relations, and therefore different moral obligations, to wild animals than there are to domestic animals (Palmer 2010).

- Hybrid or pluralist view. This view argues for creating a pragmatic and pluralistic ethical framework from which scientists and conservation managers can draw when complex moral questions arise. This pluralistic ethical framework incorporates different approaches to environmental and animal ethics (Minteer and Collins 2005; Norton 2005). In a pluralistic society, we can’t expect to persuade others on fundamental questions of the good and the right. We can, however, attempt to persuade them to adopt our views on policy by offering arguments that appeal to their fundamental values, even if we don’t share them.

The hybrid view may be considered practical ethics, which is ethics developed in the religious, legal, and medical arenas and focuses on the full range of moral values that inform our lives, such as what is right, good, just, and caring. Practical ethics looks to these and other moral concepts, as well as the empirical reality of individual cases, for guidance in making ethical decisions. By honoring the insights of many moral ideas and not a single ethical theory, practical ethics has a deep reservoir of concepts available to triangulate on the best understanding of a moral problem. These cases were described in three editions of Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics (2011b).

Among the six ethical perspectives described above, which are you most likely to agree with and which ones do you disagree with? Why?

Moral pluralism is the view that acknowledges the existence of multiple values (Marrietta 1993). There are different ways to think about and judge what is moral, especially including other voices that are often marginalized, (e.g., indigenous peoples and women [Warren 1982]). Callicott (1990) argues that personal worldviews must be challenged and, if needed, abandoned. In this way, we make moral progress and are not guilty of moral relativism. Recognition of moral pluralism is one of the founding principles in the United States, particularly Virginia, where the individual’s right to have their own religious and moral systems is part of the Constitution. Respecting other’s views provides the start to respectful discussion between people about what actions and policies we agree are right. Then we can either try to make those agreements in moral norms, or pass programs or laws to help enact them.

Clearly, some cultural practices may be wrong. The ancient ritual in which Buddhists free captive animals to generate positive karma through an act of kindness (i.e., compassionate release of prayer fish) has been changed over time to become a commercial enterprise in which people buy animals specifically to release them. For example, the practice of compassionate release of captive animals may not serve the needs of the animals released nor the receiving ecosystem (Actman 2017). This well-intended practice may, in fact, be a threat to many species (Everard et al. 2019).

Ethical reasoning is helpful as we identify our values, others’ values, and what ethical system is preferred. Many ethical systems have very similar recommendations for what to do in common situations. The public and professionals in fish and wildlife management and other professions can increase the good when they help themselves and others find agreement on what actions to take. Recognizing that the ethical theories that other people hold have useful views can help unravel moral questions and bring people into agreement by recognizing their contributions to solving ethical questions.

Relying on a utilitarian principle for managing a fish or wildlife population to maximize human welfare is unworkable without also considering the principle of justice or other theories of ethics that require us to ensure rights of others. For yourself, I suggest that what you think, say, and do are in sync so that your values and actions are consistent. In addition, we should seek ways to respect the views of others and improve our ability to find agreement on how to protect people and fisheries.

4.12 Codes of Ethics

Ethical codes are specific codes of ethics adopted by or on behalf of professions (e.g., psychologists, doctors, wildlife professionals) or other practitioners to guide the behavior of members, interactions among members, and interactions between members and the public. In the context of a code adopted by a profession or by a governmental or quasi-governmental organization to regulate that profession, an ethical code may be styled as a code of professional responsibility, which informs about difficult issues of what behavior is “ethical.”

There are many forms of fishing practiced worldwide and, consequently, many ethical codes. Similarly, ethical codes exist for recreational anglers (http://www.ethicalangler.com/the-code-of-ethical-angling.html), fly fishers (https://flyfishersinternational.org/Resources/Educational-Resources/Code-of-Angling-Ethics), and commercial fisheries (FAO 2010–2020). The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) adopted a Code of Professional Ethics that includes mandatory standards and an Ethics Board that reviews complaints (AZA 2017). Aquarium and pond keepers in Australia abide by a code of conduct.

What ethical codes have you learned or are expected to follow in your professional discipline or avocations? What difficulties do you anticipate regarding following these codes? What ethical theories provide the basis for the code of conduct for your discipline? You may wish to review ethical theories in Table 4.2 or online.

NOAA’s Fisheries Service (NMFS) adopted the following “Code of Angling Ethics” in cooperation with marine recreational fishing groups to implement the public education strategy (NOAA 1999).

The Ethical Angler:

- Promotes, through education and practice, ethical behavior in the use of aquatic resources.

- Values and respects the aquatic environment and all living things in it.

- Avoids spilling, and never dumps, any pollutants, such as gasoline and oil, into the aquatic environment.

- Disposes of all trash, including worn-out lines, leaders, and hooks, in appropriate containers, and helps to keep fishing sites litter-free.

- Takes all precautionary measures necessary to prevent the spread of exotic plants and animals, including live baitfish, into non-native habitats.

- Learns and obeys angling and boating regulations, and treats other anglers, boaters, and property owners with courtesy and respect.

- Respects property rights, and never trespasses on private lands or waters.

- Keeps no more fish than needed for consumption, and never wastefully discards fish that are retained.

- Practices conservation by carefully handling and releasing alive all fish that are unwanted or prohibited by regulation, as well as other animals that may become hooked or entangled accidentally.

- Uses tackle and techniques which minimize harm to fish when engaging in “catch-and-release” angling.

4.13 Management of Invasive Fishes

Often because of human modifications of waterways or intentional and accidental releases, many fish species develop large populations and cause excessive damage to ecosystems of native fish communities. These species are referred to by many terms, including invasive, introduced, translocated, exotic, alien, or pest. Debates persist on the need and approach to manage invasive fish. Invasive species cause harm as defined by human interests and/or ecosystems, and these harms must overwhelm rights of individual animals for control measures to be initiated. In two of three examples, the harm was high enough to result in large-scale destruction programs. Many species of carp of China were introduced to North America and expanded in population size and range, competing with native fish (Reeves 2019). Harvesting to reduce populations and electric and physical barriers to limit migration are two strategies employed to reduce populations of carp. When the Sea Lamprey entered the upper Great Lakes, the added mortality caused native lake trout populations to drop 98% in a few decades (Brant 2019). Large-scale poisoning of streams occupied by juveniles was initiated and continues annually to depress populations of the Sea Lamprey in order for native fish to recover. Recent research on pheromones revealed an approach to attract spawning Sea Lampreys so they could be trapped and removed, rather than using poisons. The Northern Snakehead, which was established in many waterways by intentional releases followed by population expansion, has been both reviled and targeted by recreational anglers. Researchers have failed to document significant harm that the Northern Snakehead causes to native fishes or economies. Rather, local recreational anglers found it to be another sportfishing target, despite regulations in Virginia and Maryland calling for anglers to kill any Northern Snakehead caught (Orth 2019). In October 2019, one Snakehead was found in Georgia. “Kill it immediately” was the initial advice to anglers, even those who practice catch and release and never kill their catch.

The Northern Snakehead case raised the ethical question of whether a state agency can require an angler to kill a fish. In the present day, a reconceptualization of the relationships between humans, translocated species, and ecosystems is warranted. In a reversal of past practice, the National Park Service has a program of killing for conservation in Yellowstone National Park. In this case, Lake Trout were introduced to Yellowstone Lake and threaten populations of native fish, including Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout (Koel 2017). We will see more cases in which humans must manage novel combinations of fish in ecosystems.

4.14 Ethical Fisheries

Fish are the last wild animals harvested commercially, and the importance of fish for providing essential protein for people around the world is substantial. Fisheries employ 260 million people, and fish are the primary protein source for ~ 40% of the world’s population (FAO 2018). Fisheries are managed by actions and interactions of government bodies, the market, and civil society (Lam and Pauly 2010). Government policies and the market seldom consider ethical issues unless they come up within public involvement processes in civil society and nongovernmental organizations. Consequently, many large fisheries are managed with the belief in the right of individuals to maximize their profits through their own initiative with minimum government interference. However, in an open fishery there are never enough fish for everyone to have all they can catch, and if fishers act independently in their own self-interest, the fishery will collapse.

The Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries sets out principles and international standards of behavior for responsible practices with a view to ensuring the effective conservation, management, and development of living aquatic resources, with due respect for the ecosystem and biodiversity (FAO 2010–2020, Pitcher et. al. 2009). The code recognizes the nutritional, economic, social, environmental, and cultural importance of fisheries and the interests of all stakeholders of the fishing and aquaculture industries. It considers the biological characteristics of the resources and their environment and the interests of consumers and other users.

For example, the management of many fisheries around the world is complicated by a complex global supply chain and, in some nations, weak governance. Government subsidies, bycatch, and employment vary greatly between commercial or large-scale fisheries and subsistence or small-scale management (Table 4.3; Lam 2016). Fisheries are sometimes managed by providing harvesters with individual transferable quotas or shares of the allotted catch. While this strategy provides for more efficient fisheries, the quotas are often unfairly distributed based on historical catches, which disadvantages small, subsistence coastal fishers. Yet small-scale, artisanal and subsistence fisheries generate about one-third to one-half of the global catch that is used for direct human consumption, and they employ more than 99% of the world’s 51 million fishers (Pauly and Zeller 2016; Jones et al. 2018).

| Fisheries Benefits | Large-scale | Small-scale |

|---|---|---|

| Annual landings for human consumption | ~ 60 million tonnes | ~ 27 million tonnes |

| Annual catch discarded at sea | 9 million tonnes | Almost none |

| Annual catch for industrial reduction to fishmeal & fish oil |

26 million tonnes |

Almost none |

| Fuel used per tonne of fish for human consumption | 10–20 million tonnes | 2–5 million tonnes |

| Number of fishers employed | 0.5 million | ~ 12 million |

| Government subsidies | 25–30 billion US $ | 5–7 billion US $ |

Canned tuna may be a cheap, nutritious, and healthy protein, but the activities along the global supply chain are often hidden from consumers. Some harvest methods are unsustainable and include government subsidies, high levels of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, and in some cases forced labor aboard fishing vessels (Couper et al. 2015; Urbina 2019). These hidden costs of canned tuna or other seafood products are not considered unless the product contains appropriate labeling (Fishwise 2015). Seafood certification, or ecolabeling, provided by third parties, such as the Marine Stewardship Council and Seafood Watch, attempt to certify ethical fisheries based on a variety of goals, including fair trade, worker welfare, habitat, and bycatch (Kittinger et al. 2017; Lam 2019).

Intensive and participatory management of fisheries dominates in many developed nations, which have the resources to invest in scientific data collection and stock assessment. Many previously overfished fish stocks subjected to low fishing pressure are now rebuilding in regions where fisheries are intensively managed (Hilborn et al. 2020). However, fisheries in developing countries are under intense pressure from increasing human populations, overharvest, and conflicts over access. Typically, there are too many small-scale fisheries, weak governments, and poor fisheries management.

Comanagement involves a shared management responsibility among government, fishing communities, and other stakeholders to develop a shared knowledge base and democratic decision making (Berkes et al. 2000; Viswanathan et al. 2003; Defeo and Castilla 2005; Gelcich et al. 2005; Armitage et al. 2009; Lam and Pauly 2010; Villanueva-Poot et al. 2017). When fishers facing common dilemmas form cooperative communication ties with direct resource competitors, they may achieve positive gains (Barnes et al. 2019). Comanagement is still in its infancy in the United States, although the Magnuson-Steven Act includes few barriers to it in developing fishery management plans (Emmett Environmental Law & Policy Clinic and Environmental Defense Fund 2016.). Organized opposition from agencies and special interests and difficulties in consensus building must be overcome to implement comanagement (Ayers et al. 2017). Comanagement is a gradual process that relies on voluntary involvement of diverse stakeholders, but the sharing of responsibilities can make fisheries more sustainable if benefits are greater than the costs to change (Arlinghaus et al. 2019; Hoefnagel et al. 2006). Collaborative governance is becoming more politically feasible as emerging social norms consider a broader range of values (Lam and Pauly 2010). Creating a social network of fishers with authority to comanage fisheries may lead to solutions to many problems, including the following:

- Tyranny of scale, which means that too many small fisheries spread over a wide geographic area and cannot be monitored at these small scales by a single management entity (Prince 2010).

- The integration of fishers’ knowledge and practices inform fishery management plans and research.

- Coordination and negotiation of agreements with wealthy nations and nations that subsidize fishing have more fleet capacity and dominate the fisheries.

- Reduction in unreported and illegal fish harvests occurs from efforts at self-enforcement.

- Fishing income is more equitably distributed among participants in the fishery.

- Reduce marginalization of subsistence fishers, thereby enhancing livelihoods and reducing behaviors that degrade the local environment (Robbins 2012).

- Fishing boats from wealthy nations are kept out of the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), reducing the stealing of fish from the poor (McCauley et al. 2018).

- People of small island states are most vulnerable to sea level rise and storm surges and depend entirely on fish for their protein. Yet, the USA and European Union contribute disproportionately to greenhouse gas emissions.

- Managing recreational fishing is tailored to specific anglers who have both catch- and noncatch-related motivations.

Effective public participation requires deliberation on issues by all those affected by a decision (Dewey 1927; Barber 2003), yet most fisheries’ management deliberations are done by governing boards. Board members are often appointed rather than elected and serve out of duty rather than interest. When the governing board is not forced to decide what is best for the whole, individuals may lapse into self-interest. In participatory comanagement, all stakeholders, not only harvesters, are present for discussing ethical issues of public trust, intergenerational equity, fishing rights, human welfare, social justice (exclusion), and freedoms (Lam and Pauly 2010; Lam and Pitcher 2012). This deliberative, democratic approach ensures that ethical issues along with economic factors, social policies, and political decisions are considered, as well as the condition of relevant ecosystems. In this way, environmental values and basic human interests (welfare, freedom, and justice) are considered (Lam 2016, 2019). Therefore, the ethical management of fisheries must address five moral imperatives:

- Avoid overexploitation and ensure long-term conservation in a just manner that enhances all people’s well-being;

- Allocate allowable harvest in a fair and equitable manner;

- Minimize restricted access to fishing areas;

- Enforce regulations with reasonable consequences; and

- Minimize or avoid fish welfare impacts of fishing practices and behaviors.

Requirements for ethical fisheries are summarized in Table 4.4 by components of the fishery and major ethical principles. Social justice is justice in terms of transparent decision making regarding the distribution of wealth and opportunities and privileges for fishers, other stakeholders, and consumers. Ecological justice requires putting the economy in its place as a subsystem within society and the wider natural world. Consideration of ecological justice recognizes that there are many more indicators of well-being beyond gross national product (Smith et al. 2013). The term distributive justice refers to fairness in the distributing benefits from a fishery and ecosystem.

| Subject | Objectives related to welfare (well-being) | Objectives related to freedom (autonomy) | Objectives related to justice |

|---|---|---|---|

| The ecosystem | Ecosystem integrity; habitat and biodiversity protection | Maintenance of capacity to change; resilience | Stewardship and interests represented by human institutions |

| Fish stocks | Stock and genetic conservation; animal welfare | No barriers to migration | Fair conditions for reproduction |

| Fisheries | Economic viability; sustainable development; safety on board | Conditional freedom to act | Cross-sectoral equity (in taxes and law); access to tribunals |

| Fishers and their communities | Adequate income and working conditions; poverty eradication; cultural diversity | Freedom to change or not; empowerment; cultural identity | Fair treatment in trade and law; equitable access to resources; compensation |

| Other stakeholders | No or reduced externalities from fishing | Freedom to compete | Equitable share of resources; dispute resolution |

| Consumers | Safe, nutritious, affordable food; societal efficiency | Availability of choice (e.g. labelling) | Equitable access to food; no barriers to trade; cross-sectoral equity |

| Politicians | Availability of alternative policy choices | Capacity to decide; free participation in public deliberation | Transparency; accountability; liability; public oversight |

Examination of the ethical matrix forces a fuller dialogue of the ethical principles important for different stakeholders (Lam and Pitcher 2012, Lam 2016, 2019). For example, government proposals to designate no-take marine reserves are intended to protect ecosystem integrity and the well-being or recovery of fish stocks. These benefits must be considered in the context of freedom and justice for fishers and fishing communities that are most affected by the designation (Jones 2009). Fishers will respond to such proposal with statements such as “Fishing is our way of life and our way of earning a living—it’s not just about money,” or “It’s not just the loss of an individual business if a fisherman leaves the industry, it’s the loss of the fishing culture, on which whole villages are dependent.” Another example includes proposals to grant property rights to fish stocks or fishing grounds. In these proposals, the consumer may benefit from a more efficient fishery and more affordable seafood. However, the freedom of certain fishers to fish will be lost, and equitable distribution of a quota must be considered. In developing countries, commonly needed fisheries reforms include justice issues, such as the evictions for coastal development, child labor, forced labor, unsafe working conditions, gender-based violence, and loss of fishing rights (Ratner et al. 2014). In small-scale, subsistence fisheries, governance systems that give fishers access rights provide strong incentives to engage in processes of data collection, assessment, and management (Prince 2010). Furthermore, the difficult tradeoffs can be made more easily in a collaborative, comanagement governance where stakeholders share knowledge and develop trusting relationships (Armitage et al. 2009).

The justice ethical principle states that decision makers should focus on actions that are fair to those involved. In most developed countries, about 1 in 10 people are recreational anglers. Should those individuals who are not recreational anglers be involved in policies related to fishing? License fees and excise taxes on equipment and motorboat fuels fund sportfishing programs. Faced with declining revenues, how should state agencies fund fish conservation?

4.15 Concluding Thoughts

To ensure that fish practitioners are aware of ethical principles that guide their actions, ethical reasoning should be incorporated into all curricula, major meetings, and conferences, and state and federal agencies should establish ethics components in agency operations and procedures (Hadidian et al. 2006). Teaching should focus on being ethical and not simply knowing ethical principles (Kretz 2015). Ethics of caring has yet to gain widespread acceptance for fish conservation. Other concepts, such as social justice, distributive justice, and ecosystem justice, rarely enter into the policy-making process. The capacity to make genuine moral judgments is grounded in emotional attachments (Andreou 2007) that are engaged by making deliberations with others who have opposing sentiments. Recognizing the role that emotions play permits us to involve both hearts and minds in deciding right actions.

Young students in particular are prone to be pessimistic and despair over the daunting challenges in fish conservation. We need to avoid both pessimism and idealistic optimism. Being optimistic about the strategies used will allow us to persist in difficult circumstances. As Clayton and Myers (2005, 206) put it, “Sometimes the fear that we can never make enough of a difference—ecosystems will perish anyway—prevents us from making the attempt.” If we continue to ignore discussing ethical concerns with all interested stakeholders, we risk alienating a large segment of the populace. Not all members of the public value fish or fishing in the same way as you might. Ignoring ethical issues will further erode the credibility and efficacy of management agencies, forcing citizens to adopt the public ballot initiative process to be heard (Loring 2017; Manfredo et al. 2017). Emerging global threats to biodiversity and shifts in distributions of many marine fish will necessitate new, more responsive models of governance (Holling and Meffe 1996; Knight and Meffe 1997; Free et al. 2020).

Profile in Fish Conservation: Mimi E. Lam, PhD

Mimi E. Lam is a researcher and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Alumna at the University of Bergen.

Mimi E. Lam (https://www.uib.no/en/persons/Mimi.E..Lam) studied theoretical chemistry and physics in university, earning a BSc honors degree at the University of British Columbia and a PhD from Dalhousie University. This academic background gives her unique analytical insights and methods to examine the complex interactions and underlying mechanisms governing both physical and human-natural systems. She tackles “wicked” societal problems in fisheries and marine governance, where a plurality of values prevents a unique problem definition or solution, with collaborative teams drawn from the academic and non-academic sectors. She examines how human values, beliefs, attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors influence our interactions with nature. Consequently, her investigations at the science-policy-society interface inform the decision-making of individuals, communities, and society in “post-normal” situations, where facts are uncertain, values are in dispute, stakes are high, and decisions are urgent. Mimi Lam’s innovation is designing deliberation and decision-support tools that promote both scientific and ethical reflection, evaluation, and analysis to inform robust policy decisions.

In her transdisciplinary approach to fisheries, Mimi Lam works across disciplines, sectors, and cultures, routinely engaging scholars from fisheries ecology, psychology, and philosophy, as well as stakeholders and citizens from local and indigenous communities, fishing industries, nongovernmental agencies, and governments. Past research papers have established Mimi as a leader in the transdisciplinary study of the ethics of seafood, value chains, and fisheries governance. She co-led an interdisciplinary team elucidating the diverse values and ecology of herring to help reconcile the Pacific herring fishery conflict in Haida Gwaii, British Columbia, Canada. At conflict were herring’s cultural value as traditional food for coastal indigenous peoples, socio-economic value in the commercial roe fishery, and ecological value as forage fish for predatory fish, marine mammals, and seabirds. Stakes were high and facts were contested when the federal government decided whether or not to reopen the herring fishery. Her team’s novel value- and ecosystem-based management approach combined practical ethics to elicit values with ecological modeling to evaluate impacts and risks to open conflicting stakeholders to dialogue and to inform a compromise on a feasible management strategy.

Currently Dr. Lam is leading a project in Norway called Managing Ethical Norwegian Seascape Activities (https://mensa.w.uib.no/), which focuses on how to reconcile the inherent value trade-offs and ethical dilemmas involved in managing seascape activities that encompass not only fisheries, but also aquaculture, oil and renewable energy production, shipping, transportation, tourism, and recreation. Seascape activities are diverse, complex, and dynamic human enterprises that may intersect spatially and/or temporally in the coasts and oceans. Different ways of knowing and valuing coexist, which can lead to management and policy conflicts that must be understood from numerous perspectives in order to effectively govern the marine resources and activities. Dr. Lam’s approach in managing fisheries and other seascape activities fosters the extremely difficult consideration of values and deliberations for improved understanding and trust among different participants (for example, among disciplinary experts, fisher and non-fisher, policy-maker and activist, male and female, and wealthy and poor). Her transdisciplinary approach recognizes and offers ethical deliberation and decision-support tools to reconcile the plurality of values and worldviews that exists in modern society and among individuals and cultural groups.

In summary, Mimi Lam champions scientific and ethical approaches to complex environmental and societal challenges that bring diverse parties and perspectives together to develop dialogue and trust, by accepting differences and embracing tolerance for other values and ways of knowing. She received the Conservation Beacon Award from the Society for Conservation Biology for “pioneering an ethical approach to the conservation of marine resources, both natural and cultural, through interdisciplinary research and community engagement at the science-policy interface.” The legacy of her influence will be to promote a more sustainable and ethical future by informing policies that support diverse voices and sustain the ways of life of indigenous peoples and local communities, productive fisheries, and resilient ecosystems.

Key Takeaways

- Ethical reasoning deals with values and whether actions are right or wrong.

- Ethical arguments consist of premises, moral principles, and conclusions.

- Success or failure in environmental problem solving is often determined by the way a problem is formulated and discussed in public discourse.

- Five approaches for ethical thinking that may guide decision making include (1) virtue theory, (2) deontological or duty-based theories, (3) teleological or consequentialism, (4) ethical pragmatism, and (5) ethics of caring.

- Ethical reasoning assists us in participating in debates and policy deliberations as an individual, member of a group, and as a member of society.

- Codes of ethics for fishing have been developed to encourage ethical behavior.

- Ethical fisheries can evolve only with dialogue and consideration of principles of freedom, equity, fairness, and justice.

- Collaborative governance is necessary for developing trust among stakeholders.

- When fishers facing common dilemmas form cooperative communication networks with direct resource competitors, they may achieve positive gains.

This chapter was reviewed by Mimi E. Lam and Dennis Scarnecchia.

URLs

Virginia Code, Title 29.1 – Game, Inland Fisheries and Boating: https://law.justia.com/codes/virginia/2014/title-29.1

Ethical theories: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uw7W1PpnbZQ

Long Descriptions

Figure 4.1: Arrow diagram showing that burden of proof is on conservationists when fish are instrumentally valuable and on developers when fish are intrinsically valuable. Jump back to Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.2: 1) Christianity, simple 2 line drawing of outline of a fish; Ichthys is an important identification symbol in Christianity; 2) Judaism, a painting of fish with other cooking ingredients; in Judaism, fish is a symbol of fertility and luck, and gefilte fish is a traditional dish; 3) Hinduism, a giant gray fish is larger than the boat it swims alongside filled with people; in Hinduism, Matsya, a fish is the first supreme god; 4) Islam, an older man stands atop a large fish, holding his hands in prayer; In Islam, fish is a symbol of eternal life and of knowledge. The mythical Al-Khidr is depicted here standing on the fish and using it to travel; 5) Buddhism, painting of 2 golden fish; in Buddhism, the golden fish are one of eight auspicious symbols; Daoism, drawing of 2 koi fish; in Daoism, the yin and yang is often illustrated with two koi fish. Jump back to Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.3: Ethical theories organizational chart; 1) Center line: Ethics of character; what sort of people should we be? leads to Aristotelianism, virtue is a mean between extremes of action and passion; 2) Left line: Ethics of conduct; what sort of actions should we perform? branches out to Consequentialism; the right action is the one that produces the most intrinsic good; Deontology; the good is defined independently of the right. Consequentialism branches out to for the agent: ethical egoism and for everyone affected: utilitarianism. Deontology leads to Kantianism; actions must satisfy the categorical imperative. 3) Right line: Ethics of caring branches out to ecological feminism and Indigenous peoples ethics. Jump back to Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.4: A circle made up of dashes encompasses human icons within it (adult male, adult female, male child and female child). on top of the dashes and outside the circle are a pig, an ant, a fish, and a tree. Jump back to Figure 4.4.