2.2: The Scientific Method

- Page ID

- 31602

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The scientific method is a process of research with defined steps that include data collection and careful observation.

Observation

Scientific advances begin with observations. This involves noticing a pattern, either directly or indirectly from the literature. An example of a direct observation is noticing that there have been a lot of toads in your yard ever since you turned on the sprinklers, where as an indirect observation would be reading a scientific study reporting high densities of toads in urban areas with watered lawns.

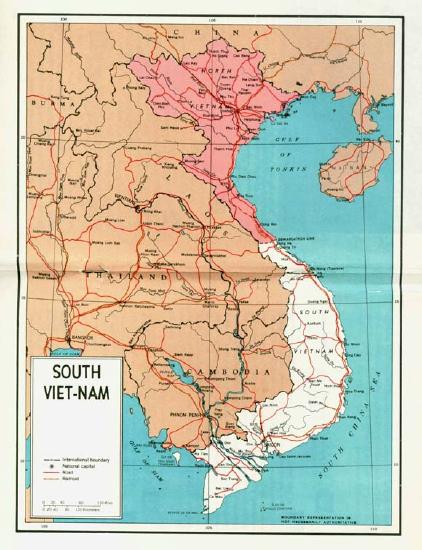

During the Vietnam War (figure \(\PageIndex{a}\)), press reports from North Vietnam documented an increasing rate of birth defects. While this credibility of this information was initially questioned by the U.S., it evoked questions about what could be causing these birth defects. Furthermore, increased incidence of certain cancers and other diseases later emerged in Vietnam veterans who had returned to the U.S. This leads us to the next step of the scientific method, the question.

Question

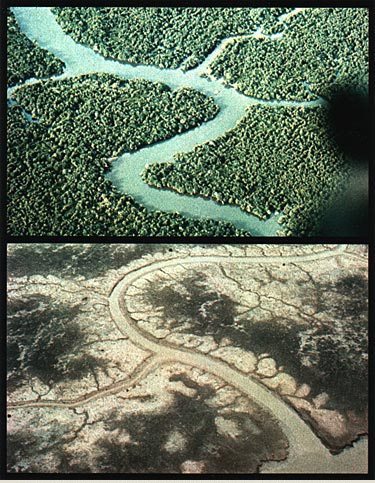

The question step of the scientific method is simply asking, what explains the observed pattern? Multiple questions can stem from a single observation. Scientists and the public began to ask, what is causing the birth defects in Vietnam and diseases in Vietnam veterans? Could it be associated with the widespread military use of the herbicide Agent Orange to clear the forests (figure \(\PageIndex{b-c}\)), which helped identify enemies more easily?

Hypothesis and Prediction

The hypothesis is the expected answer to the question. The best hypotheses state the proposed direction of the effect (increases, decreases, etc.) and explain why the hypothesis could be true.

-

OK hypothesis: Agent Orange influences rates of birth defects and disease.

-

Better hypothesis: Agent Orange increases the incidence of birth defects and disease.

-

Best hypothesis: Agent Orange increases the incidence of birth defects and disease because these health problems have been frequently reported by individuals exposed to this herbicide.

If two or more hypotheses meet this standard, the simpler one is preferred.

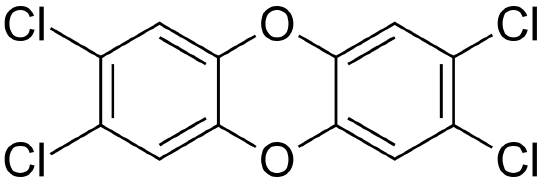

Predictions stem from the hypothesis. The prediction explains what results would support hypothesis. The prediction is more specific than the hypothesis because it references the details of the experiment. For example, "If Agent Orange causes health problems, then mice experimentally exposed to TCDD, a contaminant of Agent Orange, during development will have more frequent birth defects than control mice" (figure \(\PageIndex{d}\)).

Hypotheses and predictions must be testable to ensure that it is valid. For example, a hypothesis that depends on what a bear thinks is not testable, because it can never be known what a bear thinks. It should also be falsifiable, meaning that they have the capacity to be tested and demonstrated to be untrue. An example of an unfalsifiable hypothesis is “Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is beautiful.” There is no experiment that might show this statement to be false. To test a hypothesis, a researcher will conduct one or more experiments designed to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. This is important. A hypothesis can be disproven, or eliminated, but it can never be proven. Science does not deal in proofs like mathematics. If an experiment fails to disprove a hypothesis, then we find support for that explanation, but this is not to say that down the road a better explanation will not be found, or a more carefully designed experiment will be found to falsify the hypothesis.

Hypotheses are tentative explanations and are different from scientific theories. A scientific theory is a widely-accepted, thoroughly tested, and confirmed explanation for a set of observations or phenomena. Scientific theory is the foundation of scientific knowledge. In addition, in many scientific disciplines (less so in biology) there are scientific laws, often expressed in mathematical formulas, which describe how elements of nature will behave under certain specific conditions, but they do not offer explanations for why they occur.

Design an Experiment

Next, a scientific study (experiment) is planned to test the hypothesis and determine whether the results match the predictions. Each experiment will have one or more variables. The independent variable is what scientists hypothesize might be causing something else. In a manipulative experiment (see below), the independent variable is manipulated by the scientist. The dependent variable is the response, the variable ultimately measured in the study. Controlled variables (confounding factors) might affect the dependent variable, but they are not the focus of the study. Scientist attempt to standardize the controlled variables so that they do not influence the results. In our previous example, exposure to Agent Orange is the independent variable. It is hypothesized to cause a change in health (likelihood of having children with birth defects or developing a disease), the dependent variable. Many other things could affect health, including diet, exercise, and family history. These are the controlled variables.

There are two main types of scientific studies: experimental studies (manipulative experiments) and observational studies.

In a manipulative experiment, the independent variable is altered by the scientists, who then observe the response. In other words, the scientists apply a treatment. An example would be exposing developing mice to TCDD and comparing the rate of birth defects to a control group. The control group is group of test subjects that are as similar as possible to all other test subjects, with the exception that they don’t receive the experimental treatment (those that do receive it are known as the experimental, treatment, or test group). The purpose of the control group is to establish what the dependent variable would be under normal conditions, in the absence of the experimental treatment. It serves as a baseline to which the test group can be compared. In this example, the control group would contain mice that were not exposed to TCDD but were otherwise handled the same way as the other mice (figure \(\PageIndex{e}\))

In an observational study, scientists examine multiple samples with and without the presumed cause. An example would be monitoring the health of veterans who had varying levels of exposure to Agent Orange.

Scientific studies contain many replicates. Multiple samples ensure that any observed pattern is due to the treatment rather than naturally occurring differences between individuals. A scientific study should also be repeatable, meaning that if it is conducted again, following the same procedure, it should reproduce the same general results. Additionally, multiple studies will ultimately test the same hypothesis.

Results

Finally, the data are collected and the results are analyzed. As described in the Math Blast chapter, statistics can be used to describe the data and summarize data. They also provide a criterion for deciding whether the pattern in the data is strong enough to support the hypothesis.

The manipulative experiment in our example found that mice exposed to high levels of 2,4,5-T (a component of Agent Orange) or TCDD (a contaminant found in Agent Orange) during development had a cleft palate birth defect more frequently than control mice (figure \(\PageIndex{f}\)). Mice embryos were also more likely to die when exposed to TCDD compared to controls.

An observational study found that self-reported exposure to Agent Orange was positively correlated with incidence of multiple diseases in Korean veterans of the Vietnam War, including various cancers, diseases of the cardiovascular and nervous systems, skin diseases, and psychological disorders. Note that a positive correlation simply means that the independent and dependent variables both increase or decrease together, but further data, such as the evidence provided by manipulative experiments is needed to document a cause-and-effect relationship. (A negative correlation occurs when one variable increases as the other decreases.)

Conclusion

Lastly, scientists make a conclusion regarding whether the data support the hypothesis. In the case of Agent Orange, the data, that mice exposed to TCDD and 2,4,5-T had higher frequencies of cleft palate, matches the prediction. Additionally, veterans exposed to Agent Orange had higher rates of certain diseases, further supporting the hypothesis. We can thus accept the hypothesis that Agent Orange increases the incidence of birth defects and disease.

In practice, the scientific method is not as rigid and structured as it might first appear. Sometimes an experiment leads to conclusions that favor a change in approach; often, an experiment brings entirely new scientific questions to the puzzle. Many times, science does not operate in a linear fashion; instead, scientists continually draw inferences and make generalizations, finding patterns as their research proceeds (figure \(\PageIndex{g}\)). Even if the hypothesis was supported, scientists may still continue to test it in different ways. For example, scientists explore the impacts of Agent Orange, examining long-term health impacts as Vietnam veterans age.

Scientific findings can influence decision making. In response to evidence regarding the effect of Agent Orange on human health, compensation is now available for Vietnam veterans who were exposed to Agent Orange and develop certain diseases. The use of Agent Orange is also banned in the U.S. Finally, the U.S. has began cleaning sites in Vietnam that are still contaminated with TCDD.

Building on the Work of Others

Only rarely does a scientific discovery spring full-blown on the scene. When it does, it is likely to create a revolution in the way scientists perceive the world around them and to open up new areas of scientific investigation. Darwin's theory of evolution and Mendel's rules of inheritance are examples of such revolutionary developments. Most science, however, consists of adding another brick to an edifice that has been slowly and painstakingly constructed by prior work.

The development of a new technique often lays the foundation for rapid advances along many different scientific avenues. Just consider the advances in biology that discovery of the light microscope and, later, the electron microscope have made possible. Throughout these pages, there are many examples of experimental procedures. Each was developed to solve a particular problem. However, each was then taken up by workers in other laboratories and applied to their problems.

In a similar way, the creation of a new explanation (hypothesis) in a scientific field often stimulates workers in related fields to reexamine their own field in the light of the new ideas. Darwin's theory of evolution, for example, has had an enormous impact on virtually every subspecialty in biology as well as environmental science. To this very day, scientists in specialties as different as biochemistry and conservation biology are guided in their work by evolutionary theory (figure \(\PageIndex{g}\)).

References

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides. Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1994. 2, History of the Controversy Over the Use of Herbicides.

Neubert, D., Dillmann, I. Embryotoxic effects in mice treated with 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 272, 243–264 (1972).

Stellman, J. M., & Stellman, S. D. (2018). Agent Orange During the Vietnam War: The Lingering Issue of Its Civilian and Military Health Impact. American journal of public health, 108(6), 726–728.

Yi, S. W., Ohrr, H., Hong, J. S., & Yi, J. J. (2013). Agent Orange exposure and prevalence of self-reported diseases in Korean Vietnam veterans. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi, 46(5), 213–225.

Attributions

Modified by Melissa Ha from the following sources:

- The Process of Science from Environmental Biology by Matthew R. Fisher (licensed under CC-BY)

- Scientific Methods from Biology by John W. Kimball (licensed under CC-BY)