5.2.3: Symbiosis

- Page ID

- 37242

Learning Objectives

- Describe what is considered a symbiotic relationships between species

- Compare and contrast between commensalism, mutualism, and parasitism

- Describe symbiosis as it relates to nitrogen fixation

- Describe how saprophytes, epiphytes, and carnivorous plants depend on other orgnanisms

Symbiosis

Symbiotic relationships, or symbioses (plural), are close interactions between individuals of different species over an extended period of time which impact the abundance and distribution of the associating populations. Most scientists accept this definition, but some restrict the term to only those species that are mutualistic, where both individuals benefit from the interaction. In this discussion, the broader definition will be used.

Commensalism

A commensal relationship occurs when one species benefits from the close, prolonged interaction, while the other neither benefits nor is harmed. Birds nesting in trees provide an example of a commensal relationship (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The tree is not harmed by the presence of the nest among its branches. The nests are light and produce little strain on the structural integrity of the branch, and most of the leaves, which the tree uses to get energy by photosynthesis, are above the nest so they are unaffected. The bird, on the other hand, benefits greatly. If the bird had to nest in the open, its eggs and young would be vulnerable to predators. Another example of a commensal relationship is the clown fish and the sea anemone. The sea anemone is not harmed by the fish, and the fish benefits with protection from predators who would be stung upon nearing the sea anemone.

Mutualism

A second type of symbiotic relationship is called mutualism, where two species benefit from their interaction. Some scientists believe that these are the only true examples of symbiosis. Many animal pollinators have coevolved with plants, including many insects (bees, flies, butterflies, moths), birds (hummingbirds), and some mammals (bats). The pollinator usually receives a reward in the form of nectar or pollen, while the plant is able to distribute its pollen (which will produce the male gametes) to another plant. Flowers have evolved in response to natural selection to attract pollinators by scent, color, shape, phenology, and availability of the reward. Some plants are generalist and are pollinated by many different kinds of pollinators. Other plants are specialists and pollinated by only a few taxa, or perhaps even a single pollinator species (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Mycorrhizae: A Plant-Fungal Mutualism

One of the most remarkable associations between fungi and plants is the establishment of mycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza, which is derived from the Greek words myco meaning fungus and rhizo meaning root, refers to the fungal partner of a mutualistic association between vascular plant roots and their symbiotic fungi. Nearly 90 percent of all vascular plant species (and many nonvascular plant species) have mycorrhizal partners. In a mycorrhizal association, the fungal mycelia use their extensive network of hyphae and large surface area in contact with the soil to channel water and minerals from the soil into the plant. In exchange, the plant supplies the products of photosynthesis to fuel the metabolism of the fungus.

There are several basic types of mycorrhizae. Ectomycorrhizae (“outside” mycorrhizae) depend on fungi enveloping the roots in a sheath (called a mantle). Hyphae grow from the mantle into the root and envelope the outer layers of the root cells in a network of hyphae called a Hartig net Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). The fungal partner can belong to the Ascomycota, Basidiomycota or Zygomycota. Endomycorrhizae ("inside" mycorrhizae), also called arbuscular mycorrhizae, are produced when the fungi grow inside the root in a branched structure called an arbuscule (from the Latin for “little trees”). The fungal partners of endomycorrhizal associates all belong to the Glomeromycota. The fungal arbuscules penetrate root cells between the cell wall and the plasma membrane and are the site of the metabolic exchanges between the fungus and the host plant Figures \(\PageIndex{3b}\) and \(\PageIndex{4b}\). Orchids rely on a third type of mycorrhiza. Orchids are epiphytes that typically produce very small airborne seeds without much storage to sustain germination and growth. Their seeds will not germinate without a mycorrhizal partner (usually a Basidiomycete). After nutrients in the seed are depleted, fungal symbionts support the growth of the orchid by providing necessary carbohydrates and minerals. Some orchids continue to be mycorrhizal throughout their life cycle.

If symbiotic fungi were absent from the soil, what impact do you think this would have on plant growth?

Other examples of fungus–plant mutualism include the endophytes: fungi that live inside tissue without damaging the host plant. Endophytes release toxins that repel herbivores, or confer resistance to environmental stress factors, such as infection by microorganisms, drought, or heavy metals in soil.

Nitrogen Fixation: Root and Bacteria Interactions

Nitrogen is an important macronutrient because it is part of nucleic acids and proteins. Atmospheric nitrogen, which is the diatomic molecule \(\ce{N2}\), or dinitrogen, is the largest pool of nitrogen in terrestrial ecosystems. However, plants cannot take advantage of this nitrogen because they do not have the necessary enzymes to convert it into biologically useful forms. However, nitrogen can be “fixed,” which means that it can be converted to ammonia (\(\ce{NH3}\)) through biological, physical, or chemical processes. As you have learned, biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) is the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen (\(\ce{N2}\)) into ammonia (\(\ce{NH3}\)), exclusively carried out by prokaryotes such as soil bacteria or cyanobacteria. Biological processes contribute 65 percent of the nitrogen used in agriculture. The following equation represents the process:

\[\ce { N2 + 16 ATP + 8 e^{-} + 8 H^{+} \rightarrow 2 NH3 + 16 ADP + 16 P_i + H_2}\]

The most important source of BNF is the symbiotic interaction between soil bacteria and legume plants, including many crops important to humans (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). The NH3 resulting from fixation can be transported into plant tissue and incorporated into amino acids, which are then made into plant proteins. Some legume seeds, such as soybeans and peanuts, contain high levels of protein, and serve among the most important agricultural sources of protein in the world.

Farmers often rotate corn (a cereal crop) and soy beans (a legume), planting a field with each crop in alternate seasons. What advantage might this crop rotation confer?

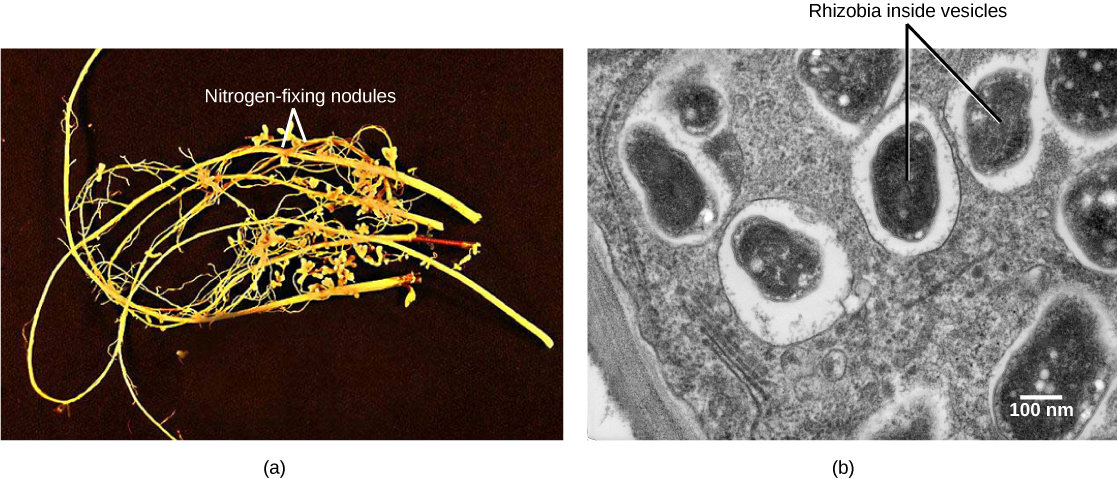

Soil bacteria, collectively called rhizobia, symbiotically interact with legume roots to form specialized structures called nodules, in which nitrogen fixation takes place. This process entails the reduction of atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia, by means of the enzyme nitrogenase. Therefore, using rhizobia is a natural and environmentally friendly way to fertilize plants, as opposed to chemical fertilization that uses a nonrenewable resource, such as natural gas. Through symbiotic nitrogen fixation, the plant benefits from using an endless source of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The process simultaneously contributes to soil fertility because the plant root system leaves behind some of the biologically available nitrogen. As in any symbiosis, both organisms benefit from the interaction: the plant obtains ammonia, and bacteria obtain carbon compounds generated through photosynthesis, as well as a protected niche in which to grow (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

Parasitism

A parasite is an organism that lives in or on another living organism and derives nutrients from it. In this relationship, the parasite benefits and the organism being fed upon (the host) is harmed. The host is usually weakened by the parasite as it siphons resources the host would normally use to maintain itself. The parasite, however, is unlikely to kill the host, especially not quickly, because this would not provide enough time for the organism to complete its reproductive cycle by spreading to another host. Dodder is an annual vine that grows parasitically on shrubs (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). Dodder has a weak, cylindrical stem that coils around the host and forms suckers. From these suckers, cells invade the host stem and grow to connect with the vascular bundles of the host. The parasitic plant obtains water and nutrients through these connections. The plant is a holoparasite because it is completely dependent on its host. Some parasitic plants, like leafy mistletoes, are fully photosynthetic and only use the host for water and minerals. These are considered hemiparasites. There are about 4,100 species of parasitic plants.

Heterotrophic Plants

Heterotrophic plants not have chlorophyll (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). Instead, they steal sugars from other plants, sometimes through a mycorrhizal fungus. These latter plants are called mycoheterotrophs.

Epiphytes

An epiphyte is a plant that grows on other plants, but is not dependent upon the other plant for nutrition (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). Epiphytes have two types of roots: clinging aerial roots, which absorb nutrients from humus that accumulates in the crevices of trees; and aerial roots, which absorb moisture from the atmosphere.

Insectivorous Plants

An insectivorous plant has specialized leaves to attract and digest insects. The Venus flytrap is popularly known for its insectivorous mode of nutrition, and has leaves that work as traps (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). The minerals it obtains from prey compensate for those lacking in the boggy (low pH) soil of its native North Carolina coastal plains. There are three sensitive hairs in the center of each half of each leaf. The edges of each leaf are covered with long spines. Nectar secreted by the plant attracts flies to the leaf. When a fly touches the sensory hairs, the leaf immediately closes. Next, fluids and enzymes break down the prey and minerals are absorbed by the leaf. Since this plant is popular in the horticultural trade, it is threatened in its original habitat.

Contributors and Attributions

Modified by Kammy Algiers and Melissa Ha from the following sources:

- Ecology of Fungi 24.3 and Nutritional Adaptations of Plants from Biology2e by OpenStax (licensed CC-BY)

Connie Rye (East Mississippi Community College), Robert Wise (University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh), Vladimir Jurukovski (Suffolk County Community College), Jean DeSaix (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Jung Choi (Georgia Institute of Technology), Yael Avissar (Rhode Island College) among other contributing authors. Original content by OpenStax (CC BY 4.0; Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72...f21b5eabd@9.87).